Military history of Canada facts for kids

The Military History of Canada

The military history of Canada includes hundreds of years of armed actions. These events happened both within the land that is now Canada and through actions by the Canadian military around the world. For thousands of years, Aboriginal peoples had conflicts between their tribes.

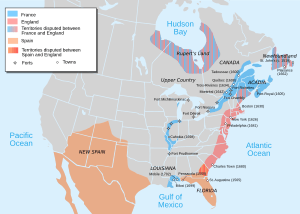

In the 17th and 18th centuries, Canada was a battleground for several colonial wars. These wars involved New France and New England, often with different First Nation groups as allies. After the Seven Years' War in 1763, Britain won. The French people living there became "British Subjects."

In 1774, the Quebec Act gave Canadians their first set of rights under British rule. The northern colonies decided not to join the American Revolution. They stayed loyal to the British Crown. Americans invaded in 1775 and 1812, but Canadian forces pushed them back. This threat helped lead to Canadian Confederation in 1867.

After Confederation, Canada created its own military. Canadian forces fought alongside British troops in the Second Boer War and First World War. Canada gained independence with the Statute of Westminster in 1931. Still, Canada supported Britain in the Second World War. Since then, Canada has joined large international groups for conflicts like the Korean War, the Gulf War, the Kosovo War, and the Afghan war. Canada is also known for its peacekeeping efforts worldwide.

Contents

- The Military History of Canada

- Indigenous Warfare and European Arrival

- 17th Century European Settlements

- 18th Century Conflicts

- Queen Anne's War and British Conquests

- Father Rale's War and Indigenous Rights

- King George's War: Louisbourg and Halifax

- Father Le Loutre’s War: British Expansion

- French and Indian War: The Fall of New France

- American Revolutionary War: Invasions and Raids

- French Revolutionary Wars: Newfoundland Expedition

- 19th Century Conflicts

- 20th Century Conflicts

- 21st Century Operations

- Canadian Crown and the Forces

- Peacekeeping: Canada's Global Role

- See also

Indigenous Warfare and European Arrival

Before Europeans arrived, Indigenous groups fought over land, resources, and honor. These battles were often formal and had few deaths. However, there is also evidence of more violent wars. Some First Nations groups were completely displaced by others. For example, the Dorset people of Newfoundland were replaced by the Beothuk.

Warfare was common among indigenous peoples of the Subarctic. But Inuit groups in the far North usually avoided direct war. They used traditional laws to solve problems instead.

People captured in fights were not always killed. Tribes sometimes adopted captives to replace lost warriors. Captives were also used for prisoner exchanges. Some fishing societies, like the Tlingit and Haida, had hereditary slavery. Slaves were usually prisoners of war and their children. About a quarter of the population among indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast were slaves.

The first conflicts between Europeans and Indigenous peoples might have happened around 1003 CE. Norsemen tried to settle along the northeastern coast of North America, at places like L'Anse aux Meadows. But the local people, called Skrælings in Norse sagas, fought back fiercely. The Norse eventually left.

Before French settlements in the St. Lawrence River valley, the local Iroquois people were mostly displaced. This was likely due to wars with their neighbors, the Algonquin. The Iroquois League was formed before major European contact, likely between 1450 and 1600. These existing Indigenous alliances became very important to European powers. They helped in the fight for control of North America in the 17th and 18th centuries.

After Europeans arrived, fighting between Indigenous groups became more deadly. This was especially true as tribes got involved in the economic and military rivalries of the European settlers. By the late 17th century, First Nations from the northeastern woodlands, eastern subarctic, and the Métis (people of mixed First Nations and European descent) quickly started using firearms. This replaced their traditional bows. Firearms greatly increased the number of deaths in battles. The uneven spread of guns and horses among tribes also made conflicts much bloodier.

17th Century European Settlements

The French founded Port Royal in 1605. Five years later, the English started their first settlement at Cuper's Cove. By 1706, the French population was about 16,000. It grew slowly for many reasons. This lack of immigration meant New France had only one-tenth of the British population in the Thirteen Colonies by the mid-1700s.

La Salle's explorations gave France a claim to the Mississippi River valley. Here, fur trappers and a few settlers created scattered communities. The French colonies of Acadia and Canada focused mainly on the fur trade. They had limited support from the French monarchy. These colonies grew slowly due to tough geography and climate. The New England Colonies to the south had better locations. They developed a diverse economy and grew quickly from immigration. From 1670, the English also claimed Hudson Bay and its surrounding lands through the Hudson's Bay Company. They also set up colonies and fishing settlements in Newfoundland.

The early military of New France included French Army and Navy soldiers. These were supported by small local volunteer groups called Colonial militia. Most early troops came from France. But as the colony grew, many volunteers were settlers from New France. By the 1750s, most troops were descendants of the original French settlers. Many French-born officers and soldiers stayed in the colony after their service. They helped create a military elite. The French built many forts from Newfoundland to Louisiana. Some were military posts and trading forts.

Anglo-Dutch Wars in North America

The Second Anglo-Dutch War (1665–1667) was a fight between England and the Dutch Republic. It was partly about controlling the seas and trade routes. In 1664, Dutch Admiral Michiel de Ruyter was ordered to attack English ships in the West Indies and at the Newfoundland fisheries. This was in response to English attacks on Dutch trading posts. In June 1665, De Ruyter sailed north from Martinique to Newfoundland. He captured English merchant ships and took the town of St. John's.

During the Third Anglo-Dutch War, the people of St. John's fought off a second Dutch attack in 1673. Christopher Martin, an English merchant captain, defended the city. He used six cannons from his ship and built a defensive wall near Chain Rock. This protected the entrance to the harbor.

Beaver Wars: French and Iroquois Conflicts

The Beaver Wars (also called the French and Iroquois Wars) lasted for almost a century. They ended with the Great Peace of Montreal in 1701. The French, led by Pierre Dugua, Sieur de Mons, founded settlements at Port Royal. Three years later, Samuel de Champlain founded Quebec City. They quickly joined existing Indigenous alliances. This brought them into conflict with other Indigenous groups. Champlain joined a Huron–Algonquin alliance against the Iroquois Confederacy. In the first battle, French firepower quickly scattered a large group of Indigenous warriors.

The Iroquois then changed their tactics. They used their hunting skills and knowledge of the land with firearms from the Dutch. They became very good at guerrilla warfare. Soon, they were a big threat to all but the few fortified cities. The French gave few guns to their Indigenous allies.

For the first hundred years, the main threat to New France came from the Iroquois Confederacy, especially the easternmost Mohawks. Most tribes in the region were French allies. But the Iroquois tribes allied first with the Dutch and then the British. To counter the Iroquois threat, the French government sent the Carignan-Salières Regiment. These were the first professional soldiers in uniform to arrive in what is now Canada. After peace was made, this regiment was disbanded in Canada. The soldiers settled in the St. Lawrence valley. In the late 17th century, they formed the core of the Compagnies Franches de la Marine, the local militia. Later militias were set up on the larger seigneuries land systems.

Civil War in Acadia

In the mid-17th century, Acadia experienced what some historians call a civil war. This war was between Port Royal, led by Governor Charles de Menou d'Aulnay, and present-day Saint John, New Brunswick, led by Governor Charles de Saint-Étienne de la Tour. There were four major battles. La Tour attacked d'Aulnay at Port Royal in 1640. D'Aulnay responded by blockading La Tour's fort at Saint John for five months. La Tour eventually broke the blockade in 1643. La Tour attacked d'Aulnay again at Port Royal in 1643. D'Aulnay and Port Royal finally won the war with the 1645 siege of Saint John. However, after d'Aulnay died in 1650, La Tour returned to power in Acadia.

King William's War: Attacks on Quebec and Newfoundland

During King William's War (1689–1697), Quebec faced a serious threat in 1690. New England colonies sent an expedition led by Sir William Phips to capture Quebec City. This expedition was poorly organized and arrived in mid-October, just before the St. Lawrence River would freeze. When Phips demanded surrender, Governor Frontenac famously replied, "I will answer ... only with the mouths of my cannon and the shots of my muskets." After a failed landing near Quebec City, the English force retreated.

During the war, conflicts in Acadia included battles at Chedabucto, Port Royal, and a naval battle in the Bay of Fundy. The Maliseet people from Meductic on the Saint John River took part in many raids against New England.

In 1695, Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville was ordered to attack English stations along the Atlantic coast of Newfoundland in the Avalon Peninsula campaign. Iberville sailed to Placentia (Plaisance), the French capital of Newfoundland. Both English and French fishermen used the Grand Banks fishery. But the French expedition of 1696 aimed to remove the English from Newfoundland. After burning St. John's, Iberville's Canadians almost completely destroyed English fisheries along Newfoundland's eastern shore.

Small raiding parties attacked villages in remote bays. They burned, looted, and took prisoners. By the end of March 1697, only Bonavista and Carbonear remained in English hands. In four months, Iberville destroyed 36 settlements. At the end of the war, England returned the territory to France in the Treaty of Ryswick.

18th Century Conflicts

In the 18th century, the British and French struggle in Canada grew more intense. The French government spent more money on its North American colonies. They kept expensive garrisons at distant fur trading posts. The defenses of Quebec City were improved. A new fortified town, the fortress of Louisbourg, was built on Cape Breton Island. It was called "Gibraltar of the North."

New France and New England fought three wars in the 18th century. The second and third wars, Queen Anne's War and King George's War, were part of larger European conflicts. The last, the French and Indian War (part of the Seven Years' War), started in the Ohio Valley. French Canadian forces often attacked New England towns and villages. The war also spread to forts along the Hudson Bay shore.

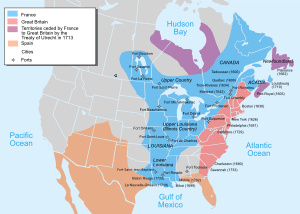

Queen Anne's War and British Conquests

During Queen Anne's War (1702–1713), the British conquered Acadia. A British force captured Port-Royal (now Annapolis Royal) in 1710. In Newfoundland, the French attacked St. John's in 1705 and captured it in 1708. They burned civilian buildings each time. As a result, France had to give control of Newfoundland and mainland Nova Scotia to Britain in the Treaty of Utrecht (1713). This left New Brunswick as disputed territory. Prince Edward Island and Cape Breton Island remained French. British control of Hudson Bay was also guaranteed by the treaty. During Queen Anne's War, battles in Nova Scotia included the Raid on Grand Pré, the Siege of Port Royal (1707), and the Battle of Bloody Creek (1711).

Father Rale's War and Indigenous Rights

During the time leading up to Father Rale's War (also known as Dummer's War), the Mi'kmaq raided the new fort at Canso in 1720. In May 1722, Lieutenant Governor John Doucett took 22 Mi'kmaq hostage at Annapolis Royal. This was to prevent an attack on the capital. In July 1722, the Abenaki and Mi'kmaq created a blockade of Annapolis Royal. They wanted to starve the capital. The Mi'kmaq captured 18 fishing vessels and prisoners from Yarmouth to Canso.

Massachusetts Governor Samuel Shute declared war on the Abenaki on July 22, 1722. Early battles of Father Rale's War happened in Nova Scotia. In July 1724, sixty Mi'kmaq and Maliseets raided Annapolis Royal. The treaty that ended the war was important. For the first time, a European empire formally recognized that its rule over Nova Scotia needed to be negotiated with the Indigenous people. This treaty was even used in a court case in 1999.

King George's War: Louisbourg and Halifax

During King George's War (1744–1748), also called the War of the Austrian Succession, New England militia and the Royal Navy captured Louisbourg in 1745. But the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle (1748) returned Louisbourg to France. This angered the New Englanders. To balance French strength at Louisbourg, the British founded Halifax in 1749. Conflicts in Nova Scotia during this war included the Raid on Canso, the Siege of Annapolis Royal (1744), and the Battle of Grand Pré.

Father Le Loutre’s War: British Expansion

Father Le Loutre's War (1749–1755) was fought in Acadia and Nova Scotia. The British and New Englanders, led by John Gorham and Charles Lawrence, fought against the Mi'kmaq and Acadians. French priest Jean-Louis Le Loutre led the Mi'kmaq and Acadians. The war began when the British established Halifax. As a result, Acadians and Mi'kmaq attacked places like Chignecto, Grand-Pré, and Dartmouth. The French built forts at Saint John, Chignecto, and Fort Gaspareaux. The British responded by attacking the Mi'kmaq and Acadians. They also built new communities like Lunenburg and Lawrencetown. The British built forts in Acadian communities at Windsor, Grand-Pré, and Chignecto.

The Mi’kmaq and Acadians attacked British forts and new settlements. They wanted to slow British settlement and give France time to move Acadians to other French colonies. The war ended after six years with the defeat of the Mi'kmaq, Acadians, and French at the Battle of Fort Beauséjour. During this war, Atlantic Canada saw more people moving, more forts being built, and more troops than ever before. Acadians and Mi'kmaq left Nova Scotia during the Acadian Exodus. They moved to the French colonies of Prince Edward Island and Cape Breton Island.

French and Indian War: The Fall of New France

The last colonial war of the 18th century was the French and Indian War (1754–1763). The British wanted to remove any military threat and cut off supplies to Louisbourg. So, they began deporting the Acadians. The Expulsion of the Acadians started with the Bay of Fundy Campaign in 1755. Over the next nine years, more than 12,000 Acadians were removed from Nova Scotia. Conflicts in the maritime region included the Battle of Fort Beauséjour, the Battle of Petitcodiac, and the Siege of Louisbourg (1758).

In the St. Lawrence and Mohawk areas, the French challenged British claims in the Ohio Country. This land was also claimed by some British colonies. In 1753, the French began building forts in the Ohio Country. In 1755, the British sent two regiments to North America to drive out the French. But French Canadians and First Nations destroyed these forces near Fort Duquesne. War was officially declared in 1756. Six French regiments, led by 44-year-old General Marquis de Montcalm, arrived.

Under Montcalm, the French won several surprising victories. They won at Fort William Henry and at the Battle of Carillon. In June 1758, a British force of 13,000 soldiers, led by Major General Jeffrey Amherst and James Wolfe, captured the Fortress of Louisbourg.

The next year, Wolfe decided to try and capture Quebec City. After several failed landing attempts, Wolfe finally got his army ashore. They formed ranks on the Plains of Abraham on September 12. Montcalm, against his officers' advice, attacked the British with fewer soldiers. In the battle, Wolfe was killed, and Montcalm was mortally wounded. Both sides suffered many casualties. However, in the spring of 1760, the last French General, François Gaston de Lévis, marched from Montreal to Quebec. He defeated the British at the Battle of Sainte-Foy. The French then besieged Quebec. The siege lasted until May 15, when British ships arrived to help the city. Lévis had to retreat.

The British then launched the Montreal Campaign in the summer of 1760. By September, the city surrendered. French resistance ended, and the British Conquest of Canada was complete. This was confirmed by the Treaty of Paris (1763).

American Revolutionary War: Invasions and Raids

With the French threat gone, Britain's American colonies became restless. They didn't like paying taxes to support a large military when there was no clear enemy. They also suspected British motives when the Ohio Valley was set aside for First Nations, instead of being added to British colonies. The American Revolutionary War (1776–1783) began as revolutionaries fought for independence and western lands.

In 1775, the Continental Army invaded the British Province of Quebec. American forces took Montreal and forts in the Richelieu Valley. But attempts to take Quebec City failed. Most French Canadians stayed neutral. After the British sent more troops, a counter-attack pushed American forces back. This ended the military campaign in Quebec.

Throughout the war, American privateers attacked coastal communities. They raided places like Lunenburg, Liverpool, and Annapolis Royal. They also destroyed fisheries in Canso.

To protect against these attacks, the 84th Regiment of Foot (Royal Highland Emigrants) was stationed in forts around Atlantic Canada. Fort Edward (Nova Scotia) in Windsor became a headquarters to stop a possible American land attack on Halifax. There was an American land attack on Nova Scotia at the Battle of Fort Cumberland, followed by the Siege of Saint John (1777).

American privateers captured 225 ships going to or from Nova Scotia ports. In 1781, a French fleet fought a naval battle near Sydney, Nova Scotia. The British captured many American privateers, especially in the naval battle off Halifax in 1782. The Royal Navy used Halifax as a base to attack New England.

The revolutionaries failed to conquer what is now Canada. Many colonists remained loyal to Britain. This led to a split in Britain's North American empire. Many Americans loyal to the Crown, known as United Empire Loyalists, moved north. This greatly increased the English-speaking population of what became British North America. The independent United States formed to the south.

French Revolutionary Wars: Newfoundland Expedition

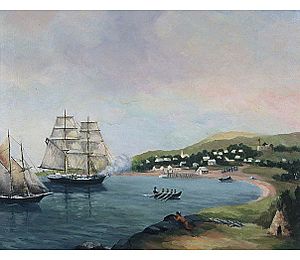

During the War of the First Coalition, French and Spanish fleets sailed to the colony of Newfoundland. The French expedition, led by Rear-Admiral Joseph de Richery, included seven large warships. A Spanish squadron joined them. This combined fleet sailed from Spain.

When the naval squadron was sighted, defenses were prepared at St. John's, Newfoundland, in August 1796. Richery decided not to attack the defended capital. Instead, he moved south to raid undefended settlements, fishing stations, and a military base at Placentia Bay. After the raids, the squadron split. Half raided Saint Pierre and Miquelon, while the other half intercepted fishing fleets off Labrador.

19th Century Conflicts

War of 1812: Defending Canada

After the American Revolution, tensions continued between the United States and the United Kingdom. War broke out in 1812. One reason for the war was British interference with US ships. The Americans did not have a strong navy. So, they planned to invade Canada as a way to attack the British Empire. Americans on the western frontier also hoped an invasion would end British support for Indigenous resistance.

The Americans invaded in July 1812. The war raged along the border of Upper Canada, on land and on the Great Lakes. The British captured Detroit in July and again in October. On July 12, US General William Hull invaded Canada at Windsor. The invasion was quickly stopped, and Hull retreated. This allowed General Isaac Brock to advance on Detroit. He secured the help of Shawnee chief Tecumseh. Brock, though outnumbered, convinced Hull to surrender. This was a major defeat for the Americans. A big American attack across the Niagara frontier was defeated at the Battle of Queenston Heights, where Sir Isaac Brock died.

In 1813, the US retook Detroit. They had successes along Lake Erie, winning the Battle of Lake Erie and the Battle of Moraviantown on October 5. The naval battle gave the US control of lakes Erie and Huron. At Moraviantown, the British lost Tecumseh, a key commander. Further east, the Americans captured and burned York (now Toronto). They also took Fort George at Niagara. However, two American attacks on Montreal were defeated that same year. One was stopped by British soldiers at the Battle of Crysler's Farm. The other was defeated by French Canadian soldiers and militia at the Battle of Châteauguay.

After capturing Washington, DC, in September, British troops burned the White House. But they were pushed back at the Battle of Baltimore. Forces attacking during the Battle of New Orleans were defeated with heavy losses.

During the War of 1812, Nova Scotia helped by buying or building privateer ships. These ships attacked American vessels. The Liverpool Packet from Liverpool, Nova Scotia, captured fifty ships. A famous moment was when HMS Shannon brought the captured American ship USS Chesapeake into Halifax Harbour in 1813. Many American prisoners died at Deadman's Island, Halifax.

Sir Isaac Brock became a Canadian hero. Canada's defense relied on Canadian militia, British troops, the Royal Navy, and Indigenous allies. Neither side can claim total victory. Historians agree that Native Americans were the main losers. The British stopped plans to create a neutral Indigenous state. Tecumseh's alliance fell apart after his death. Indigenous groups no longer posed a major threat to American expansion.

Building Defenses and Rebellions

The fear of another American invasion lasted for fifty years. This was the main reason for keeping a large British military presence in the colony. From the 1820s to the 1840s, many forts were built. The British wanted strong points to defend against an American invasion. These included the Citadels at Quebec City and Citadel Hill in Halifax, and Fort Henry in Kingston.

The Rideau Canal was built for wartime shipping. It allowed ships to travel a northern route from Montreal to Kingston. The usual peacetime route, the St. Lawrence River, was too close to the American border and vulnerable to attack.

Rebellions of 1837

One important action by British forces and Canadian Militia was putting down the Rebellions of 1837. These were two separate rebellions in Lower Canada and Upper Canada. As a result, the Canadas were merged into one colony, the Province of Canada.

The Upper Canada Rebellion was quickly defeated. Attacks the next year by American irregulars were crushed. The Lower Canada Rebellion was a bigger threat. Rebels won at the Battle of St. Denis in November 1837. But two days later, they were defeated at the Battle of Saint-Charles. On December 14, they were finally routed at the Battle of Saint-Eustache.

British Military Withdrawal

By the 1850s, fears of an American invasion lessened. The British began reducing their military presence. The Canadian–American Reciprocity Treaty in 1854 further eased concerns. However, tensions rose again during the American Civil War (1861–65). This peaked with the Trent Affair in 1861. A US gunboat stopped a British ship and removed two Confederate officials. The British government was angry. War seemed possible, so Britain sent more troops to North America, increasing their numbers from 4,000 to 18,000. But war was avoided, and the crisis passed. This was the last major Anglo-American military confrontation in North America. Both sides increasingly saw the benefits of friendly relations. Many Canadians went south to fight in the Civil War, mostly for the Union side.

Britain was also worried about military threats closer to home. They were unhappy paying to keep troops in colonies that, after 1867, became the self-governing Dominion of Canada. So, in 1871, British troops were completely withdrawn from Canada. Only Halifax and Esquimalt kept British garrisons for imperial strategy.

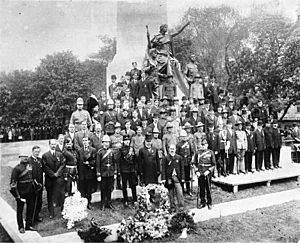

Canadians in British Forces

Before Canadian Confederation, several regiments were formed in the Canadian colonies by the British Army. These included the 40th (the 2nd Somersetshire) Regiment of Foot and the 100th (Prince of Wales's Royal Canadian) Regiment of Foot. Many Nova Scotians fought in the Crimean War. The Welsford-Parker Monument in Halifax is the only Crimean War monument in North America. It is also Canada's fourth oldest war monument, built in 1860. It remembers the Siege of Sevastopol (1854–1855). The first Canadian to receive the Victoria Cross, Alexander Roberts Dunn, served in this war.

During the Indian Rebellion of 1857, William Nelson Hall was the first black Canadian and black Nova Scotian to receive the Victoria Cross. He earned it for his actions in the Siege of Lucknow.

Fenian Raids: Irish-American Invasions

The last invasion of Canada happened during this time. It was not by a US government force, but by a group called the Fenians. The Fenian raids (1866–1871) were carried out by Irish Americans. Most were Union Army veterans from the American Civil War. They believed that by taking Canada, they could force the British government to change its policies in Ireland. The Fenians wrongly thought that Irish Canadians would support them. However, most Irish settlers in Upper Canada were Protestants loyal to the British Crown.

After the Civil War, many in the United States felt anti-British. British-built Confederate warships had caused problems for US trade. Irish-Americans were a large and important group, especially in the Northeastern States. So, the US government generally ignored the Fenians' efforts. The Fenians were allowed to organize and arm themselves. They even recruited in Union Army camps. The Americans did not want to risk war with Britain. They intervened only when the Fenians threatened American neutrality. The Fenians were a serious threat to Canada because they were well-armed Civil War veterans. Despite their failures, the raids influenced Canadian politicians. They were then negotiating the Confederation agreement of 1867.

Canadian Militia in the Late 19th Century

With Confederation in place and British troops gone, Canada became fully responsible for its own defense. The Parliament of Canada passed the Militia Act of 1868. However, it was understood that Britain would send help in a serious emergency. The Royal Navy continued to provide naval defense.

Small professional artillery units were set up at Quebec City and Kingston. In 1883, a third artillery unit was added. Small cavalry and infantry schools were also created. These were meant to form the professional core of the Permanent Active Militia, which would be the main part of Canada's defense. In theory, every able-bodied man aged 18 to 60 could be called to serve in the militia. But in practice, the country's defense relied on volunteers in the Permanent Active Militia. Older, local militia regiments were kept as the Non-Permanent Active Militia.

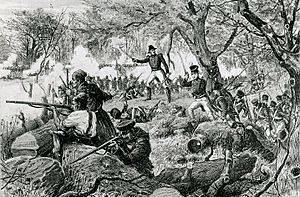

The most important early tests for the militia were expeditions against Louis Riel's rebel forces in western Canada. The Wolseley Expedition, with British and militia forces, restored order after the Red River Rebellion in 1870. The North-West Rebellion in 1885 was the largest military effort on Canadian soil since the War of 1812. It involved battles between the Métis and their First Nations allies against the Militia and North-West Mounted Police.

Government forces eventually won, despite early defeats. The Métis part of the rebellion ended with the Battle of Batoche. The Battle of Loon Lake, which ended this conflict, was the last battle fought on Canadian soil. Government losses were 58 killed and 93 wounded.

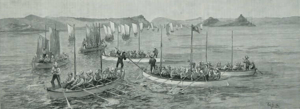

In 1884, Britain asked Canada for help for the first time. They needed experienced boatmen to rescue Major-General Charles Gordon from an uprising in the Sudan. The Canadian government was hesitant. But Governor General Lord Lansdowne recruited a private force of 386 Voyageurs. These were placed under Canadian Militia officers. This force, known as the Nile Voyageurs, served in the Sudan. They became the first Canadian force to serve abroad. Sixteen Voyageurs died during the campaign.

20th Century Conflicts

Boer War: Canada's First Overseas Conflict

The question of Canadian military help for Britain came up again during the Second Boer War (1899–1902) in South Africa. The British asked Canada for help. The Conservative Party strongly supported sending 8,000 troops. English Canadians also largely supported Canadian involvement. However, French Canadians almost all opposed the war. This deeply divided the governing Liberal Party, which needed support from both groups. Prime Minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier was a man of compromise. He worried about conflict between English and French Canadians at home. Laurier initially sent 1,000 soldiers of the Royal Canadian Regiment. Later, other groups were sent, including the privately raised Strathcona's Horse.

Canadian forces missed the early part of the war. But Canadians in South Africa earned praise for leading the charge at the Second Battle of Paardeberg. This was one of the first big victories of the war. At the Battle of Leliefontein in November 1900, three Canadians received the Victoria Cross for protecting a retreating force. In total, over 8,600 Canadians volunteered to fight. About 7,400 Canadians, including many female nurses, served in South Africa. Of these, 224 died, 252 were wounded, and several received the Victoria Cross.

Growth of the Canadian Military

From 1763 until Canada's Confederation in 1867, the British Army was Canada's main defense. But many Canadians served with the British in various wars. As British troops left Canada in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the Militia became more important. In 1883, the Canadian government created its first permanent military forces. After Canada joined the Second Boer War, there was a debate about whether Canada should have its own army. As a result, Canada gained its own technical and support branches. In 1904, a Canadian Chief of the General Staff replaced the British commander. New "corps" were created, including engineers, signals, and medical services.

Canada had a small fishing protection force, but relied on Britain for naval defense. Britain was in an arms race with Germany. In 1908, Britain asked its colonies for help with the navy. The Conservative Party argued that Canada should just give money to the British Navy. Some French-Canadian nationalists felt no aid should be sent. Others wanted an independent Canadian navy that could help Britain when needed.

Prime Minister Laurier chose a compromise. The Canadian Naval Service was created in 1910. It was named the Royal Canadian Navy in August 1911. To please imperialists, the Naval Service Act said the fleet could be given to the British in an emergency. This part of the bill was strongly opposed by Quebec nationalist Henri Bourassa. The bill aimed to build a navy of five cruisers and six destroyers. The first two ships, Niobe and Rainbow, were older vessels bought from the British. After the Conservatives won the 1911 election, the navy received less money. But it grew greatly during the First World War.

First World War: Canada's Major Contribution

On August 4, 1914, Britain declared war on Germany, starting the First World War (1914–1918). This automatically brought Canada into the war. However, the Canadian government could decide how much to be involved. The Militia was not called up. Instead, an independent Canadian Expeditionary Force was created. Canadian military achievements during the First World War include the battles of the Somme, Vimy, and Passchendaele. These were later known as "Canada's Hundred Days".

The Canadian Corps was formed in September 1915. It grew with the addition of the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th Canadian Divisions. A 5th Division was started but later broken up to reinforce the others. Although the corps was under British command, Canadian leaders wanted it to fight as a single unit. Plans for a second Canadian corps were dropped. A difficult national discussion about conscription (forced military service) began.

Most other major countries had started conscription due to heavy casualties. Sir Robert Borden wanted to keep Canada's military contribution strong. The Military Service Act was passed. While English Canada supported conscription, it was very unpopular in Quebec. The Conscription Crisis of 1917 showed the deep divisions between French and English-speaking Canadians. In June 1918, a German submarine sank a Canadian hospital ship, HMHS Llandovery Castle. This was the most significant Canadian naval disaster of the war. In the later stages of the war, the Canadian Corps was one of the most effective forces on the Western Front.

For a nation of eight million people, Canada's war effort was remarkable. A total of 619,636 Canadians served. Of these, 59,544 were killed and 154,361 were wounded. Canadian sacrifices are remembered at eight memorials in France and Belgium. The Vimy Memorial and the Saint Julien Memorial are unique. The others are granite monuments. There are also memorials for Newfoundland soldiers, who did not join Canada until 1949. The war's impact led to many war memorials being built in Canada. The Canadian National War Memorial in Ottawa was unveiled in 1939. It now honors Canadian war dead from several conflicts.

In 1919, Canada sent a Canadian Siberian Expeditionary Force to help in the Allied intervention in the Russian Civil War. Most of these troops were in Vladivostok and saw little fighting before they left.

Birth of the Canadian Air Force

The First World War led to the creation of Canada's air force. At the start of the war, Canada had no independent air force. Many Canadians flew with the British Royal Flying Corps and Royal Naval Air Service. In 1914, the Canadian government approved the Canadian Aviation Corps. It was meant to go to Europe but was disbanded in 1915. A second attempt was made in 1918. Two Canadian squadrons were formed by the British Air Ministry in Europe. The Canadian government took control, forming the Canadian Air Force. This force never saw combat and was disbanded by 1921.

In the 1920s, the British government encouraged Canada to create a peacetime air force. They provided surplus aircraft. In 1920, a new Canadian Air Force (CAF) was formed as a part-time service. It provided flying training. After a reorganization, the CAF became responsible for all flying in Canada, including civil aviation. In April 1924, the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) was created. The Second World War would make the RCAF a truly military service.

Spanish Civil War: Canadian Volunteers

The Mackenzie–Papineau Battalion was a volunteer unit. It was not authorized by the Canadian government. It fought for the Republican side in the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939). The first Canadians in the conflict mainly joined US battalions. By summer 1937, about 1,200 Canadians were involved. They first fought at the Battle of Jarama near Madrid. Over the next year, Canadians fought in three major battles: Battle of Teruel, Aragon Offensive, and Battle of the Ebro. Of the 1,546 Canadians who fought in Spain, 721 were killed. It is said that no other country sent a greater proportion of its people as volunteers to Spain than Canada.

Second World War: Global Effort

The Second World War (1939–1945) began after Nazi Germany invaded Poland on September 1, 1939. Canada's parliament supported the government's decision to declare war on Germany on September 10. This was one week after the United Kingdom and France. Canadian airmen played a small but important role in the Battle of Britain. The Royal Canadian Navy and Canadian merchant marine were crucial in the Battle of the Atlantic. C Force, two Canadian infantry battalions, were involved in the failed defense of Hong Kong. Troops of the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division also played a leading role in the disastrous Dieppe Raid in August 1942. The 1st Canadian Infantry Division and tanks landed on Sicily in July 1943. After a 38-day campaign, they took part in the successful Allied invasion of Italy. Canadian forces were important in the long advance north through Italy.

On June 6, 1944, the 3rd Canadian Division landed on Juno Beach during the Battle of Normandy. Canadian airborne troops also landed behind the beaches earlier that day. By the end of the day, Canadians had pushed further inland than any of the other five invasion forces. Canada played an important role in the fighting in Normandy. The 2nd Canadian Infantry Division arrived in July, and the 4th Canadian Armoured Division in August. For the first time, Canada had its own army headquarters. In the Battle of the Scheldt, the First Canadian Army defeated German forces at great cost. This helped open Antwerp to Allied shipping. The First Canadian Army fought in two more large campaigns: the Rhineland in 1945 and battles across the Rhine River. The I Canadian Corps returned from Italy in early 1945. As part of a reunited First Canadian Army, it helped liberate The Netherlands and invade Germany.

RCAF airmen served with British fighter and bomber squadrons. They were key in the Battle of Britain, anti-submarine warfare during the Battle of the Atlantic, and bombing campaigns against Germany. Even though many RCAF personnel served with the RAF, No. 6 Group of RAF Bomber Command was made entirely of RCAF squadrons. Canadian air force personnel also supported Allied forces during the Battle of Normandy and later campaigns in Europe. To free up male RCAF personnel for active duty, the Royal Canadian Air Force Women's Division was formed in 1941. By the end of the war, the RCAF was the fourth largest Allied air force. A similar group, the Canadian Women's Army Corps, was created for the army.

Many thousands of Canadians also served with the Canadian Merchant Navy. Out of a population of about 11.5 million, 1.1 million Canadians served in the armed forces. In all, more than 45,000 died, and 55,000 were wounded. The Conscription Crisis of 1944 affected unity between French and English-speaking Canadians at home. However, it was not as politically difficult as the First World War crisis. Canada had a benefits program for its Second World War veterans, similar to the American G.I. Bill.

Cold War Era: Global Commitments

Soon after the Second World War, the Cold War (1946–1991) began. The Cold War is often said to have started with the 1945 defection of a Soviet spy in Ottawa, Igor Gouzenko. As a founding member of NATO and a signer of the NORAD treaty with the US, Canada joined the alliance against the Communist bloc. Canadian troops were stationed in Germany throughout the Cold War. Canada also worked with the Americans to build defenses against Soviet attack, like the DEW Line. As a middle power, Canada knew it could do little militarily on its own. So, it adopted a policy of multilateralism. This meant Canada's military efforts would be part of larger international groups. This led Canada to stay out of some wars, like the Vietnam War and the Second Iraq War, even though close allies participated. However, Canada did provide indirect support, and Canadian citizens served in foreign armies in both conflicts.

Canadian Forces in Europe

Canada kept a mechanized infantry brigade in West Germany from the 1950s to the 1990s. This was part of Canada's NATO commitments. This brigade was kept at full strength and had Canada's most advanced weapons. It was expected to move quickly if the Warsaw Pact invaded the west. The Royal Canadian Air Force also set up No. 1 Air Division in the early 1950s for NATO air defense in Europe.

Korean War: A "Forgotten War"

After the Second World War, Canada quickly reduced its military. When the Korean War (1950–1953) started, Canada needed several months to build up its forces. It eventually became part of British Commonwealth Forces Korea. Canadian land forces missed most of the early fighting. They arrived in 1951, when the war had largely become a stalemate.

Canadian troops fought as part of the 1st Commonwealth Division. They distinguished themselves at the Battle of Kapyong and other land battles. HMCS Haida and other Royal Canadian Navy ships served in the Korean War. The Royal Canadian Air Force did not have a combat role in Korea. But twenty-two RCAF fighter pilots flew with the USAF. The RCAF also transported personnel and supplies.

Canada sent 26,791 troops to Korea. There were 1,558 Canadian casualties, including 516 dead. Korea is often called "The Forgotten War" because it is overshadowed by Canada's contributions to the two world wars. Canada signed the 1953 armistice. It did not keep troops in South Korea after 1955.

Unification of the Forces

In 1964, the Canadian government decided to merge the Royal Canadian Air Force, the Royal Canadian Navy, and the Canadian Army. This created the Canadian Armed Forces. The goal was to save money and improve efficiency. Minister of National Defence Paul Hellyer said in 1966 that the merger would help Canada meet future military needs. It would also make Canada a leader in military organization. Unification was completed on February 1, 1968.

October Crisis: Troops in Montreal

The October Crisis was a series of events in October 1970. Members of the Front de libération du Québec (FLQ) kidnapped government officials in Quebec, mainly around Montreal. During this domestic terrorist crisis, Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau was asked how far he would go to solve the problem. He famously replied, "Just watch me". Three days later, on October 16, the government used the War Measures Act. This was the only time it was used in peacetime in Canada. The act led to 12,500 Canadian Forces troops being sent across Quebec, with 7,500 in Montreal.

Vietnam War: Non-Belligerent Role

Canada did not fight in the Vietnam War (1955–1975). It was officially a "non-belligerent" nation. Canadian Forces involvement was limited to a small group in 1973. They helped enforce the Paris Peace Accords. The war still affected Canadians. About 30,000 Canadians volunteered to fight in Southeast Asia. This was opposite to the movement of American draft-dodgers to Canada. Among the volunteers were fifty Mohawks from the Kahnawake reserve near Montreal. 110 Canadians died in Vietnam, and seven are still listed as Missing in Action.

Post–Cold War Era: New Roles

Oka Crisis: Land Dispute

The Oka Crisis was a land dispute between Mohawk people and the town of Oka in Quebec. It began on July 11, 1990, and lasted until September 26. On August 8, Quebec premier Robert Bourassa asked for military support. This right is available to provincial governments. It was used after one police officer and two Mohawk were killed. The Chief of the Defence Staff, General John de Chastelain, sent Quebec-based troops to help. During Operation Salon, 2,500 regular and reserve troops were called up. Troops and vehicles gathered around Oka and Montreal. Reconnaissance aircraft flew over Mohawk territory to gather information. Despite high tensions, no shots were fired between the military and First Nations. On September 1, a photographer took a famous picture called Face to Face. It showed men staring each other down.

Gulf War: Coalition Operations

Canada was one of the first nations to condemn Iraq's invasion of Kuwait. It quickly joined the US-led coalition. In August 1990, Prime Minister Brian Mulroney sent a Naval Task Group. The destroyers HMCS Terra Nova and HMCS Athabaskan joined the force. They were supported by the supply ship HMCS Protecteur. The Canadian group led the coalition's naval logistics in the Persian Gulf. A fourth ship, HMCS Huron, arrived after the fighting ended. It was the first allied ship to visit Kuwait.

After the UN allowed force against Iraq, the Canadian Forces sent a CF-18 Hornet and Sikorsky CH-124 Sea King squadron. They also sent a field hospital for casualties. When the air war began, Canada's CF-18s joined the coalition. They provided air cover and attacked ground targets. This was the first time since the Korean War that the Canadian military took part in offensive combat. The only CF-18 Hornet to record an official victory was involved in the Battle of Bubiyan against the Iraqi Navy.

Yugoslav Wars: Peacekeeping and Combat

Canada's forces were part of UNPROFOR, a UN peacekeeping force. They served in Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina during the Yugoslav wars in the 1990s. Operation Medak pocket was the largest battle fought by Canadian forces since the Korean War. The Canadian government says Canadian forces clashed with the Croatian Army. 27 Croatian soldiers were reported killed. In 2002, the 2nd Battalion Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry Battle Group received an award. It was for their "heroic and professional mission during the Medak Pocket Operation."

Somali Civil War: Humanitarian Mission and Controversy

During the Somali Civil War, Prime Minister Brian Mulroney committed Canada to UNOSOM I. This was after United Nations Security Council Resolution 751. UNOSOM I was the first part of the UN's effort to provide security and humanitarian aid in Somalia. Canadian forces, under Operation Deliverance, joined the American-led Operation Restore Hope. In May 1993, the operation came under UN command and was renamed UNOSOM II. By its end, the mission became a political disaster for the Canadian Forces. During the mission, Canadian soldiers killed a Somali teenager. This led to the Somalia Affair. After an inquiry, the elite Canadian Airborne Regiment was disbanded. The reputation of the Canadian Forces suffered within Canada.

Domestic Operations: Floods and Ice Storms

The 1997 Red River flood was the worst flood of the Red River of the North since 1826. It affected North Dakota and Manitoba. A "public welfare emergency" was declared. Over 8,500 military personnel were sent to Manitoba. They helped with evacuations, building dikes, and other flood-fighting efforts. This was the largest single Canadian troop deployment since the Korean War. Operation Assistance was a "public relations bonanza" for the military. When a military convoy left Winnipeg, thousands of civilians cheered for them.

"Operation Recuperation" was in response to the North American ice storm of 1998. This massive storm hit from Lake Huron to southern Quebec and parts of the US. Roads were blocked by snow, fallen trees, and ice. Emergency vehicles could barely move. On January 7, New Brunswick, Ontario, and Quebec asked for help from the Canadian Forces. Operation Recuperation began on January 8 with 16,000 troops deployed. It was the largest deployment of troops ever on Canadian soil for a natural disaster. It was also the largest operational deployment of Canadian military personnel since the Korean War.

21st Century Operations

Afghanistan War: Fighting Terrorism

Canada joined a US-led group in the 2001 attack on Afghanistan. This war was a response to the 9/11 terrorist attacks. Its goal was to defeat the Taliban government and Al-Qaeda. Canada sent special forces and ground troops. In this war, a Canadian sniper set a world record for the longest-distance kill. In early 2002, Canadian JTF2 troops handed over shackled Taliban prisoners to US forces. This sparked a debate about the Geneva Convention. In November 2005, Canadian military involvement shifted to Operation Archer in Kandahar. On May 17, 2006, Captain Nichola Goddard became Canada's first female combat casualty.

One notable Canadian operation in Afghanistan was Operation Medusa. This included the second Battle of Panjwaii. At the end of 2006, the Canadian soldier was chosen as the Canadian Newsmaker of the Year because of the war. On November 27, 2010, the 1st Battalion of the Royal 22e Régiment took over operations in Kandahar. This was the final rotation before Canada's withdrawal. In July 2011, a small group of Canadian troops transferred to the NATO Training Mission-Afghanistan. They continued training the Afghan National Army and Afghan National Police until 2014.

British Columbia Forest Fires

"Operation Peregrine" was a domestic military operation from August 3 to September 16, 2003. In early August 2003, British Columbia was overwhelmed by over 800 forest fires. Provincial fire services were stretched thin. Tens of thousands of people had to leave their homes. The provincial government asked for federal help. Within days, over 2,200 Canadian Forces personnel were called up. The operation lasted 45 days. At its peak, more than 2,600 military personnel were involved. It was the Canadian Forces' third-largest recent domestic deployment. The others were "Operation Recuperation" for the 1998 ice storm and "Operation Assistance" for the 1997 Red River flood.

Iraq War: Indirect Support

The Iraq War (2003–2011) began on March 20, 2003. The Canadian government did not officially declare war against Iraq. However, Canada's involvement and relationship with the US changed during the war. The Canadian Forces helped with ship escort duties. They also expanded their role in Combined Task Force 151 to free up American naval assets. About a hundred Canadian exchange officers, serving with American units, took part in the invasion of Iraq. There were many protests and counter-protests in Canada related to the conflict. Some United States Military members sought refuge in Canada after deserting their posts to avoid deployment to Iraq.

Libyan Civil War: No-Fly Zone

On March 19, 2011, a group of countries began a military intervention in Libya. This was to carry out United Nations Security Council Resolution 1973 in response to the 2011 Libyan civil war. Canada contributed naval and air assets as part of Operation Mobile. NATO took control of military actions on March 25, with RCAF Lieutenant General Charles Bouchard in command. A no-fly zone was put in place to stop forces loyal to Muammar Gaddafi from attacking civilians from the air. The military intervention was enforced by NATO's Operation Unified Protector. It included an arms embargo, a no-fly zone, and a mandate to protect Libyan civilians. On October 28, 2011, Prime Minister Stephen Harper announced that the NATO mission had ended successfully.

Mali Conflict: Transport and Security

Starting in early 2012, several rebel groups in Mali began taking over the country. In January 2013, Mali asked France for help. In December, the UN approved an African intervention. France then asked its NATO allies to get involved. Canada joined by helping transport troops with a C-17 Globemaster. After this, twenty-four Joint Task Force 2 members entered the country. They secured the Canadian embassy in the capital, Bamako. A ceasefire agreement was signed in February 2015. However, occasional terrorist attacks still happen.

Military Intervention Against ISIL

Operation Impact is Canada's contribution to the military intervention against the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant. It began in September 2014. The first Canadian airstrike against an Islamic State target happened on November 2. CF-18s successfully destroyed heavy engineering equipment. This equipment was used to divert the Euphrates River near Fallujah. In October, then Prime Minister-designate Justin Trudeau told President Barack Obama that Canada planned to withdraw its fighter aircraft. However, it would keep its ground forces in Iraq and Syria.

Recent Military Spending

The Constitution of Canada gives the federal government responsibility for national defense. Spending is outlined in the federal budget. For the 2007–2010 fiscal year, defense spending was CA$6.15 billion. This was 1.4 percent of the country's GDP. This funding was increased in 2005 with an extra CA$12.5 billion over five years. There was also a commitment to increase regular force troops by 5,000 and primary reserves by 4,500. In 2010, an additional CA$5.3 billion was provided over five years. This allowed for 13,000 more regular force members and 10,000 more primary reserve personnel. It also included CA$17.1 billion for new trucks, transport aircraft, helicopters, and joint support ships. In July 2010, the largest purchase in Canadian military history was announced. It was CA$9 billion for 65 F-35 fighters. Canada helped develop the F-35 and invested over CA$168 million in the program. In 2010, Canada's military spending was about CA$122.5 billion.

Canadian Crown and the Forces

The Canadian Forces get many traditions and symbols from the UK military. This includes royal elements. Modern symbols and rituals also show Canada and the Canadian monarchy. Members of Canada's Royal Family continue their two-century-old practice. They maintain personal relationships with the forces' divisions and regiments. The military has developed special rules around this. The role of the Canadian Crown in the Canadian Forces is set by law. The National Defence Act states that "the Canadian Forces are the armed forces of Her Majesty raised by Canada." The Constitution Act, 1867 gives Command-in-Chief of those forces to the monarch.

All honors in Canada come from the country's monarch. A complex system of orders, decorations, and medals honors Canadians. The Victoria Cross, Order of Military Merit, Cross of Valour, Star of Courage, and Medal of Bravery are some military awards. The Victoria Cross was given to 94 Canadians and 2 Newfoundlanders between 1856 and 1993. No Canadian has received either honor since 1945.

During the unification of the forces in the 1960s, the "royal designations" of the navy and air force were dropped. On August 16, 2011, the Government of Canada announced changes. "Air Command" became the Royal Canadian Air Force again. "Land Command" became the Canadian Army. "Maritime Command" became the Royal Canadian Navy again. This change was made to reflect Canada's military heritage. It also aligns Canada with other Commonwealth of Nations countries that use royal designations.

Peacekeeping: Canada's Global Role

Canada's commitment to working with many countries has led to strong support for peacekeeping efforts. Canada's peacekeeping role has been a major part of its global image. Before Canada's role in the Suez Crisis, many saw Canada as unimportant in global issues. Canada's successful role in that conflict gave it credibility. It established Canada as a nation fighting for the "common good" of all nations. Canada participated in every UN peacekeeping effort from its start until 1989. Since 1995, Canada's direct involvement in UN peacekeeping has greatly decreased. In July 2006, Canada ranked 51st in UN peacekeepers, contributing 130 peacekeepers out of over 70,000. This number decreased because Canada started directing its participation to UN-sanctioned military operations through NATO, rather than directly to the UN.

Canadian Nobel Peace Prize winner Lester B. Pearson is considered the father of modern peacekeeping. Pearson was a prominent figure in the United Nations. In 1956, during the Suez Crisis, Pearson and Canada were caught between their closest allies. Pearson proposed to the security council that a United Nations police force be created. This would prevent further conflict and allow countries to find a solution. Pearson's proposal and offer of 1,000 Canadian soldiers was a brilliant political move that prevented another war.

The first Canadian peacekeeping mission was in 1948, even before the formal UN system. It was a mission to the second Kashmir conflict. Other important missions include those in Cyprus, Congo, Somalia, and Yugoslavia. There were also observation missions in the Sinai Peninsula and Golan Heights. The loss of nine Canadian peacekeepers when their Buffalo 461 was shot down over Syria in 1974 is the largest single loss of life in Canadian peacekeeping history. In 1988, the Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to United Nations peacekeepers. This inspired the creation of the Canadian Peacekeeping Service Medal. It recognizes Canadians who contributed to peace on certain missions.

See also

In Spanish: Historia militar de Canadá para niños

In Spanish: Historia militar de Canadá para niños

| Laphonza Butler |

| Daisy Bates |

| Elizabeth Piper Ensley |