Métis buffalo hunting facts for kids

The Métis people hunted buffalo on the North American plains from the late 1700s until 1878. These big buffalo hunts were super important for Métis families and communities. They provided food, helped with their way of life, and were even part of their economy and defense.

At the peak of the buffalo hunting time, there were two main hunting seasons: summer and autumn. These hunts were very well organized. They even had an elected council to lead the whole trip! This made sure everything was fair and that all families had enough food and supplies for the year.

Contents

What's in a Name? Buffalo or Bison?

Even though there are no true buffalo species native to the Americas, the Métis word for bison is lii bufloo. Bison are not the same as the true buffalo species found in other parts of the world. However, people have called American bison "buffalo" since 1616. That's when Samuel de Champlain used the French word buffles for them, after seeing skins and drawings from First Nations people who hunted them.

How the Hunts Started

Métis buffalo hunting began in the late 1700s. Trading companies on the plains needed food that could last a long time for their traders. Pemmican, a dried meat product, was perfect because it could be stored without spoiling.

The Métis started hunting buffalo to trade pemmican with these companies. In the early days, buffalo herds were close to the communities, so Métis families could hunt and trade on their own. But as more settlers and Métis arrived, the buffalo moved further away. The hunts then became much bigger and more organized to meet the growing demand and feed more people. Métis families started traveling together in large groups for safety.

The Great Buffalo Hunts

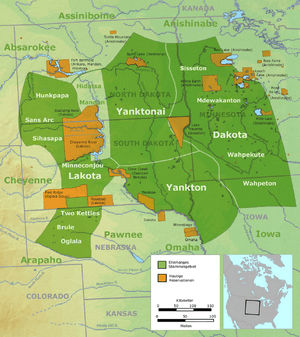

The Métis of the Red River Colony held buffalo hunts twice a year. The hunts from the Red River area had three main groups: the Pembina Métis, the St. Boniface Métis (also called the Main River party), and the St. Francois Xavier Métis. The St. Boniface Métis, living near the Red River of the North in what is now Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada, made up the largest part of these hunts. They had both a summer and an autumn hunt.

By the 1830s, every major hunt had a common way of organizing and a set of rules. The biggest hunts started about ten years later. For the summer hunts, the three groups would meet at Pembina to get organized before heading to the buffalo hunting grounds.

Everyone in the family helped with the hunt. The faster the buffalo meat was prepared and saved, the less likely it was to spoil in changing weather. Men usually did the hunting. Women were in charge of setting up and taking care of the camps, and preparing and preserving the buffalo meat. A successful hunt could bring in thousands of buffalo.

Summer Hunts: The Dried Meat Hunt

The summer buffalo hunt, also known as the dried meat hunt, usually happened from June to late July or early August. When the season began, the Métis would plant their crops in the spring. Then, they would set out with their wives and children, leaving a few people behind to look after the fields. The warm weather made this season perfect for making dried meat, pemmican, and buffalo tongue. The Métis often traded these products with the Hudson's Bay Company.

In 1840, the Red River settlement had over 4,800 people. Of these, 1,630 took part in the summer hunt and traveled south onto the Great Plains. The Métis from different Red River settlements often traveled in large groups for protection because they were sometimes bothered by the Sioux.

The buffalo hunts provided the Métis with an impressive organizational structure and by 1820 was a permanent feature of life for all individuals on or near the Red River and other Métis communities.

—Louis Riel Institute

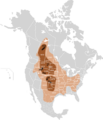

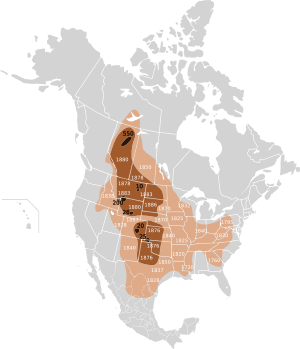

By 1879, hunters in Canada reported that only a few buffalo were left. Two years later, the last buffalo herds in the Montana Territory were also gone.

Paul Kane, an Irish-born Canadian painter, saw and joined the Métis buffalo hunt in 1846. Some of his paintings show scenes from this hunt in the Sioux lands of the Dakota Territory in the United States.

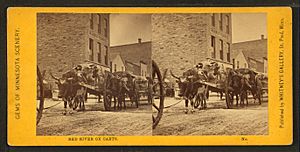

The summer hunts grew bigger over time. In 1820, there were 540 Red River carts. This grew to 689 carts in 1825, 820 in 1830, 970 in 1835, and 1,210 carts in 1840.

In 1840, a large group left Fort Garry on June 15. It included 1,210 Red River carts, 620 hunters, 650 women, 360 boys and girls, 403 buffalo runner horses, 655 cart horses, 586 oxen, and 542 dogs. In three days, they reached their meeting point at Pembina, North Dakota, about 60 miles (97 km) south, and set up a tent city.

The carts were arranged in a strong defensive circle with their forks pointing outwards. Inside the circle, tents were set up in rows on one side, and the animals were kept on the other side when it was safe.

At Pembina, they counted everyone taking part (1,630 people in 1840). A general meeting was held, and leaders were chosen. In 1840, ten captains were picked, with Jean Baptiste Wilkie chosen as the war chief and president of the camp. Each captain had ten soldiers under them. Ten guides were also chosen. A smaller group of leaders also met to set the rules or laws for the hunt.

Leaving Pembina on June 21, the group traveled 150 miles (240 km) southwest, reaching the Sheyenne River nine days later. On July 3, they saw buffalo 100 miles (160 km) further. About 400 mounted hunters killed around 1,000 buffalo. Women then arrived in carts to cut up the meat and bring it back to camp. It took the women several days to prepare the dried meat. The camp then moved to another spot. That year, the hunting group returned to Fort Garry with about 900 pounds (410 kg) of buffalo meat per cart, or 1,089,000 pounds (494,000 kg) in total. This came from between 10,000 and 10,500 buffalo.

Autumn Hunts

The autumn hunt started in September and finished in late October or early November. When the hunters returned, about half of the pemmican and dried meat was kept for their winter food. The rest was sold to the Hudson's Bay Company at Fort Garry. Hunters also had some fresh meat, which was kept cold by the weather. This hunt was smaller than the summer hunt. Many hunters, called hivernants or winterers, who had been on the summer hunt, would leave the settlements to spend the winter on the Canadian Prairies with their families to trap and hunt. Early fall was also harvest season, so more family members were needed to stay home and farm.

Some products from these hunts, especially good buffalo robes taken from November to February, were also traded along the Red River Trails to the American Fur Company at Fort Snelling. They were exchanged for goods like sugar, tea, and ammunition.

Conflicts with the Sioux

During the 1840s and 1850s, the Métis followed the buffalo herds further into the Dakota Territory. This led to conflicts with the Sioux people. Cuthbert Grant, an early captain of the buffalo hunt, made a treaty in 1844. Other treaties were made in 1851 and 1854, but Métis hunting groups were still attacked by the Sioux. Jean Baptiste Wilkie, who led the 1840, 1848, and 1853 summer hunts, helped make a peace treaty in 1859 and another in 1861. These treaties were between the Métis, Chippewa, and Sioux (Dakota) to set hunting boundary lines. However, these peace efforts did not last, and conflicts continued even after the Dakota War of 1862.

In the 1848 summer hunt, a group of 800 Métis led by Jean Baptiste Wilkie and 200 Chippewa led by Chief Old Red Bear, with over 1,000 carts, met the Sioux in the Battle of O'Brien's Coulée near Olga, North Dakota.

Between July 13 and 14, 1851, a large group of Sioux attacked the St. François Xavier hunting camp in North Dakota. This resulted in the last major battle, the Battle of Grand Coteau (North Dakota), fought between the two groups. The Métis won this battle.

At the Battle of Grand Coteau, 17-year-old Isadore Dumont and 13-year-old Gabriel Dumont fought alongside their father. Gabriel Dumont later became a famous Métis leader.

How the Hunts Were Governed

To make sure the hunts were successful, they had a clear leadership structure. This included a chief, a council, scouts, soldiers, and lookouts. The chief and council were elected by the families from the three Métis hunting groups.

At the meeting point in Pembina, they would count everyone taking part (1,630 people in 1840). Then, the heads of the main Métis families would vote to choose the main hunt chief and 10 to 12 councillors, or hunt captains. Each captain had ten soldiers under them. Ten guides were also chosen. A smaller council of leaders also met to set the rules or laws of the hunt.

This leadership was not overly strict. If a decision was beyond their usual power, they had to ask the heads of all families. The Métis believed in personal freedom but also in working together as a community and family. This leadership style allowed for both independence and group organization.

Laws of the Buffalo Hunt

In 1840, specific rules were put in place for the hunt. These rules made sure no hunter acted selfishly or harmed other members of the group.

- No buffalo to be run on the Sabbath-Day.

- No party to fork off, lag behind, or go before, without permission.

- No person or party to run buffalo before the general order.

- Every captain with his men, in turn, to patrol the camp, and keep guard.

- For the first trespass against these laws, the offender to have his saddle and bridle cut up.

- For the second offence, the coat to be taken off the offender's back, and be cut up.

- For the third offence, the offender to be flogged.

- Any person convicted of theft, even to the value of a sinew, to be brought to the middle of the camp, and the crier to call out his or her name three times, adding the word "Thief", at each time.

These rules and leadership style became a way for Métis communities to govern themselves. For example, in 1873, the Southbranch settlements organized their own local government under Gabriel Dumont, based on these very laws of the buffalo hunt.

Fair Practices During the Hunt

The Laws of the Buffalo Hunt created a structured and fair way to hunt. These laws focused on behaviors that could hurt the hunt for everyone. For instance, people hunting bison ahead of the main group could scare the herds away, making it harder for everyone.

These laws also showed the strong community spirit and fair values of Métis society. This included sharing the animals killed so that every family received enough meat, no matter how many animals one person killed. Also, the hunt chief would make at least one special pass through the herd. Any animal he killed was given to the old and sick who couldn't hunt for themselves. These practices made sure everyone had a reason for the hunt to succeed, by making things fair among families and recognizing both family independence and working together.

Pemmican Trade

The Métis would turn buffalo meat into bags of pemmican and bring them north to trade at the North West Company posts. After the North West Company joined with the Hudson's Bay Company, most of the pemmican was sold to the Hudson's Bay Company at Red River.

The pemmican, which forms the staple article of produce from the summer hunt, is a species of food peculiar to Rupert's Land. It is composed of buffalo meat, dried and pounded fine, and mixed with an amount of tallow or buffalo fat equal to itself in bulk. The tallow having been boiled, is poured hot from the caldron into an oblong bag, manufactured from the buffalo hide, into which the pounded meat has previously been placed. The contents are then stirred together until they have been thoroughly well mixed. When full, the bag is sewed up and laid in store. Each bag when full weighs one hundred pounds. It is calculated that, on an average, the carcass of each buffalo will yield enough pemmican to fill one bag.

—Red river by Joseph James Hargrave

The smaller buffalo cow was the main target for hunting. A buffalo cow, weighing about 900 pounds (410 kg), would give about 272 pounds (123 kg) of meat, or 54 to 68 pounds (25 to 31 kg) of dried meat. It takes about 4 to 5 pounds (1.8 to 2.3 kg) of fresh meat to make 1 pound (0.45 kg) of dried meat. A bag of pemmican, called a taureau, weighed between 90 to 100 pounds (41 to 45 kg) and contained 45 to 50 pounds (20 to 23 kg) of dried, pounded meat.

The Hudson's Bay Company relied on products from the buffalo hunts well into the 1870s. For the Métis living near the prairie, the pemmican trade was as important for getting trade goods as the beaver trade was for First Nations further north. This trade was a big reason why a unique Métis society developed. Bags of pemmican were sent north and stored at major fur trading posts like Fort Garry and Norway House. Pemmican was so important that in 1814, Governor Miles Macdonell almost started a war (Pemmican War) with the Métis when he tried to stop the export of pemmican from the Red River Colony.

Buffalo Robe Trade

Winter hunts from Red River began in the early 1800s. Most people spent winters in Pembina hunting buffalo.

In 1823, Pembina was found to be just south of the Canada–United States border. In 1844, Norman Kittson opened a successful trading post at Pembina, competing with the Hudson's Bay Company.

By 1849, the Hudson's Bay Company had lost its fur trade monopoly. This meant the Métis could now sell their furs freely. As the price of buffalo robes went up, so did the number of carts heading south from Pembina to Saint Paul, Minnesota each year. This increased from 6 carts in 1844 to 400 carts in 1855, 600 to 800 carts in 1858, and 2,500 carts in 1869. Most of this freight was buffalo robes (25,000 in 1865 alone).

A buffalo robe is a buffalo hide that has been treated, with the hair left on. Only hides taken during the winter hunts, between November and March, were good for buffalo robes because their fur was at its best then. Summer hides and bull hides had little value for traders.

Winter Settlements (Hivernants)

To take advantage of the demand for buffalo robes, many more Métis would spend the winter on the prairie. From the 1840s to the 1870s, Métis hivernants (winterers) set up hunting camps in places like Turtle Mountain Provincial Park, Wood Mountain, Saskatchewan, and in Montana.

New permanent settlements were also started. They were similar to the Red River settlements, built on river lots. These new settlements also organized their own summer, autumn, and winter hunts. St. Albert, Alberta, started in 1861, became a main gathering spot for French Métis buffalo hunters from the Fort Edmonton area.

The St. Albert fall hunt of 1872 saw most hunters caught in an October blizzard on the prairies. They found shelter at Buffalo Lake (Lac du boeuf), where they spent the winter. Buffalo Lake (Alberta) and the nearby Red Deer River valley became a winter settlement with over 80 cabins. The last hunts in 1877 and 1878 were not successful, and Buffalo Lake, perhaps the largest of these winter settlements, was abandoned.

Buffalo Herds

There were two large buffalo herds hunted by the Red River hunters: those of the Grand Missouri Coteau and the Red River of the North, and those of the Saskatchewan River. Other large herds lived south of the Missouri River.

The great western herds winter between the south and the north branches of the Saskatchewan, south of the Touchwood Hills, and beyond the north Saskatchewan in the valley of the Athabasca; They cross the South Branch in June or July, visit the prairies on the south side of the Touchwood Hill range, and cross the Qu'appelle valley anywhere between the Elbow of the South Branch and a few miles west of Fort Ellice on the Assiniboine. They then strike for the Grand Coteau de Missouri, and their eastern flank often approaches the Red River herds coming north from the Grand Coteau. They then proceed across the Missouri up the Yellow Stone, and return to the Saskatchewan and Athabaska as winter approaches, by the flanks of the Rocky Mountains.

—Henry Youle Hind 1860

The Missouri Coteau, or Missouri Plateau, is a high, flat area that stretches along the eastern side of the Missouri River valley in central North Dakota and north-central South Dakota in the United States. It also extends into Saskatchewan and Alberta in Canada.

Images for kids

-

Homes on narrow river lots along the Red River near St. Boniface in July, 1822 by Peter Rindisbacher

-

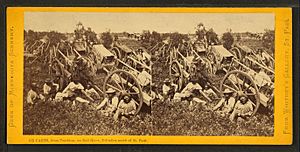

Paul Kane witnessed and participated in the annual Métis buffalo hunt in June 1846 on the prairies in Dakota.

-

Map of the extermination of the bison to 1889. This map based on William Temple Hornaday's late-19th century research. Original range Range as of 1870 Range as of 1889