South Sea Company facts for kids

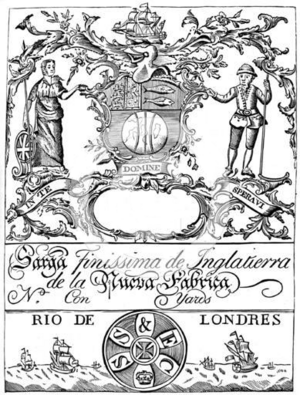

The South Sea Company's official symbol, showing a globe, fish, and the British royal arms.

|

|

| Public | |

| Industry | Slave trade, Speculation, Whaling |

| Founded | January 1711 |

| Defunct | 1853 |

| Headquarters |

,

Great Britain

|

The South Sea Company was a British company started in January 1711. It was set up to help the British government manage its large national debt. Think of it as a way for the government to get its finances in order.

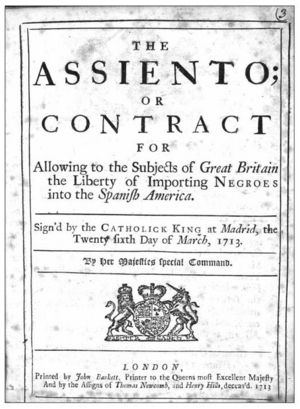

To make money, the company was given a special right in 1713. This right, called the Asiento de Negros, allowed them to be the only company to supply African slaves to Spanish colonies in the "South Seas" (which meant South America and nearby islands). However, Britain was at war with Spain at the time, so actual trade was very difficult. The company never made much money from this slave trade.

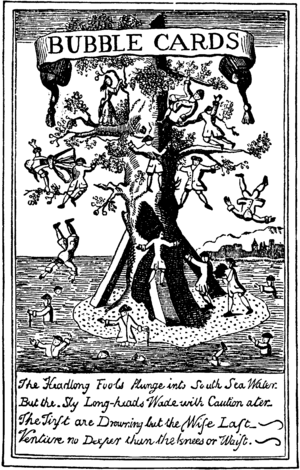

Even without much real trade, the company's shares became very popular. Their value grew a lot, especially in 1720. But then, suddenly, the share price crashed! This huge financial disaster, which ruined thousands of investors, became known as the South Sea Bubble.

Before the crash, the South Sea Company even pushed for a law called the Bubble Act in 1720. This law made it harder for other companies to form without special permission, which helped the South Sea Company for a short time.

Many people in Britain lost all their money when the shares collapsed. The country's economy suffered a lot. It turned out that the company's founders had used secret information to make huge profits for themselves. They also gave large bribes to politicians to get laws passed that helped their scheme. The company even used its own money to buy its shares, making the price seem higher than it was. They talked up the idea of huge profits from trade with South America to get people to buy shares, but the prices became much higher than what the company's real business (the slave trade) could ever support.

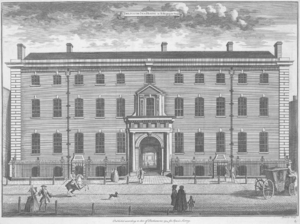

After the bubble burst, a government investigation found a lot of wrongdoing. Some politicians lost their jobs and their reputations. People who had made unfair profits had their money taken away. Even after all this, the South Sea Company was reorganized and continued to operate for over a century. Its main office was in Threadneedle Street in the financial heart of London. The crash also helped the Bank of England become the main bank for the British government.

Contents

How the Company Started

In 1710, a man named Robert Harley became in charge of the government's money. At that time, the government relied heavily on the Bank of England for loans. Harley wanted to find new ways to improve Britain's finances.

Britain was fighting two wars: the War of the Spanish Succession and the Great Northern War. These wars were very expensive. Harley showed Parliament how much debt the government had. The debt was a mess, with different government departments borrowing money on their own. In January 1711, Parliament decided to investigate all the debt.

Harley's first goal was to find money to pay the British army. Private banks and groups helped provide this money. The government also ran lotteries to raise funds. One lottery in 1711, managed by John Blunt, was very successful. This success led to an even bigger lottery called "The Two Million Adventure." Winners of this lottery received their prizes over several years, which meant the government kept the money for longer.

The Idea for the Company

The investigation found that the government owed about £9 million. There was no clear plan to pay this back. Robert Harley and John Blunt came up with a plan: a new company, the South Sea Company, would take over this debt. People who owned government debt would exchange it for shares in the new company.

In return, the government would pay the South Sea Company about £568,279 each year. This money would then be given to the shareholders as a dividend (a payment from the company's profits). The company also got the special right to trade with South America. This seemed like a great opportunity, but Spain controlled most of South America, and Britain was at war with Spain.

The idea for this company originally came from William Paterson, who helped start the Bank of England. Harley was rewarded for his plan by being made Earl of Oxford and becoming the Lord High Treasurer. He then started secret peace talks with France.

Early Excitement

Before the plan was public, government debts were worth less than their original value. But once the South Sea Company plan was announced, these debts would be worth their full value again. This meant that people who knew about the plan early could buy the old debts cheaply and then exchange them for valuable South Sea shares, making a quick profit. This possibility attracted many rich investors to the scheme.

The people who started the company knew there wasn't much money for real trading, and actual trade with South America was unlikely. But they made sure to tell everyone about the huge potential for wealth. Their main goal was to create a company that would make them rich and allow them to make more deals with the government.

Starting the Company

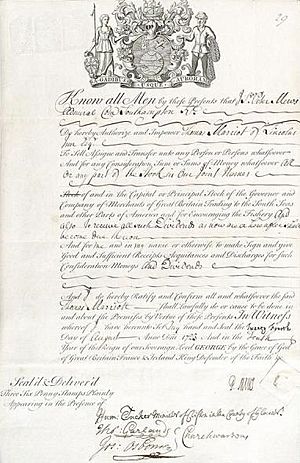

The official document for the company was created by John Blunt. The company would elect directors every three years, and shareholders would meet twice a year. The King of Britain would usually be the honorary Governor. Directors from the Bank of England and the East India Company could not be directors of the South Sea Company.

The government debt was exchanged for company stock in five stages. The first two stages, involving £2.75 million from about 200 big investors, were already set up before the company officially started in September 1711. The government itself exchanged £0.75 million of its own debt. Harley exchanged £8,000 of debt and became the company's Governor. Many important people, including politicians and financial leaders, became directors.

The company created its own coat of arms and rented a large building in London as its headquarters. The Hollow Sword Blade Company, which was like an unofficial bank, became the South Sea Company's banker.

The Slave Trade

In 1713, the Treaty of Utrecht gave Britain the Asiento de Negros for 30 years. This meant Britain had the right to supply 4,800 slaves each year to Spanish colonies. Britain could open offices in cities like Buenos Aires and Havana to arrange this trade. They were also allowed to send one ship (the Navío de Permiso) of general goods to these places each year. A quarter of the profits from this trade were supposed to go to the King of Spain.

By July 1713, the company made deals with the Royal African Company to get slaves from Jamaica. They paid £10 for a slave over 16 and £8 for those between 10 and 16. Most slaves were to be male adults. However, when the first slave shipments arrived, Spanish officials didn't accept the Asiento agreement right away. The slaves had to be sold at a loss in the West Indies.

Despite these problems, the company continued its slave trade. In 1714, they transported 2,680 slaves, and in 1716–1717, another 13,000. But this trade often didn't make a profit. There was also a tax of 33 "pieces of eight" on each slave. One of the extra trade ships sent to Cartagena in 1714 carried wool goods, which didn't sell for two years.

Historians believe the company transported over 34,000 slaves. The number of slaves who died during the journey was similar to other companies at the time. This shows that slave trading was a big part of the company's work, even if it wasn't always profitable.

Changes in Leadership

The South Sea Company depended a lot on the government's support. When the government changed, so did the company's leaders. In 1714, Robert Harley lost his job, and Queen Anne died. In 1715, the Prince of Wales (who later became King George II) was elected as the company's Governor. The new King George I and the Prince of Wales both owned many shares in the company. All the old Tory politicians were removed from the company's board and replaced with businessmen.

This change in government helped the company's share value, which had fallen. The previous government had not paid the company for two years, owing over £1 million. The new government made the company cancel this debt, but allowed them to issue new shares to make up for the missed payments. By 1714, the company had 2,000 to 3,000 shareholders, more than its rivals.

By 1718, politics changed again. The King became the Governor of the company. In 1718, the Sub-Governor and Deputy Governor both died, leaving the company without its most experienced leaders. They were replaced by Sir John Fellowes and Charles Joye.

War Affects Trade

In 1718, another war broke out with Spain. The South Sea Company's assets in South America were taken by the Spanish. The company claimed this cost them £300,000. Any hope of making profits from trade disappeared.

Government Debt and the Bubble

Events in France then influenced the South Sea Company. A Scottish economist named John Law had started a successful bank in France, which became the national bank. His success inspired the South Sea Company leaders to try to grow their own company even more.

In 1719, the government proposed a new plan to manage the national debt. The South Sea Company would take over more government debt. The government would pay the company 5% interest on this debt, which would save them money. The company could issue new shares for this debt. This conversion was voluntary for debt holders. The company also agreed to lend the government more money.

News from France about fortunes being made in Law's bank made people excited about investing. In July 1719, the South Sea Company announced its offer to the public. The company's share price rose from £100 to £114. About two-thirds of the government debt was exchanged for South Sea shares.

The 1719 plan was a big success for the government, so they wanted to do it again. Secret talks happened between government officials and the South Sea Company leaders. News from France continued to show huge profits from Law's bank, making people eager to invest.

Plans were made for the South Sea Company to take over most of Britain's remaining national debt, which was about £31 million. In exchange, the company would issue its shares. The government would pay the company the same amount of interest as before, but after seven years, the interest rate would drop. The company also agreed to give the government £3 million in cash. The more the company's share price rose before the debt was converted, the more profit the company would make.

The total government debt in 1719 was £50 million. The South Sea Company already held a large part of it. The goal was to turn government debt into shares that could be easily bought and sold. Shares backed by government debt were seen as a safe investment, much easier to trade than land or metal coins.

The government would get a cash payment and pay less interest on its debt. It also gained more control over when the debt had to be repaid. This helped the government avoid problems if it needed to borrow more money in the future. The money paid to the government would also be used to buy up any debt not included in the scheme, which helped the South Sea Company by removing competing investments from the market.

The company's stock was trading at £123. The new plan meant £5 million of new money would enter the economy, just as interest rates were falling.

Public Announcement

On January 21, the plan was shown to the South Sea Company's board. The next day, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, John Aislabie, presented it to Parliament. Parliament was surprised and asked the Bank of England to make a better offer. In response, the South Sea Company increased its cash payment to £3.5 million. The Bank of England offered £5.5 million. On February 1, the South Sea Company raised its offer again to £4 million, plus more depending on how much debt was converted. They also agreed that the interest rate would drop after four years instead of seven. Parliament accepted the South Sea Company's offer, and Bank of England shares fell sharply.

A first sign of trouble came when the South Sea Company delayed its Christmas 1719 dividend. The company then started to reward its friends. Important people were given company stock at the current price, but they didn't have to pay for it right away. They could sell the stock back to the company later and keep the profit from the price increase. This helped win over government leaders and the King's friends. By making these elite people shareholders, the company looked more trustworthy, which attracted more buyers.

The plan was officially accepted in April 1720. The South Sea Company managed to get 85% of the redeemable debts and 80% of the irredeemable annuities.

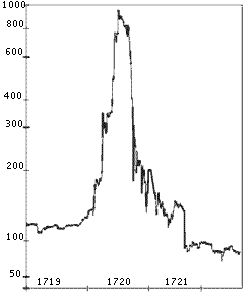

The company then started spreading "wild rumors" about how much money it would make from trade in the New World. This led to a huge wave of excitement and speculation. The share price jumped from £128 in January 1720 to £175 in February, £330 in March, and £550 by the end of May.

What might have helped the company's high value was the belief that it had £70 million in credit for business expansion, supposedly supported by Parliament and the King.

Shares were "sold" to politicians at the market price, but they didn't have to pay for them. They just held onto the shares and could sell them back to the company later for a profit. This made sure that these powerful people wanted the stock price to go up. By showing off its famous shareholders, the company seemed more legitimate, which attracted more investors.

The Bubble Act

The South Sea Company wasn't the only company trying to raise money in 1720. Many other companies, called "Bubbles," were created. They made wild claims about foreign ventures or strange schemes. Some of these companies had no legal right to exist.

On February 22, 1720, Parliament started an investigation into these "bubble" companies. They decided that companies should only operate within the rules of their official charters. The South Sea Company avoided trouble when its banker, the Hollow Sword Blade Company, was questioned. Supporters of the South Sea Company in Parliament voted against investigating it further.

The investigation led to the Bubble Act in June 1720. This law said that a company could only be officially formed by an Act of Parliament or a special royal permission. This law helped the South Sea Company by limiting its competitors. After the Act passed, the South Sea Company's shares jumped to £890 in early June.

The Peak and the Crash

The company's stock price went from about £100 to almost £1,000 per share in just one year. This success caused a huge craze across the country. Everyone, from farmers to lords, became obsessed with investing, especially in South Sea shares. There's a famous story about a company that went public in 1720 as "a company for carrying out an undertaking of great advantage, but nobody to know what it is."

The price finally reached £1,000 in early August 1720. But then, people started selling their shares, and the price began to fall. It dropped back to £100 per share before the end of the year. This caused many people who had bought shares with borrowed money to go bankrupt. More people started selling, even selling shares they didn't own, hoping to buy them back cheaper later.

Also, in August 1720, the first payments for new South Sea stock were due. Earlier, John Blunt had an idea to keep the price high: the company would lend people money to buy its shares. As a result, many shareholders couldn't pay for their shares unless they sold them.

The collapse also happened at the same time as similar "bubbles" burst in Amsterdam and Paris, including John Law's Mississippi Company in France. This made the South Sea share price fall even faster.

The Aftermath

By the end of September, the stock had fallen to £150. Many banks and goldsmiths failed because they couldn't get back the money they had lent for stock purchases. Thousands of people, including many rich and powerful individuals, were ruined.

Angry investors demanded action. Parliament met in December, and an investigation began. In 1721, the investigation found widespread fraud among the company's directors and corruption within the government. Many important politicians were involved, including the Chancellor of the Exchequer, John Aislabie. Some officials died in disgrace, and others were removed from office for corruption. Aislabie was found guilty of "notorious, dangerous and infamous corruption" and was put in prison.

Robert Walpole, who became the new First Lord of the Treasury, helped bring back trust in the financial system. Public opinion, especially from those who lost money, wanted revenge. Walpole oversaw the process that removed all 33 company directors and took away, on average, 82% of their wealth. This money went to the victims. The remaining South Sea Company stock was divided between the Bank of England and the East India Company. Walpole made sure the King and his friends were protected. He also managed to save several key government officials from being removed from office. Because of this, Walpole became a very powerful figure in British politics and is credited with saving the government from complete disaster.

Famous Quotes About the Crash

It is said that when Isaac Newton, the famous scientist, was asked about the rising South Sea stock, he replied: "I can calculate the movement of the stars, but not the madness of people." Newton himself owned a lot of South Sea stock and may have lost a large sum of money.

The Company's Real Trade

The South Sea Company was created in 1711 to help with government debts. But it was also given the special right to trade with the Spanish colonies in the Americas. This right came from a treaty signed in 1713, which gave Britain the right to the slave trade (the Asiento de Negros) for 30 years.

The company's board didn't really want to get into the slave trade because it hadn't been very profitable for other companies. But it was the only legal way to trade with the Spanish colonies, which were usually closed to foreign merchants. To make it more profitable, the Asiento contract also allowed one 500-ton ship each year, filled with tax-free goods, to be sold at markets in Spanish America. The King of England and the King of Spain were each supposed to get 25% of the profits. However, Queen Anne soon gave up her share. The King of Spain never received his payments, which caused problems between Spain and the company.

Like earlier companies that held the Asiento, the real profit wasn't just in the slave trade itself. It was in the illegal goods smuggled on the slave ships and the annual trade ship. These goods were sold at high prices in the Spanish colonies because they were in high demand. This illegal trade caused big losses for the Spanish government's own trade income.

The relationship between the South Sea Company and the Spanish government was always bad. The company complained about its goods being seized. Spain complained about the illegal trade and the company not paying the King's share of the profits. These arguments led to worse relations between the two countries. In 1739, a treaty was signed where Spain would pay British merchants for seized goods, and the South Sea Company would pay Spain for its share of profits. But the South Sea Company refused to pay. This breakdown in relations led to a war called the War of Jenkins' Ear, which started in 1739.

Slave Trade Under the Asiento

Spain was the only European power that couldn't set up slave trading posts in Africa. So, slaves for Spanish America were provided by companies that had special monopoly contracts, called the slave Asiento. From 1701 to 1713, France held this contract. In 1713, as part of the Treaty of Utrecht, Britain got the Asiento from France for the next 30 years.

The South Sea Company's directors were hesitant to take on the slave trade, as it wasn't their original purpose and hadn't been very profitable for other companies. But they finally agreed in March 1714. The Asiento set a quota of 4,800 slave units per year. An adult male slave counted as one unit.

The South Sea Company set up slave reception centers in various Spanish American cities, and slave holding areas in Jamaica and Barbados. Despite the financial speculation problems, the South Sea Company was quite successful at slave trading and often met its quota. Records show that over 96 voyages in 25 years, the company bought 34,000 slaves. About 30,000 of them survived the journey across the Atlantic, which was a relatively low death rate for the "Middle Passage." The company continued its slave trade even through two wars with Spain and the huge financial crash of 1720. The company's slave trade was busiest around 1725, five years after the bubble burst.

The Annual Ship

The 1713 slave Asiento contract also allowed one 500-ton ship per year, filled with tax-free goods, to be sold at markets in New Spain and other Spanish colonies. This was a big deal because it broke two centuries of strict rules keeping foreign merchants out of the Spanish Empire.

The first ship, the Royal Prince, was supposed to sail in 1714 but was delayed until August 1716. Only seven annual ships sailed during the Asiento period, with the last one being the Royal Caroline in 1732. The company failed to provide proper financial records for most of these trips and didn't pay the Spanish Crown its share of the profits. Because of this, no more permits were given for the company's ships after 1732.

Unlike the slave trade, the regular trade from these annual ships made good profits, sometimes over 100%. The South Sea Company never paid the Spanish Crown the money it owed from these trips. This lack of payment was a major reason for the bad relationship between the company and the Spanish government, which eventually led to war.

Arctic Whaling

In 1722, a proposal was made for the South Sea Company to start whaling in the Arctic. The British Parliament confirmed that British Arctic whaling would not have to pay customs duties. So, in 1724, the South Sea Company decided to start whaling. They built 12 whale-ships and sent them to the Greenland seas in 1725.

More ships were built later, but the whaling business was not successful. There were few experienced whalers left in Britain, so the company had to hire Dutch and Danish whalers for important jobs on their ships. Costs were not managed well, and they caught very few whales, even though the company sent up to 25 ships some years. By 1732, the company had lost £177,782 from its eight years of Arctic whaling.

The South Sea Company asked the British government for more help. In 1732, a law extended the tax-free benefits for nine more years. In 1733, another law gave government money to British Arctic whalers. Despite these benefits, the South Sea Company decided they couldn't make a profit from Arctic whaling. They stopped sending out whale-ships after the losing season of 1732.

Government Debt After the Seven Years' War

The South Sea Company continued its trade (when not interrupted by wars) until the end of the Seven Years' War (1756–1763). However, its main job was always managing government debt, not trading with Spanish colonies. The company continued to manage part of the national debt until it was officially closed down in 1853. At that point, the debt was reorganized again.

Company Symbols

The South Sea Company had its own official symbols, granted in 1711. Its shield showed a globe with the Straits of Magellan and Cape Horn, two herrings, and the British royal arms. Its crest was a ship with three masts. On either side, it had supporters: one was the symbol of Britannia (a woman representing Britain), and the other was a fisherman holding a string of fish.

Leaders of the South Sea Company

The South Sea Company had a Governor (usually an honorary position held by the King), a Subgovernor, a Deputy Governor, and 30 directors (later reduced to 21).

| Year | Governor | Subgovernor | Deputy Governor |

|---|---|---|---|

| July 1711 | Robert Harley, 1st Earl of Oxford | Sir James Bateman | Samuel Ongley |

| August 1712 | Sir Ambrose Crowley | ||

| October 1713 | Samuel Shepheard | ||

| February 1715 | George, Prince of Wales | ||

| February 1718 | King George I | ||

| November 1718 | John Fellows | ||

| February 1719 | Charles Joye | ||

| February 1721 | Sir John Eyles, Bt | John Rudge | |

| July 1727 | King George II | ||

| February 1730 | John Hanbury | ||

| February 1733 | Sir Richard Hopkins | John Bristow | |

| February 1735 | Peter Burrell | ||

| March 1756 | John Bristow | John Philipson | |

| February 1756 | Lewis Way | ||

| January 1760 | King George III | ||

| February 1763 | Lewis Way | Richard Jackson | |

| March 1768 | Thomas Coventry | ||

| January 1771 | Thomas Coventry | vacant (?) | |

| January 1772 | John Warde | ||

| March 1775 | Samuel Salt | ||

| January 1793 | Benjamin Way | Robert Dorrell | |

| February 1802 | Peter Pierson | ||

| February 1808 | Charles Bosanquet | Benjamin Harrison | |

| 1820 | King George IV | ||

| January 1826 | Sir Robert Baker | ||

| 1830 | King William IV | ||

| July 1837 | Queen Victoria | ||

| January 1838 | Charles Franks | Thomas Vigne |

In Stories

- The historical mystery novel A Conspiracy of Paper by David Liss is set in London in 1720. It focuses on the South Sea Company at its peak and the events leading to the "bubble" collapse.

- Famous author Charles Dickens often wrote about stock market schemes and dishonest people in his novels. Some examples include:

- Nicholas Nickleby (1839) features a fake company called the "United Metropolitan Improved Hot Muffin and Crumpet Baking and Punctual Delivery Company."

- Martin Chuzzlewit (1844) has a company called "Anglo-Bengalee Disinterested Loan and Life Company," which is similar to a Ponzi scheme and loosely based on the South Sea Bubble.

- Robert Goddard's novel Sea Change (2000) explores what happened after the "bubble" burst and how politicians tried to avoid blame.

See Also

In Spanish: Compañía del Mar del Sur para niños

In Spanish: Compañía del Mar del Sur para niños

- List of stock market crashes and bear markets

- SSC coinage

- Tulip mania

- History of company law in the United Kingdom

- Whaling in the United Kingdom

- Mississippi Bubble

- Buttonwood Agreement USA 1792

| Aurelia Browder |

| Nannie Helen Burroughs |

| Michelle Alexander |