Canada in World War I facts for kids

The military history of Canada during World War I began on August 4, 1914. This was when the United Kingdom declared war on Germany. Because Canada was a British Dominion, this declaration automatically brought Canada into the First World War (1914–1918). However, the Canadian government could decide how much it would be involved. On August 4, 1914, Canada's Governor General officially declared war on Germany. Instead of using the existing army, a new group called the Canadian Expeditionary Force was created.

Canada's efforts and sacrifices in the Great War changed its history. They helped Canada become more independent. But they also created a big disagreement between French and English-speaking Canadians. For the first time, Canadian forces fought as a separate group. They were first led by a British commander, but later by a Canadian. Key Canadian achievements happened during the Somme, Vimy Ridge, and Passchendaele battles. The last part of the war was known as "Canada's Hundred Days". By the end of the war, 67,000 Canadians had died and 173,000 were wounded. This was out of 620,000 people who joined the army.

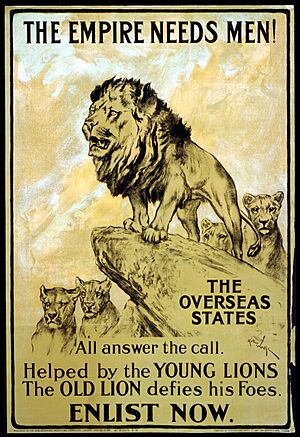

Most Canadians of British background strongly supported the war. They felt it was their duty to fight for their Motherland, Britain. Even Sir Wilfrid Laurier, a French-Canadian leader, said that all Canadians were united behind Britain. However, he later opposed forcing people to join the army. Canadian Prime Minister Robert Borden quickly offered help to Britain, which was accepted.

Contents

Beginning of the War

Getting Ready

Before the war, Canada's army was called the Canadian Militia. It had a small regular army and a larger part-time force. Prime Minister Sir Robert Borden told Sam Hughes, the Minister of Militia and Defence, to train and recruit an army for fighting overseas. At that time, Canada had only 3,110 regular soldiers and a very small navy.

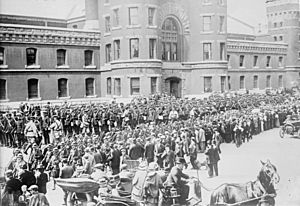

Instead of using the existing militia, a completely new army was formed. This was the Canadian Expeditionary Force. It was made up of numbered battalions and reported to a separate ministry. This new force was put together quickly.

Who Joined the War?

About 600,000 Canadian men and women joined the war effort. They served as nurses, soldiers, and chaplains. At first, non-white people and those born in enemy countries were not easily allowed into the military. For example, when Black people from Sydney, Nova Scotia volunteered, they were told this was a "white man's war."

However, some separate units were formed. In 1915, Indigenous people were allowed to join. About 3,500 Indigenous people served in the Canadian Forces. The Canadian Japanese Association in British Columbia offered 227 volunteers. Some of these men were later accepted into the military. The No. 2 Construction Battalion included Black soldiers from Canada and the United States. These over one thousand Black Canadians remained in separate units during their service.

Thousands of Chinese men also joined the Chinese Labour Corps (CLC). They were mostly poor men from Northern China. They were told they would have non-fighting roles. The Canadian government had rules against Asian immigration. So, the CLC members were secretly brought to Canada. They were trained and then secretly shipped across Canada in cattle-trucks.

Canadian Army Groups

The Canadian Corps

The Canadian Corps was a major fighting group of the Canadian Expeditionary Force. It was formed in September 1915 in France. Most of its soldiers were volunteers. Forcing people to join the army (conscription) did not happen until later in the war. The Corps grew to include four divisions by August 1916. A fifth division was started but later broken up to reinforce the others.

Even though the Corps was part of the British Army, Canadian leaders wanted it to fight as one unit. They did not want its divisions spread out among other armies.

The Corps was first led by Sir Edwin Alderson. Then, Sir Julian Byng took command in 1916. When Byng was promoted in 1917, General Sir Arthur Currie became the commander. He was the first Canadian to lead the Corps. By the end of the war, the Canadian Corps was known as one of the most effective fighting groups on the Western Front.

Canadian Cavalry Brigade

The Canadian Cavalry Brigade arrived in France in 1915. It was made up of Canadian and British regiments. By 1916, it became an all-Canadian group. This brigade fought separately from the Canadian Corps. It was involved in several battles, including the Battle of Moreuil Wood in April 1918.

Fighting on the Western Front

1915 Battles

Neuve Chapelle

The Canadian Expeditionary Force fought its first battle in March 1915. This was in the French town of Neuve Chapelle. Canadian forces were ordered to stop the Germans from sending more troops to this area. This would help the British army push through German lines.

The British did not fully use their advantage because of poor communication. But Canadians learned important lessons. They learned that artillery attacks needed to be stronger. They also learned that communication with troops was too slow and easily broken.

Second Battle of Ypres

In April 1915, the 1st Canadian Division moved to a part of the front line where the British and Allied forces pushed into the German line. On April 22, the Germans tried to remove this bulge by using poison gas. They released 160 tons of chlorine gas from cylinders. This was the first time chlorine gas was used in the war.

When the thick, yellow-green gas clouds drifted over the French lines, their defenses broke. Troops were overcome by the gas and fled, leaving a four-mile gap. The Canadians were the only division that managed to hold their position.

All through the night, Canadians fought to close this gap. On April 24, the Germans launched another gas attack, this time at the Canadian line. In just 48 hours, the Canadians suffered over 6,000 casualties. One out of every three men was hurt or killed, with more than 2,000 deaths.

1916 Battles

Battle of the Somme

Canadians next fought at the Battle of the Somme in the latter half of 1916. This battle was meant to take pressure off French forces fighting at Verdun. However, the Allied forces suffered even more casualties than at Verdun.

The battle started on July 1, 1916. Among the first troops were men from the Royal Newfoundland Regiment. At that time, Newfoundland was a separate country, not part of Canada. So, the Newfoundlanders fought as part of a British division. Their attack went very badly. Out of 801 men, only 68 were present the next day. Every officer who went into battle was killed.

The Canadian Corps joined the battle in September. Their task was to capture the small town of Courcelette, France. The main attack began on September 15. The Canadian Corps attacked a wide area west of Courcelette. By November 11, the 4th Canadian Division had secured most of the German trenches in Courcelette.

The Battle of the Somme resulted in more than 24,000 Canadian casualties. But it also gave Canadian units a strong reputation. British Prime Minister Lloyd George wrote that Canadians were seen as "shock troops" and were used to lead attacks in many battles.

1917 Battles

Battle of Vimy Ridge

For the first time, all four Canadian divisions fought together as one Corps. They were joined by a British division and supported by many artillery, engineer, and labor units. The attack began at 5:43 a.m. on Easter Monday, April 9, 1917. All the Canadian Corps' artillery started firing at once.

The 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Canadian Divisions quickly captured their first objective by 6:25 a.m. The 4th Canadian Division had more trouble but eventually reached its goal. After a planned break, the advance continued. By 7:00 a.m., the 1st Canadian Division had taken half of its second objective. The 2nd and 3rd Divisions also reached their goals around the same time. However, the 3rd Division had to stop and defend its side because the 4th Division had not yet captured the top of the ridge.

By 11:00 a.m., the British 79th Reserve Division counterattacked. But by then, only the 4th Canadian Division had not reached its objective. Fresh brigades were brought up to continue the attack. By 11:00 a.m., the town of Thélus and Hill 135 were captured. The advance paused again to allow troops to get ready. By 2:00 p.m., most of the ridge was secure. Only the northern part of Hill 145 and "the Pimple" (a strong point) were still held by Germans. Fresh troops finally took Hill 145 around 3:15 p.m. "The Pimple" was captured on April 12, ending the battle. By nightfall on April 12, 1917, the Canadian Corps fully controlled the ridge.

The Corps suffered 10,602 casualties: 3,598 killed and 7,004 wounded. The Germans lost about 4,000 men as prisoners. Four Victoria Crosses, the highest military award for bravery, were given to Canadians. The Germans never tried to recapture the ridge.

Battle of Passchendaele

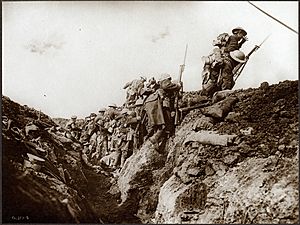

The four divisions of the Canadian Corps were moved to the Ypres Salient to make more advances on Passchendaele. The Canadian Corps took over positions on October 18. This was almost the same area the 1st Canadian Division had held in April 1915. The Canadian plan was to attack in three stages, with breaks in between.

The first stage began on October 26. The 3rd Canadian Division attacked the Bellevue spur. The 4th Canadian Division attacked the Decline Copse. The 3rd Division captured its objectives but had to defend its side. The 4th Division captured its objectives but later retreated due to German counterattacks and communication issues.

The second stage began on October 30. It aimed to capture areas missed in the first stage and prepare for the final attack. The southern part quickly captured Crest Farm. The northern part faced strong German resistance. The 3rd Canadian Division captured several farms and crossroads but did not fully reach its goal.

There was a seven-day break before the third stage. Three days without rain helped with supplies and troop reorganization. The third stage began on November 6. The 1st and 2nd Canadian Divisions took over the front lines. Less than three hours after the attack started, many units reached their goals. The town of Passchendaele was captured.

A final action to take the remaining high ground north of the village happened on November 11. This ended the long Third Battle of Ypres. The Second Battle of Passchendaele cost the Canadian Corps 15,654 casualties, with over 4,000 dead, in 16 days of fighting.

1918 Battles

Hundred Days Offensive

Throughout the last three months of the war, Canadian troops fought in several areas. The first was near Amiens on August 8. The Canadian Corps, along with New Zealand, Australian, French, and British forces, led the attack on German forces. This battle greatly hurt the morale of the German army. German General Ludendorff called it a "black day for the German army." After their success at Amiens, Canadians were moved to Arras to break through the strong Hindenburg Line.

Between August 26 and September 2, the Canadian Corps launched many attacks near the Canal du Nord. On September 27, 1918, the Canadian Corps broke through the Hindenburg Line by crossing a dry section of the Canal du Nord. The operation ended successfully on October 11, 1918. Canadian forces drove the Germans out of their main supply center in the Battle of Cambrai. The Corps continued with quick successes at Denain and Valenciennes. On the final day of the war, they marched successfully into Mons.

This period was very successful but also very costly. The Canadian Corps suffered 46,000 casualties in the last hundred days of the war. The last Canadian soldier killed was Private George Lawrence Price. He died two minutes before the war officially ended at 11 a.m. on November 11. He is often recognized as the last British soldier killed in World War I.

Atlantic Campaign

When World War I began on August 5, 1914, two government ships, CGS Canada (renamed HMCS Canada) and CGS Margaret, were immediately used by the navy. They joined HMCS Niobe, HMCS Rainbow, and two submarines, HMCS CC-1 and HMCS CC-2. These ships formed the start of Canada's naval force. Many Canadian men chose to join the larger British Royal Navy instead of the smaller Canadian navy.

In late 1914, HMCS Rainbow patrolled the west coast of North America. These patrols became less important after the German naval threat in the Pacific ended in December 1914. By 1917, Rainbow was taken out of service.

HMCS Niobe also patrolled off the coast of New York City to help with the British blockade. But she returned to Halifax in July 1915 and was no longer fit for active service. She was badly damaged in the December 1917 Halifax Explosion.

The submarines CC-1 and CC-2 patrolled the Pacific for three years. In 1917, they were moved to Halifax. They were the first warships to travel through the Panama Canal flying the Canadian navy's flag. But they were declared unfit for service and never patrolled again.

In June 1918, a German U-boat deliberately sank the Canadian hospital ship HMHS Llandovery Castle. The U-boat then machine-gunned survivors in the water. This was the most significant Canadian naval disaster of the First World War in terms of lives lost.

In September 1918, the Royal Canadian Naval Air Service (RCNAS) was formed. Its main job was to find and fight submarines using patrol aircraft. However, after the war ended on November 11, 1918, the RCNAS was stopped.

Home Front

Conscription

A big disagreement grew between French and British Canadians during World War I. Many French Canadians did not feel they had to serve British interests. This issue became very serious when Canadian Prime Minister Robert Borden introduced the Canadian Military Service Act of 1917. This law made joining the army compulsory.

While some farmers and factory workers opposed the law, the strongest protests came from Quebec. Quebec nationalist Henri Bourassa and Sir Wilfrid Laurier led the campaign against conscription. They argued that the war was dividing Canadians. In the 1917 election, Robert Borden convinced enough English-speaking Liberals to vote for his party. His Union government won 153 seats, mostly from English Canada. The Liberals won 82 seats. The Union government won only 3 seats in Quebec.

Out of 120,000 conscripted soldiers, only 47,000 were sent overseas. Despite this, the split between French and English-speaking Canadians lasted for many years.

Women's Role

During World War I, Canadian women helped in many ways. They worked in factories, raised money, and served as nurses overseas. These women had a big impact on the war effort. Others volunteered to knit socks, roll bandages, and pack food for the troops. Women put on shows to raise money for supplies needed overseas.

The shortage of men meant women had to work outside the home. They often took jobs that men usually did. They worked in banks, insurance companies, and as gas station attendants, streetcar conductors, and fish cannery workers. Even though they did the same jobs as men, they were paid less. When Prime Minister Robert Borden ordered compulsory military service in May 1917, many women were called to run farms, build aircraft and ships, and work in munitions factories. By the end of the war, women had earned the right to vote. They were also gaining more independence in society.

Influence on Canada

National Identity

Historians discuss how World War I affected Canada's identity. Most English-speaking Canadians in the early 1900s felt they were both British subjects and Canadians. Being part of the British Empire was a key part of being Canadian. Many defined Canada as the part of North America loyal to the British Crown.

Some historians say that Canadian nationalism was strongest in French Canada. They point to Henri Bourassa, who left Wilfrid Laurier’s government to protest sending Canadian troops to the South African War. This is seen as a clash between loyalty to the Empire and Canadian nationalism.

Other historians suggest Canada was already becoming more independent from Britain before 1914. Canada's government created a Department of External Affairs (like a foreign ministry) in 1909. This department worked closely with British diplomats. However, Canadian officials had already negotiated treaties with other countries in the 1880s with little British involvement. This shows Canada's slow move towards independence was already happening. World War I may have sped up this process.

While most English-speaking Canadians had a mixed British-Canadian identity before the war, the war's effect on Canada's nationhood is debated. Canadian media often call World War I, especially the Battle of Vimy Ridge, "the birth of a nation." Some historians see the First World War as Canada's "war of independence." They argue it reduced how much Canadians identified with the British Empire. It made them feel more Canadian first. They believe pride in Canada's battlefield achievements boosted Canadian patriotism. Also, the huge losses on the Western Front made some Canadians feel less connected to Britain.

Other historians disagree. They argue that the war did not destroy the mixed British-Canadian identity. They say most English-speaking Canadians continued to believe Canada should be a "British" nation. They also point out that many Canadian soldiers were British immigrants. About half of the soldiers at Vimy Ridge were British immigrants. Their victory also involved close work with British units.

Some historians note that Canada's British identity did not disappear until the 1950s and 1960s. This was when Canada adopted its current flag and started disagreeing with Britain on foreign policy, like during the 1956 Suez Crisis.

Art and Literature

- "In Flanders Fields" by Canadian soldier John McCrae is one of the most famous poems. Written after the Second Battle of Ypres, it and the remembrance poppy it inspired are symbols of Remembrance Day across the Commonwealth.

- Rilla of Ingleside (1921) is a book by Lucy Maud Montgomery. It uses the war as its background. The book tells the story of Anne and her family in Canada during the war. They wait for Anne's three sons to return from fighting overseas. This book is the only novel from that time that shows the war from the perspective of Canadian women.

See also

- Canadian pipers in World War I

- Canadian war memorials

- List of Canadian battles during World War I

- List of Canadian soldiers executed during World War I

- List of Canadian Victoria Cross recipients

- History of the Royal Canadian Navy

- History of Canadian foreign relations

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |