Peacekeeping facts for kids

Peacekeeping is all about helping countries find lasting peace, especially after a conflict. It involves different activities, often with military, police, and civilian people working together. Studies show that peacekeeping helps save lives and lowers the chance of wars starting again.

The United Nations (UN) is a big group of countries working for peace. They often send peacekeepers to places where fighting has stopped. These peacekeepers watch over peace agreements and help former fighters. They might help build trust, share power, support elections, and strengthen fair laws. They also help with economic and social development. UN peacekeepers are often called Blue Berets or Blue Helmets because of their light blue hats or helmets. They can be soldiers, police officers, or civilians.

Other groups also do peacekeeping missions, not just the UN. For example, NATO has a mission in Kosovo. The Multinational Force and Observers work in the Sinai Peninsula. The European Union and the African Union also organize peacekeeping efforts.

Under international law, peacekeepers are considered neutral. This means they don't take sides in a conflict. They should always be protected from attacks.

Contents

What are Peacekeeping Operations?

UN Peacekeeping Missions Explained

Peacekeeping missions come in different types. A researcher named Page Fortna described four main kinds. How a mission works depends on its official rules, called its "mandate."

Chapter VI and Chapter VII Missions

Most missions are "consent-based," meaning they need permission from the groups fighting. These are called "Chapter VI" missions. If they lose permission, peacekeepers must leave. Other missions are "Chapter VII" missions. These do not always need permission. If permission is lost, they can still stay.

- Observation Missions: These are small groups of military or civilian observers. They watch over cease-fires or troop withdrawals. They are usually unarmed. Their main job is to watch and report what is happening. They don't have the power to stop fighting if agreements are broken. Examples include UNAVEM II in Angola and MINURSO in the Western Sahara.

- Interpositional Missions: Also known as traditional peacekeeping, these are larger groups of lightly armed troops. They act as a barrier between fighting groups after a conflict. They create a buffer zone and check if both sides follow the cease-fire rules. Examples include UNAVEM III in Angola and MINUGUA in Guatemala.

- Multidimensional Missions: These missions involve military and police personnel. They work to put strong peace agreements into action. Besides observing or separating groups, they do many other tasks. These can include supervising elections, reforming police forces, building new government structures, and helping with economic growth. Examples are UNTAG in Namibia and ONUSAL in El Salvador.

- Peace Enforcement Missions: These are Chapter VII missions. They do not need permission from the fighting groups. They are multidimensional, with both civilian and military staff. The military force is large and well-equipped. They are allowed to use force for more than just self-defense. Examples include ECOMOG in West Africa and NATO operations in Bosnia.

UN Missions During and After the Cold War

During the Cold War, peacekeeping mostly meant separating fighting groups. Peacekeepers were sent after wars between countries. They acted as a buffer and made sure peace agreements were followed. These missions needed permission from the countries involved. Observers were often unarmed, like UNTSO in the Middle East. Some were armed, like UNEF-I during the Suez Crisis. They were usually very successful.

After the Cold War, the UN started a more complex approach. In 1992, UN Secretary-General Boutros Boutros-Ghali wrote a report called An Agenda for Peace. It described new ways the UN could help. This included preventing problems, enforcing peace, making peace, keeping peace, and rebuilding after conflict.

Goals of UN Missions

Michael Doyle and Nicolas Sambanis explained the report's ideas. They said the UN aims to prevent violence and build lasting peace.

- Peace Enforcement: This means acting with or without permission from fighting groups. The goal is to make sure peace treaties or cease-fires are kept. Forces are usually heavily armed.

- Peace-making: This involves helping fighting groups find a peaceful solution. The UN offers mediation and other ways to talk things out.

- Peacekeeping: This is when lightly armed UN personnel are sent to an area. They have permission from the fighting groups. Their job is to build trust and check on agreements. Diplomats also keep working for a full and lasting peace.

- Post-Conflict Reconstruction: This aims to develop economic and social cooperation. It helps mend relationships between former enemies. Building up society, politics, and the economy can prevent future violence. This helps create strong, lasting peace.

Peacekeeping also involves working with non-governmental organizations (NGOs). This helps protect important cultural sites. The UN has been protecting cultural heritage since 2012. For example, in 2019, the UN mission UNIFIL worked with Blue Shield International to protect UNESCO World Heritage sites in Lebanon. Protecting cultural property helps a city or country develop peacefully. As Karl von Habsburg of Blue Shield International explained, destroying culture can make people feel lost and force them to flee their homes.

Peacekeeping by Other Organizations

Not all international peacekeeping forces are directly controlled by the United Nations. In 1981, Israel and Egypt agreed to form the Multinational Force and Observers. This group still watches over the Sinai Peninsula.

The African Union (AU) is building its own system for peace and security in Africa. This system aims to enforce peace on the continent. If there's a genocide or serious human rights violations, an AU mission could be sent. This could happen even if the country's government doesn't want it, as long as the AU General Assembly approves. The Economic Community of West African States has also started several peacekeeping missions in its member countries.

Unarmed Civilian Peacekeeping (UCP) involves civilian people. They use non-violent methods to protect civilians in conflict zones. They also support efforts to build lasting peace. These methods include staying with people, being present in dangerous areas, stopping rumors, and helping communities feel safe.

A Brief History of Peacekeeping

How Peacekeeping Started

United Nations Peacekeeping began in 1948. The United Nations Security Council sent unarmed military observers to the Middle East. Their job was to watch over the agreement signed between Israel and its Arab neighbors after the 1948 Arab–Israeli War. This mission was called the United Nations Truce Supervision Organization (UNTSO), and it is still working today.

Cold War Peacekeeping Missions

After India and Pakistan became independent in 1947, fighting broke out. In 1948, the Security Council created the United Nations Commission for India and Pakistan (UNCIP). Its goal was to help India and Pakistan solve their dispute over Kashmir. This mission also watched over a cease-fire. Today, this mission continues as the United Nations Military Observer Group in India and Pakistan (UNMOGIP).

Since 1948, 69 peacekeeping operations have been approved around the world. Most of these started after the Cold War. Between 1988 and 1998, 35 new UN operations began. This was a big increase compared to earlier years.

The first armed UN intervention happened after the Suez Crisis in 1956. The United Nations Emergency Force (UNEF-1) was the first UN peacekeeping force. It worked from 1956 to 1967. Its job was to stop fighting between Egypt, the United Kingdom, France, and Israel. It also oversaw the withdrawal of troops. After that, UNEF acted as a buffer between Egyptian and Israeli forces.

Soon after, the United Nations Operation in the Congo (ONUC) started in 1960. At its busiest, it had over 20,000 military personnel. Sadly, 250 UN staff died, including Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld. ONUC helped ensure Belgian forces left the Congo. It also helped keep law and order and provided training. ONUC also worked to keep the Congo's territory whole.

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, the UN created many short-term missions. These included missions in the Dominican Republic and West New Guinea. Longer-term operations were also set up, like the UN Peacekeeping Force in Cyprus (UNFICYP) and the UN Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL).

Peacekeeping Since 1991

Experiences during the Yugoslav Wars, like the Srebrenica Massacre, led to new ideas. The United Nations Peacebuilding Commission was created to help build lasting peace. It focuses on things like elections. In 2013, the U.N. Security Council passed Resolution 2122. This resolution called for more women to be involved in peace talks and peacekeeping missions. It also asked for more information on how conflicts affect women.

Studies show that peacekeeping missions are often sent to places where peace is hardest to achieve. But even in these tough spots, peacekeepers help. They make peace more likely to last.

Who Participates in Peacekeeping?

Countries That Send Peacekeepers

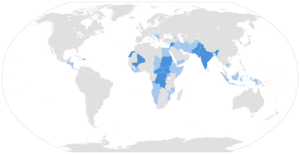

The United Nations Charter says that all UN member countries should help keep peace and security. Since 1948, about 130 nations have sent military and police personnel. It's thought that up to one million soldiers, police, and civilians have served under the UN flag. As of September 2021, 122 countries were contributing about 76,000 people.

Most peacekeepers come from developing countries. The top ten countries sending troops (including police and military experts) in October 2021 were Bangladesh, Nepal, India, Rwanda, Ethiopia, Pakistan, Egypt, Indonesia, Ghana, and China. More than 14,000 civilians also work in peacekeeping. They are experts in law, medicine, education, and technology.

Sadly, many peacekeepers have died while serving. As of September 2021, 4,147 people from over 100 countries have been killed. India has lost the most peacekeepers, followed by Bangladesh and Pakistan. On average, 56 peacekeepers have died each year since 1948. This number has almost doubled since 2001.

Developing nations, mostly from the Global South, provide most peacekeepers. Thomas G. Weiss and Giovanna Kuele explain three reasons for this: regional interests, prestige, and money. African countries send the most peacekeepers. Many African peacekeepers serve on missions in Africa. For example, almost all Ethiopian peacekeepers are in nearby Sudan and South Sudan. Being a peacekeeper contributor also gives countries international respect. It can help them be seen as a great power, like Brazil and India.

Finally, sending peacekeepers can bring money to poorer countries. Countries get paid for each peacekeeper they send. This includes money for pay, allowances, clothing, and equipment. This financial help can be very attractive for soldiers and developing nations. Only about 4.5% of UN peacekeepers come from the European Union. Less than one percent come from the United States.

Women in Peacekeeping

Security Council Resolution 1325 was a big step for the UN. It aimed to include women as active and equal partners in preventing conflicts and building peace. It stressed how important it is for women to be fully involved in all peace efforts.

In 2013, the U.N. Security Council passed Resolution 2122. This resolution called for more women to take part in peace talks and peacekeeping missions. It also asked for more information on how armed conflicts affect women. The Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) also said that countries must protect women's rights during and after conflicts.

As of July 2016, women serve in every UN peacekeeping mission. They work as troops, police, or civilian staff. In 1993, women made up only 1% of uniformed personnel. By 2020, women were 4.8% of military personnel and 10.9% of police personnel. The UN wants countries to send at least 20% women for police officer jobs. In June 2023, women made up 7.3% of all military personnel in UN peace operations. This number is still growing.

How Peacekeeping Helps

Studies show strong evidence that peacekeeping helps increase peace. According to Page Fortna, peacekeepers greatly reduce the risk of war starting again. More peacekeepers also mean fewer deaths in battles and fewer civilian deaths. One study estimated that a strong UN peacekeeping policy could reduce global conflicts by two-thirds.

Peacekeeping can stop wars from spreading to other countries. Having more peacekeepers on the ground also seems to lead to less violence against civilians. Peace operations have sometimes successfully managed countries during transitions.

A 2018 study found that peacekeeping reduces how bad civil wars are. When peacekeeping is combined with mediation, the effect is even greater. There is also evidence that promising to send peacekeepers can help international groups bring fighters to the negotiation table. It can also increase the chance they will agree to a cease-fire.

Page Fortna's research shows that UN peacekeepers have a real impact on lasting peace. Even though peacekeepers are sent to the toughest places, their presence reduces the risk of renewed violence by at least 55-60%. Some estimates say it could be as high as 75-85%. This shows that peacekeeping is a very effective tool for ensuring lasting peace.

Other studies show different success rates for peacekeeping missions, from 31% to 85%. A 2020 study found that non-UN peacekeeping missions are just as effective as UN missions. Another study from 2020 found that peacekeeping successfully protected civilians. A 2021 study showed that UN peacekeeping in South Sudan had a positive effect on the local economy.

Factors for Lasting Peace

Many things can make it harder for peace to last. These include hidden information about how strong each side is. Also, if a rebel group makes money from illegal activities like selling diamonds, it increases the chance of violence starting again. The length and cost of a war also matter.

One of the biggest factors for lasting peace is whether one side clearly won the war. According to Fortna's research, civil wars where one side wins have about an 85-90% lower chance of starting again. Peace treaties also reduce the risk by 60-70%.

If a group is funded by illegal trade, there's a much higher chance of violence starting again. It can be two to three-and-a-half times more likely.

Impacts on Peacekeepers Themselves

Effects on Individual Peacekeepers

Studies of peacekeeping soldiers show both good and bad effects. A study of US Army soldiers in Bosnia found that 77% reported some positive experiences. But 63% reported negative ones. Peacekeepers face dangers from fighting groups and unfamiliar climates. This can lead to mental health problems. Having a parent on a mission abroad for a long time can also be stressful for their families.

Some people worry that peacekeeping might make troops less ready for full combat. This is because peacekeeping missions are very different from fighting a war.

See also

- Bangladesh UN Peacekeeping Force

- Canadian peacekeeping

- List of United Nations peacekeeping missions

- List of countries by number of UN peacekeepers

- List of countries where UN peacekeepers are currently deployed

- List of non-UN peacekeeping missions

- Multinational Force and Observers

- Military operations other than war

- Temporary International Presence in Hebron

- Timeline of UN peacekeeping missions