Ottawa dialect facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Ottawa |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nishnaabemwin, Daawaamwin | ||||

| Native to | Canada, United States | |||

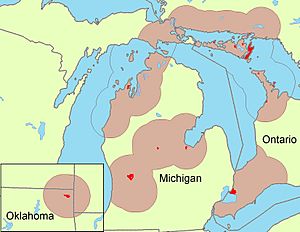

| Region | Ontario, Michigan, Oklahoma | |||

| Ethnicity | 60,000 Ottawa | |||

| Native speakers | Total: 1,135 US: 965 (2009-2013 language survey) Canada: 220 (2021 census) |

|||

| Language family |

Algic

|

|||

| Linguasphere | 62-ADA-dd (Odawa) | |||

Ottawa population areas in Ontario, Michigan and Oklahoma. Reserves/Reservations and communities shown in red.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

The Ottawa language, also known as Odawa, is a special way of speaking the Ojibwe language. It is spoken by the Ottawa people in southern Ontario, Canada, and northern Michigan, United States. Some Ottawa speakers also live in Kansas and Oklahoma.

Europeans first met Ottawa speakers in 1615. This happened when explorer Samuel de Champlain met a group of Ottawas on the north shore of Georgian Bay. The Ottawa language is written using Latin letters. Speakers call it Nishnaabemwin, which means 'speaking the native language', or Daawaamwin, meaning 'speaking Ottawa'.

Ottawa is one of the Ojibwe dialects that has changed a lot over time. One big change is that short vowel sounds often disappear in many words. This makes their pronunciation sound very different. These changes, along with differences in word structure and vocabulary, make Ottawa unique from other Ojibwe dialects.

Like other Ojibwe dialects, Ottawa grammar uses animate and inanimate (living or non-living) genders for nouns. It also has special verbs that depend on these genders. The language uses prefixes and suffixes (small parts added to the beginning or end of words) to change verb meanings. Ottawa also has a flexible word order, meaning words can be arranged in different ways in a sentence, unlike English which is more strict.

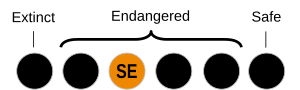

Many Ottawa speakers worry that their language is endangered. This is because more people are using English, and fewer people speak Ottawa fluently. To help save the language, there are Language revitalization efforts. These include second language learning classes in schools.

Contents

What is the Ottawa Language?

The Ottawa language is a dialect of the Ojibwe language. Speakers call it Nishnaabemwin, meaning 'speaking the native language'. This name comes from Anishinaabe 'native person'. Another name for the language is Daawaamwin, meaning 'speaking Ottawa'. The name of Canada's capital city, Ottawa, comes from the French word Outaouan, which came from the Ottawa people's own name for themselves, odaawaa.

The Ojibwe language family is part of the larger Algonquian language family. Ojibwe dialects are like a "dialect chain." This means that nearby dialects are easy to understand for speakers. But dialects that are far apart might be harder to understand. Ottawa is one of the dialects that has changed a lot. This makes it harder for Ottawa speakers to understand some other Ojibwe dialects.

Where is Ottawa Spoken?

The Ottawa language is mainly spoken in Ontario, Canada, and Michigan, United States. The map in the infobox shows the main areas where Ottawa people live.

Communities in Canada

Many Ottawa communities are in Ontario. Important places where the language is studied include Walpole Island in southwestern Ontario and Wikwemikong on Manitoulin Island in Lake Huron. Other communities are found along the north shore of Lake Huron, like Garden River and Thessalon. On Manitoulin Island, other communities include Sheshegwaning and West Bay.

Communities in the United States

In Michigan, Ottawa is spoken in places like Peshawbestown, Harbor Springs, and Mount Pleasant. Some Ottawa people moved to Kansas and Oklahoma. In 2006, only three older speakers were known in Oklahoma.

Number of Speakers

It is hard to know the exact number of Ottawa speakers. One report suggests about 8,000 speakers in the northern United States and southern Ontario. However, a study in the 1990s showed that fewer children are learning Ottawa as their first language. This means the number of fluent speakers is going down. Language classes are trying to help more people learn Ottawa as a second language.

How Ottawa Sounds

Ottawa has 17 consonants and 7 vowel sounds. The most special thing about Ottawa sounds is called vowel syncope. This means that short vowels often disappear when words are spoken.

This vowel disappearing act causes a few things:

- It makes Ottawa sound different from other Ojibwe dialects.

- It creates new groups of consonant sounds that are not found in other dialects.

- It changes how some words are pronounced.

Consonant Sounds

Ottawa consonants are divided into two groups: "strong" (fortis) and "weak" (lenis). Strong consonants are usually longer and voiceless (no vibration in the throat). Weak consonants are usually shorter and voiced (vibration in the throat).

Vowel Sounds

Ottawa has seven main vowel sounds. Four are long and three are short. Long vowels are written with double letters (like ii, oo, aa). Short vowels use single letters (like i, o, a). There is also a long vowel e that does not have a short partner. The difference between long and short vowels is very important in Ottawa. Only short vowels can disappear because of vowel syncope.

How Ottawa Grammar Works

Ottawa grammar is similar to other Ojibwe dialects. Words are grouped into categories like nouns, verbs, and pronouns.

Nouns in Ottawa are either animate (living things) or inanimate (non-living things). Verbs change based on the gender of the noun they are connected to. For example, a verb will look different if it's talking about an animate subject versus an inanimate one.

Word Structure (Morphology)

Ottawa words are built in complex ways. Small parts called prefixes (at the start of a word) and suffixes (at the end of a word) are added to word stems. These additions change the meaning of words.

For example, prefixes on verbs show who is doing the action (first person, second person, or third person). Suffixes on nouns can show if something is possessed, its location, or if it's small (diminutive).

One big change in Ottawa is how the person prefixes work. In other Ojibwe dialects, there's a prefix for 'his/her'. In Ottawa, this prefix is gone. So, jiimaan can mean 'a canoe' or 'his/her canoe'.

| English | Other Dialects | Ottawa |

|---|---|---|

| (a) first-person prefix | ni- | n- |

| (b) second person prefix | gi- | g- |

| (c) third-person | o- | — (no form) |

Sentence Structure (Syntax)

Ottawa sentences often start with a verb. Unlike English, which usually follows a subject-verb-object order, Ottawa has more freedom. The order of words can change to show what is most important in the sentence.

Ottawa uses different verb forms for different types of sentences. For example, there are special verb forms for main sentences, for parts of sentences that depend on another part, and for commands.

Ottawa also has a special way to talk about third persons (he, she, they). It uses "proximate" for the main third person in a story and "obviative" for a less important third person. This helps listeners know who is being talked about.

Ottawa Words

Most Ottawa words are not completely unique. This is because speakers of other Ojibwe dialects have moved into Ottawa areas. Words can easily spread between dialects. However, some groups of words are very special to Ottawa. These include words used to point things out (demonstrative pronouns) and question words (interrogative adverbs).

Pointing Words (Demonstrative Pronouns)

Ottawa has its own set of pointing words. For example, maaba 'this (animate)', gonda 'these (animate)', and nonda 'these (inanimate)' are only found in Ottawa.

| English | Wikwemikong | Curve Lake | Cape Croker |

|---|---|---|---|

| this (inanimate) | maanda | ow | maanda |

| that (inanimate) | iw, wi | iw | iw |

| these (inanimate) | nonda | now | now |

| those (inanimate) | niw | niw | niw |

| this (animate) | maaba | aw | maaba |

| that (animate) | aw, wa | aw | aw |

| these (animate) | gonda | gow | gow |

| those (animate) | giw | giw | giw |

Question Words (Interrogative Pronouns and Adverbs)

Ottawa question words often have the word -sh attached to them. This makes them a single word.

| English | Ottawa | Eastern Ojibwe |

|---|---|---|

| which | aanii-sh, aanii | aaniin |

| where | aanpii-sh, aapii, aapii-sh | aandi |

| who | wene-sh, wenen | wenen |

| how | aanii-sh, aanii | aaniin |

Other Special Ottawa Words

A few other words are very typical of Ottawa.

| English | Ottawa Terms | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| come here! | maajaan | — |

| father, my | noos | Also in some other dialects |

| mother, my | ngashi | — |

| pants | miiknod | Also in Algonquin |

| long ago | zhaazhi | — |

| necessarily | aabdig | Also in Eastern Ojibwe |

| be small (animate verb) | gaachiinyi | — |

How Ottawa is Written

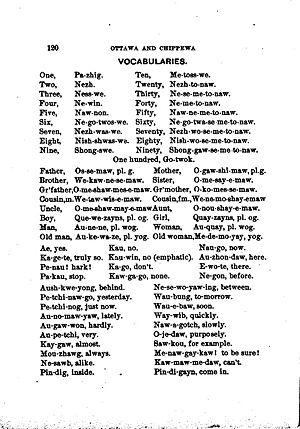

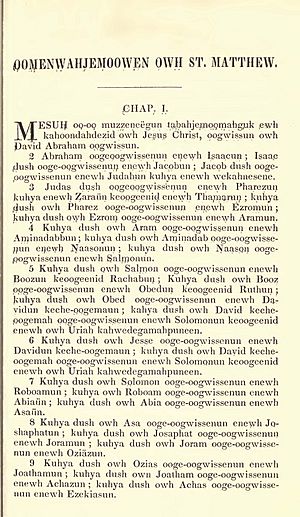

Europeans like explorers and missionaries first started writing Ottawa words. They used letters from their own languages, English and French. Ottawa people also wrote in their language, but not as often.

Today, many people are learning to read and write Ottawa in schools. There isn't one official way to write Ottawa, but a common system is used in dictionaries and grammar books. This system helps people learn and write the language in a consistent way.

Early Writing Methods

In the 1800s, missionaries like Frederic Baraga and Frederick O'Meara wrote in Ottawa. An Ottawa speaker named Andrew Blackbird also wrote a history of his people. It included details about the Ottawa language.

Ottawa speakers on Manitoulin Island also learned to write in their language. They used different writing styles depending on whether they learned from French Catholic or English Methodist missionaries. They wrote letters, petitions, and even articles for an Ojibwe newspaper.

Modern Writing System

The most common way to write Ottawa today is similar to a system used for other Ojibwe dialects. It is sometimes called the "Double Vowel system." This is because it uses two vowel letters (like ii or oo) for long vowel sounds.

This system uses letters from the English alphabet but gives them special Ottawa sounds. It focuses on the main sounds of the language, not every tiny detail of pronunciation. So, to speak Ottawa perfectly, you still need to listen to a fluent speaker.

The Ottawa writing system uses these consonant letters: b, ch, d, f, g, h, j, k, l, m, n, p, r, s, sh, t, w, y, z, zh

Letters like f, l, and r are mostly found in words borrowed from English, like telephonewayshin 'give me a call'.

The letter h is used for a special sound called a glottal stop. This is like the sound in the middle of "uh-oh."

Vowels are written like this: Long: ii, oo, aa, e Short: i, o, a

The apostrophe ’ is used to show when two consonants come together because a vowel has disappeared. For example, ng and n'g sound different.

History of the Language

The Ottawa language, like all languages, has changed over a long time. It comes from an older language called Proto-Algonquian. Over many years, Proto-Algonquian split into different dialects, and then these dialects changed into separate languages. Ojibwe is one of these languages, and Ottawa is one of its dialects. Ottawa, along with Severn Ojibwe and Algonquin, has changed the most over time.

Studying the Ottawa Language

The first European to write about meeting Ottawa speakers was Samuel de Champlain in 1615. French missionaries in the 1600s and 1700s also wrote down Ottawa words and grammar notes.

In the 1800s, Andrew Blackbird, an Ottawa speaker, wrote about his people and their language. Later, linguists (language scientists) like Leonard Bloomfield studied Ottawa in the 1930s and 1940s.

In the 1960s and 1970s, the Odawa Language Project at the University of Toronto did a lot of research. They studied Ottawa on Manitoulin Island. Linguists like Jonathan Kaye, Piggott, and Rhodes published many studies on Ottawa sounds and grammar. Valentine also wrote a detailed grammar book and a collection of Ottawa stories.

More recently, a book called Ottawa Stories from the Springs was published by Howard Webkamigad. This book translates old recordings of Ottawa stories from Northern Michigan. These recordings were made by Jane Willetts Ettawageshik between 1946 and 1949. They are very important because they were the first recordings of the Ottawa dialect in that area.

Sample Story

Traditional Ottawa stories are divided into two main types:

- aadsookaan: These are 'legends' or 'sacred stories'. They often feature mythical characters like the trickster Nenbozh.

- dbaajmowin: These are 'narratives' or 'stories' that don't always have mythical characters.

Here is a short story called Love Medicine, told by Ottawa speaker Andrew Medler to linguist Leonard Bloomfield in 1939.

Love Medicine

Andrew Medler

(1) Ngoding kiwenziinh ngii-noondwaaba a-dbaajmod wshkiniigkwen gii-ndodmaagod iw wiikwebjigan.

- 'Once I heard an old man tell of how a young woman asked him for love medicine.'

(2) Wgii-msawenmaan niw wshkinwen.

- 'She was in love with a young man.'

(3) Mii dash niw kiwenziinyan gii-ndodmawaad iw wiikwebjigan, gye go wgii-dbahmawaan.

- 'So then she asked that old man for the love medicine, and she paid him for it.'

(4) Mii dash gii-aabjitood maaba wshkiniigkwe iw mshkiki gaa-giishpnadood.

- 'Then this young woman used that medicine that she had bought.'

(5) Mii dash maaba wshkinwe gaa-zhi-gchi-zaaghaad niw wshkiniigkwen.

- 'Then this young man accordingly very much loved that young woman.'

(6) Gye go mii gii-wiidgemaad, gye go mii wiiba gii-yaawaawaad binoojiinyan.

- 'Then he married her; very soon they had children.'

(7) Aapji go gii-zaaghidwag gye go gii-maajiishkaawag.

- 'They loved each other and they fared very well.'

See also

Images for kids

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |