Wabanaki Confederacy facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Wabanaki Confederacy

Wabana'ki Mawuhkacik

|

|

|---|---|

| 1680s–1862 | |

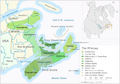

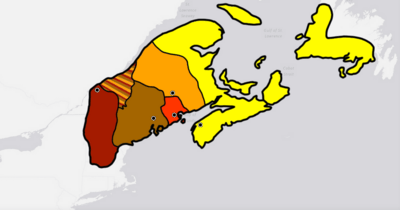

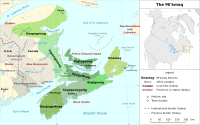

Yellow – Miꞌkmaꞌki, Orange – Wolastokuk, Red – Peskotomuhkatik, Brown – Pαnawαhpskewahki, Cayenne – Ndakinna

The dots are the listed capitals, being political centers in Wabanaki. The mixed region is territory outside of the historic ranges of the five tribes. It was acquired from the St.Lawrence Iroquois between 1541–1608 with Abenaki peoples having moved in by the time Samuel de Champlain came to the region establishing Quebec City. |

|

| Capital | Panawamskek, Odanak, Sipayik, Meductic, and Eelsetkook |

| Recognised regional languages | Abenaki Malecite-Passamaquoddy Mi'kmawi'simk English French |

| Religion | Traditional belief systems, including Midewiwin and Glooscap narratives; Christianity |

| Government | Confederation |

| History | |

|

• Established

|

1680s |

|

• Disestablished

|

1862 |

|

• Re-established

|

1993 |

| Today part of | Canada United States |

The Wabanaki Confederacy (also called Wabenaki or Wobanaki) was a group of Native American nations in North America. Their name means "People of the Dawn" or "Easterner." The Confederacy included four main Eastern Algonquian nations: the Miꞌkmaq, Maliseet (Wolastoqey), Passamaquoddy (Peskotomahkati), and Penobscot. The Western Abenaki were also part of this group. This included tribes like the Sokoki, Cowasuck, and Arsigantegok.

Many other tribes and smaller groups were once part of the Confederacy. Over time, some were absorbed into the five larger nations due to events like battles or tribes joining together.

Members of the Wabanaki Confederacy, known as the Wabanaki, lived in an area they called Wabanakik ("Dawnland"). This land was roughly the same as the French colony of Acadia. It covered most of present-day Maine in the United States. In Canada, it included New Brunswick, mainland Nova Scotia, Cape Breton Island, Prince Edward Island, and parts of Quebec south of the St. Lawrence River. The Western Abenaki lived in Quebec, Vermont, and New Hampshire.

Contents

- What does "Wabanaki" mean?

- Early European Encounters (1497-1680s)

- Forming the Wabanaki Confederacy (1680s)

- How the Wabanaki Confederacy was Governed

- Wabanaki Military and Conflicts

- British Rule and Changes

- Modern Revival of the Confederacy

- Wabanaki in Indigenous Languages

- Maps of Wabanaki Lands

- See also

What does "Wabanaki" mean?

The word Wabanaki comes from the Algonquian word "wab" and "aki" (meaning "land"). "Wab" is a root word used for several ideas:

| Algonquin word | English meaning |

|---|---|

| Wabi | He sees/sight |

| Waban | East |

| Wában | Sunlight |

| Wabish | White |

| Bidaban (Bid-waban) | Dawn |

| Wasseia | The light |

So, Waban-aki is most often translated as "Dawnland."

The Wabanaki Confederacy was known by many names, but "Wabanaki" is the most common. The "Abenaki" people share the same root word. All Abenaki are Wabanaki, but not all Wabanaki are Abenaki.

The Mi'kmaq, Passamaquoddy, and Wolastoqey called their political union Buduswagan, which means "convention council." The Passamaquoddy also had their own name, Tolakutinaya, meaning "be related to one another." The Penobscot called it Bezegowak ("those united into one") or Gizangowak ("completely united").

Early European Encounters (1497-1680s)

Before the Wabanaki Confederacy formed, smaller groups of tribes already existed. One early group was the Mawooshen Confederacy. Its main village, Kadesquit, near modern Bangor, Maine, became an important political center for the future Wabanaki Confederacy.

The first recorded meeting between Wabanaki people and Europeans was in 1497. An explorer named John Cabot landed in what is now Cape Breton. He took three Mi'kmaq people back to England. When he returned in 1498, the Mi'kmaq attacked his ships.

In 1500, Portuguese explorer Gaspar Corte-Real arrived. He captured and enslaved at least 57 people from Newfoundland and Nova Scotia. He sold them in Europe to pay for his trip. The rich fishing waters of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence attracted many Europeans. French fishermen began arriving around 1504. They also started kidnapping people, which hurt relations with some tribes. However, they also slowly introduced European goods to the Wabanaki.

In 1525, Portuguese explorer João Álvares Fagundes tried to start the first European colony in Wabanaki lands. He brought families from the Azores to Cape Breton. This fishing settlement lasted until at least 1570.

Throughout the 1500s, Wabanaki people met many European fishermen and explorers. They were often at risk of being captured and enslaved. For example, Estêvão Gomes kidnapped dozens of people in 1525. Giovanni da Verrazzano also captured a native boy around 1525.

Around 1534, French explorer Jacques Cartier explored the Gulf of Saint Lawrence. He traded with Mi'kmaq people and met the St. Lawrence Iroquoians. By the early 1600s, these Iroquoian villages were empty. Historians think they might have been defeated by the Mohawk people or other Algonquins.

Cartier brought back furs, especially beaver furs, which were very popular in Europe. This led to the North American fur trade. French traders like François Gravé Du Pont set up trading posts. In 1603, Samuel de Champlain joined one of these trips. His arrival marked a new era for Wabanaki and French relations.

In 1604, Champlain met the Mawooshen people on Pesamkuk (now Mount Desert Island, Maine). He noted they already had many European goods. Champlain had a good meeting with Sakom Asticou, a leader in the Mawooshen Confederacy. Champlain continued to set up settlements like Saint John (1604) and Quebec City (1608). The French and Wabanaki tribes had strong trade and military ties until the end of the French and Indian War.

In 1613, a Jesuit mission was approved by Asticou. However, English colonists led by John Smith destroyed it in 1614. Smith also tricked and enslaved 20 Algonquin people in Massachusetts.

English colonists also met the Mawooshen in 1605. Captain George Weymouth took five people captive to England. One of them, Sakom Tahánedo, later returned with settlers of the Popham Colony (1607-1608). However, local tribes were wary of the English colony.

Champlain built strong French ties with Algonquin tribes until his death in 1635. He fought against the Iroquois (likely Mohawk people) in battles like the Battle of Sorel in 1610. These battles led to poor French-Iroquois relations for many years.

More French traders arrived in Nova Scotia, forming settlements like Port-Royal. They traded weapons and other goods with the local Mi'kmaq. This made tribes more dependent on European goods. It also changed their traditional ways of life and led to competition for resources like beaver.

The Mi'kmaq, allied with the Maliseet and Passamaquoddy, fought with their Western neighbors (Western Abenaki/Penobscot) over trade goods. In 1615, the Mi'kmaq killed the Mawooshen Grand Chief Bashabas. This war was costly for all sides. A pandemic called "The Great Dying" (1616-1619) followed, killing 70-95% of the local Algonquin population.

After this population loss, Pilgrim settlers arrived in 1620. They began settling on ancestral Algonquin lands. Southern Abenaki people soon met English settlers moving into Massachusetts and southern Maine.

By the 1640s, internal conflicts made it hard for the Wabanaki and their allies to fight the Iroquois alone. With help from French Jesuits, a large Algonquian league formed against the Iroquois. By the 1660s, Western Abenaki tribes joined this league. This alliance helped repair relations among Eastern Algonquians and led to greater cooperation.

Growing tensions with the Iroquois and English colonists led to King Philip's War (1675-1676) and the First Abenaki War (1675-1678). After fighting together, many Algonquian tribes decided to form a stronger political union. This led to the Wabanaki Confederacy.

Forming the Wabanaki Confederacy (1680s)

The First Abenaki War showed native peoples in Eastern Algonquian lands that they faced a strong common enemy: the English colonists. The fighting caused many English settlements north of the Saco River in Maine to be abandoned. Wabanaki people south of the river were forced from their lands. The war ended with the Treaty of Casco. This treaty forced tribes to accept English property rights in southern Maine. In return, the English recognized Wabanaki independence. They agreed to pay Madockawando, a "grandchief" of the Wabanaki alliance, a small annual fee. They also recognized the Saco River as a border.

In the 1680s, Eastern Algonquians met at the Caughnawaga Council, a large neutral meeting place in Mohawk territory. With help from an Ottawa leader, they formed their own confederation. The Mawooshen Confederacy joined this larger group. In this new union, the tribes saw each other as family. This union helped them fight Iroquois attacks along the Saint Lawrence River. It also gave them political strength to push back against growing English expansion.

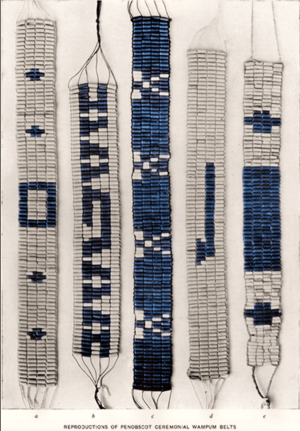

The new union borrowed ideas from other groups like the Iroquois and Huron. For example, they used wampum belts in their councils. This political group allowed people to travel safely through each other's lands. It also created safer trade routes and allowed tribes to share natural resources. People could move freely between villages, and inter-tribal marriages were common. It also formed a large defense alliance against attacks. For instance, Madockawando moved from Penobscot lands to Maliseet lands and lived in their political center, Meductic, until he died. These events led to the official creation of the Wabanaki Confederacy.

The Passamaquoddy wampum record, or Wapapi Akonutomakonol, tells how the Wabanaki Confederacy was formed at the Caughnawaga Council: "They sat silently for seven days. No one spoke. This was called, 'The Wigwam is Silent.' Every councilor thought about what to say when they made the laws. They all thought about how to stop the fighting. Then they opened the wigwam. It was called 'Every One of Them Talks.' And then they began their council... When everyone had finished talking, they decided to make a great fence. They put a great wigwam in the center of the fence. They also made a whip and gave it to their father. Whoever disobeyed him would be whipped. All his children inside the fence had to obey him. And he always had to keep their great fire burning. This is where the Wampum Laws came from. That fence was the confederacy agreement... There would be no arguing with each other again. They had to live like brothers and sisters from the same parent... And their parent was the great chief at Caughnawaga. The fence and the whip were the Wampum Laws. If anyone disobeyed them, the tribes together had to watch him."

How the Wabanaki Confederacy was Governed

The Wabanaki Confederacy was led by a council of elected leaders called sakoms. These leaders were often in charge of the villages along a river basin. Sakoms were respected listeners and debaters, not just rulers.

Wabanaki politics focused on reaching agreements after much discussion. Sakoms used special, symbolic language in their council meetings to persuade others. Older men who were good at debating were very influential. They were called nebáulinowak, or "riddle men."

Wabanaki sakoms held regular meetings at their "council fires," which were their centers of government. They would sit in a large rectangle, facing each other. Each sakom had a chance to speak and be heard, and they would listen to others. Each tribe also had a "kinship" status, like older or younger brothers. The Wabanaki government did not have one main capital city. This allowed leaders to move their influence to any part of the nation that needed it. When an agreement was reached, at least five representatives from different tribes would go to negotiate.

The Wabanaki started using wampum belts in their diplomacy during the 1600s. They learned this from their Huron allies and Iroquois enemies. Wampum belts, called gelusewa'ngan (meaning "speech"), were important for Wabanaki political meetings. Keepers of the wampum record were called putuwosuwin. They combined oral history with understanding the meaning of the wampum shells on the belts. "Wampum shells arranged on strings in such a way that certain combinations suggested certain sentences or ideas to the storyteller. The narrator knew the story by heart and was simply helped by the shells to remember parts of the tale." What was not recorded with wampum was remembered through a long chain of oral storytelling by village elders. Multiple elders could check each other's memories. For example, in a 1726 treaty, the Wabanaki challenged a claim that land was sold to English settlers, because no elder remembered it. Wabanaki leaders were very careful to ensure clear understanding of treaty terms. They discussed terms slowly, day by day, from August 1st to 5th. If they disagreed, leaders would talk among themselves before returning to debate.

The Wabanaki never had a single "grandchief" or one leader for the whole Confederacy. They also never had one main capital. Even though Madockawando was seen as a grandchief in one treaty, he and his descendants had the same power as any other sakom. This kept the Confederacy decentralized, so no one tribe had more power. This meant all big decisions were debated by sakoms at council fires. This created a strong political culture where the best debaters were powerful.

The tribes were not completely separate. They could place rules on each other for causing problems. Also, when a sakom died, new leaders were confirmed by other Wabanaki tribes. These tribes would visit after a year of mourning. An event to appoint a new sakom, called a Nská'wehadin or "assembly," could last for weeks. Tribes had a lot of freedom, but they worked together to maintain unity. This event continued until 1861, just before the Confederacy officially ended. Sometimes, sakoms ignored the will of the Confederacy, especially those on the borders with European powers. For example, Gray Lock, a successful Wabanaki war leader, refused to make peace after the 1722-1726 Dummer's War. This was because English colonists were settling his lands in Vermont. He fought a successful guerrilla war for two decades, stopping settlers from entering his lands.

Kinship terms like "Brother," "Father," or "Uncle" were very complex in their original languages. They showed the status and role of a diplomatic relationship. For example, the Penobscot were called ksés'i'zena or "our elder brother" by other Wabanaki tribes. The Passamaquoddy, Maliseet, and Mi'kmaq were called ndo'kani'mi'zena or "our younger brother." This system was not about one tribe being better, but about understanding relationships in a way that fit Wabanaki culture. An "older brother" might look out for the "younger brothers," who would respect the older brother's wisdom. This idea of being related helped create unity and cooperation, using family as a way to solve conflicts. The "age" rank was based on how close tribes were to the Caughnawaga Council.

When the Wabanaki called the French Canadian governor and the King of France "our father," it showed respect and a desire for protective care, like a Wabanaki father-son relationship. French and English diplomats often misunderstood this. They thought it meant the Wabanaki were admitting they were under French or English rule. This misunderstanding was a big challenge in diplomacy. Wabanaki culture and government always aimed for clear and mutual understanding in political matters.

The Wabanaki called the Ottawa "our father" because the Ottawa led the Caughnawaga Council and helped found the Wabanaki Confederacy. This did not mean the Wabanaki were under the Ottawa's rule. The Ottawa were seen as a neutral third party that helped maintain order.

Wabanaki Military and Conflicts

The Wabanaki Confederacy included:

- (Eastern) Abenaki or Panuwapskek (Penobscot)

- (Western) Abenaki

- Míkmaq (Miꞌkmaq, L'nu)

- Peskotomuhkati (Passamaquoddy)

- Wolastoqew, Wolastoq (Maliseet)

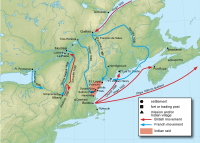

These nations also allied with the Innu of Nitassinan, the Algonquin people, and the Wyandot people. The Wabanaki homeland stretched from Newfoundland, Canada, to Massachusetts, United States. Members of the Wabanaki Confederacy fought in seven major wars:

- King Philip's War (1675–1678)

- King William's War (1688–1697)

- Queen Anne's War (1702–1713)

- Dummer's War (1722–1725)

- King George's War (1744–1748)

- Father Le Loutre's War (1749–1755)

- French and Indian War (1754–1763)

During this time, the Wabanaki population greatly decreased. This was due to many years of war, as well as famine and deadly infectious diseases like smallpox and measles brought by Europeans. Meanwhile, the number of European settlers grew from about 300 in 1650 to about 6,650 in 1750.

British Rule and Changes

The French were defeated by the British in 1753. The British government then treated Indigenous people poorly, especially the Mi'kmaq, who had supported the French. About 13,000 French settlers were forced out by the British. Their land was then settled by people from New England, Britain, and other European countries.

After 1783, when the American Revolutionary War ended, Black Loyalists were resettled in this area. These were freedmen (formerly enslaved people) from the British North American colonies. The British had promised them freedom if they left their Patriot masters and joined the British side. Three thousand freedmen were brought to Nova Scotia by British ships after the war.

Harsh policies by colonial and later federal governments against the Acadians, Black Canadians, and Mi'kmaq people often forced these groups to become allies. Some white and black parents even left their children on reserves to be raised in Wabanaki culture, as late as the 1970s. The colonial government officially disbanded the Wabanaki Confederacy in 1862. However, the five Wabanaki nations continued to exist and meet. The Confederacy was formally re-established in 1993.

Modern Revival of the Confederacy

The Wabanaki Confederacy gathering was brought back in 1993. The first meeting of the re-established Confederacy was suggested by Claude Aubin and Beaver Paul. It was hosted by the Mi'kmaq community of Listuguj. The sacred Council Fire was lit again, and its embers have been kept burning ever since. The revival brought together the Passamaquoddy Nation, Penobscot Nation, Maliseet Nation, Miꞌkmaq Nation, and Abenaki Nation.

After the 2010 Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), the member nations began to strongly assert their treaty rights. Wabanaki leaders stressed that the Confederacy continues to protect natural capital (natural resources).

There have been meetings with allies, like a "Water Convergence Ceremony" in May 2013, and meetings with Algonquin grandmothers in August 2013. Alma Brooks represented the Confederacy at the June 2014 UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues. She spoke about the Wabanaki/Wolostoq position on the Energy East pipeline. Opposition to this pipeline has helped organize the group: "On May 30 [2015], people from Saint John will join others in Atlantic Canada, including Indigenous people from the Wolastoqiyik (Maliseet), Passamaquoddy and Mi'kmaq, to march to the end of the proposed pipeline and draw a line in the sand." This event was widely shared.

2015 Grandmothers' Declaration

These meetings led to the Grandmothers' Declaration, adopted on August 21, 2015, in N'dakinna (Shelburne, Vermont). The Declaration included:

- Bringing back and keeping Indigenous languages alive.

- Article 25 of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples about land, food, and water.

- A promise to "establish decolonized maps."

- The Wingspread Statement on the Precautionary Principles (being careful about new technologies).

- The duty of governments to get "free, prior, and informed consent" before doing anything that affects Indigenous lands.

- A promise to "strive to unite the Indigenous Peoples; from coast to coast," for example, against Tar Sands.

- Protecting food, "seeds, waters, and lands, from chemical and genetic contamination."

- Recognizing the unique decision-making ways of the Wabanaki Peoples, as stated in Article 18 of the UN DRIP.

- "Our vision is to build a Lodge, which will be a living constitution and decision-making structure for the Wabanaki Confederacy."

- Recognizing the Western Abenaki living in Vermont and the United States as a "People" and member nation.

- Peace and friendship with "the Seven Nations of Iroquois."

2016 Conference

The Passamaquoddy Nation hosted the 2016 Wabanaki Confederacy Conference.

Wabanaki in Indigenous Languages

The term Wabanaki Confederacy in many Algonquian languages literally means "Dawn Land People."

| Language | "Easterner(s)" (literally "Dawn Person(s)") |

"Dawn Land" (nominative) |

"Dawn Land" (locative) |

"Dawn Land Person" | "Dawn Land People" or the "Wabanaki Confederacy" |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Naskapi | Waapinuuhch | ||||

| Massachusett language | Wôpanâ(ak) | ||||

| Quiripi language | Wampano(ak) | Wampanoki | |||

| Miꞌkmaq | Wapnaꞌk(ik) | Wapnaꞌk | Wapnaꞌkik | Wapnaꞌki | Wapnaꞌkiyik |

| Maliseet-Passamaquoddy | Waponu(wok) | Waponahk | Waponahkik | Waponahkew | Waponahkiyik/Waponahkewiyik |

| Abenaki-Penobscot | Wôbanu(ok) | Wôbanak | Wôbanakik | Wôbanaki | Wôbanakiak |

| Algonquin | Wàbano(wak) | Wàbanaki | Wàbanakìng | Wàbanakì | Wàbanakìk |

| Ojibwe | Waabano(wag) | Waabanaki | Waabanakiing | Waabanakii | Waabanakiig/Waabanakiiyag |

| Odawa | Waabno(wag) | Waabnaki | Waabnakiing | Waabnakii | Waabnakiig/Waabnakiiyag |

| Potawatomi | Wabno(weg) | Wabneki | Wabnekig | Wabneki | Wabnekiyeg |

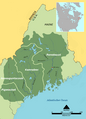

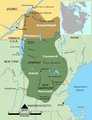

Maps of Wabanaki Lands

Here are maps showing the approximate locations of areas lived in by members of the Wabanaki Confederacy (from north to south):

-

Eastern Abenaki (Penobscot, Kennebec, Arosaguntacook, Pigwacket/Pequawket)

-

Western Abenaki (Arsigantegok, Missisquoi, Cowasuck, Sokoki, Pennacook)

See also

In Spanish: Confederación Wabanaki para niños

In Spanish: Confederación Wabanaki para niños