Samuel Shute facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

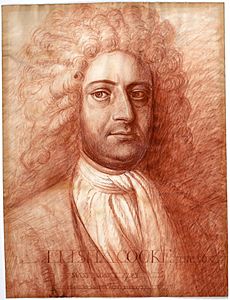

Samuel Shute

|

|

|---|---|

| 5th Governor of the Province of Massachusetts Bay | |

| In office October 5, 1716 – January 1, 1723 |

|

| Preceded by | William Tailer (Acting) |

| Succeeded by | William Dummer (Acting) |

| Governor of the Province of New Hampshire | |

| In office October 5, 1716 – January 1, 1723 |

|

| Preceded by | George Vaughan (Acting) |

| Succeeded by | John Wentworth (Acting) |

| Personal details | |

| Born | January 12, 1662 London, England |

| Died | April 15, 1742 (aged 80) England |

| Alma mater | Leiden University |

| Signature | |

Samuel Shute (born January 12, 1662 – died April 15, 1742) was an English military officer. He later became the royal governor for the areas of Massachusetts and New Hampshire. After fighting in two major wars, King George I chose him to be governor in 1716.

His time as governor was full of strong disagreements with the Massachusetts assembly. He also had trouble dealing with the Wabanaki Confederacy, a group of Native American tribes in northern New England. These problems eventually led to a conflict known as Dummer's War (1722–1725).

Even though Shute played a part in the breakdown of talks with the Wabanakis, he went back to England in 1723. He wanted to find solutions to his ongoing arguments with the Massachusetts assembly. He left William Dummer, the Lieutenant Governor, in charge of the war. Shute's efforts in England led to the Explanatory Charter in 1725. This document mostly supported his side in the disputes with the assembly. He never returned to New England. William Burnet replaced him as governor in 1728.

Contents

Early Life and Military Career

Samuel Shute was born in London, England, on January 12, 1662. He was the oldest of six children. His father, Benjamin Shute, was a merchant in London. Samuel's mother was the daughter of Joseph Caryl, a religious leader who was a Dissenter (meaning he didn't follow the main Church of England). His brother, John, later became an important member of Parliament.

Shute went to school with Rev. Charles Morton. Morton later moved to New England. Shute then studied at Leiden University in Holland. After that, he joined the English army and served under King William III.

During the War of the Spanish Succession, Shute fought with the Duke of Marlborough's army. He was a captain when he was hurt at the Battle of Blenheim in 1704. By the end of the war, he had become a Lieutenant Colonel and then a Colonel.

In 1714, King George I became king. Colonel Elizeus Burges was chosen to be the new Governor of Massachusetts and New Hampshire. However, people from Massachusetts, Jeremiah Dummer and Jonathan Belcher, paid Burges to resign before he even left England. Dummer and Belcher then helped Shute get the job. They thought he would be a good choice because he came from a respected Dissenting family.

Governor of Massachusetts and New Hampshire

Shute arrived in Boston on October 4, 1716. His time as governor was difficult and full of arguments. He showed his loyalty to one side right away by staying with Paul Dudley. Dudley was the son of the previous governor and was against a certain financial plan. Shute did not stay with the acting governor, William Tailer.

Governing New Hampshire

Shute's time in New Hampshire was less troubled than in Massachusetts. However, problems started early. Lieutenant Governor George Vaughan had been acting as governor for a year before Shute arrived. Vaughan insisted he had full power when Shute was not in New Hampshire. Against Shute's direct orders, Vaughan closed the assembly and fired a council member, Samuel Penhallow.

In September 1717, Shute, with his council's agreement, suspended Vaughan. He then called the assembly back and brought Penhallow back into his role. Vaughan was later officially replaced by John Wentworth as lieutenant governor.

One good thing that happened during Governor Shute's time was the arrival of many Scottish immigrants from Ireland. In 1718, Reverend William Boyd came from Ulster to ask for land for Presbyterian families who wanted to move. Shute welcomed him, and several ships with migrants arrived in August 1718. They settled in New Hampshire and founded the town of Londonderry. This was the start of many Scottish-Irish people moving to both New Hampshire and Massachusetts.

Shute also gave out land in what is now New Hampshire. However, much of southwestern New Hampshire was disputed between the two areas Shute governed. The land he gave out in that area went to people from Massachusetts. This made many New Hampshire politicians unhappy, especially Lieutenant Governor Wentworth. Wentworth used this unhappiness to gain power. This eventually led to the two governorships being separated after his death.

Disputes with Massachusetts Assembly

Shute had many arguments with the Massachusetts General Court (the local assembly). These arguments were about the king's power and other issues. During his time, the assembly gained more power, which changed how future governors and the assembly would interact until the colonies became independent. Money was a big issue that divided the area. One group wanted to print more paper money, which would cause prices to rise. Other powerful groups had different ideas for dealing with money problems.

A main opponent of Shute was Elisha Cooke Jr.. He was a politician and a large landowner in Maine, which was then part of Massachusetts. Cooke disagreed with Shute about money and about logging in Maine. During the previous governor's time, logging companies often ignored the 1711 White Pine Act. This British law said that large trees on public lands were reserved for the government to use as ship masts. Shute tried to stop this illegal logging, which made Cooke and others angry.

Cooke first challenged the law legally, but soon his actions became political. In 1718, the assembly chose Cooke to be on the Governor's Council, but Shute said no. Then, in 1720, the assembly chose Cooke to be its speaker. This started a big argument about the governor's powers. Shute refused to accept Cooke's appointment, saying he had the right to veto it. The assembly refused to choose anyone else. The next year, they chose a different speaker without telling Shute first.

Shute also argued with the assembly about its right to take short breaks. The governor was the only one who could officially call the assembly into session and end it. This was one way the governor could control the assembly. Shute disagreed with the assembly taking a six-day break. This argument, along with his refusal to approve Cooke, made the assembly strongly oppose Shute on almost everything. They even refused to give money to improve defenses on the northern and eastern borders, where there were problems with the Wabanaki Confederacy.

One of Shute's most famous arguments was about the assembly refusing to give him a regular salary. This was a common problem. When Shute vetoed Cooke's appointment in 1719, his salary was cut. The salary issue continued to be a regular disagreement between the assembly and the governor for many years. Shute tried to stop newspapers from printing things that criticized his policies. However, the assembly refused to pass the law he wanted, which helped establish freedom of the press in the area. Some religious leaders in Boston also didn't like that he went to Anglican church services. They also disliked his sometimes loud parties.

Native American Policy and Conflict

When the War of the Spanish Succession ended in 1713, the fighting in North America (known as Queen Anne's War) stopped. The Treaty of Utrecht that ended the war did not recognize any Native American land claims. It also had unclear language about France giving up Acadia. The disputed areas in northern New England included parts of modern-day Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and eastern Maine.

In 1713, Governor Joseph Dudley had made a peace agreement with the tribes in Massachusetts and New Hampshire. However, the written Treaty of Portsmouth was different from what was agreed upon verbally. British settlements were moving onto Abenaki lands in Maine, which broke the treaty's terms. Also, the Mi'kmaq tribe in Nova Scotia had not signed any treaties. Both France and Britain claimed to rule over the tribes in the disputed area. The tribes, who were part of the Wabanaki Confederacy, said they owned the land and were independent.

In 1717, Shute met with representatives of some Wabanaki tribes in Arrowsic, Maine. They tried to agree on colonial settlements on Native lands and the creation of trading posts run by the province. The Kennebec sachem (chief) Wiwurna objected to settlements and forts on their lands. He said they had control over those lands. Shute often interrupted Wiwurna rudely and simply repeated that the British claimed the territory. The Wabanakis were willing to accept existing settlements if a clear border was drawn. Shute replied, "We desire only what is our own, and that we will have." This unclear answer, and the treaty they eventually agreed to, did not satisfy the Wabanakis.

Over the next few years, settlers continued to move onto Wabanaki lands east of the Kennebec River. They even built block houses (small forts) on the east side of the river. The Wabanakis responded by raiding livestock. Canso, Nova Scotia, a settlement claimed by all three groups but mostly used by Massachusetts fishermen, also saw conflict. After hearing complaints from Canso fishermen in 1718, Shute sent a Royal Navy ship to the area. It seized French ships and goods. Tensions grew even more when the Mi'kmaq attacked Canso in 1720.

At a meeting in 1720, the Wabanakis agreed to pay 400 fur pelts for damage done in Maine. They left four hostages as a promise until the furs were delivered. Shute also complained about the French priest Sebastian Rale, who lived among the Kennebec in central Maine. Shute demanded that Rale be removed. In July 1721, the Wabanakis delivered half the furs and asked for their hostages back. They refused to hand over Rale, who was with them at the meeting. Massachusetts did not officially respond, and raids soon started again.

The Wabanakis then wrote a document stating their claims to the disputed areas. They listed the lands they claimed and threatened violence if their territory was entered. Shute called the letter "rude and threatening." He sent militia forces to Arrowsic. He also claimed that the Wabanaki's demands were part of a French plan to expand French claims. Following this idea, he sent a militia group to capture Rale in January 1722. The force reached the Kennebec village at Norridgewock, where Rale lived, but the priest escaped. The militia found a box with his papers, which included letters with French officials. Shute used these papers to show French involvement.

Shute repeated British claims of control over the disputed areas in letters to British officials and to Governor General Philippe de Rigaud Vaudreuil of New France. Vaudreuil replied that while France claimed control over the area, the Wabanakis still owned the land. He suggested that Shute did not understand how European and Native American ideas of ownership were different.

The raid on Norridgewock and the forts on the Maine coast caused a predictable response. The Wabanakis went to war, raiding British settlements on the Maine coast in 1722. They also seized ships off Nova Scotia. On July 25, 1722, Shute officially declared war on the Wabanakis. This marked the formal start of the conflict often called Dummer's War. Lieutenant Governor William Dummer ended up leading Massachusetts' involvement in the war.

Decision to Leave

Under the leadership of Cooke and others, the assembly looked into the province's spending. They found that some payments to the militia had been made dishonestly. The assembly then created spending bills that very carefully explained how public money could be used. This gave the assembly more power and reduced the governor's power. The assembly further took power from the governor by creating a committee to oversee the militia in December 1722. With the Native American war starting, Shute saw this as a serious threat to his authority. He decided that only by returning to London could he fix the situation. Soon after Christmas 1722, Shute sailed for England.

Later Years and Legacy

When Shute arrived in London, he presented his many problems to the Privy Council. His opponents were represented by Jeremiah Dummer and Elisha Cooke. Dummer had been a colonial agent in London for a long time, and Cooke was chosen by the assembly to present their side. The council agreed with Shute's arguments. Only Dummer's careful diplomacy convinced the council not to take away the colony's charter (its right to govern itself).

In 1725, the council issued an Explanatory Charter. This document supported Shute's position on the assembly's right to adjourn and the approval of the house speaker. The provincial assembly reluctantly accepted it the next year. Shute was getting ready to return to Massachusetts in 1727 when King George I died. This led to changes in London and new appointments for colonial governors. The Massachusetts and New Hampshire governorships were given to William Burnet, who was then the governor of New York and New Jersey. Shute was given a pension (regular payments).

Burnet's short time as governor was mostly spent trying to get a yearly salary. Burnet's sudden death in 1729 again opened the Massachusetts and New Hampshire governor positions. Shute was considered for the job again, but he declined. He instead supported Jonathan Belcher, who was actively seeking the position.

Shute never married. He died in England on April 10, 1743. The town of Shutesbury, Massachusetts is named in his honor.

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |