Pierre Maillard facts for kids

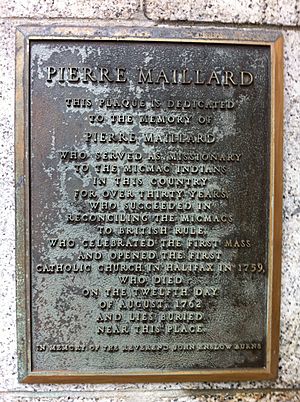

Abbé Pierre Antoine Simon Maillard (born around 1710 – died August 12, 1762) was a Catholic priest from France. He is famous for helping to create a writing system for the Mi'kmaq Indigenous people of Cape Breton Island, Canada. He also helped make a peace treaty between the British and the Mi'kmaq. This led to a special event called the Burying the Hatchet Ceremony. Maillard was the first Catholic priest in Halifax. He is buried in St. Peter's Cemetery in downtown Halifax.

Contents

Early Life and Work

Maillard was born in France around 1710. He studied to become a priest in Paris. In 1735, he was chosen to work as a missionary with the Mi'kmaq people on Cape Breton Island. At that time, this island was called Île Royale. His recommendation letter said he was a "young priest who has greatly edified us . . full of zeal and piety."

Maillard arrived at Fortress Louisbourg on August 13, 1735. He spent a lot of time with the Mi'kmaq people. He saw firsthand the fights between French and British forces for control of the area. He even became involved in these struggles.

Maillard quickly learned the Mi'kmaq language very well. He also traveled to many settlements on Île Royale, Prince Edward Island (then called Île Saint-Jean), and Nova Scotia (then called English Acadia). He asked his French leaders for more help. They sent another priest named Jean-Louis Le Loutre. The two priests worked together to develop the Mi'kmaq written language.

In 1740, Maillard was given an important role as the Bishop of Quebec's representative for Île Royale. He continued his work, focusing on helping the Mi'kmaq people.

King George's War

During a conflict known as King George's War, Maillard supported the Mi'kmaq, French, and Acadians. He was present when Annapolis Royal was under attack in 1745. After the British took Louisbourg in June 1745, Maillard encouraged Mi'kmaq warriors to attack British forces.

In late 1745, the British captured Maillard and sent him to Boston. From there, he was sent back to France. However, he quickly returned to Acadia in 1746 with the Duc d'Anville expedition. This expedition was planned with Father Le Loutre. Maillard actively took part in military actions during the winter of 1746-47, such as the Battle of Grand Pré.

Father Le Loutre's War

During Father Le Loutre's War, Maillard encouraged the Mi'kmaq to declare war against the British. He was involved in resisting the founding of Halifax, Nova Scotia in the summer of 1749. The Governor of Halifax, Edward Cornwallis, tried to get Maillard to leave the area.

In response, King Louis XV of France gave Maillard a yearly payment in 1750. Another assistant, Abbé Jean Manach, was sent to help Maillard. From his mission on Île de la Sainte-Famille, Maillard continued to encourage his Mi'kmaq contacts to resist until 1758.

Maillard used his own money to build structures for religious efforts starting in 1754. These were on Île de la Sainte-Famille, now called Chapel Island. This was in the south of Bras d'Or Lake, where his main mission was located.

French and Indian War

During the French and Indian War, Maillard moved to Malagomich (now Merigomish, Nova Scotia) in 1758. He did this to get away from the growing British presence. On November 26, 1759, he and other French missionaries accepted a peace offer from British Major Schomberg.

Because of this, a French military officer accused the missionaries of treason. He sent an officer to investigate in 1760. Maillard sent a letter to this officer. In it, he explained the very difficult situation of the Mi'kmaq. He said he had worked for 23 years "in this country in the service of our Religion and our Prince." He explained that he had sought peace with the British because the situation was hopeless.

Soon after, Maillard accepted an invitation from Nova Scotia Governor Charles Lawrence. He traveled to Halifax to help make peace with the Mi'kmaq people. He became a British official, known as the "Government Agent to the Indians." He received a yearly salary. He was allowed to hold Catholic services for Acadians and Mi'kmaqs in Halifax. In his role, Maillard helped most tribal chiefs sign peace treaties with the British in Halifax.

Death

In July 1762, Maillard became very sick. He died on August 12, 1762. At his request, an Anglican clergyman named Thomas Wood was with him. The Nova Scotia Governor gave Maillard a State Funeral. Important people, like the Council President, were his pallbearers. The government recognized his important role in making peace treaties between the Mi'kmaq and the British. He was first buried in an unmarked grave in the Old Burying Ground in downtown Halifax.

After St. Peter's Cemetery opened in 1784, Maillard's grave was moved there. It remains unmarked today under a parking lot built on top of the cemetery.

Reverend Wood wrote about Maillard:

"He was a very sensible, polite, well bred man, an excellent scholar and a good sociable companion, and was much respected by the better sort of people here as it appeared."

Before he died, Maillard gave away all his belongings. Most of his books went to important collections of the time. His other items were given to Louis Petitpas, who was his only companion and trusted helper since 1749. Maillard had lived in Petitpas's home while in Halifax.

Legacy

When Maillard arrived in Louisbourg, he immediately started learning the Mi'kmaq language. His teacher was the Abbé de Saint-Vincent. Maillard was very good at languages. Within a few months, he mastered the spoken language. During the winter of 1737-38, he created a system of hieroglyphics to write down Mi'kmaq words.

He used these symbols to write down important prayers and responses for the catechism. This helped his followers learn them more easily. Jean-Louis Le Loutre, another French missionary, greatly helped him with this. Le Loutre was amazed by Maillard's achievements. He later wrote:

" . . a naturalized Indian as regards language . . [he succeeded in acquiring the gift of rhyming at each member of a sentence, being able to] . . speak Micmac with as much ease and purity as do their women who are the most skilled in this style."

Experts generally agree that Maillard did not invent the Mi'kmaq hieroglyphics. In 1691, Father Chrestien Le Clercq reported that he had created a similar method. He used it to teach the Mi'kmaq people of the Gaspé Peninsula. It seems he had organized and expanded the Mi'kmaq custom of using pictures to write short messages. There is no direct proof that Maillard knew about Le Clercq's work. However, Maillard's work is special because he left many writings in the language. These writings continued to be used by the Mi'kmaq people into the 20th century.

See also

| Calvin Brent |

| Walter T. Bailey |

| Martha Cassell Thompson |

| Alberta Jeannette Cassell |