Battle of Cut Knife facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Cut Knife |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the North-West Rebellion | |||||||

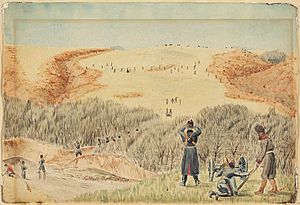

A drawing from the time, showing the Battle of Cut Knife. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Cree Assiniboine |

|||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Poundmaker Fine Day |

William Dillon Otter | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 50 to 250 | 350 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 5 dead 3 wounded |

8 dead |

||||||

| Official name: Battle of Cut Knife Hill National Historic Site of Canada | |||||||

| Designated: | 1923 | ||||||

The Battle of Cut Knife happened on May 2, 1885. It was a fight between Canadian forces and First Nations people. A group of Canadian soldiers, police, and volunteers attacked a camp of Cree and Assiniboine people. This camp was near Battleford, in Saskatchewan. The First Nations fighters successfully defended their camp. They forced the Canadian forces to leave. Both sides had people killed and wounded in the battle.

Contents

Why the Battle Happened

The North-West Rebellion Begins

In the spring of 1885, the Métis people in the District of Saskatchewan formed their own government. Their leader was Louis Riel. They took control of the area around Batoche. Riel was also talking with First Nations groups, like the Cree and Assiniboine. The Canadian government worried that this resistance would spread. They quickly prepared to send soldiers to stop it.

Poundmaker's Visit to Battleford

A group of Cree people, led by Poundmaker, went to Battleford. They wanted to ask the Indian agent, Mr. Rae, for more supplies. Many of Poundmaker's people were very hungry. They also wanted to talk about the political situation.

People in Battleford and nearby settlers heard that many Cree and Assiniboine were coming. They became scared for their safety. On March 30, 1885, many townspeople left their homes. They went to hide inside the North-West Mounted Police fort, Fort Battleford.

When Poundmaker and his group arrived, Mr. Rae refused to meet them. He kept them waiting for two days. Poundmaker's people were still hungry because Rae would not give them supplies.

Looting and Conflict

Around this time, empty homes and shops in Battleford were looted. It is not clear who did the looting. Some said Poundmaker's people were responsible. But others said white settlers had already done most of it. Oral stories from First Nations people say that Nakoda people did the looting. They also say Poundmaker tried his best to stop it. Poundmaker's group left Battleford the next day.

Meanwhile, some Assiniboine people south of Battleford heard about the Métis rebellion. A small group of them had a conflict with a local farmer and an Indian agent. Then, they went north to Battleford to meet Poundmaker. More homes and businesses in Battleford were looted and burned. There is still debate about who caused this damage.

Otter's March to Battleford

The Canadian government sent Major General Frederick Dobson Middleton to stop the Métis rebellion. The small police force at Fort Battleford was protecting nearly 500 civilians. They asked for more soldiers. They also quickly formed a local guard to protect the fort.

General Middleton sent a group of soldiers led by Lieutenant Colonel William Otter to help Battleford. Otter's group had about 763 men. These included soldiers from different Canadian army units and police. They traveled by train to Swift Current. Then, they marched to Battleford, arriving on April 24.

When Otter arrived, he found hundreds of people crowded into the fort. Poundmaker's followers were not there. The townspeople and settlers were very happy Otter had arrived. They wanted revenge on the First Nations people for their losses. Many of Otter's soldiers were new and wanted to fight.

Otter Decides to Attack

The townspeople and his own soldiers pressured Otter to act. General Middleton had ordered Otter to stay in Battleford. But Otter asked the Lieutenant-Governor of the Northwest Territories, Edgar Dewdney, for permission. He wanted to "punish Poundmaker." Permission was given.

Otter left some soldiers in Battleford. He then led a group of 392 men to attack the Cree and Assiniboine. This group included 75 North-West Mounted Police on horses. It also had Canadian army soldiers and volunteers. Otter brought two cannons and a Gatling gun (an early machine gun).

He left on the afternoon of May 1. His plan was to march until dark, rest, and then continue. He wanted to attack the Cree and Assiniboine camp early in the morning while they were sleeping.

Meanwhile, the Cree were camped on their land west of Battleford. This was on Cut Knife Creek. Other groups, including Assiniboine, joined them. They knew many Canadian soldiers were in the area. They decided to protect themselves.

According to Cree custom, the war chief Fine Day became the leader. He took over from Poundmaker (the 'political chief') until the fighting was over. The entire camp moved to the west side of Cut Knife Creek. Behind the camp was Cut Knife Hill. On both sides of the hill were deep ravines with bushes and trees. There were nine Cree groups and three Assiniboine groups. About 1500 men, women, and children were in the camp.

The Battle of Cut Knife

Surprise Attack and Counterattack

Just after sunrise on May 2, Otter's soldiers arrived. Otter had expected the camp to be on the flat land east of the creek. He did not expect to cross the creek. After his soldiers crossed the creek, they had to walk through a marsh. Then, they reached the camp.

An old Cree man named Jacob with Long Hair heard the soldiers crossing the creek. He woke up the camp. Colonel Otter set up his two cannons and Gatling gun. He started firing at the camp. At first, there was total confusion. The gunfire hit tipis and destroyed parts of the camp. Women and children ran to the safety of the ravines.

A group of Assiniboine warriors bravely charged Otter's men. They wanted to stop them from harming the women and children. Other warriors moved into the ravines. Fine Day went to the top of Cut Knife Hill. From there, he directed the Cree counterattack.

Fighting in the Ravines

The warriors fought in small groups. One group would run forward, attack the soldiers, and then quickly go back to the ravine. This made it hard for the soldiers to hit them. If the soldiers tried to attack warriors on one side, another group would rush out of the second ravine. They would attack the soldiers from behind. Other warriors protected the women and children.

Otter's soldiers could not attack well. They did not know where the enemy was or how many there were. An eyewitness, Robert Jefferson, said that only about 50 First Nations people fought. This was because few of them had weapons. However, other research suggests about 243 Cree and Assiniboine men were present. Some young boys also joined the fight.

Otter arranged his men in a wedge shape. Two lines of soldiers and police faced the two ravines. The volunteers and local soldiers guarded the back, facing the marsh.

Otter's Retreat

As the battle continued, Fine Day used a clever plan. His warriors moved along the two ravines. They got closer and closer to the soldiers. The warriors stayed hidden behind trees and bushes while they fired. Otter's men could not see anyone to shoot at.

Colonel Otter's soldiers were almost surrounded. The ravines were on their left and right. The marsh made it hard to escape from behind.

After six hours of fighting, Otter decided to leave. As his soldiers crossed the marsh, some of Poundmaker's fighters wanted to keep attacking. But Poundmaker asked them to let Otter's men go. They respected Poundmaker and allowed Otter to retreat to Battleford without further attack. Some historians believe Poundmaker's actions saved many of Otter's soldiers from being killed.

People Who Died

Some of the government soldiers who died were:

- John Rogers and William B. Osgoode, from the Guards Company of Sharpshooters (Ottawa)

- Corporal W. H. T. Lowry, from the North-West Mounted Police

What Happened After the Battle

The Battle of Cut Knife was the most successful battle for the First Nations during the North-West Rebellion. They knew the land well, which helped them. However, they were outnumbered, attacked by surprise, and did not have much ammunition.

Eight of Otter's soldiers were killed, and fourteen were wounded. Five First Nations people were killed, and three were wounded. One of those killed was a Nez Perce person who had come from the United States years before.

The battle made some of Otter's soldiers respect their enemy. Otter had expected Poundmaker's people to be surprised and give up quickly. But that did not happen.

Even though the Canadian forces lost this battle, they had more soldiers and better supplies overall. A few weeks later, the hungry Cree people went to Battleford to make peace with Major-General Middleton. Fine Day, the Cree war chief, escaped to the United States. Poundmaker was arrested and put in jail for seven months.

Lieutenant-Colonel William Otter survived the battle. He remained an important military leader. He commanded The Royal Canadian Regiment in the Boer War. He also oversaw Internment Camps during World War I.

Comparing to Little Bighorn

Many people compare this battle to the Battle of the Little Bighorn in the United States. There are some important similarities:

- In both battles, an army officer disobeyed orders.

- Both officers tried to surprise a Native camp.

- Both Custer and Otter misjudged the land. This slowed down their attacks.

- Both ended up surrounded by warriors and did not know where to charge.

However, there were big differences in the results. Otter knew when to retreat, and he was allowed to leave. Custer kept fighting, and hundreds of his soldiers died. Otter and most of his soldiers survived. They gained new respect for the First Nations warriors.

Legacy

"Cut Knife Battlefield. Named after Chief Cut Knife of the Sarcee in an historic battle with the Cree. On May 2, 1885, Lt. Col. W.D. Otter led 325 troops composed of North-West Mounted Police, "B" Battery, "C" Company, Foot Guards, Queen's Own and Battleford Rifles, against the Cree and Assiniboine under Poundmaker and Fine Day. After an engagement of six hours, the troops retreated to Battleford."

The place where the battle happened was named a National Historic Site of Canada in 1923.

There is a bronze statue at Cartier Square Drill Hall in Ottawa, Ontario. It honors William B. Osgoode and John Rogers. They were soldiers who died during the Battle of Cut Knife Hill.

In 2008, a government minister announced a special event. In 2010, there would be a 125th anniversary event for the 1885 Northwest Resistance. This was to tell the story of the Métis and First Nations peoples' struggle. It showed how it helped shape Canada today.

In the town of Cut Knife, you can find the world's largest tomahawk. There is also the Poundmaker Historical Centre and a monument to Big Bear. A stone monument (cairn) has been placed correctly on Cut Knife Hill. It overlooks the Poundmaker Battle site and the Battle River valley.

In May 2019, the government announced something important. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau would officially clear the name of Chief Poundmaker. He had been wrongly convicted of treason-felony. A formal apology was made on May 23, 2019.

Images for kids

| DeHart Hubbard |

| Wilma Rudolph |

| Jesse Owens |

| Jackie Joyner-Kersee |

| Major Taylor |