Military history of the Mi'kmaq facts for kids

The military history of the Mi'kmaq is about Mi'kmaq warriors, called smáknisk. They fought in wars against the English (who became the British after 1707). They fought on their own and also with Acadian militias and French royal forces.

Mi'kmaq fighters were strong for over 75 years. This was before the Halifax Treaties were signed in 1760–1761. In the 1800s, the Mi'kmaq proudly said they "killed more men than they lost" against the British.

In 1753, Charles Morris noted that the Mi'kmaq were hard to find. They had "no settlement or place of abode." They moved "from place to place in unknown... inaccessible woods." This made it very hard to surprise them.

Leaders on both sides used common colonial warfare tactics. After some fights with the British during the American Revolutionary War, the militias were quiet. The Mi'kmaq people then used diplomacy to make sure their treaties were honored. Later, Mi'kmaq warriors joined Canada's efforts in World War I and World War II.

Famous Mi'kmaq leaders during colonial times were Chief (Sakamaw) Jean-Baptiste Cope and Chief Étienne Bâtard.

Contents

- Early Conflicts: 1500s

- Conflicts in the 1600s

- Conflicts in the 1700s

- 1800s: A Time of Change

- 1900s: Joining Canada's Wars

- Notable Mi'kmaq Veterans

- See also

Early Conflicts: 1500s

Battle at Bae de Bic (1534)

In the spring of 1534, a big battle happened at Bae de Bic. This area was a yearly meeting place for the Mi'kmaq along the St. Lawrence River. According to Jacques Cartier, 100 Iroquois warriors attacked 200 Mi'kmaq. The Mi'kmaq were camped on Massacre Island.

Mi'kmaq scouts warned their village the night before the attack. They moved 30 sick and elderly people to safety. About 200 Mi'kmaq left their camp on the shore. They went to an island in the bay. They hid in a cave and covered the entrance with branches.

The Iroquois arrived at the empty village the next morning. They searched but did not find the Mi'kmaq until the following day. Mi'kmaq warriors defended their people against the first Iroquois attack. Many were wounded on both sides. As the tide rose, the Mi'kmaq pushed back the Iroquois. The Iroquois went back to the mainland.

The Mi'kmaq built defenses on the island. They got ready for the next attack at low tide. The Iroquois attacked again but were pushed back. They retreated to the mainland as the tide rose. The next morning, the tide was low again. The Iroquois made their final attack. They used arrows with fire. These arrows burned down the Mi'kmaq defenses. The fire wiped out the Mi'kmaq. Twenty Iroquois were killed and thirty were wounded. The Iroquois then split into two groups to go back to their canoes.

Battle at Bouabouscache River

Before the Battle at Bae de Bic, Iroquois warriors had hidden their canoes and supplies. Mi'kmaq scouts found these hidden items. They got help from 25 Maliseet warriors. The Mi'kmaq and Maliseet fighters ambushed the first group of Iroquois. They killed ten and wounded five Iroquois warriors. The second Iroquois group arrived, and the Mi'kmaq/Maliseet fighters retreated unharmed into the woods.

The Mi'kmaq/Maliseet group had stolen most of the Iroquois canoes. Fifty Iroquois went to find their hidden supplies. They left twenty wounded behind. They could not find their supplies. When they returned to camp, they found the 20 wounded soldiers had been killed.

The next morning, 38 Iroquois warriors left their camp. They killed twelve of their own wounded who could not travel. Ten Mi'kmaq/Maliseet stayed with the stolen canoes and supplies. The other 15 chased the Iroquois. They chased the Iroquois for three days. They killed eleven more wounded Iroquois who fell behind.

Battle at Riviere Trois Pistoles

Soon after the Bouabouscache River battle, the Iroquois set up camp. They were on the Riviere Trois Pistoles. They wanted to build canoes to go home. An Iroquois hunting party went to find food. The Mi'kmaq/Maliseet fighters killed the hunting party.

The Iroquois went to find their missing hunters. They were ambushed by the Mi'kmaq/Maliseet. Nine Iroquois were killed. Twenty-nine warriors retreated to their camp. The Mi'kmaq/Maliseet split into two groups. They attacked the remaining Iroquois. Three Maliseet warriors died, and many others were wounded. The Mi'kmaq/Maliseet won the battle. They killed all but six Iroquois. These six were taken prisoner and later killed.

Kwedech–Mi'kmaq War

Stories say there was a war in the 1500s. It was between the Kwedech (St. Lawrence Iroquois) and the Mi'kmaq. A great Mi'kmaq chief named Ulgimoo led his people. The Mi'kmaq pushed the Kwedech out of the Maritimes. The conflict ended with a peace treaty.

Conflicts in the 1600s

Some Mi'kmaq lived in New England. They were known as Tarrantines. In 1619, 300 Tarrantine warriors killed Nanepashemet and his wife at Mystic Fort. This death ended the Massachusetts Federation.

Penobscot–Tarrantine War

Before 1620, the Penobscot-Tarrantine War happened in Maine. The Pawtucket Tribe supported the Penobscot. This led to later attacks by the Tarrantines on the Pawtucket and Agawam Tribes. In 1633, Tarrantines attacked Chief Masconomet's camp at Agawam.

King Philip's War

The first recorded fight between the Mi'kmaq and the British was during the First Abenaki War. This was part of King Philip's War. It included the Battle of Port La Tour (1677). After King Philip's War, the Mi'kmaq joined the Wapnáki. This was an alliance with four other Algonquian-speaking nations. These were the Abenaki, Penobscot, Passamaquoddy, and Maliseet. This group was called the Wabanaki Confederacy.

The Wabanaki Confederacy teamed up with French colonists in Acadia. For 75 years, during six wars, the Mi'kmaq fought. They wanted to stop the British from taking over their land. The first war with many Mi'kmaq fighters was King William's War.

King William's War

During King William's War, Mi'kmaq fighters helped defend against British movement into their lands. They fought the British along the Kennebec River in southern Maine. This river was the natural border between Acadia and New England.

The Mi'kmaq and Maliseet fighters worked from their base at Meductic. They joined French attacks on Bristol, Maine (the Siege of Pemaquid (1689)), Salmon Falls, and Portland, Maine. Mi'kmaq tortured British prisoners from these fights. In return, New Englanders attacked Port Royal and Guysborough.

In 1692, Mi'kmaq from all over the region joined the Raid on Wells. In 1694, the Maliseet took part in the Raid on Oyster River in Durham, New Hampshire.

Two years later, New France, led by Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville, returned. They fought a naval battle in the Bay of Fundy. Then they raided Bristol, Maine again. Before this battle, on July 5, 140 Native people (Mi'kmaq and Maliseet) ambushed four English ships' crews. Some English were getting firewood. A Native killed five of nine men in a boat. The Mi'kmaq burned the ship.

To get back at them for the siege of Pemaquid, New Englanders attacked Chignecto. They also attacked the capital of Acadia at Fort Nashwaak. After the Pemaquid siege, d'Iberville led 124 Canadians, Acadians, Mi'kmaq, and Abenaki. They destroyed almost every English settlement in Newfoundland. Over 100 English were killed. Many more were captured. Almost 500 were sent to England or France.

Conflicts in the 1700s

Queen Anne's War

During Queen Anne's War, Mi'kmaq fighters again defended their lands. They made many attacks along the Acadia/New England border. They raided New England settlements in the Northeast Coast Campaign.

To get back at them for the Mi'kmaq raids, Major Benjamin Church went on his last trip to Acadia. He raided Castine, Maine. Then he raided Grand Pre, Pisiquid, and Chignecto. In 1705, Mi'kmaq killed a fisherman near Cape Sables. A few years later, Captain March failed to capture Port Royal, the capital of Acadia. The New Englanders did capture Port Royal in 1710. The Wabanaki Confederacy won the nearby Battle of Bloody Creek (1711) in 1711.

The Treaty of Utrecht in 1713 ended Queen Anne's War. It confirmed that Acadia (mainland Nova Scotia) was now British. New Brunswick and most of Maine were still disputed. New England gave up Île St Jean (Prince Edward Island) and Île Royale (Cape Breton) to the French. The French built a strong fort at Louisbourg on Cape Breton. In 1712, the Mi'kmaq captured over twenty New England fishing boats off Nova Scotia.

In 1715, the Mi'kmaq learned that the British claimed their land. This was due to the Treaty of Utrecht, which the Mi'kmaq were not part of. They complained to the French commander at Louisbourg. They said the French king could not give away their land. They were then told that the French had claimed their country for a century. This was based on laws made by kings in Europe.

Native people did not accept British rule in Nova Scotia. The British tried to settle near Mi'kmaq trading posts at Canso and Annapolis. On May 14, 1715, Cyprian Southack tried to set up a fishing station at "Cape Roseway" (now Shelburne, Nova Scotia). In July 1715, the Mi'kmaq raided and burned it down. Two Boston merchants said the Mi'kmaq claimed the land was theirs. They said the Mi'kmaq could "make Warr and peace when they please." Southack then raided Canso, Nova Scotia in 1718. He told Governor Phillips to fortify Canso.

Father Rale's War (1722–1725)

Before Father Rale's War, some Mi'kmaq raided Fort William Augustus at Canso, Nova Scotia in 1720. In May 1722, Lieutenant Governor John Doucett took 22 Miꞌkmaq hostage at Annapolis Royal. He wanted to stop attacks on the capital. In July 1722, the Abenaki and Mi'kmaq blocked Annapolis Royal. They wanted to starve the capital. They captured 18 fishing boats and prisoners from Yarmouth, Nova Scotia to Canso, Nova Scotia. They also took prisoners and boats from the Bay of Fundy.

Because of the growing conflict, Massachusetts Governor Samuel Shute declared war on July 22, 1722. The first battle of Father Rale's War happened in Nova Scotia. To end the blockade of Annapolis Royal, New England launched a campaign. They wanted to get back over 86 New England prisoners. One of these actions led to the Battle at Jeddore.

Raid on Georgetown (1722)

On September 10, 1722, 400 or 500 St. Francis and Miꞌkmaq warriors attacked Georgetown (Arrowsic, Maine). Captain Penhallow fired from a small guard. Three Indians were wounded and one was killed. This defense gave villagers time to hide in the fort. The Indians took over the undefended village. They killed fifty cattle and burned twenty-six houses outside the fort. Then they attacked the fort, killing one New Englander. Georgetown was burned.

That night, Colonel Walton and Captain Harman arrived with thirty men. About forty men from the fort joined them. The combined force of seventy men attacked the Native people. But they were outnumbered. The New Englanders went back into the fort. The Indians saw that attacking the fort was useless. They eventually left and went up the river.

On their way back, the Native people attacked Fort Richmond. It was a three-hour siege. Houses were burned and cattle killed, but the fort held. Brunswick and other settlements near the Kennebec River were burned. The next attack was on Canso, Nova Scotia in 1723.

During the 1724 Northeast Coast campaign, Mi'kmaq from Cape Sable Island helped. The Native people also fought at sea. In just a few weeks, they captured 22 ships. They killed 22 New Englanders and took more prisoners. They also failed to capture St. George's Fort in Thomaston, Maine.

In early July 1724, sixty Mi'kmaq and Maliseet attacked Annapolis Royal. They killed a sergeant and a private. Four more soldiers were wounded. They scared the village. They also burned houses and took prisoners. The British killed one Mi'kmaq hostage where the sergeant was killed. They also burned three Acadian houses in return.

Because of the raid, three blockhouses were built to protect the town. The Acadian church was moved closer to the fort for better monitoring. In 1725, sixty Abenaki and Mi'kmaq attacked Canso again. They destroyed two houses and killed six people.

The treaty that ended the war was important. It was the first time a European empire said it needed to talk with Native people about ruling Nova Scotia. This treaty was used in the Donald Marshall case as recently as 1999.

King George's War (1744–1748)

News of war reached the French fortress at Louisbourg first, on May 3, 1744. They quickly started fighting, which became King George's War. Within a week, a military trip to Canso was planned. On May 23, a group of ships left Louisbourg harbor. That same month, British Captain David Donahue captured Mi'kmaq chief Jacques Pandanuques and his family near Île-Royale. Donahue killed the chief. Donahue used a trick, pretending to be a French ship. He used this same trick in the Naval battle off Tatamagouche, where he was later killed by the Mi'kmaq.

The Mi'kmaq and French were worried about their supply lines to Quebec. They also wanted revenge for their chief's death. They first raided the British fishing port of Canso on May 23. In response, Governor Shirley of Massachusetts declared war on the Mi'kmaq.

The Mi'kmaq and French then planned an attack on Annapolis Royal, the capital of Nova Scotia. But French forces were slow to leave Louisbourg. Their Mi'kmaq and Maliseet allies decided to attack on their own in early July. Annapolis knew about the war. They were somewhat ready when the Native people started attacking Fort Anne. The Native people did not have heavy weapons. They left after a few days.

In mid-August, a larger French force arrived at Fort Anne. But they also could not attack effectively. The fort was helped by Gorham's Rangers. Gorham led his Native rangers in a surprise raid on a Mi'kmaq camp nearby. They killed women and children. The Mi'kmaq left, and Duvivier had to retreat to Grand Pre on October 5.

During the siege of Annapolis Royal, the Mi'kmaq and Maliseet captured William Pote and some of Gorham's Rangers. Pote was taken to the Maliseet village of Aukpaque. While there, Mi'kmaq from Nova Scotia arrived. On July 6, 1745, they tortured Pote and a Mohawk ranger named Jacob. This was revenge for Ranger John Gorham killing their family members. On July 10, Pote saw another act of revenge. The Mi'kmaq tortured another Mohawk ranger at Meductic.

Many Mi'kmaq warriors and French Officer Paul Marin de la Malgue were stopped from helping Louisbourg. Captain Donahew defeated them in the naval battle off Tatamagouche. He had also killed the Mi'kmaq chief of Cape Breton earlier. In 1745, British forces captured Port Toulouse (St. Peter's). Then they captured Fortress Louisbourg after a six-week siege.

Weeks after Louisbourg fell, Donahew and Fones fought Marin again. Marin was near the Strait of Canso. Donahew and 11 of his men landed. They were immediately surrounded by 300 Native people. The captain and five of his men were killed. The other six were taken prisoner. On July 19, Donahew's ship sailed into the harbor with its flags at half-mast. The terrible story of what happened to Captain David Donahew and his crew spread quickly. Miꞌkmaw fighters stayed outside Louisbourg. They attacked anyone who went for firewood or food.

In response to the siege of Louisbourg, Mi'kmaq warriors joined the Northeast Coast campaign. It started on July 19. Mi'kmaq from Nova Scotia, Maliseet, and some from St. Francois attacked Fort St. George (Thomaston) and New Castle. They burned many buildings. They killed cattle and took one villager captive. They also killed a person at Saco.

In 1745, Mi'kmaq killed seven English crew members at LaHave, Nova Scotia. The English did not dry fish on the east coast of Acadia. They were afraid of being killed by the Mi'kmaq. By the end of 1745, French reports said the English were afraid of the Native people. They said the French were under Native "protection."

France launched a large expedition to get Acadia back in 1746. But storms, disease, and the death of its commander, the Duc d'Anville, stopped it. It returned to France in bad shape. The disease then spread to the Mi'kmaq tribes, killing hundreds.

Newfoundland Attacks

In response to the Newfoundland campaign, Mi'kmaq fighters from Île-Royale raided British outposts in Newfoundland in August 1745. They attacked several British houses and took 23 prisoners. The next spring, the Mi'kmaq started taking 12 prisoners to a meeting point near St. John's. They were on their way to Quebec. The British prisoners managed to kill their Mi'kmaq captors at the meeting site. Two days later, another Mi'kmaq group took the remaining 11 British prisoners to the same spot. When they found out what happened to the other Mi'kmaq, they killed the remaining 11 British prisoners.

Father Le Loutre's War (1749–1755)

Even after the British captured Acadia in 1710, Nova Scotia was mostly home to Catholic Acadians and Mi'kmaq. To stop Protestant settlements, Mi'kmaq raided early British settlements. These included Shelburne (1715) and Canso (1720).

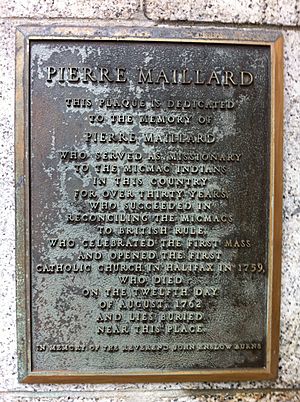

A generation later, Father Le Loutre's War began. Edward Cornwallis arrived to start Halifax on June 21, 1749. Historian William Wicken says that by starting Halifax without talking to them, the British broke earlier treaties with the Mi'kmaq (1726). These treaties were signed after Father Rale's War.

The British quickly built other settlements. To protect against Mi'kmaq, Acadian, and French attacks, the British built forts. These were in Halifax (Citadel Hill) (1749), Bedford (Fort Sackville) (1749), Dartmouth (1750), Lunenburg (1753), and Lawrencetown (1754). There were many Miꞌkmaw and Acadian raids on these villages, like the Raid on Dartmouth (1751).

Within 18 months of starting Halifax, the British also took strong control of peninsula Nova Scotia. They built forts in all major Acadian communities. These included Windsor (Fort Edward), Grand Pre (Fort Vieux Logis), and Chignecto (Fort Lawrence). A British fort was already at Annapolis Royal. Cobequid did not have a fort. There were many Mi'kmaq and Acadian raids on these forts.

Raid on Dartmouth (1749)

The Mi'kmaq saw the founding of Halifax without talking to them as breaking earlier agreements. On September 24, 1749, the Mi'kmaq formally said they were against British settlement plans. On September 30, 1749, about forty Mi'kmaq attacked six men. These men were cutting trees near a sawmill in Dartmouth, Nova Scotia. Four men were killed, one was captured, and one escaped. Major Gilman and others escaped and raised the alarm. Rangers were sent after the attackers. This was the first of eight raids on Dartmouth during the war.

Siege of Grand Pre (1749)

Two months later, on November 27, 1749, 300 Mi'kmaq, Maliseet, and Acadians attacked Fort Vieux Logis. This fort was new and built by the British in Grand Pre. Captain Handfield commanded the fort. The Native and Acadian fighters killed the guards who were shooting at them. Then they captured Lieutenant John Hamilton and eighteen soldiers. These soldiers were checking the area around the fort.

After the soldiers were captured, the Native and Acadian groups tried several times to attack the fort. They stopped fighting after about a week. Gorham's Rangers were sent to help the fort. When they arrived, the attackers had already left with the prisoners. The prisoners were held for several years before being set free for money. There was no fighting during the winter, which was common in frontier wars.

Battle at St. Croix (1750)

The next spring, on March 18, 1750, John Gorham and his Rangers left Fort Sackville. They were ordered by Governor Cornwallis to go to Piziquid (now Windsor, Nova Scotia). Gorham's job was to build a blockhouse at Piziquid, which became Fort Edward. He also had to take property from Acadians who had fought in the Siege of Grand Pre.

Around noon on March 20, Gorham and his men arrived at the Acadian village of Five Houses. It was next to the St. Croix River. All the houses were empty. Gorham saw Mi'kmaq hiding in bushes on the other side of the river. The Rangers opened fire. The fight turned into a siege. Gorham's men took cover in a sawmill and two houses. During the fight, three Rangers were wounded, including Gorham. He was shot in the thigh. As the fighting got worse, they sent for help from Fort Sackville.

On March 22, Governor Cornwallis sent Captain William Clapham's and Captain St. Loe's Regiments. They had two field guns. These extra troops and artillery helped Gorham. They forced the Mi'kmaq to leave. Gorham then went to Windsor. He made Acadians take down their church, Notre Dame de l'Assomption. Fort Edward was built in its place.

Raids on Halifax (1750-1753)

There were four raids on Halifax during the war. The first raid was in October 1750. Mi'kmaq captured six men in the woods on the Halifax peninsula. Another writer, Thomas Akins, says this raid was in July. He says four of the six British attacked were captured and never seen again. Soon after, Cornwallis learned that the Mi'kmaq had been paid by the French for five prisoners from Halifax. They also got paid for prisoners taken earlier at Dartmouth and Grand Pre.

In 1751, there were two attacks on blockhouses around Halifax. Mi'kmaq attacked the North Blockhouse and killed the guards. Mi'kmaq also attacked near the South Blockhouse. This was at a sawmill on a stream from Chocolate Lake into the Northwest Arm. They killed two men.

Raids on Dartmouth (1750-1751)

There were six raids on Dartmouth during this time. In July 1750, the Mi'kmaq killed 7 men working in Dartmouth. In August 1750, 353 people arrived on the Alderney. They started the town of Dartmouth. The town was planned that autumn. The next month, on September 30, 1750, Dartmouth was attacked again. Five more residents were killed. In October 1750, about eight men went out for fun. They were hunting birds. The Native people attacked them and took them all prisoner.

The next spring, on March 26, 1751, the Mi'kmaq attacked again. They killed fifteen settlers and wounded seven. Three of the wounded later died. They took six captives. The soldiers who chased the Mi'kmaq fell into a trap. They lost a sergeant. Two days later, on March 28, 1751, Mi'kmaq took three more settlers.

Two months later, on May 13, 1751, Broussard led sixty Mi'kmaq and Acadians. They attacked Dartmouth again in what was called the "Dartmouth Massacre." Broussard and his group killed twenty settlers and took more prisoners. A sergeant was also killed. They destroyed buildings. Captain William Clapham and sixty soldiers fired from the blockhouse. The British killed six Mi'kmaq warriors. Those at a camp at Dartmouth Cove, led by John Wisdom, helped the settlers. The next day, they found the Mi'kmaq had also raided their camp and taken a prisoner.

In 1752, Mi'kmaq attacks on the British along the coast were frequent. Fishermen had to stay on land because they were main targets. In early July, New Englanders killed two Mi'kmaq girls and one boy off Cape Sable. In August, at St. Peter's, Nova Scotia, Mi'kmaq seized two schooners. These were the Friendship from Halifax and the Dolphin from New England. They took 21 prisoners who were later set free for money.

On September 14, 1752, Governor Peregrine Hopson and the Nova Scotia Council made the 1752 Peace Treaty with Jean-Baptiste Cope. The treaty was officially signed on November 22, 1752. Cope could not get other Mi'kmaq leaders to support the treaty. Cope burned the treaty six months after he signed it. Even though peace failed on the eastern shore, the British did not officially reject the 1752 Treaty until 1756.

Attack at Mocodome (1753)

On February 21, 1753, nine Mi'kmaq from Nartigouneche (now Antigonish, Nova Scotia) attacked a British ship. It was at Country Harbour, Nova Scotia. The ship was from Canso, Nova Scotia and had four crew members. The Mi'kmaq fired on them and pushed them toward the shore. Other Native people joined and boarded the ship. They forced it into an inlet. The Mi'kmaq killed two British and captured two others. After seven weeks, on April 8, the two British prisoners killed six Mi'kmaq and escaped.

Attack at Jeddore (1753)

In response, on the night of April 21, Chief Jean-Baptiste Cope and the Mi'kmaq attacked another British schooner. This was a battle at sea off Jeddore, Nova Scotia. There were nine British men and one Acadian (Casteel), who was the pilot. The Mi'kmaq killed the British. They let the Acadian off at Port Toulouse. The Mi'kmaq sank the schooner after taking its goods. In August 1752, the Mi'kmaq at Saint Peter's seized the schooners Friendship and Dolphin. They took 21 prisoners for ransom.

Raid on Halifax (1753)

In late September 1752, Mi'kmaq caught a man outside the Palisade of Fort Sackville. In 1753, when Lawrence became governor, the Mi'kmaq attacked again. They attacked the sawmills near the South Blockhouse on the Northwest Arm. They killed three British. On the other side of the harbor in Dartmouth, in 1753, there were only five families. All refused to farm. They were afraid of being attacked if they left the village's fenced area. In May 1753, Native people attacked two British soldiers at Fort Lawrence.

Raid on Lawrencetown (1754)

In 1754, the British started Lawrencetown on their own. In late April 1754, Beausoleil and a large group of Mi'kmaq and Acadians left Chignecto for Lawrencetown. They arrived in mid-May. At night, they opened fire on the village. Beausoleil killed four British settlers and two soldiers. By August, as raids continued, residents and soldiers were moved to Halifax. By June 1757, settlers had to be completely removed from Lawrencetown. This was because Native raids stopped settlers from leaving their homes.

A well-known Halifax businessman, Michael Francklin, was captured by a Mi'kmaq raiding party in 1754. He was held captive for three months.

French and Indian War (1754–1763)

The last colonial war was the French and Indian War. The British captured Acadia in 1710. For the next 45 years, Acadians refused to fully promise loyalty to Britain. During this time, Acadians fought against the British. They also kept important supply lines open to the French forts of Louisbourg and Fort Beausejour.

During the French and Indian War, the British wanted to stop any military threat from Acadians and Mi'kmaq. This was especially true near the New England border in Maine. The British wanted to prevent future attacks from the Wabanaki Confederacy, French, and Acadians. The British saw the Acadians' loyalty to the French and Wabanaki as a military danger. Father Le Loutre's War had led to total war. British civilians were not spared. Governor Charles Lawrence and the Nova Scotia Council believed Acadian civilians helped the enemy. They gave information, shelter, and supplies. Others fought against the British.

In Acadia, the British also wanted to stop Acadians from supplying Louisbourg. They did this by deporting Acadians from Acadia. Defeating Louisbourg would also mean defeating the ally who gave the Mi'kmaq ammunition.

The British started the Expulsion of the Acadians with the Bay of Fundy Campaign (1755). Over the next nine years, more than 12,000 Acadians were removed from Nova Scotia. Acadians were sent across the Atlantic. They went to the Thirteen Colonies, Louisiana, Quebec, Britain, and France. Very few ever returned to Nova Scotia. During the expulsion, Acadian and Native resistance to the British grew stronger.

During the expulsion, French Officer Charles Deschamps de Boishébert led the Mi'kmaq and Acadians in a guerrilla war against the British. Louisbourg records show that by late 1756, the French regularly gave supplies to 700 Native people.

Raids on Annapolis (Fort Anne)

Acadians and Mi'kmaq fought in the Annapolis area. They won the Battle of Bloody Creek (1757). Acadians being deported from Annapolis Royal on the ship Pembroke fought against the British crew. After fighting off another British ship on February 9, 1756, the Acadians took 8 British prisoners to Quebec.

In December 1757, Mi'kmaq warriors captured John Weatherspoon. He was cutting firewood near Fort Anne. They took him to the Miramichi River. From there, he was sold or traded to the French. He was taken to Quebec and held until late 1759. This was when General Wolfe's forces won the Battle of the Plains of Abraham.

About 50 or 60 Acadians escaped the first deportation. They went to the Cape Sable region (southwestern Nova Scotia). From there, they made many raids on Lunenburg, Nova Scotia.

Raids on Piziquid (Fort Edward)

In April 1757, Acadians and Mi'kmaq raided a warehouse near Fort Edward. They killed thirteen British soldiers. After taking what supplies they could, they burned the building. A few days later, the same group raided Fort Cumberland. British officer John Knox wrote that in 1757, the British were supposedly "Masters of the province of Nova Scotia." But he said this was "only an imaginary possession." He added that the situation was so dangerous for the British. The "troops and inhabitants" at Fort Edward, Fort Sackville, and Lunenburg "could not be reputed in any other light than as prisoners."

Raids on Chignecto (Fort Cumberland)

Acadians and Mi'kmaq also fought in the Chignecto area. They won the Battle of Petitcodiac (1755). In spring 1756, a wood-gathering party from Fort Monckton was ambushed. In April 1757, after raiding Fort Edward, the same Acadian and Mi'kmaq group raided Fort Cumberland. They killed two men and took two prisoners. On July 20, 1757, Mi'kmaq killed 23 and captured two of Gorham's rangers. This was outside Fort Cumberland near Jolicure, New Brunswick.

In March 1758, forty Acadians and Mi'kmaq attacked a schooner at Fort Cumberland. They killed its master and two sailors. In winter 1759, the Mi'kmaq ambushed five British soldiers. They were on patrol crossing a bridge near Fort Cumberland. On the night of April 4, 1759, Acadians and French captured a transport ship using canoes. At dawn, they attacked the ship Moncton. They chased it for five hours down the Bay of Fundy. The Moncton escaped, but its crew had one killed and two wounded.

Others resisted during the St. John River Campaign and the Petitcodiac River Campaign.

Raids on Lawrencetown (1757)

By June 1757, settlers had to be completely removed from Lawrencetown. This was because Native raids stopped settlers from leaving their homes. On July 30, 1757, Mi'kmaq fighters killed three Roger's Rangers at Lawrencetown. In nearby Dartmouth, Nova Scotia, in spring 1759, there was another Mi'kmaq attack on Eastern Battery. Five soldiers were killed.

Raids on Maine (1755-1758)

In present-day Maine, the Mi'kmaq and Maliseet raided many New England villages. In late April 1755, they raided Gorham, Maine. They killed two men and a family. Next, they appeared in New Boston (Gray) and nearby towns. They destroyed farms. On May 13, they raided Frankfort (Dresden). Two men were killed and a house burned. The same day, they raided Sheepscot (Newcastle) and took five prisoners. Two were killed in North Yarmouth on May 29, and one was captured. They shot one person at Teconnet. They took prisoners at Fort Halifax. Two prisoners were taken at Fort Shirley (Dresden). They took two captives at New Gloucester while they worked on the local fort.

On August 13, 1758, Boishebert left Miramichi, New Brunswick with 400 soldiers. This included Acadians he led from Port Toulouse. They marched to Fort St George (Thomaston, Maine) and Munduncook (Friendship, Maine). The siege of Fort St George failed. But in the raid on Munduncook, they wounded eight British settlers and killed others. This was Boishébert's last Acadian trip. From there, Boishebert and the Acadians went to Quebec. They fought in the Battle of Quebec (1759).

Raids on Lunenburg (1756-1759)

Acadians and Mi'kmaq raided the Lunenburg settlement nine times in three years. Boishebert ordered the first Raid on Lunenburg. After the 1756 raid, in 1757, there was a raid on Lunenburg. Six people from the Brissang family were killed. The next year, the Lunenburg Campaign (1758) began. There was a raid on the Lunenburg Peninsula at the Northwest Range (now Blockhouse, Nova Scotia). Five people from the Ochs and Roder families were killed. By the end of May 1758, most people on the Lunenburg Peninsula left their farms. They went to the safety of the forts around Lunenburg town. They lost the planting season. For those who stayed on their farms, the number of raids increased.

In summer 1758, there were four raids on the Lunenburg Peninsula. On July 13, 1758, one person on the LaHave River at Dayspring was killed. Another was badly wounded by a member of the Labrador family. The next raid was at Mahone Bay, Nova Scotia on August 24, 1758. Eight Mi'kmaq attacked the homes of Lay and Brant families. Two days later, two soldiers were killed in a raid on the blockhouse at LaHave, Nova Scotia. Almost two weeks later, on September 11, a child was killed in a raid on the Northwest Range. Another raid happened on March 27, 1759. Three members of the Oxner family were killed. The last raid happened on April 20, 1759. The Mi'kmaq killed four settlers at Lunenburg. They were from the Trippeau and Crighton families.

Raids on Halifax (1757-1759)

Acadian Pierre Gautier led Mi'kmaq warriors from Louisbourg. They made three raids against Halifax in 1757. In each raid, Gautier took prisoners. The last raid was in September. Gautier and four Mi'kmaq killed two British men at the bottom of Citadel Hill. (Pierre later fought in the Battle of Restigouche.)

Four companies of Rogers' Rangers (500 rangers) arrived in Dartmouth. They were there from April 8 to May 28. They were waiting for the siege of Louisbourg. While there, they searched the woods to stop raids on the capital. Despite the Rangers, in April, the Miꞌkmaq returned 7 prisoners to Louisbourg. In July 1759, Mi'kmaq and Acadians killed five British in Dartmouth, across from McNabb's Island.

Siege of Louisbourg (1758)

Acadian fighters helped defend Louisbourg in 1757 and 1758. For a British attack on Louisbourg in 1757, all tribes of the Wabanaki Confederacy were there. This included Acadian fighters. Their efforts did not work. So, fewer Mi'kmaq and Acadians showed up the next year. This had happened before. In the two attacks on Annapolis, fewer Mi'kmaq and Acadians appeared for the second attack after the first failed.

New Englanders landed at Pointe Platee (Flat Point) during the 1745 siege. In 1757 and 1758, Native and Acadian fighters were at the possible landing beaches. These were Pointe Platee and Anse a la Cormorandiere (Kennington Cove).

In the siege of Louisbourg, Acadian and Mi'kmaq fighters started arriving around May 7, 1758. By the end of the month, 118 Acadians arrived. About 30 Mi'kmaq came from Ile St. Jean and Miramachi. Boishebert arrived in June with 70 more Acadian fighters from Isle Saint-Jean and 60 Mi'kmaq fighters. On June 2, British ships arrived. The fighters went to their defense spots on the shore. The 200 British ships waited six days for good weather. Then they attacked on June 8.

Four companies of Rogers' Rangers led by George Scott were the first to land. They were ahead of James Wolfe. The British landed at Anse de la Cormorandiere. "Continuous fire was poured upon the invaders." The Mi'kmaq and Acadian fighters fought the Rangers. Then Scott and James Wolfe's help arrived. This made the fighters retreat. Seventy of the fighters were captured. The Mi'kmaq and Acadian fighters killed 100 British. Some were wounded and drowned. On June 16, 50 Mi'kmaq returned to the cove. They took 5 seamen captive. They fired at other British marines.

On July 15, Boishebert arrived with Acadian and Mi'kmaq fighters. They attacked Captain Sutherland and the Rogers' Rangers at Northeast harbor. When Scott and Wolfe's help arrived, 100 Rangers were sent to find them. They only captured one Mi'kmaq. (From here, the Rangers went on to the St. John River campaign. They hoped to capture Boishebert.)

Battle at St. Aspinquid's Chapel

Stories say that at St. Aspinquid's Chapel in Point Pleasant Park, Halifax, Lahave Chief Paul Laurent and eleven others invited Shubenacadie Chief Jean-Baptiste Cope and five others to talk peace with the British. Chief Paul Laurent had just arrived in Halifax. He had surrendered to the British at Fort Cumberland on February 29, 1760. In early March 1760, the two groups met and fought. Chief Laurent's group killed Cope and two others. Chief Cope's group killed five of the British supporters.

Soon after Cope's death, Mi'kmaq chiefs signed a peace treaty in Halifax on March 10, 1760. Chief Laurent signed for the Lahave tribe. A new chief, Claude Rene, signed for the Shubenacadie tribe. During this time of surrender and treaty making, there were tensions among the groups allied against the British. For example, a few months after Cope's death, Mi'kmaq and Acadian fighters decided to keep fighting in the Battle of Restigouche. This was even though French priests encouraged surrender.

Battle of Restigouche

Acadian and Mi'kmaq fighters, totaling 1500, organized for the Battle of Restigouche. The Acadians arrived in about 20 schooners and small boats. With the French, they went upriver. They wanted to draw the British fleet closer to Pointe-à-la-Batterie. There, they were ready to surprise attack the English. The Acadians sank some of their ships to create a blockade. The Acadians and Mi'kmaq fired at the British ships.

On June 27, the British managed to get past the sunken ships. Once the British were in range, they fired on the battery. This fight lasted all night. It was repeated with breaks from June 28 to July 3. Then the British took over Pointe à la Batterie. They burned 150 to 200 buildings in the Acadian village.

The fighters retreated and joined the French frigate Machault. They sank more schooners to create another blockade. They built two new batteries. One was on the South shore at Pointe de la Mission (now Listuguj, Quebec). The other was on the North shore at Pointe aux Sauvages (now Campbellton, New Brunswick). They created a blockade with schooners at Pointe aux Sauvages. On July 7, British commander Byron spent the day removing the battery at Pointe aux Sauvages. Later, he returned to destroying the Machault. By the morning of July 8, the Scarborough and the Repulse were close to the blockade. They faced the Machault. The British tried twice to defeat the batteries, and the fighters held out. On the third try, they succeeded.

Halifax Treaties

The Mi'kmaq signed a series of peace and friendship treaties with Great Britain. The first was after Father Rale's War (1725). The Mi'kmaq nation had seven districts. Later, Great Britain was added as an eighth district in a ceremony during the 1749 treaty.

Chief Jean-Baptiste Cope signed a Treaty of 1752 for the Shubenacadie Mi'kmaq. After agreeing to several peace treaties, 75 years of war ended. This was with the Halifax Treaties between the British and the Miꞌkmaq (1760-1761). Nova Scotians celebrate Treaty Day on October 1 each year to remember these treaties. Even with the treaties, the British kept building forts in the province.

Historians have different ideas about what the Treaties mean. Stephen Patterson says the Halifax Treaties brought lasting peace. He believes the Mi'kmaq gave up fighting and chose to use British courts. Patterson says the Mi'kmaq were not militarily strong after the French were defeated. He argues that without guns and ammunition, the Mi'kmaq could not fight or hunt. So, the British could set the terms of the Treaties. Patterson says the Halifax Treaties defined the relationship between the Mi'kmaq and British. The Treaties did not say specific laws about land and resources. But they made sure both sides would follow future laws on these matters. The British accepted that Miꞌkmaw governments would continue to exist under British rule.

Historian John G. Reid disagrees with the Treaties saying the Mi'kmaq "submitted" to the British. He believes the Mi'kmaq wanted a friendly and equal relationship. He bases this on what was said during the talks and later Mi'kmaq statements. The Mi'kmaq leaders in the 1760 Halifax talks had clear goals. They wanted peace, fair trade for furs, and ongoing friendship with the British. In return, they offered friendship and allowed some British settlement. But they did not formally give up land. Reid argues that for true equality, any new British settlement needed to be negotiated. It also needed to include giving gifts to the Mi'kmaq. Europeans had a long history of giving gifts to Mi'kmaq to settle on their land. The peace agreements did not set clear land limits for British settlements. But they promised the Mi'kmaq access to natural resources. These resources had long supported them along the coasts and in the woods. Their ideas about land use were very different. The Mi'kmaq believed they could share the land. The British could grow crops, and the Mi'kmaq could hunt and get seafood as usual.

American Revolution (1775–1783)

More New England Planters and United Empire Loyalists arrived in Mi'kmaki (the Maritimes). This put pressure on the Mi'kmaq's economy, environment, and culture. The spirit of the treaties was lost. The Mi'kmaq tried to enforce the treaties by threatening force.

At the start of the American Revolution, many Mi'kmaq and Maliseet tribes supported the Americans. They were against the British. The Treaty of Watertown was the first foreign treaty signed by the United States. It was signed on July 19, 1776, in Watertown. This treaty created a military alliance. It was between the United States and the St. John's and Mi'kmaq First Nations in Nova Scotia. These were two groups of the Wabanaki Confederacy. They allied against Great Britain during the American Revolutionary War. (These Mi'kmaq delegates did not officially represent the Miꞌkmaw government. But many individual Mi'kmaq did join the Continental army.)

Months after signing the treaty, they fought in the Maugerville Rebellion. They also fought in the Battle of Fort Cumberland in November 1776.

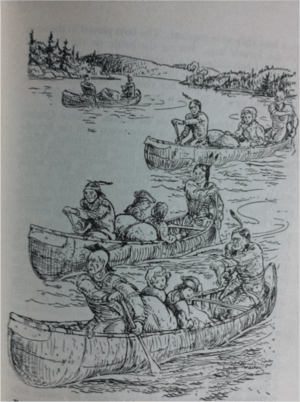

During the St. John River expedition, Colonel Allan worked hard. He wanted the Maliseet and Mi'kmaq to support the Revolution. He had some success. Many Maliseet left the St John River to join American forces at Machias, Maine. On Sunday, July 13, 1777, a group of 400 to 500 people left in 128 canoes. They went from the Old Fort Meduetic to Machias. The group arrived at a very good time for the Americans. They helped a lot in defending Machias during the attack by Sir George Collier on August 13–15. The British did little damage. The Native people's help earned them thanks from the Massachusetts council.

In June 1779, Mi'kmaq in the Miramichi attacked and robbed some British in the area. The next month, British Captain Augustus Harvey arrived. He commanded HMS Viper. He fought with the Mi'kmaq. One Mi'kmaq was killed. Sixteen were taken prisoner to Quebec. The prisoners were later brought to Halifax. They were released after signing an Oath of Loyalty to the British Crown on July 28, 1779.

1800s: A Time of Change

The Mi'kmaq's military power became weaker in the early 1800s. They asked the British to honor the treaties. They reminded the British of their duty to give "presents" (like rent) to the Mi'kmaq. This was for occupying Mi'kma'ki. The British offered charity, or "relief." The British told the Mi'kmaq they must change their way of life. They said they should settle on farms. They also said children had to go to British schools.

1900s: Joining Canada's Wars

In 1914, over 150 Mi'kmaq men joined up for World War I. During the war, 34 out of 64 Mi'kmaq men from Lennox Island First Nation, Prince Edward Island, joined the armed forces. They fought well, especially in the Battle of Amiens. On March 11, 1916, James Glode of Liverpool River was the first Mi'kmaq to join the war. In 1939, World War II began. Over 250 Miꞌkmaq volunteered. In 1950, over 60 Miꞌkmaq joined to serve in the Korean War.

The Treaties, which the Mi'kmaq fought for during the colonial period, became legal. They were put into the Canadian Constitution in 1982. Every October 1, "Treaty Day" is now celebrated by Nova Scotians.

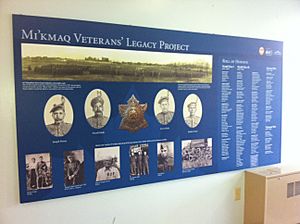

Notable Mi'kmaq Veterans

- Jean-Baptiste Cope

- Paul Laurent

- Étienne Bâtard

- Indian Joe

- Sam Gloade (born April 20, 1878), World War I, awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal, the British War Medal and the Victory Medal

See also

- Military history of Nova Scotia

- Military history of the Maliseet

- Military history of the Acadians

| Roy Wilkins |

| John Lewis |

| Linda Carol Brown |