Naskapi facts for kids

| Flag of the Kawawachikamach Band of the Naskapi Nation | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 1,080 (2016 census) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Canada (Quebec and Newfoundland and Labrador) | |

| Languages | |

| Naskapi, English, French | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity, other | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Innu, Cree |

The Naskapi people are an Indigenous group who have lived for a long time in northern Quebec and Labrador, Canada. Their traditional land is called St'aschinuw (ᒋᑦ ᐊᔅᒋᓄᐤ), which means 'our land'. They are closely related to the Innu Nation, another Indigenous group in Canada.

The Innu people are often seen as two main groups. One group, called the Neenoilno (or Montagnais by French people), lives along the north shore of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence. The Naskapi live farther north and are fewer in number. The Innu themselves have different names for groups based on where they live and the dialects of their language.

The name "Naskapi" means "people beyond the horizon." It first appeared in the 1600s. This name was given to Innu groups who lived far away from missionaries, especially those near Ungava Bay and the northern Labrador coast. The Naskapi traditionally moved around a lot, following animals and seasons. This is different from the Montagnais, who tended to stay in one area. The Naskapi language and culture are quite different from the Montagnais. For example, a word might change from "Iiyuu" to "Innu" depending on the dialect. Some Naskapi families from Kawawachikamach have relatives in the Cree village of Whapmagoostui on the eastern shore of Hudson Bay.

Contents

Naskapi History

Early European Contact

The first mention of the Naskapi in writing was around 1643. A Jesuit missionary named André Richard wrote about the "Ounackkapiouek." Not much is known about this group, except that they were one of many "small nations" north of Tadoussac. The word "Naskapi" was first used in 1733. At that time, about 40 families were described as Naskapi, with a main camp at Lake Achouanipi.

Around the same time, in 1740, Joseph Isbister from the Hudson's Bay Company heard about Indigenous people called "Annes-carps" living northeast of Richmond Gulf. Later, these people were called "Nascopie" or "Nascappe." In 1790, missionaries described a group of Indigenous people living west of Okak as "Nascopies." The Naskapi became influenced by Protestant missionaries and are still Protestant today. They speak English in addition to their native language. Their Montagnais relatives are mostly Roman Catholic and speak French.

Regular contact between the Naskapi and European society began in 1831. This was when the Hudson's Bay Company opened its first trading post at Old Fort Chimo.

The Naskapi's relationship with the Hudson's Bay Company was not easy. It was hard for the Naskapi to fit commercial trapping into their traditional way of life. Trapping animals like marten often meant going to areas where their usual food sources were not available. Because of this, the Naskapi were not always the regular trappers the company hoped for. The traders sometimes thought this was due to laziness.

In 1945, a census in Labrador counted 270 Innu people (both Montagnais and Naskapi). This number has grown to over 2,000 today. Before 1949, most Innu in Labrador did not have last names. They lived in tents near Inuit settlements during the summer.

Forced Moves and Challenges

Between 1831 and 1956, the Naskapi were forced to move many times. These moves were usually for the Hudson's Bay Company's business needs, not for the Naskapi's well-being. Major moves included:

- 1842 – From Fort Chimo to Fort Nascopie

- 1870 – From Fort Nascopie to Fort Chimo

- 1915 – From Fort Chimo to Fort McKenzie

- 1948 – From Fort McKenzie to Fort Chimo

- 1956 – From Fort Chimo to Schefferville

The Hudson's Bay Company often moved the Naskapi without caring if the new areas had enough fish and game for them to eat. In some cases, managers even refused to give the Naskapi ammunition for hunting food. This led to many Naskapi suffering greatly from lack of food.

By the late 1940s, the Naskapi faced many challenges. The fur trade, diseases from Europeans, and the near disappearance of the George River Caribou Herd threatened their survival.

The Canadian government started providing "relief" to the Naskapi in 1949. Officials visited them in Fort Chimo and arranged for welfare payments.

In the early 1950s, the Naskapi tried to move back to Fort McKenzie. They wanted to return to a life based on hunting, fishing, and trapping. However, they could no longer be fully self-sufficient. The high cost of supplying them and ongoing health issues like tuberculosis forced them back to Fort Chimo after only two years.

Moving to Schefferville

In 1956, almost all Naskapi moved from Fort Chimo to Schefferville, a new iron-ore mining town. It's not fully clear why they moved. Some believe government officials told them to move. Others think the Naskapi hoped to find jobs, housing, medical care, and schools for their children there.

Government officials knew the Naskapi planned to move but did little to prepare for their arrival. They didn't even warn the mining company or the town of Schefferville.

The Naskapi walked about 400 miles (640 km) from Fort Chimo to Schefferville. By the time they reached Wakuach Lake, about 70 miles (110 km) north of Schefferville, many were exhausted, sick, and close to starvation.

A rescue effort helped them, but the Naskapi only had shacks they built themselves near Pearce Lake. In 1957, the town moved them to a site near John Lake, about four miles (6 km) north of Schefferville. Here, they had no running water, sewage, or electricity. There was also no school for their children or medical facility, despite their hopes.

The Naskapi shared the John Lake site with a group of Montagnais. These Montagnais had moved voluntarily from Sept-Îles to Schefferville earlier.

At first, the Naskapi lived in small shacks. But by 1962, the government built 30 houses for them.

Moving to Matimekosh

In 1969, the government bought a marshy, 39-acre (15.8 ha) site north of Schefferville, next to Pearce Lake. By 1972, 43 row houses were built there for the Naskapi and 63 for the Montagnais. Most Naskapi and Montagnais moved to this new site, now called Matimekosh.

For the first time, the Naskapi were asked for their ideas when planning their new home. Government officials explained the new community, published a brochure, and built models. The Naskapi were very interested in the type of housing. The government wanted them to live in row houses, but the Naskapi preferred separate, single-family homes. The Naskapi Council agreed to row houses only if they were soundproofed, which they were not.

The Naskapi had trusted the government's promises during this planning. Even today, many Naskapi feel that not all promises were kept. For example, the row houses were not soundproofed and had other problems. Also, the brochure showed a landscaped site with trees, but no landscaping was ever done.

These incidents, though seemingly small, were very important to the Naskapi. They were still learning to deal with large government groups and remembered the harsh treatment from the Hudson's Bay Company. These events are still talked about today and hold great meaning for many Naskapi.

James Bay Agreement

A very important event for the Naskapi happened in 1975. After visits from leaders of the Grand Council of the Crees and the Northern Quebec Inuit Association, the Naskapi decided to join talks for the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement (JBNQA).

The Naskapi first worked with the Inuit group for support and legal advice. However, this arrangement didn't work well, and the JBNQA was signed in November 1975 without the Naskapi.

Soon after, the Naskapi realized the Inuit group had too much to do. So, the Naskapi hired their own advisors and started negotiating on their own.

The people who signed the JBNQA knew that it would end the Naskapi's Aboriginal rights in the area without giving them anything in return. They also knew the Naskapi wanted to negotiate their own agreement.

So, in 1977, the parties to the JBNQA agreed to negotiate with the Naskapi. This led to the Northeastern Quebec Agreement (NEQA), signed on January 31, 1978. This agreement was similar to the JBNQA.

Section 20 of the NEQA gave the Naskapi the chance to move from the Matimekosh Reserve to a new location.

Moving to Kawawachikamach

Between 1978 and 1980, studies were done to find the best place for a new Naskapi community. On January 31, 1980, the Naskapi voted to move to the current site of Kawawachikamach. This community was built mostly by Naskapi people between 1980 and 1983. This building project helped Naskapi gain skills in administration, construction, and maintenance.

From 1981 to 1984, the Naskapi negotiated with Canada for self-government laws, as promised in the NEQA. This resulted in the Cree-Naskapi (of Quebec) Act (CNQA), passed by Parliament in 1984.

The main goal of the CNQA was to give the Naskapi Nation of Kawawachikamach (NNK) and the James Bay Cree Bands more control over their own affairs. Many powers that the government used to have over Indigenous communities were transferred to the Naskapi and Cree elected councils. They also gained powers similar to those of other towns in Canada.

The NEQA was planned assuming that Schefferville would continue to be a busy mining town. However, in 1982, the Iron Ore Company of Canada announced it would close the mines in Schefferville immediately.

The closing of the mines had a big impact on the NEQA. It affected plans for health services, training, and jobs. So, in the late 1980s, the NNK and the Canadian government reviewed how Canada was meeting its responsibilities under the NEQA. This review was mainly because of the changes in Schefferville and for the Naskapi people.

Northeastern Quebec Agreement Implementation

These discussions led to the Agreement Respecting the Implementation of the Northeastern Quebec Agreement (ARINEQA), signed in September 1990. This agreement set up how funding for buildings and operations would work for five-year periods. It also created a way to solve disagreements about the NEQA and other agreements. Plus, it formed a group to help Naskapi find jobs.

Naskapi Today: Economy and Community

The Naskapi people are now working to develop their homeland. They focus on growing their economy and strengthening their community.

Here are some of their economic projects:

- Schefferville Airport Corporation: They help maintain the airport runway.

- James Bay TransTaiga Road Maintenance: They help maintain this important road.

- Naskapi Typonomy Project: This project deals with place names.

- Menihek Power Dam and Facilities: They are involved with this power project.

- Enterprise, Resource, Planning, and Management Software: They have their own software company.

They are also developing these areas:

- Commercializing Caribou: They have a company that sells caribou meat.

- Caribou Hunting and Fishing Operations: They manage hunting and fishing clubs.

Naskapi First Nations Communities

Naskapi Nation of Kawawachikamach

The Naskapi Nation of Kawawachikamach is a First Nation with about 850 registered members. Most of them live in Kawawachikamach, Quebec, which is about 16 km (10 miles) northeast of Schefferville. The village covers about 40 acres (16 hectares) and is located on 16 square miles (41 km²) of special land set aside for them. There is plenty of space for the community to grow.

Most people in Kawawachikamach are Naskapi. Their main language is Naskapi, spoken by everyone and written by many. English is their second language, and many young people also speak some French. The Naskapi still keep many parts of their traditional way of life and culture. Like many northern communities, the Naskapi rely on hunting, fishing, and trapping for much of their food and materials. Harvesting is a very important part of Naskapi spirituality.

Kawawachikamach is connected to Schefferville by a gravel road that can be used all year. A train runs weekly between Schefferville, Wabush, Labrador City, and Sept-Îles. The train carries passengers and goods, including large vehicles and fuel. Schefferville has a paved airport runway and year-round flight service five days a week.

Mushuau Innu First Nation

The Mushuau Innu First Nation is located in Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada. In 1967, the Mushuau Innu were settled in Utshimassits (Davis Inlet) on Iluikoyak Island. This made it hard for them to continue their traditional caribou hunt on the mainland. Because of this, they were moved in 2002-2003 to their new main settlement, Natuashish. Natuashish is about 295 km (183 miles) north of Happy Valley-Goose Bay and 80 km (50 miles) southeast of Nain. It is on the mainland, only 15 km (9 miles) west of Utshimassits.

The Mushuau Innu are ethnically Naskapi. They speak the Eastern Dialect of Iyuw Imuun. Most of the tribe is Catholic and uses the Latin alphabet for writing. Their reserve is called Natuashish #2 and covers about 44 km² (17 square miles). The population is 936 people.

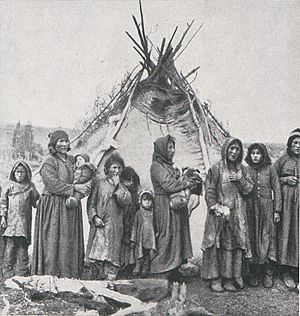

Images for kids