William Burnet (colonial administrator) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

William Burnet

|

|

|---|---|

Portrait by John Watson

|

|

| Governor of the Province of New York | |

| In office 1720–1728 |

|

| Monarch | |

| Preceded by | Peter Schuyler (acting) |

| Succeeded by | John Montgomerie |

| 4º Governor of the Province of New Jersey | |

| In office 1720–1728 |

|

| Monarch | |

| Preceded by | Lewis Morris, President of Council |

| Succeeded by | John Montgomerie |

| 6th Governor of the Province of Massachusetts Bay | |

| In office 19 July 1728 – 7 September 1729 |

|

| Monarch | George II |

| Preceded by | William Dummer (acting) |

| Succeeded by | William Dummer (acting) |

| Governor of the Province of New Hampshire | |

| In office 19 December 1728 – 7 September 1729 |

|

| Monarch | George II |

| Preceded by | John Wentworth (acting) |

| Succeeded by | John Wentworth (acting) |

| Personal details | |

| Born | March 1687/8 The Hague, Netherlands |

| Died | 7 September 1729 (aged 41) Boston, Massachusetts Bay |

| Spouse | Anna Maria Van Horne |

| Signature | |

William Burnet (born March 1687/88 – died 7 September 1729) was a British government official and leader in the American colonies. He served as governor of New York and New Jersey from 1720 to 1728. Later, he became governor of Massachusetts and New Hampshire from 1728 to 1729.

William Burnet came from a powerful family. His godfather became William III of England shortly after William's birth. His father, Gilbert Burnet, later became an important church leader. William received an excellent education, even being taught by the famous scientist Isaac Newton.

Burnet loved learning and scientific studies throughout his life. He became a member of The Royal Society in 1705/6, a group for top scientists. He did not hold major government jobs until money problems and political friends helped him become governor of New York and New Jersey.

In New Jersey, his time as governor was mostly calm. However, he started a trend of accepting payments or benefits in exchange for approving new laws. In New York, he tried to stop the fur trade between Albany and Montreal. He wanted the colonies to trade directly with Native American tribes instead.

His time in New York also saw more arguments between wealthy landowners and merchants. Burnet usually sided with the landowners. After King George I died, King George II made Burnet governor of New Hampshire and Massachusetts.

His time in New Hampshire was not very important. But in Massachusetts, he had a big disagreement with the local assembly (like a colonial parliament) about his salary. He kept the assembly meeting for six months and even moved them out of Boston. This argument stopped other important colonial business. Burnet died in September 1729, seemingly from an illness he got after his carriage overturned in water.

Contents

William Burnet's Early Life

William Burnet was born in The Hague, a major city in the Dutch Republic (now the Netherlands). This happened in March 1687 or 1688. He was the first child of Mary (Scott) Burnet and Gilbert Burnet. His father was a leading religious scholar in the Dutch court of William, Prince of Orange. Prince William was also Burnet's godfather.

William's mother, Mary Scott Burnet, came from a rich Scottish family living in the Netherlands. Her marriage to Gilbert was seen as a true love match. William had six younger brothers and sisters, but only four lived past infancy.

Later in 1688, Prince William led an army to England in what was called the Glorious Revolution. William III and Mary II became the rulers of England. Burnet's father gave the speech at their coronation. He later became a Bishop and had a lot of influence in the English court during King William's rule. However, he lost favor when Queen Anne became queen in 1702.

Burnet's mother died from smallpox in 1698. Two years later, his father married her close friend, Elizabeth Blake. She was a kind stepmother to William and his siblings. All the children loved their father very much. When Gilbert died in 1715, William inherited a large part of his father's estate.

William was a very smart student, but he sometimes struggled with rules. He started at Oxford at age 13 but was asked to leave for not following rules. He then had private teachers, including Isaac Newton. He eventually became a lawyer. In 1712, he married Mary, the daughter of George Stanhope. They had one son before Mary died in 1717.

William Burnet's Love for Learning

Burnet's special education gave him a lifelong interest in science and math. Isaac Newton suggested him for membership in The Royal Society in 1705. He became a member in February 1705/6. He knew the mathematician Gottfried Leibniz. He also regularly wrote about science to James Logan, a merchant and politician from Philadelphia.

He shared his observations of the Grindelwald Glacier in Switzerland with the Royal Society. He also reported on unusual conjoined twins from Hungary he saw in The Hague in 1708. While he was governor of New York, he watched Jupiter's moons eclipse. These observations helped scientists figure out New York City's exact location. He felt a bit lonely for intellectual talks in New York. He briefly met a young Benjamin Franklin and encouraged his smart ideas.

Like his teacher Isaac Newton, Burnet also wrote about religion. In 1724, he secretly published a book called An Essay on Scripture Prophecy. In this book, he used numbers to interpret the Book of Daniel from the Bible. He believed that Jesus Christ would return to Earth in 1790.

Governor of New York and New Jersey

Burnet's connections to the royal court helped him get a job as a customs officer in Great Britain. He also invested a lot of money in the South Sea Company. When this company failed in 1720, he looked for better-paying jobs in the American colonies.

An opportunity came from his old friend, Robert Hunter. Hunter was the governor of New York and New Jersey. He returned to England in 1719 and wanted to leave those jobs. Both Hunter and Burnet had good connections with the ruling Whig government. So, they easily switched jobs.

Leading New Jersey

As governor of New Jersey, Burnet faced arguments about issuing "bills of credit" and getting a regular salary. Bills of credit were like paper money and helped pay for the colony's costs. Issuing too many of these bills could make them worth less compared to British money. Burnet was told not to allow too many bills unless certain rules were met.

In 1721, the assembly approved a bill for £40,000 in bills, backed by property. Burnet disagreed and closed the assembly. However, in 1723, he approved a similar law. In return, the assembly agreed to pay his salary for five years. Later, when the assembly used money from the bills in ways he did not approve, Burnet agreed to sign anyway. He received £500 for "extra expenses." This way of the assembly giving the governor money for his agreement became somewhat common in New Jersey.

Leading New York

In New York, Burnet supported the wealthy landowners. Based on their advice, he refused to hold new elections for the assembly. This kept an assembly loyal to him for five years. His relationship with the New York assembly got worse when new elections brought in more members who opposed him. These new members elected a speaker who was against Burnet.

Burnet tried to tax more things, like large land holdings. But the powerful landowners in the assembly stopped these efforts. Instead, they shifted the taxes to merchants. One tax on ships docking in New York led to more smuggling between New Jersey and New York.

Eight months after arriving in New York, in May 1721, Burnet married again. His new wife was Anna Maria Van Horne. She was related to Robert Livingston, a powerful New York landowner and one of Burnet's main advisors. They had four children. Anna Maria and their last child died shortly after its birth in 1727.

Trade Policies with Native Americans

One important part of Burnet's time in New York was his effort to make the colony stronger on the frontier. He also wanted to improve relations with the Iroquois people. The Iroquois controlled most of what is now upstate New York. Since the Iroquois made peace with New France in 1701, a busy trade had grown between New York merchants in Albany and French merchants in Montreal.

English goods were sold to French traders. These French traders then traded the goods for furs with Native American tribes in central North America. British leaders wanted to change this trade. They told Burnet to direct the trade through Iroquois lands instead of through Montreal. This would stop the Albany-Montreal trade.

Soon after arriving in New York, Burnet had the assembly pass a law banning the Albany-Montreal trade. This made merchants who traded with New France angry. These included Stephen DeLancey and other Albany merchants. Two outspoken merchants, Adolph Philipse and Pieter Schuyler, were on the governor's council. Burnet removed them in 1721.

The law was easy to get around. Merchants sent their goods through nearby Mohawks, who then carried them to and from Montreal. A stronger law to stop the trade was passed in 1722. These policies caused protests in New York and in London. British merchants argued that the ban was hurting trade with Europe.

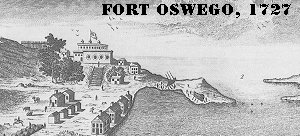

In 1723, Burnet learned that the French had started building Fort Niagara at the west end of Lake Ontario. This was a clear threat to British efforts to control the fur trade directly. So, he ordered the building of Fort Oswego at the mouth of the Oswego River.

This decision upset Albany traders, who would lose their control over the fur trade. It also upset the French because it gave the British direct access to Lake Ontario. The Iroquois were also unhappy. They had wanted a fort at Lake Oneida instead. Burnet tried to calm the Iroquois by placing soldiers in the Oneida area, but they did not like this either.

Burnet's attempts to change the trade policy did not work in the end. In 1725, the merchants, including Stephen DeLancey, won seats in the assembly. Burnet questioned if DeLancey, a Huguenot, was a citizen. This angered many moderate members of the assembly. In the following years, the assembly became much more against Burnet's rule.

The trade ban was removed in 1726. It was replaced by a tax system meant to favor trade to the west over the Albany-Montreal trade. By the time Burnet left in 1727, it was clear this new policy was also not working. All laws about Native American trade passed during his time were removed in 1729. The only lasting effects were the British military presence at Oswego and the end of Albany's trade control. Burnet also left New York more divided between merchants and landowners.

New Governor Takes Over

In 1727, King George I died. This meant that all royal appointments had to be renewed. King George II decided to give the New York and New Jersey governorships to Colonel John Montgomerie. Montgomerie had served the King closely. Burnet was instead appointed governor of Massachusetts and New Hampshire.

After people in New York learned Burnet would be replaced, the assembly protested his actions as a judge. They said his decisions would be invalid. This was a final jab from Stephen DeLancey. Montgomerie arrived in New York on April 15, 1728. Burnet left New York for Boston in July.

Governor of Massachusetts and New Hampshire

Burnet spent only a short time in New Hampshire. Unlike Massachusetts, he was quickly given a salary for three years or for as long as he was governor. When he was appointed to Massachusetts, the colony had been led for years by Lieutenant Governor William Dummer. Dummer was acting governor for Governor Samuel Shute.

Burnet tried very hard to make the Massachusetts assembly give him a permanent salary. Since the colony's royal charter began in 1692, the assembly had always refused this. Instead, they gave the governor money in small amounts over time. Local politicians found this a good way to influence the governor. They could make him approve their policies because he never knew when or how much money he would get next. The salary issue had bothered Governor Shute before Burnet. Dummer, who was from Massachusetts and wealthy, was more willing to compromise. He only insisted on keeping control of the colonial army.

Burnet took a very firm stand on the salary issue. He refused to do any other business or close the assembly until the salary was decided. The assembly, in turn, refused to pass a salary bill. They offered large one-time payments, but Burnet refused them on principle. He also suggested that if the assembly did not act, it might put the colony's charter at risk.

To make things harder for the lawmakers, Burnet moved the assembly from Boston. First, he moved them to Salem, and then to Cambridge. This increased the costs for the lawmakers and forced many of them away from their homes in the Boston area. In November 1728, the assembly voted to send representatives to London to argue their side to the Board of Trade. Their attempts to get money for these representatives were blocked by the governor's council. So, the representatives were paid with money raised by public donations.

In May 1729, the Board of Trade ruled in favor of Governor Burnet. But the assembly still refused to give in. Attempts to handle other matters always got stuck because of the salary dispute. The argument was still going on when Burnet was traveling from Cambridge to Boston on August 31. His carriage accidentally overturned, and he fell into the water. He became ill and died on September 7, 1729. He was buried in the King's Chapel Burying Ground in Boston.

Lieutenant Governor Dummer again acted as governor until Burnet's replacement was chosen. This replacement was Jonathan Belcher, one of the representatives who had been sent to London. Belcher took a similar stance as Burnet, refusing annual payments. He was later replaced as acting governor by William Tailer, who agreed to annual payments. Jonathan Belcher became governor later in 1730. At first, he was given the same instructions as Burnet about the salary. But during his time, the Board of Trade finally gave up on the instruction. They allowed him to receive annual payments.

Images for kids

| Jewel Prestage |

| Ella Baker |

| Fannie Lou Hamer |