North-West Resistance facts for kids

The North-West Resistance was a short but important conflict in Canada in 1885. It involved the Métis and some First Nations groups, mainly the Cree and Assiniboine. They were fighting against the Canadian government in what is now Saskatchewan and Alberta.

The Métis were led by Louis Riel, who had returned from the United States. With help from Gabriel Dumont, Riel formed a temporary government on March 18, 1885. This led to fighting that lasted until early June.

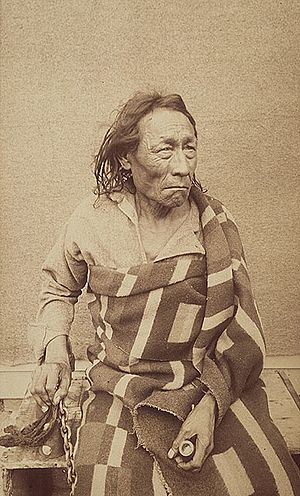

About 250 Métis and 250 First Nations men, including leaders like Big Bear and Poundmaker, fought in the resistance. The Canadian government sent about 5,500 soldiers, including the North-West Mounted Police, to stop them.

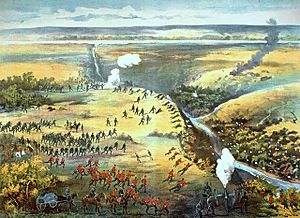

The Métis captured some small settlements and won a few battles, like at Duck Lake and Fish Creek. However, the government forces were much larger and had more supplies. The conflict ended when government troops won the Battle of Batoche.

After the fighting, many First Nations leaders surrendered. Some were put on trial and sent to prison. Louis Riel was also captured, tried, and found guilty of treason. He was executed, which caused a lot of debate across Canada.

Quick facts for kids North-West ResistanceRébellion du Nord-Ouest (French) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Top: Battle of Batoche Bottom: Battle of Cut Knife |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

|

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

|

||||||

Contents

Understanding the Conflict's Names

This conflict has several names, like the North-West Resistance or the North-West Rebellion. These different names show how people view the events. Some call it a "rebellion" because it was an uprising against the government. Others call it a "resistance" to show that Indigenous peoples were defending their lands and way of life.

Why the Conflict Started

The North-West Resistance happened because many Métis and First Nations people were unhappy. They felt the Canadian government was not listening to their concerns.

Land and Way of Life Changes

After an earlier conflict called the Red River Uprising, many Métis moved to what is now Saskatchewan. They settled along rivers and farmed their land in long, narrow strips. This was their traditional way of life.

However, in 1882, government surveyors started dividing the land into square sections. This new system did not respect the Métis' existing farms. Some Métis families even found that their homes and villages had been sold to other companies.

The Métis also relied on bison (buffalo) hunting for food and trade. But by the 1880s, the buffalo herds were almost gone. This made it very hard for them to survive.

Unfair Treaties and Hardship

First Nations people were also facing difficult times. The government had signed treaties with them, but sometimes did not keep its promises. Food and supplies were often held back, causing great hardship and hunger.

Cree chief Big Bear tried to talk with the government to improve the treaties. He wanted a better future for his people.

In 1884, the Métis asked Louis Riel to return from the United States. They wanted him to speak for them to the government. Riel presented a list of demands, asking for Métis land rights and a special office to handle land issues.

When the government's response was unclear, Riel and other Métis leaders formed a temporary government on March 18, 1885. They hoped this would make the federal government listen, just like it had in 1869.

However, things were different this time. The Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) was mostly built across the prairies. This meant the government could move soldiers much faster than before. The North-West Mounted Police (NWMP) also had a stronger presence in the area.

Some Cree groups, facing starvation, took action around the same time as the Métis uprising. These actions, like the incident at Frog Lake, were mainly due to their desperate situation and hunger.

Who Lived in the Area

In 1885, about 48,000 people lived in the areas of Assiniboia, Saskatchewan, and Alberta. About 40% of these people were Status Indians.

The District of Saskatchewan had about 10,500 people. The Southbranch settlements, where Louis Riel's temporary government was based, had about 1,300 people. The Battleford area, where the Cree uprising happened, had about 3,600 people.

Most of the 5,400 Métis in Saskatchewan tried to stay neutral. About 350 armed Métis supported Riel. These supporters were often older Métis who had strong ties to First Nations communities.

The Conflict Unfolds

On March 18, 1885, Louis Riel, Gabriel Dumont, and others formed the Provisional Government of Saskatchewan. Riel wanted to lead a movement to get the government's attention.

Early Battles and Government Response

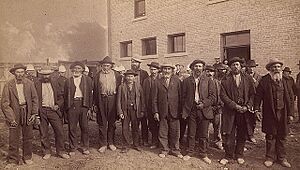

News of the temporary government reached Ottawa. On March 23, Prime Minister John A. Macdonald confirmed the uprising was happening. The government quickly sent Major General Frederick Middleton and Canadian militia troops to the West.

On March 26, a force of police and volunteers, led by Superintendent Leif Crozier, went to confront the Métis fighters led by Gabriel Dumont near Duck Lake. The Battle of Duck Lake that followed ended in a decisive victory for the Métis. Five Métis fighters were killed, including Gabriel Dumont’s brother. Dumont himself was also hurt during the battle.

On March 30, a group of Cree, who were very short on food, approached Battleford. The people living there fled to a nearby police post. The Cree then took food and supplies from the empty stores and houses.

Important Events and Victories

The Canadian government quickly gathered soldiers from across the country. Many of these soldiers were inexperienced. They faced harsh winter weather and difficult travel conditions on their way west.

On April 2, at Frog Lake, a group of Cree led by Wandering Spirit attacked local officials. They were angry about unfair treaties and the lack of food. They killed several officials and took hostages. Wandering Spirit and others were later executed for these actions.

Major General Middleton led his troops from Qu'Appelle towards Batoche. On April 24, his column fought the Battle of Fish Creek against 200 Métis fighters. The Métis won this battle, which slowed Middleton's advance.

Another government force, led by Lieutenant Colonel William Dillon Otter, went to Battleford. On May 2, they attacked a Cree camp at Cut Knife Hill. Cree fighters, led by Fine-Day, successfully defended their camp. Otter's troops were forced to retreat.

The End of the Conflict

Métis Resistance Ends

On May 12, Middleton's forces captured Batoche. The Métis fighters were greatly outnumbered and ran out of ammunition after three days of fighting. They were eventually overcome by the Canadian soldiers.

Louis Riel surrendered on May 15. Gabriel Dumont and other rebels escaped to the United States. The defeat at Batoche and Riel's capture ended the Métis uprising.

First Nations Surrender

After their defeat at Cut Knife Hill, Otter's troops secured Battleford. Poundmaker and other chiefs loyal to him surrendered on May 26.

Major General Thomas Bland Strange led another force, the Alberta Field Force, to deal with Big Bear's band. On May 28, they fought Big Bear's group at Frenchman's Butte. Big Bear's fighters won this battle and moved north.

The last armed fight of the resistance happened on June 3 at Loon Lake. Scouts led by Sam Steele caught up to Big Bear's group. Big Bear's fighters, almost out of ammunition, released their hostages and fled.

Most of Big Bear's fighters surrendered in the following weeks. Big Bear himself surrendered on July 2 near Fort Carlton.

What Happened After

The North-West Resistance was Canada's first major military action as a country. It cost about $5 million.

The Railway's Role

The Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) was very important in the government's response. It allowed troops to be moved quickly across the country. This speed helped the government overcome the resistance much faster than previous conflicts. The success of the railway in this conflict helped it get the money it needed to finish building the line.

Trials and Consequences

After the conflict, Louis Riel was put on trial for treason. He was found guilty and executed. This decision caused a lot of disagreement between English and French-speaking Canadians.

Poundmaker and Big Bear were also sentenced to prison.

Several other Indigenous men were put on trial and executed for actions that happened outside the main battles. These included Wandering Spirit and others involved in the Frog Lake incident.

Lasting Effects on Communities

The conflict had long-lasting effects. The French language and Catholic religion faced challenges in Saskatchewan and Manitoba. Many Métis were forced to live on less desirable land.

Riel's execution created lasting anger in Quebec. It made many French Canadians distrust English-speaking politicians.

The government did send food and supplies to help the Cree and Assiniboine who were facing shortages. New land grants were given to Métis in Saskatchewan to address their land claims. However, many Métis later sold their land to speculators.

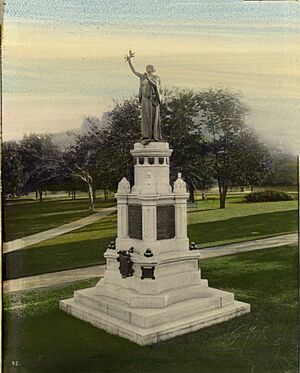

Those who served in the Canadian Militia and North-West Mounted Police during the conflict received the North West Canada Medal.

Remembering the Past

Many places today remember the North-West Resistance.

Historic Sites and Monuments

Batoche, where the Métis temporary government was formed, is now a National Historic Site. It includes Gabriel Dumont's grave, the church, and Métis rifle pits.

The Royal Canadian Mounted Police training center in Regina has a chapel built in 1885. It was used to hold prisoners. Louis Riel's trial also took place in Regina. He was executed there on November 16, 1885. His body was later buried in Manitoba. Highway 11 is named the Louis Riel Trail.

Fort Carlton Provincial Historic Site has been rebuilt. It was important for early negotiations and where Big Bear surrendered.

Duck Lake has a historical museum and interpretive center. A monument marks where the first shots of the Battle of Duck Lake were fired.

The Battle of Fish Creek National Historic Site preserves the battlefield where the Métis won an important victory.

The Marr Residence in Saskatoon served as a hospital for wounded soldiers.

Fort Battleford National Historic Site was a military base and a refuge for settlers. Poundmaker was arrested there, and several First Nations men were executed there.

Fort Pitt is a provincial park and national historic site. It was the scene of a battle and where a treaty was signed.

Frog Lake Massacre National Historic Site of Canada marks the location of the Cree uprising.

Frenchman Butte is a national historic site where a battle between Cree and Canadian troops took place.

At Cutknife, there is a monument to Poundmaker and Big Bear. A cairn on Cut Knife Hill overlooks the battle site.

Steele Narrows Provincial Historic Park at Loon Lake marks the site of the last battle of the conflict.

Monuments in places like Queen's Park in Toronto and Winnipeg remember the Canadian militiamen who served.

In Books and Movies

The North-West Resistance has been featured in many stories:

- Red Trails (1935) by Stewart Sterling features a Mountie during the resistance.

- North West Mounted Police (1940), a film by Cecil B. DeMille, shows a Texas Ranger helping the police.

- Buckskin Brigadier: The Story of the Alberta Field Force (1955) by Edward McCourt is a historical novel.

- The Magnificent Failure (1967) by Giles A. Lutz is another historical novel.

- Riel, a Canadian TV film, shows both the 1870 and 1885 uprisings.

- The Temptations of Big Bear (1973) by Rudy Wiebe tells the story of Chief Big Bear.

- Lord of the Plains (c. 1990) by Albert Silver focuses on Gabriel Dumont.

- Battle Cry at Batoche (1998) by B. J. Bayle tells the story from a Métis point of view.

- Song of Batoche (2017) by Maia Caron is a historical novel about the resistance.

See also

- Index of articles related to Aboriginal Canadians

- List of incidents of civil unrest in Canada

- Military history of Canada

| Misty Copeland |

| Raven Wilkinson |

| Debra Austin |

| Aesha Ash |