Gabriel Dumont (Métis leader) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

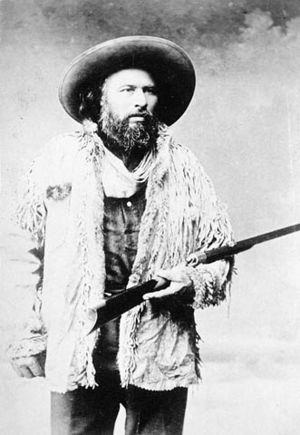

Gabriel Dumont

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | December 1837 modern-day Winnipeg

|

| Died | 19 May 1906 (aged 68) St. Isidore-de-Bellevue, Saskatchewan, Canada

|

| Nationality | Métis |

| Known for | Métis military leader |

| Spouse(s) | Madeleine Wilkie |

Gabriel Dumont (1837–1906) was a brave and important leader of the Métis people in Canada. He is famous for his role in the North-West Resistance. This included big battles like Batoche, Fish Creek, and Duck Lake. Dumont also helped sign peace agreements with the Blackfoot tribe, who were often enemies of the Métis.

Dumont was born in 1837 in the Red River Valley. He didn't go to school much but could speak seven different languages! When he was young, his family hunted buffalo for food and traded with the Hudson's Bay Company. After leading the Métis with Louis Riel, Dumont traveled in the United States. He gave speeches and helped with political campaigns. In 1889, he shared his life story in Quebec.

Dumont was a respected leader in the Métis community. He was known for his political and military skills. In 1882, he helped end a treaty between the Métis and the Dakota. A year later, he was chosen as the main hunt chief for the Saskatchewan Métis. Dumont was like the top general for the Métis people. He played a huge part in their fight against the Canadian government during the North-West Resistance. He was a key figure in the Battle of Duck Lake, and the battles of Fish Creek and Batoche.

Today, Dumont's grave is in Batoche. His legacy lives on through the Métis people. The Gabriel Bridge over the Saskatchewan River is named after him. Many schools and research places also carry his name. Books and poems have been written about his life and his importance as a leader.

Contents

Growing Up Métis

Gabriel Dumont was born in December 1837. He was the fourth child and oldest son in a family of 11 children. His birthplace is now part of Winnipeg.

His parents were Isidore Dumont and Louise Laframboise. They lived in the Red River Colony. Gabriel's grandfather was a French-Canadian voyageur (a fur trader and explorer). His grandmother was a First-Nations woman. Because of his family's background, Gabriel didn't get much formal schooling. This was common for many people at that time. He spent most of his childhood traveling across the Canadian Prairies. He followed the bison herds and learned how to be a skilled hunter.

The Dumont family was well-known in Red River for their buffalo hunting. They also had a long history of leading hunting groups in Saskatchewan. They earned money by hunting in lands controlled by the Hudson's Bay Company. Their main income came from trading pemmican (a dried meat and fat mixture) with the company. Gabriel learned buffalo hunting as a child. He became an expert at prairie life. These skills would help him greatly in the future.

In 1858, Dumont married Madeleine Wilkie. She was the daughter of Jean Baptiste Wilkie. As a hunter, Dumont traded with different tribes. He learned many languages, which made him even more valuable to his people. In 1868, Dumont and his wife settled permanently in the Batoche area.

Dumont was very talented. He was a great hunter and could speak many languages. People said he could talk to others in at least seven different languages. However, he only knew a few English phrases. He was also an excellent marksman with both a bow and a rifle. Plus, he was a very good horseman. Like other Métis leaders such as Louis Riel, Dumont was skilled at diplomacy on the northern plains.

Leading the Resistance

Dumont first experienced plains warfare at age 13 in 1851. He fought in the Battle of Grand Coteau. Here, he helped defend a large Métis camp against a much bigger group of Yankton Sioux warriors.

In 1862, when he was 24, Dumont acted as a go-between for the Métis and the Dakota people. He was with his father. Later, Dumont helped sign a peace agreement with the Blackfoot. This brought a long period of peace with the Métis' traditional enemies.

Even though he was a Métis leader, Dumont wasn't part of the Red River Rebellion (1869-1870). But he quickly went to Fort Garry to offer military help. This was when Colonel Garnet Wolseley's troops moved into the area.

Around 1885, the North-West Resistance began. Dumont's army of 300 Métis soldiers gathered near Duck Lake on March 26. A fight broke out that day between the Métis and the North-West Mounted Police. Dumont's brother, Isidore, was killed during a failed peace talk. Dumont himself was grazed by a bullet on his head. This cut an artery. He had to recover from his injury while the rest of the Resistance continued. But this injury didn't stop him from leading his soldiers.

Dumont also helped find people who were not loyal among the Saskatchewan Métis. He was part of the arrest of Alexander Monkman. Dumont protected Louis Riel by jumping in front of Monkman's gun when he pulled it on Riel. This led to Monkman's quick arrest. Dumont knew that more Canadian troops, led by General Frederick Middleton, were coming. To fight this threat, Dumont suggested attacking railroads and fighting Canadian soldiers for a long time. Riel wanted a peaceful solution, and Dumont followed Riel's decisions.

Dumont's 300 Métis soldiers fought the Canadian soldiers on April 24 at Fish Creek. The Métis' efforts made General Middleton stop his advance toward Batoche. The battle lasted only one day. The Métis soldiers were outnumbered five to one. But Dumont's clever leadership allowed them to push back the attackers. This let the Métis soldiers retreat safely to Batoche. When the Canadian soldiers reached Batoche, Dumont led a four-day defense of the Métis community. Even though the Métis were greatly outnumbered, there was no clear winner after the first day. Dumont's group damaged a military steamer and stopped several of Middleton's attacks. The Métis used a smart tactic: they dug holes about 75 meters apart. This allowed their troops to hide and move across the land. They could watch the Canadians and attack easily. By the fourth day, the Métis soldiers ran out of ammunition. They were shooting nails and metal pieces. That day, the Canadian soldiers broke through Dumont's lines and took Batoche. Many Métis were saved because of the holes they had dug. For days afterward, Dumont stayed near Batoche. He made sure that blankets were given to the Métis women and children who had lost their homes. During this time, Dumont also looked for Riel. Riel had surrendered to the Canadian soldiers on May 15. When Dumont learned about Riel's capture, he quickly left Batoche and went to the United States.

After crossing into the United States near the Cypress Hills and Montana Territory, Dumont and his friend Michel Dumas were quickly stopped. However, they were soon released after an order came from the Oval Office. Even though Dumont was hiding, he was still wanted in Canada. He became a kind of folk hero in Saskatchewan. People said that the soldiers looking for him didn't try very hard to find him. They heard that "le petit," his famous rifle, was still with him.

In July 1886, the Canadian government announced that Dumont could return safely without punishment. He eventually came back to Batoche. There, he wrote down two separate accounts of the North-West Resistance.

Political Vision

Dumont's skills as a buffalo hunter quickly made him important in politics. By 1863, there were about 200 buffalo hunters among the Saskatchewan Métis. This was enough people to need some kind of organization. In 1863, he was first elected as the hunt chief of the Saskatchewan Métis. He stayed in this position until 1881. This was around the time that the buffalo herds almost completely disappeared from his area. Dumont's experience with buffalo hunting gave him a good understanding of how the buffalo trade was declining in the 1870s.

He was known as a leader with a clear plan for the Métis. He knew that fewer buffalo and more Canadian farming from the east would bring big changes to the prairies. His political goal was to keep the Saskatchewan Métis independent, both politically and economically. In December 1873, Dumont called a meeting to form a government for the Métis at St. Laurent. He was immediately elected leader of the St. Laurent council. As leader, Dumont created a constitution for the Métis that they followed for some time.

As president of the council, Dumont oversaw a group of elected Métis councillors. He also helped manage relations between the council and the people of St. Laurent. During this time, the Canadian government started to claim power in the region. This caused conflict with Dumont and his council. At first, Dumont was calm. He told the government that the local government's purpose was simply to govern locally. Dumont said the council's goal was not to start a rebellion. Because of Dumont's words, government officials didn't worry much.

However, Dumont did want a certain level of full authority. When Canadian government land surveyors arrived in Saskatchewan in the 1870s, they ignored the Métis system of land tenure (how land was owned and used). When the North-West Mounted Police arrived in 1874, it showed how tense the situation was. Sir John A. Macdonald's government had no plans to treat the Métis as a self-governing group.

Dumont was re-elected president and leader of the St. Laurent council in December 1874. To keep order, Dumont's government tried to fine Métis who ignored the rules of the buffalo hunt. These people didn't like Dumont's tactics. They complained to the Hudson's Bay Company agent, Lawrence Clarke. Clarke sent their concerns to Lieutenant Governor Alexander Morris. He claimed the Métis were openly rebelling against the Canadian government. After this, the North-West Mounted Police were sent to investigate. They found no problem with Dumont's actions. However, this incident basically ended the rule of the St. Laurent governing council, though the council itself remained.

In the 1880s, Dumont's council sent requests to Ottawa. They asked the government to recognize the Métis' traditional land holdings. When the prime minister and his cabinet didn't answer these requests, Dumont and the Métis felt they had to protect their land more directly. In March 1884, Dumont called a meeting. He asked Louis Riel to take over the leadership role he had been holding. So, Dumont and three close friends traveled to St. Peter's Jesuit Mission in Montana. They convinced Riel to come north to Saskatchewan. From then on, Dumont and Riel stayed close friends.

In March 1885, Dumont called a big meeting of the St. Laurent Métis at Batoche. During the meeting, some Indigenous people suggested a more forceful approach. They wanted to defend their lands against the Canadian government using weapons. By the end of the meeting, a new temporary government was formed. It was led by Dumont and called the Provisional Government of Saskatchewan. This new government directly challenged Ottawa's rule. Dumont was chosen to be the adjutant governor of this new government. Riel was officially the main leader and could overrule Dumont. But Dumont was still in charge of many Métis political and military decisions until he stopped actively governing.

His Last Years and Legacy

In the 1870s and 1880s, Dumont owned a farm near the South Saskatchewan River. He worked the farm and ran a ferry service called "Gabriel's Crossing." It was about 10 km upstream from another ferry. Dumont and his wife Madeleine were among many Métis families pushed out of Manitoba by the Canadian government.

In June 1886, Dumont briefly worked in Buffalo Bill's Wild Wild West Show. He was presented as a brave and excellent shot. Later that summer, he traveled to the northeastern States. He gave speeches and helped with political campaigns. Dumont soon grew tired of politics. He returned to the Wild Wild West Show. In 1903, he settled down at a relative's property. He went back to hunting, fishing, and trapping. He died at age sixty-eight on May 19, 1906, in Batoche. He passed away from heart failure.

Gabriel Dumont's legacy as a Métis leader is second only to Louis Riel's. His impact is remembered through schools, museums, institutions, books, and important places. In 2008, a provincial minister said that the 125th anniversary of the 1885 Northwest Resistance in 2010 was a great chance to tell the story of the Métis and First Nations peoples' struggle. This struggle shaped Canada today. Batoche, where the Métis Provisional Government was, is now a National Historic Site.

The Gabriel Dumont Institute of Native Studies and Applied Research in Saskatchewan was named in his honor in 1980. In 1985, a scholarship fund was created with $1.24 million. In 1993, the institute and the University of Saskatchewan created the Gabriel Dumont College. The Gabriel Bridge was built in 1969 over the South Saskatchewan River. It is at the site of Gabriel's Crossing, where he ran a small store, a billiards hall, and a ferry service. In 1998, a public French-first-language high school in London, Ontario, was renamed École secondaire Gabriel-Dumont in his honor.

See also

- Indigenous Canadian personalities

- List of Métis people

- Southbranch Settlement

- James Isbister

| Madam C. J. Walker |

| Janet Emerson Bashen |

| Annie Turnbo Malone |

| Maggie L. Walker |