Battle of Grand Pré facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Grand-Pré |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of King George's War | |||||||

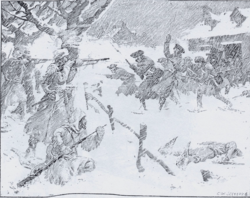

Battle of Grand Pré by Charles William Jefferys |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

Mi'kmaq militia Acadia militia |

|||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Nicolas Antoine II Coulon de Villiers (French commander) Charles Deschamps de Boishébert et de Raffetot Louis de la Corne, Chevalier de la Corne Pierre Maillard |

Arthur Noble † Jedidiah Preble Charles Morris Benjamin Goldthwait Edward How (POW) Erasmus James Philipps |

||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| Acadian militia Wabanaki Confederacy (Mi'kmaq militia and Maliseet militia) Troupes de la marine |

40th Regiment Gorham's Rangers |

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 250-300 | 500 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 53 killed | 67 killed, 40 prisoner, 40 wounded | ||||||

The Battle of Grand Pré, also called the Battle of Minas, was an important fight during King George's War. This war was part of a bigger conflict known as the War of the Austrian Succession. The battle happened in the winter of 1747 in a place called Grand-Pré, which is in modern-day Nova Scotia.

In this battle, forces from New England faced off against a combined group of Canadian, Mi'kmaq, and Acadian fighters. The New England troops were mostly staying in Annapolis Royal. They wanted to take control of the upper part of the Bay of Fundy. The French-led forces, commanded by Nicolas Antoine II Coulon de Villiers and Louis de la Corne, Chevalier de la Corne, launched a surprise attack. They defeated the British soldiers, Massachusetts militia, and rangers who were staying in the village.

Contents

Why the Battle Happened

Grand Pré was a key location. It had been used by French and Mi'kmaq forces to launch attacks on Annapolis Royal in 1744 and 1745. After these attacks, a New England soldier named John Gorham wanted to take control of Grand Pré.

In 1746, the French tried to attack Annapolis Royal again. Their commander, De Ramezay, had to pull back because a large French fleet, the Duc d'Anville expedition, failed.

To stop these attacks from Grand Pré, Governor Shirley sent Colonel Arthur Noble and hundreds of New England soldiers. Their mission was to secure Grand Pré. In December 1746, Captain Charles Morris led one hundred men to Grand Pré. More troops, including those led by Captains Jedidiah Preble and Benjamin Goldthwait, and Colonel Gorham's Rangers, joined them.

Colonel Noble arrived in January 1747 with another hundred men. In total, about five hundred New England soldiers were stationed in Grand Pré. They were spread out in twenty-four houses across the village. Some local people warned the New Englanders that the French might attack. However, the New Englanders didn't believe it. They thought it would be too hard for an army to march through deep snow and frozen rivers.

The Long March to Grand Pré

Many Canadian soldiers were sick after the previous year's fighting. So, De Ramezay gave command of the attack to Captain Coulon de Villiers. On January 21, 1747, the French began a tough 21-day march through winter.

The troops wore snowshoes and used sleds. They traveled across Bay Verte, along the Northumberland shore to Tatamagouche. Then they crossed the Cobequid Mountains to Cobequid Bay near modern-day Truro. By February 2, they reached the Shubenacadie River. The river was frozen and too dangerous to cross with the whole force. De Villiers sent Boishébert with ten men to block roads. This was to prevent anyone from warning the English.

During their journey, Acadian militia and Mi'kmaq warriors joined the Canadian force. Local Acadian families also helped by giving them shelter, food, and information about the English positions. However, some Acadians were not allies. At Cobequid (Truro), de Villiers took steps to block paths. This was to stop any "ill-intentioned inhabitants" from alerting the English.

Since the lower Shubenacadie River was blocked, the main force traveled along the eastern shore. They crossed to the western side where the river was not tidal. They then went overland to the Kennetcook River and on to the Acadian village of Pisiguit. There, villagers gave them more food, as their supplies were low.

By midday on February 10, despite a strong blizzard, the troops were on their final march. They took an old Acadian road over Horton Mountain to Melanson Village. This village was in the Gaspereau Valley, only a few miles from Grand Pré. At Melanson, Acadian guides joined them. These guides led them directly to the houses where the New England soldiers were staying.

The Battle Begins

De Villiers' combined force had about five hundred men. This included Canadians, Mi'kmaq, and Acadians. On the night of February 10, during a blinding snowstorm, the French launched a surprise attack. They targeted ten of the houses where the New Englanders were staying. Most of the New England soldiers were asleep, except for the guards.

The French were very successful at first in the close-up fighting. Colonel Noble, the English commander, was killed. Four other British officers also died. The French took most of the houses, killing over 60 British soldiers. Many attackers also died in the fierce fighting. De Villiers' left arm was badly injured by a musket ball. This wound later led to his death. His second-in-command, La Corne, took over.

The battle continued throughout the village. The British managed to hold onto a few houses. The Canadians also attacked and captured a small fort at Hortonville. They also took two British supply ships docked in the Basin.

Eventually, the British gathered their troops in a strong stone house in the center of the village. About 350 men and some small cannons were inside. In the afternoon, the British tried to leave the stone house to get their supply ships back. But they couldn't get through the deep snow and had to go back to the stone house.

The fighting lasted until the next morning. A cease-fire was arranged because neither side could win. The French couldn't storm the stone house, and the British were running out of ammunition and food. The truce lasted all day. The next morning, the New Englanders agreed to surrender under honorable terms.

Captain Charles Morris reported that 67 New England soldiers were killed, including Colonel Noble. About 40 were taken prisoner, and 40 more were wounded or sick. Morris thought the French lost 30 men. However, Acadians later said that 120 men from both sides were buried. This would mean the French lost about 53 men.

What Happened Next

After the cease-fire, both sides agreed that the British could return to Annapolis Royal. The 350 British soldiers in the stone house were allowed to keep their weapons. They marched back to Annapolis Royal. The French kept the British troops they had captured and the two supply ships. The British marched away with full military honors. This meant they marched through two lines of French soldiers with drums beating and flags flying.

The six-day march back through deep snow was very hard for the New Englanders. They didn't have snowshoes. This caused "extreme fatigues, excessive colds, and difficulties." Many men got sick with fevers when they returned, and about 150 more died.

The French later left Grand-Pré. They went to Noel, Nova Scotia, taking their prisoners and wounded soldiers with them. The most seriously wounded were left with Acadian families in Grand Pré. Some prisoners were released in the spring. Others were sent to Québec and then to Boston.

This battle slowed down the British plans to take control of the upper Bay of Fundy. However, the New Englanders returned to Grand Pré in March 1747. They took over the stone house and made the local people promise to obey the English government again. They also sailed to Pisiguit and burned a ship the Canadian troops had used. The area continued to have conflicts during Father Le Loutre's War. British forces did not move further into the Fundy basin until three years later. After the Battle at Chignecto and the war, the British Army built Fort Lawrence.

Both Nicolas Antoine II Coulon de Villiers and Louis de la Corne, Chevalier de la Corne were given the Order of Saint Louis by the King of France for their bravery in the battle.

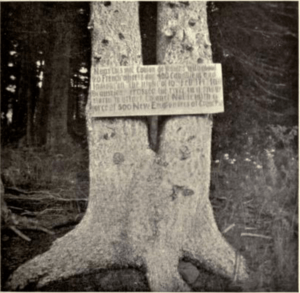

Remembering the Battle

The place where the battle happened was recognized as a special historical site in 1924. The Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada placed a plaque there in 1938.

Many writers have explored this battle in their works. The historian and poet Mary Jane Katzmann Lawson wrote a poem called "The Battle of Grand Pre" around 1820. Merrill Denison wrote a radio play, "The Raid on Grand Pre," in 1931. Archibald MacMechan wrote a book called "Red Snow on Grand Pré" in the same year.

One Acadian who was with the French during this battle was Zedore Gould. He was 20 years old at the time. He later escaped the Expulsion of the Acadians and lived to be very old. He loved to tell stories about his experiences in this famous event in Nova Scotian history.

Images for kids

-

Erasmus James Philipps, Old Burying Ground (Halifax, Nova Scotia)

| Madam C. J. Walker |

| Janet Emerson Bashen |

| Annie Turnbo Malone |

| Maggie L. Walker |