John Cabot facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

John Cabot

|

|

|---|---|

| Giovanni Caboto | |

John Cabot in traditional Venetian garb – mural painting by Giustino Menescardi (1762), in the Sala dello Scudo in the Doge's Palace, Venice

|

|

| Born | c. 1450 Gaeta or Castiglione Chiavarese

|

| Died | c. 1499 |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Other names | Giovanni Caboto, Zuan Chabotto, Giovanni Chabotte, Juan Caboto, Jean Caboto |

| Occupation | Maritime explorer |

| Known for | First European since the Norse colonization of North America to explore coastal parts of North America |

| Spouse(s) | Mattea (m. circa 1470) |

| Children | Ludovico, Sebastian, and Sancto |

| Relatives | Catalina de Medrano (daughter-in-law) |

John Cabot (born around 1450, died around 1499) was an Italian navigator and explorer. He is famous for his 1497 voyage to the coast of North America. This journey was made under the command of King Henry VII of England. It was the first known European exploration of coastal North America since the Norse people visited in the 11th century.

To celebrate the 500th anniversary of Cabot's trip, both the Canadian and British governments named Cape Bonavista, Newfoundland, as his first landing spot. However, other places have also been suggested as his landing site.

Contents

Who Was John Cabot?

John Cabot is known by several names today. In Italian, he is Giovanni Caboto. In Venetian, he is Zuan Caboto. In French, he is Jean Cabot, and in English, John Cabot. This happened because people often changed names to fit local languages in documents. Cabot himself signed his name "Zuan Chabotto" in Venice.

His last name, Cabot, comes from a Latin word meaning "head." It might have been a nickname that became a family name.

Cabot was born in Italy. His parents were Giulio Caboto and his wife. He also had a brother named Piero. Historians believe he was born in either Gaeta or Castiglione Chiavarese. Records show a Caboto family in Gaeta until the mid-1400s.

Pedro de Ayala, a Spanish ambassador in London, described Cabot as "another Genoese like Columbus." John Cabot's son, Sebastian, also said his father was from Genoa. Cabot became a citizen of the Republic of Venice in 1476. To become a citizen, he had to live in Venice for at least 15 years. This means he likely lived there from about 1461.

Early Life and Venetian Roots

Cabot might have been born a little earlier than 1450, which is the most common guess for his birth year. In 1471, he joined a religious group called the confraternity of the Scuola Grande di San Giovanni Evangelista. This was a respected group in Venice. Joining it showed that he was already an important person in the community.

After becoming a full Venetian citizen in 1476, Cabot could take part in sea trade. This included trade with the eastern Mediterranean Sea, which made Venice very rich. He likely started trading soon after. He probably learned a lot about spices and silks from the East during this time.

Venetian records from the late 1480s mention "Zuan Cabotto." These records show that by 1484, he was married to Mattea and had several sons. His sons were Ludovico, Sebastian, and Sancto.

Seeking Support for Exploration

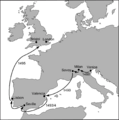

Cabot looked for money and royal support in England. He wanted to sail west from a northern area. His goal was to find a northern route to Asia.

Historians once thought Cabot went straight to Bristol when he arrived in England. Bristol was a major port city. It had a history of sending ships to explore the Atlantic. Cabot's royal permission, given in 1496, said all trips must start from Bristol. This suggests his main financial helpers were in that city. The king also said that any goods found must only be brought to England through Bristol. The king would receive one-fifth of the profits. This made Bristol a special port for trade.

More recent research by historian Alwyn Ruddock found that Cabot first went to London. There, he received some money from the Italian community. One supporter was Father Giovanni Antonio de Carbonariis, a friar. He was also a tax collector for the Pope. Ruddock believed Carbonariis introduced Cabot to King Henry VII. She also suggested that Cabot got a loan from an Italian bank in London. Later research confirmed that Cabot received money in March 1496 from the Bardi family bank in Florence. This money helped support his trip to "find the new land."

The King's Royal Permission

On March 5, 1496, King Henry VII gave Cabot and his three sons special permission. This permission, called letters patent, allowed them to explore:

... free authority, faculty and power to sail to all parts, regions, and coasts of the eastern, western and northern sea, under our banners, flags, and ensigns, with five ships or vessels of whatsoever burden and quality they may be, and with so many and with such mariners and men as they may wish to take with them in the said ships, at their own proper costs and charges, to find, discover and investigate whatsoever islands, countries, regions or provinces of people who were not Christian, in whatsoever part of the world placed, which before this time were unknown to all Christians.

This meant they could sail anywhere in the east, west, and north seas. They could use up to five ships and take as many sailors as they wanted. Their goal was to find new islands, countries, or regions unknown to Christians. Cabot's sons were likely still young at this time.

Cabot's Exciting Expeditions

Cabot went to Bristol to get ready for his voyage. Bristol was England's second-largest seaport. For many years, ships from Bristol had searched for the mythical island of Hy-Brasil. According to Celtic stories, this island was somewhere in the Atlantic Ocean.

Merchants in Bristol widely believed that their sailors had found this island before. They thought they had then lost track of it. The island was believed to have brazilwood, which made a valuable red dye. This gave merchants a strong reason to find it.

The First Attempt (1496)

Not much is known about Cabot's first voyage. A letter from John Day, a Bristol merchant, mentions this trip briefly. He wrote that Cabot went with one ship. The crew became confused, they ran out of supplies, and bad weather hit them. Because of these problems, Cabot decided to turn back. Since he received his royal permission in March 1496, this first trip likely happened that summer.

The Famous Second Voyage (1497)

Preparing for the Journey

Most of what we know about the 1497 voyage comes from four short letters. There is also an entry in a 1565 record book from the city of Bristol. This record says:

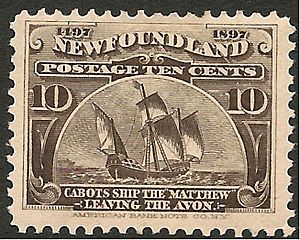

This year, on St. John the Baptist's Day [June 24, 1497], the land of America was found by the Merchants of Bristow in a shippe of Bristowe, called the Mathew; the which said ship departed from the port of Bristowe, the second day of May, and came home again the 6th of August next following.

The John Day letter from late 1497 or early 1498 gives more details. Day likely knew the people involved in the expedition.

Cabot's ship was described as a "little ship" of 50 tons. It was called the Matthew of Bristol. The ship carried enough supplies for "seven or eight months." It left in May with a crew of 18 to 20 men. Among them were a man from Burgundy (now the Netherlands) and a barber surgeon from Genoa. Barbers at that time also performed minor medical procedures.

Two important Bristol merchants were likely part of the trip. One was William Weston. A document found recently shows that King Henry VII ordered a pause in legal action against Weston. This was because the King wanted Weston to soon make a voyage to the "new founde land." This was probably the trip under Cabot's permission. This would make William Weston the first Englishman to lead an expedition to North America. Weston and Cabot received rewards from the king in January 1498. This suggests they worked together before the second voyage.

Where Did He Land?

Leaving Bristol, the expedition sailed past Ireland and across the Atlantic Ocean. They landed somewhere on the coast of North America on June 24, 1497. The exact landing spot has been debated for a long time. Many communities want the honor of being the first landing site. Historians have suggested Cape Bonavista and St. John's, Newfoundland; Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia; Labrador; and Maine. After the John Day letter was found in the 1950s, it seems most likely the first landing was on Newfoundland or nearby Cape Breton Island.

For the 500th-anniversary celebrations, the governments of Canada and the United Kingdom officially named Cape Bonavista in Newfoundland as the landing place. In 1997, Queen Elizabeth II and officials from Italy and Canada greeted a replica of the Matthew there.

Cabot reportedly landed only once during this trip. He did not go "beyond the shooting distance of a crossbow." Reports say the crew did not meet any native people. However, they found signs of human presence, like a fire, a human trail, nets, and a wooden tool. The crew seemed to stay on land just long enough to get fresh water. They also raised the Venetian and Papal flags. This claimed the land for the King of England and recognized the Roman Catholic Church's authority. After this landing, Cabot spent weeks "discovering the coast."

Celebrating a Discovery

When Cabot returned to Bristol, he traveled to London to report to the king. On August 10, 1497, he received a reward of £10. This was a large sum, equal to about two years' pay for a regular worker.

Cabot was celebrated. One writer noted that, like Christopher Columbus, Cabot "is called the Great Admiral." He received great honor and wore silk clothes. People in England "ran after him like mad." This excitement did not last long. The king's attention soon turned to a rebellion in Cornwall.

Once the king's power was secure, he thought more about Cabot. On September 26, the king gave Cabot another £2. On December 13, 1497, the explorer was given a yearly payment of £20. This money came from customs taxes collected in Bristol. The payment was backdated to March 1497. This showed that Cabot was working for the king during his expedition. Despite the king's order, Bristol's tax officers first refused to pay Cabot. He had to get another order from the king. On February 3, 1498, Cabot received new permission for another voyage. This helped him prepare a new expedition.

In March and April, the king also loaned money to Lancelot Thirkill, Thomas Bradley, and John Cair. These men were to join Cabot's new expedition.

The Mysterious Final Voyage (1498)

The Great Chronicle of London reports that Cabot left Bristol with five ships in early May 1498. One of these ships was prepared by the king. Some ships were said to carry goods like cloth and caps. This suggests Cabot planned to trade on this trip. The Spanish ambassador in London reported in July that one ship was caught in a storm and landed in Ireland. However, Cabot and the other four ships continued their journey.

For many years, no other records about this expedition were found. It was believed that Cabot and his fleet were lost at sea. However, at least one man who was supposed to go on the trip, Lancelot Thirkill, was recorded as living in London in 1501.

It is still unknown what happened to John Cabot. He might have died during the voyage. He might have returned safely and died soon after. Or, he might have reached the Americas and chosen to stay there.

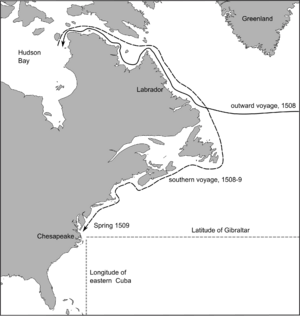

Historian Alwyn Ruddock believed that Cabot and his expedition returned to England in the spring of 1500. She thought they had explored the east coast of North America for two years. This exploration might have reached as far south as the Chesapeake Bay area. It might even have reached Spanish lands in the Caribbean. Her evidence included a world map by Spanish mapmaker Juan de la Cosa. This map showed the North American coast and seas "discovered by the English" between 1497 and 1500.

The Cabot Project at the University of Bristol was started in 2009. Researchers there are looking for evidence to support Ruddock's claims. They have found more evidence that suggests John Cabot was in London by May 1500. However, this information has not yet been fully published.

The project is also working on an archaeological dig in Carbonear, Newfoundland. This is believed to be a possible location for a mission settlement. The dig has found evidence of people living there since the late 1600s. They also found signs of trade with Spain.

Other English Explorations

Historian Ruddock also claimed that William Weston of Bristol made his own trip to North America in 1499. She believed he sailed north from Newfoundland up to the Hudson Strait. If true, this would have been the first search for the Northwest Passage. In 2009, Evan Jones confirmed that William Weston led an expedition from Bristol to the "new found land" in 1499 or 1500. This makes him the first Englishman to lead exploration in North America. This discovery has changed how we understand England's role in exploring the continent. In 2018, it was revealed that Weston received £30 from the King in 1500 for "his expenses about the finding of the new land."

King Henry VII continued to support exploration from Bristol. He gave money to other explorers for new voyages. Around this time, Bristol explorers formed a company called the Company Adventurers to the New Found Land. This company made more trips in 1503 and 1504.

In 1508–09, Sebastian Cabot made a final voyage to North America from Bristol. According to Peter Martyr's account, this trip explored the coast from Hudson Bay to about Chesapeake Bay. After returning to England in 1509, Sebastian found that King Henry VII had died. The new king, Henry VIII, was not very interested in westward exploration.

John Cabot's Family

John Cabot married Mattea around 1470. They had three sons:

- Ludovico Caboto

- Sebastiano Caboto

- Santo Caboto

Sebastian Cabot's Own Adventures

Sebastian Cabot, one of John's sons, also became an explorer. He made at least one voyage to North America. In 1508, he was looking for the Northwest Passage. Nearly 20 years later, he sailed to South America for Spain. He hoped to repeat Ferdinand Magellan's trip around the world. However, he became sidetracked by searching for silver along the Río de la Plata in Argentina from 1525 to 1528.

Remembering John Cabot

is at Bristol's City Hall]].

John Cabot is remembered in many ways:

- Cabot Tower (1897) in St. John's, Newfoundland and Labrador. It was built to mark the 400th anniversary of Cabot's voyage.

- Cabot Tower, in Bristol, England. This 30-meter-tall red sandstone tower was started in 1897 for the 400th anniversary.

- Denis William Eden painting: John Cabot and his sons receive the charter from Henry VII to sail in search of new lands (1910), at the Houses of Parliament.

- Giovanni Caboto Club (established 1925), an Italian club in Windsor, Ontario.

- John Cabot University is a United States-affiliated university established in 1972 in Rome, Italy.

- A 1985 bronze statue of the explorer by Stephen Joyce, is located at Bristol Harbourside.

- A replica of the Matthew of Bristol was built to celebrate the 500th anniversary of the 1497 voyage. It is docked in Bristol.

- A second replica of the Matthew is located at Cape Bonavista.

- The beautiful Cabot Trail in the Cape Breton Highlands is named after the explorer.

- John Cabot Academy is a school in Bristol, England.

- Cabot Ward was an election area in Bristol (ended in 2016), named after the local Cabot Tower.

- Cabot Squares in London and Montreal.

- Cabot Circus, a shopping mall in Bristol opened in 2008, named after a citywide poll.

- Cabot Street and Cabot Avenue in St. John's, Newfoundland and Labrador.

- A bronze statue of the explorer stands at the Confederation Building, St. John's.

- A bronze statue of the explorer is located at Cape Bonavista, Newfoundland. Plaques in English, French, and Italian remember the historic voyage.

- John Cabot Catholic Secondary School in Mississauga, Ontario, is named after the explorer.

- Giovanni Caboto park located in Edmonton, Alberta.

- The Cabot Institute for the Environment at the University of Bristol is named after him.

- In 1897, the Newfoundland Colony issued a postage stamp. In 1947, the Dominion of Newfoundland issued another stamp. These marked the 400th and 450th anniversaries of Cabot's voyage.

- The United States Navy named two ships USS Cabot. One was a 14-gun brig in 1775. The other was a light aircraft carrier in 1943. Also, the aircraft carrier USS Lexington (CV-16), launched in 1942, was first planned to be named Cabot.

Interesting Facts About John Cabot

- John Cabot is known by different names in different languages. In Italian, he is Giovanni Caboto. In French, he is Jean Cabot. This was common back then, as people often changed names to fit their local language.

- He might have been born a little earlier than 1450, which is the most common guess for his birth year.

- Historian Alwyn Ruddock believed that Cabot and his expedition returned to England in the spring of 1500. She thought they had explored the east coast of North America for two years, going as far south as the Chesapeake Bay area and maybe even to Spanish lands in the Caribbean.

- Sebastian Cabot, one of John's sons, also became an explorer. He later made at least one trip to North America.

- The United States Navy named two ships after him: the USS Cabot, a 14-gun brig in 1775, and the USS Cabot, a light aircraft carrier in 1943.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Juan Caboto para niños

In Spanish: Juan Caboto para niños

- List of people who disappeared mysteriously at sea