Robert Walpole facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

The Earl of Orford

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Portrait by Jean-Baptiste van Loo, c. 1740

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister of Great Britain | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 3 April 1721 – 11 February 1742 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monarch | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Office established | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | The Earl of Wilmington | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| First Lord of the Treasury | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 4 April 1721 – 11 February 1742 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Charles Spencer | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | The Earl of Wilmington | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 10 October 1715 – 12 April 1717 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | The Earl of Carlisle | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | The Earl Stanhope | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chancellor of the Exchequer | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 3 April 1721 – 12 February 1742 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Sir John Pratt | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Samuel Sandys | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 12 October 1715 – 15 April 1717 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Sir Richard Onslow | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | The Earl Stanhope | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | 26 August 1676 Houghton, Norfolk, England |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 18 March 1745 (aged 68) London, England |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Resting place | St Martin at Tours' Church, Houghton, Norfolk, England | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Political party | Whig | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spouses |

Catherine Shorter

(m. 1700; died 1737)Maria Skerret

(m. 1738; died 1738) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | 6; including Robert, Edward and Horace | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Parent |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Relatives | Walpole family | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Education | Eton College | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alma mater | King's College, Cambridge | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Occupation |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Signature |  |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Robert Walpole, 1st Earl of Orford (born 26 August 1676 – died 18 March 1745), was a very important British politician. He is often seen as the first Prime Minister of Great Britain. He held powerful jobs like First Lord of the Treasury and Chancellor of the Exchequer.

Walpole was a member of the Whig Party. He was in charge of the government for a long time, from 1721 to 1742. This was a record 20-year period! Historians say he was very good at handling the political system. He knew how to balance the King's power with the growing influence of the House of Commons.

Walpole was a country gentleman who first became a Member of Parliament in 1701. He was known for his calm and convincing speeches. He aimed for peace, lower taxes, and more trade. He tried to avoid big arguments and kept a middle path. This helped him get support from both Whigs and Tories.

Many people see Walpole as one of Britain's greatest politicians. He helped the Whig party stay strong and kept the Hanoverian royal family on the throne. He also protected the ideas of the Glorious Revolution of 1688. He showed future leaders how to work well with both the King and Parliament.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Walpole was born in Houghton, Norfolk, in 1676. He was one of 19 children! His father, also named Robert Walpole, was a local gentleman and a Whig politician. His mother was Mary Burwell.

As a child, Robert went to a private school in Massingham, Norfolk. In 1690, he went to Eton College, a famous school. He then studied at King's College, Cambridge. He had planned to become a clergyman. However, his older brother died in 1698. This meant Robert became the oldest son and had to help manage the family's land. His father died in 1700, and Robert inherited the family estate.

Starting a Political Career

Early Business and First Steps in Politics

When he was young, Walpole bought shares in the South Sea Company. This company had a special right to trade with Spain and other places. Many people invested a lot of money in it. The company's shares went up very high, then crashed. This event was called the "South Sea Bubble." Luckily, Walpole sold his shares before the crash and made a lot of money. This helped him build his grand home, Houghton Hall.

Walpole's political journey began in January 1701. He won a seat in Parliament for Castle Rising. In 1702, he moved to represent King's Lynn, a place that kept electing him. People often called him "Robin."

Rising Through Government Roles

Like his father, Robert Walpole was a Whig. In 1705, Queen Anne made him a member of her husband's council. Her husband, Prince George of Denmark, was the Lord High Admiral. Walpole became known for helping the Whigs and the government work together.

In 1708, he became Secretary at War, a very important job. For a short time in 1710, he was also the Treasurer of the Navy.

However, the Whig party lost power in 1710. The new government, led by the Tory Robert Harley, removed Walpole from his jobs. Harley tried to get Walpole to join the Tories, but Walpole refused. He became a strong voice for the Whig opposition.

In 1712, Walpole faced accusations about some contracts for the army. He was found "guilty of a high breach of trust." He was sent to the Tower of London for six months and removed from Parliament. While in the Tower, many Whig leaders visited him. They saw him as a political hero. After his release, he wrote articles criticizing the government. He was re-elected to Parliament in 1713.

The Stanhope-Sunderland Government

Queen Anne died in 1714. George I became King. He did not trust the Tories. This led to the Whigs gaining power for the next 50 years. Robert Walpole became a Privy Councillor and was made Paymaster of the Forces. He also chaired a committee that looked into the previous Tory government's actions.

In 1716, Walpole became First Lord of the Treasury and Chancellor of the Exchequer. He introduced a "sinking fund" to help reduce the national debt. However, the government was often divided. Walpole and his brother-in-law, Charles Townshend, were on one side. James Stanhope and Charles Spencer were on the other. They disagreed a lot about foreign policy.

In 1717, Townshend was removed from a key job. The next day, Walpole resigned from the government. He said he "could not agree with some things that were happening." This caused a split in the Whig party for three years.

Walpole remained important in Parliament. He strongly opposed the "Peerage Bill." This bill would have limited the King's power to create new noble titles. Walpole helped stop this bill from passing. This made Stanhope and Spencer want to work with him again. Walpole returned to government as Paymaster of the Forces in 1720.

Becoming Prime Minister

The South Sea Bubble Crisis

Soon after Walpole returned, Britain faced a huge financial crisis called the South Sea Bubble. Many people had invested in the South Sea Company, hoping to get rich quickly. The company promised big profits from trade. But by late 1720, the company's shares crashed, and many people lost everything.

A committee looked into the scandal in 1721. They found that many government officials were involved in the corruption. Some were even sent to prison. Walpole helped protect some of his allies, like Stanhope and Sunderland, from being punished. Because of this, he was nicknamed "The Screen."

Walpole Takes Charge

After the crisis, Walpole became the most important person in the government. On 3 April 1721, he was made First Lord of the Treasury, Chancellor of the Exchequer, and Leader of the House of Commons. This is often seen as when he truly became the "prime minister," even though he didn't use that title himself. His brother-in-law, Lord Townshend, handled foreign affairs.

Walpole's government worked to fix the financial problems from the South Sea Bubble. They used the money from the company's directors to help those who had lost money. Walpole also defended the King and the Whig Party in Parliament.

In his first year, a plot by Bishop Francis Atterbury was discovered. This plot aimed to bring back the Jacobite royal family. Exposing the plot ended the hopes of the Jacobites.

During King George I's reign, Walpole's power grew. The King's power slowly decreased, and his ministers' power increased. In 1724, Lord Carteret, a rival, was moved to a less important job in Ireland.

Walpole helped keep Britain peaceful. He negotiated a treaty with France and Prussia in 1725. Britain was free from threats and financial problems, and the country became richer. Walpole gained the King's favor. In 1726, he was made a Knight of the Garter, a very high honor. This earned him the nickname "Sir Bluestring."

Leading Under King George II

Walpole's position was at risk when King George I died in 1727. His son, George II, became King. For a few days, it looked like Walpole would be fired. But Queen Caroline, the King's wife, advised George II to keep Walpole.

Walpole continued to share power with Townshend for a few years. But they disagreed about foreign policy, especially concerning Austria. Slowly, Walpole became the clear leader. Townshend retired in 1730. This is sometimes seen as the true start of Walpole's time as prime minister. Townshend's departure allowed Walpole to make a treaty with Austria.

Facing Opposition

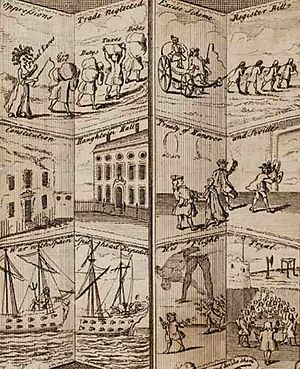

Walpole had many enemies. Some were in the Country Party, like Lord Bolingbroke and William Pulteney. These opponents wrote articles in a newspaper called The Craftsman, criticizing Walpole. He was also made fun of in plays and writings. Famous writers like Jonathan Swift and Alexander Pope were among his critics.

Gaining Support

Walpole kept the support of the people and Parliament by avoiding wars. He stopped King George II from joining the War of the Polish Succession in 1733. He famously said, "There are 50,000 men slain in Europe this year, and not one Englishman." By avoiding wars, he could lower taxes.

He reduced the national debt and lowered the land tax. His goal was to replace the land tax, paid by landowners, with taxes on goods like wine and tobacco. These "excise taxes" would be paid by merchants and consumers. However, his plan to tax wine and tobacco in 1733 was very unpopular. Many merchants opposed it. Walpole had to withdraw the bill. He then fired the politicians who had opposed him. This caused some Whigs to join the opposition.

After the 1734 election, Walpole still had a majority in Parliament, but it was smaller. In 1736, riots broke out in London because of a tax increase on gin. More serious riots happened in Edinburgh. Despite these problems, Walpole kept his majority in Parliament. He also passed the Licensing Act of 1737, which controlled London theaters. This act showed his dislike for the writers who attacked his government.

Walpole also paid writers and journalists to defend him. They argued that corruption was a part of human nature and that strong government was needed to control conflict.

Losing Power

In 1737, Walpole's close friend Queen Caroline died. While he still had King George II's loyalty, Walpole's power began to fade. His opponents found a new leader in the Prince of Wales, who did not get along with his father, the King. Young politicians like William Pitt the Elder joined the Prince of Wales in opposition.

Walpole's policy of avoiding war eventually led to his downfall. Under a treaty, Britain agreed not to trade with Spanish colonies. Spain claimed the right to search British ships. Disputes arose over trade in the West Indies. Walpole tried to avoid war, but the King, Parliament, and even some of his own government members wanted to fight. In 1739, Walpole gave in and started a war with Spain.

Walpole's influence continued to drop after the war began. In the 1741 election, his party lost many seats. His majority in Parliament became very small. Many Whigs felt he was too old to lead the war. People also accused him of corruption and getting rich in office.

In 1742, Walpole lost an important vote in the House of Commons. He agreed to resign from the government. The news of a naval defeat against Spain also pushed him to resign. King George II was sad to see him go. As part of his resignation, the King made him a noble, the Earl of Orford. This happened on 6 February 1742. Five days later, he officially left his government jobs.

Even after resigning, Walpole remained an important advisor to King George II. His former colleagues still sought his advice. He continued to support the government and speak for them in the House of Lords.

Later Life and Death

Lord Orford was replaced by Lord Wilmington as prime minister. A committee was formed to investigate Walpole's time in office, but they found no strong evidence of wrongdoing. Even though he was no longer in the government, Walpole still had personal influence with King George II. He was sometimes called the "Minister behind the Curtain" because of his advice. In 1744, he helped get rid of Lord Carteret and brought in Henry Pelham, whom he saw as a promising young politician.

In his last years, Walpole enjoyed hunting at his country home, Houghton Hall. He also loved his art collection, which he had built up over many years. He had collected many famous paintings from across Europe.

Walpole's health got worse in late 1744. He died in London on 18 March 1745, at 68 years old. He was buried at the Church of St Martin at Tours on his Houghton estate. His title passed to his eldest son, Robert.

Walpole's Legacy

Walpole had a huge impact on British politics. The Tories became a small party, and the Whigs became very powerful. He is seen as Britain's first prime minister, but his power came more from his personal relationship with the King than from his official job. It took many more decades for the prime minister's role to become the most powerful in the country.

Walpole's choice to keep Britain peaceful helped the country become rich. He also made sure the Hanoverian royal family stayed in power and stopped threats from the Jacobites. The Jacobite threat ended soon after Walpole left office.

10 Downing Street is another part of Walpole's legacy. King George II offered this house to Walpole as a gift in 1732. But Walpole accepted it only as the official home for the First Lord of the Treasury. He moved in on 22 September 1735. While his immediate successors didn't always live there, it became the official residence of the prime minister.

Walpole also helped British industry. He supported wool manufacturers with taxes on imports and other help. This made wool Britain's main export. It helped the country bring in raw materials and food, which were important for the Industrial Revolution.

Walpole is remembered in St Stephen's Hall in Parliament, where his statue stands.

His art collection, once one of the best in Europe, was sold to the Russian Empress Catherine the Great in 1779. These artworks are now in the State Hermitage Museum in Russia. In 2013, some of these artworks were loaned back to Houghton Hall for display.

The nursery rhyme "Who Killed Cock Robin?" might be about Walpole's fall from power. He was sometimes called "Cock Robin" by people at the time. His time in power was also nicknamed the "Robinocracy."

Some places are named after Walpole, like Walpole Street in Wolverhampton, England. Also, the towns of Walpole, Massachusetts (founded in 1724) and Orford, New Hampshire (started in 1761) in the United States.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Robert Walpole para niños

In Spanish: Robert Walpole para niños