Raid on Grand Pré facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Raid on Grand Pré |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Queen Anne's War | |||||||

Colonel Benjamin Church, the "Father of American ranging" |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Acadia Mi'kmaq Indians |

|||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Unknown | Benjamin Church John Gorham (Grandfather of John Gorham) Winthrop Hilton Cyprian Southack |

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Unknown | 500 volunteers and warriors | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| About 6 killed, unknown wounded 45 captured |

6 killed, unknown wounded | ||||||

The Raid on Grand Pré was a major attack led by Colonel Benjamin Church from New England. It happened in June 1704, during a conflict known as Queen Anne's War. This attack was a response to a previous raid by French and Native American forces on the Massachusetts town of Deerfield.

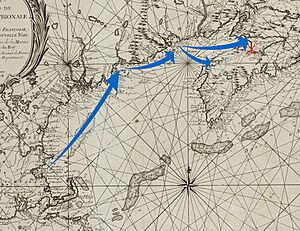

Church's group left Boston on May 25, 1704. They had 500 volunteer soldiers and some Native American allies. They reached the Minas Basin on June 24, after attacking smaller settlements along the way. Even though the famously high tides of the Bay of Fundy made it hard to surprise the town, Church quickly took control of Grand-Pré. For three days, his forces destroyed the town and tried to break the dikes and levees that protected the farmlands.

The farmlands were flooded with saltwater. However, the local Acadians quickly fixed the dikes after the attackers left. This allowed the land to be used for farming again. Church continued his attacks, hitting other communities like Beaubassin before returning to Boston in late July.

Contents

Why the Raid Happened

When the War of the Spanish Succession (also called Queen Anne's War) involved England in 1702, it caused fighting between English and French colonies in North America. Joseph Dudley, the governor of the English Province of Massachusetts Bay, tried to keep the Abenaki people neutral. The Abenaki lived between Massachusetts and New France.

However, the governor of New France, Philippe de Rigaud Vaudreuil, needed Native American support. He encouraged them to join the fight. After a series of attacks on New England in 1703, English colonists tried to get revenge. This led the Abenakis to join a French-led raid on Deerfield, Massachusetts in February 1704.

This raid was very severe. More than 50 villagers were killed, and over 100 were captured. People in Massachusetts wanted revenge. So, Benjamin Church, a skilled fighter, offered to lead an expedition against the French colony of Acadia. Acadia included parts of what are now Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and eastern Maine.

Acadia had many settlements along the Bay of Fundy. Its main town, Port Royal, was the only one with strong defenses. The land around the Minas and Cumberland Basins was important for growing food. Grand Pré was one of the largest and most successful towns in the Minas Basin. In 1701, about 500 people lived there.

French settlers in the area knew how to build dikes and levees. They used these to drain marshlands for farming. These dikes also protected the land from the very high tides of the Bay of Fundy, which can be over 20 feet high. The town of Beaubassin was another large community on the Isthmus of Chignecto.

The Journey Begins

Church had led attacks against Acadia before, during King William's War. Governor Dudley made him a colonel for this new mission. Church's orders were to capture Acadian prisoners. These prisoners could then be traded for English people taken in the Deerfield raid.

The expedition also aimed to punish the Acadians. Church was told to "burn and destroy the enemies houses and break the dams of their corn grounds." However, Governor Dudley specifically told Church not to attack Port Royal. He said he needed permission from London first.

Church gathered about 500 volunteers from Massachusetts coastal areas, including some Native Americans. He left Boston on May 26 with fourteen transport ships and three warships. The warships included the Adventure, Jersey, and Gosport. The Massachusetts Province Galley also joined them. Church brought John Gyles, a former prisoner, as his translator.

The expedition first sailed to Mount Desert Island, near Penobscot Bay. Church sent a group to attack Pentagoet (now Castine, Maine). The French leader, Baron Saint-Castin, was not there. But Church captured his daughter and her children.

Church also learned about a new French settlement at Passamaquoddy Bay. So, the expedition sailed there next. Church sent a small group ashore near what is now St. Stephen, New Brunswick. They destroyed a house and raided a nearby Maliseet camp, killing one Native American.

Church then sent the warships to block the Digby Gut. He hoped they would capture a French supply ship. The main part of the expedition sailed for Grand Pré. On June 24, the three ship captains demanded that Port Royal surrender. They threatened a large attack with 1,700 New Englanders and Native Americans. Governor Jacques-François de Monbeton de Brouillan refused. His defenses were weak, and he only had 150 soldiers. But he saw through the bluff.

Attacking Grand Pré

Colonel Church wrote about these events in his memoirs, published in 1716. French military officers later described the damage caused by the attackers.

Day One: Arrival

On July 3, 1704 (using the New Style calendar), Church arrived at Grand Pré on the ship Adventure. He hoped to surprise the village. Church secretly approached the village from behind Boot Island, which was covered in trees. His men unloaded small boats to go ashore late in the day. They started moving quickly toward the village.

Church sent Lieutenant Giles ahead with a white flag and a written message. It demanded that the village surrender completely.

We do also declare, that we have already made some beginnings of killing and scalping some Canada men, which we have not been wont to do or allow, and are now come with a great number of English and Indians, all volunteers, with resolutions to subdue you, and make you sensible of your cruelties to us, by treating you after the same manner.

– Proclamation of Benjamin Church

Church gave the Acadians and Mi'kmaq people one hour to surrender. He expected to reach the village by then. But Church's group was slowed down by streams that were hard to cross. The tide was going out, making the streams muddy and deep. So, they had to go back to their boats.

Because Church's forces were stuck in the mud, they lost the element of surprise. The Acadians used this chance to leave Grand Pré. They took some of their cattle and their best belongings. Church's forces waited in their boats for the tide to rise. Church thought the high stream banks would offer cover. But when the tide rose that night, it was so high that the boats were exposed. Local soldiers, who had gathered in the woods, fired at them. According to Church, the Acadians and Mi'kmaq "fired smartly at our forces." Church used a small cannon on his boat to fire grape shot at the attackers. They pulled back, with one Mi'kmaq killed and several wounded. Church's forces then waited through the rest of the night.

Day Two: Village Destroyed

The next morning, the Acadian and Mi'kmaq soldiers waited in the woods. Church's men again headed toward the village. Church ordered them to push back any resistance. The largest group of defenders fired from behind trees, but their shots did not hit anyone. They were driven away.

The attackers then entered the village and started taking things. Some men found liquor stores and began drinking. Colonel Church quickly stopped this. They spent the rest of the day destroying much of the village. Church reported that they destroyed 60 houses, 6 mills, and many barns. They also killed about 70 cattle.

At one point, some men saw Acadians driving away cattle. Church sent Lieutenant Barker and some men to chase them. He warned them to be careful. However, Barker was too quick in his chase. He and another man were killed before the attackers went back to the village.

That evening, the attackers built a fort out of logs. They then burned the church and the rest of the village. Church reported that "the whole town seemed to be on fire all at once." All but one home was burned.

Day Three: Crops Ruined

On the morning of the third day, Church ordered his men to destroy the dikes. This would ruin all the crops. Seven dikes were broken. This destroyed most of the harvest and ruined over 200 barrels of stored wheat.

To make the Acadians and Mi'kmaq think his forces were leaving, Church had his soldiers burn the fort they had built. He also had them load themselves and their small boats back onto the transport ships. Some Acadians returned that night and immediately started to fix the broken dikes. However, Church had expected this. He sent men back to the town to drive the Acadians away.

What Happened Next

The next day, Church left Grand Pré. He went on to attack Pisiguit (now Windsor and Falmouth, Nova Scotia), which was near Grand Pré. There, he took 45 prisoners. He then sailed to Port Royal to meet up with the ships blocking the harbor. French reports say that the blocking ships had landed near Port Royal. They burned a few houses and took some prisoners. Governor Brouillan organized defenses that stopped more landings.

After rejoining the warships, Church held a meeting. They discussed whether to launch a large attack against Port Royal. The group decided that their force was "inferiour to the strength of the enemy." They chose to "quit it [Port Royal] wholly and go about [their] other business."

The expedition then sailed back up the Bay of Fundy to Chignecto. There, they raided the village of Beaubassin. Its people had already been warned about the English. Under the leadership of Father Claude Trouve, they had moved their belongings and most of their animals from the village. Church had some small fights with villagers hiding in the woods. He then burned the village's houses and barns and killed 100 cattle. After that, he sailed for Boston. Church reported that six of his men were killed during the entire expedition.

After the Raid

The prisoners Church took were brought to Boston. At first, they were allowed to move freely in the town. But town leaders complained. So, the Acadians were then held at Castle William. They were exchanged in 1705 and 1706 for prisoners taken in the Deerfield raid. The talks were difficult because Governor Dudley at first refused to release a famous French privateer named Pierre Maisonnat dit Baptiste. He was eventually exchanged, along with Noel Doiron and others, for Deerfield's minister, John Williams.

The direct effects of the raid did not last very long. Because the crops and stored grain were destroyed, the colony had a flour shortage that winter. But it was not severe enough to cause major problems. Grand Pré was rebuilt, the dikes were repaired, and there was a good harvest in 1706.

However, the memory of the raid stayed with the people. Even in the 1740s, the people of Grand Pré worried about English attackers returning. They were careful in their dealings with British authorities.

Governor Dudley's choice not to let Church attack Port Royal had political consequences. His opponents in Massachusetts accused him of protecting Port Royal because he was benefiting from illegal trade with Acadia. These accusations continued for several years. Dudley eventually tried to deal with them by launching the failed attacks on Port Royal in 1707.