Canadian National Vimy Memorial facts for kids

The Canadian National Vimy Memorial is a special place in France that remembers Canadian soldiers who died during the First World War. It also honors those soldiers who were killed or went missing in France and whose graves are unknown. This monument is the main part of a large park, about 100 hectares (the size of 250 football fields), which was once a battlefield. Here, the Canadian army fought bravely during the Battle of Vimy Ridge.

The Battle of Vimy Ridge was very important because it was the first time all four Canadian army divisions fought together as one team. This battle became a symbol of Canada's achievements and sacrifices. France gave Canada this land forever, so Canada could create a park and memorial. Even today, you can still see old tunnels, trenches, and craters from the war. Some areas are closed off because there might still be unexploded bombs, making it unsafe. The park also has other memorials and cemeteries.

It took the designer, Walter Seymour Allward, eleven years to build this amazing monument. King Edward VIII officially opened it on July 26, 1936. More than 50,000 people, including 6,200 Canadians, came to the ceremony. After a big restoration project, Queen Elizabeth II rededicated the monument on April 9, 2007, to mark 90 years since the battle. Veterans Affairs Canada takes care of the site. The Vimy Memorial is one of only two National Historic Sites of Canada located outside of Canada.

Quick facts for kids Canadian National Vimy MemorialMémorial national du Canada à Vimy |

|

|---|---|

| Veterans Affairs Canada Commonwealth War Graves Commission |

|

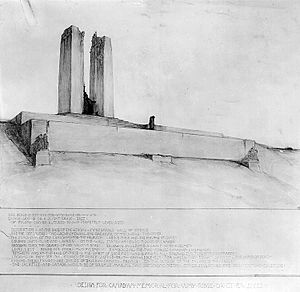

Walter Allward's memorial design submission

|

|

| For First World War Canadian dead and missing, presumed dead, in France | |

| Unveiled | 26 July 1936 By King Edward VIII |

| Location | 50°22′46″N 2°46′25″E / 50.379444°N 2.773611°E near |

| Designed by | Walter Seymour Allward |

| Commemorated | 11,169 |

|

English: To the valour of their countrymen in the Great War and in memory of their sixty thousand dead this monument is raised by the people of Canada.

French: À la vaillance de ses fils pendant la Grande Guerre et en mémoire de ses soixante mille morts, le peuple canadien a élevé ce monument. |

|

| Official name: Vimy Ridge National Historic Site of Canada | |

| Designated: | 1996 |

| Statistics source: Cemetery details. Commonwealth War Graves Commission. | |

Contents

The Story of Vimy Ridge

The Land and Its History

Vimy Ridge is a gently rising hill on the edge of the Douai Plains, about 8 kilometers (5 miles) northeast of Arras. It rises slowly on one side and drops quickly on the other. The ridge is about 7 kilometers (4.3 miles) long and 700 meters (2,300 feet) wide at its narrowest point. It reaches 145 meters (476 feet) above sea level, which is about 60 meters (200 feet) higher than the plains below. This height gave a clear view for many kilometers in all directions.

German forces took control of Vimy Ridge in October 1914. French and British armies tried many times to push the Germans out. In May 1915, the French army briefly captured the highest part of the ridge, where the memorial now stands. But they couldn't hold it because they didn't get enough help. The French tried again in September 1915 but failed. They lost about 150,000 soldiers trying to take Vimy Ridge.

British soldiers took over the area from the French in February 1916. In May 1916, German soldiers attacked the British lines. They captured some tunnels and craters before stopping. The British tried to fight back but couldn't change the situation. In October 1916, the Canadian army took over from the British soldiers on the ridge.

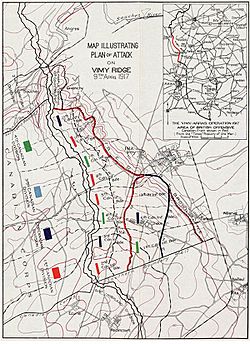

The Battle of Vimy Ridge

The Battle of Vimy Ridge was the first time all four Canadian divisions fought together. The Canadian army needed a lot of support for this big attack. So, British soldiers and extra artillery (big guns), engineers, and workers joined them. German forces had three divisions defending the ridge.

The attack started at 5:30 AM on April 9, 1917. Light field guns fired a moving barrage (a wall of explosions) that moved forward every few minutes. Heavier guns fired at known German defenses further away. The 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Canadian Divisions quickly captured their first targets. The 4th Canadian Division had more trouble and took longer to reach its first goal. This delay meant the 3rd Canadian Division had to create a defensive line to its north. Reserve units from the 4th Canadian Division eventually pushed the German troops off the top of Hill 145.

On April 10, Canadian commander Julian Byng brought in three new brigades. These fresh units moved past the tired ones and captured the third line of targets, including Hill 135 and the town of Thélus, by 11:00 AM. By 2:00 PM, the 1st and 2nd Canadian Divisions had captured their final targets. Only a heavily defended hill called "the Pimple" remained under German control. On April 12, the 10th Canadian Brigade, with help from artillery and British soldiers, attacked and quickly took "the Pimple." By the end of April 12, the Canadian army fully controlled the ridge.

The Canadian army suffered 10,602 casualties (soldiers killed or wounded) in the battle: 3,598 killed and 7,004 wounded. The German army also had many casualties, and about 4,000 of their soldiers were taken prisoner.

Even though it's not always called Canada's greatest military victory, the Battle of Vimy Ridge became very important for Canada's national identity. Many people believe that Canada's sense of nationhood was born out of this battle.

Building the Memorial

Choosing the Design

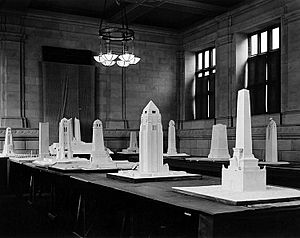

In 1920, the Canadian government decided to build memorials at eight important battle sites in France and Belgium. They first thought about building the same monument at each site. But then they held a competition for architects, designers, sculptors, and artists from Canada.

Out of 160 designs, the jury chose 17 finalists. In October 1921, they picked the design by Walter Seymour Allward, a sculptor from Toronto. Allward's design was very complex, so it couldn't be copied at every site. The commission then decided to build two unique memorials (Allward's and another by Frederick Chapman Clemesha) and six smaller, identical ones.

At first, there was a debate about where to build Allward's main memorial. Some thought it would look best on a lower hill. But Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King wanted it at Vimy Ridge. The Canadian Parliament agreed with him. So, Vimy Ridge was chosen.

In 1922, France officially gave Canada 100 hectares (250 acres) of land on Vimy Ridge, including Hill 145. This was a gift to thank Canada for its efforts in the war. The only condition was that Canada use the land for a monument to its fallen soldiers and take care of the memorial and the battlefield park.

Construction of the Memorial

Allward moved to Europe in 1922 to work on the project. He wanted to use white marble for the memorial, but others advised against it because it might not last well in northern France. Allward spent almost two years searching for the right stone. He found it in Croatia, a durable limestone called Seget limestone.

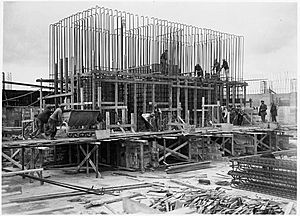

Getting the stone was difficult, which delayed the construction. The first shipment arrived in 1927, and the larger blocks for the human figures didn't arrive until 1931. Construction officially began in 1925 and took eleven years to finish. French and British veterans helped build roads and landscape the site.

Allward used a new method for the monument: limestone blocks attached to a concrete frame. The memorial sits on a huge concrete foundation, weighing 11,000 tonnes and reinforced with steel. The base and the two tall towers (pylons) contain almost 6,000 tonnes of limestone.

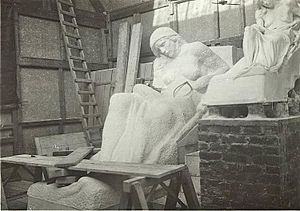

Sculptors carved the 20 large human figures directly on site from big stone blocks. They used smaller plaster models made by Allward and a special tool called a pantograph to make the figures the correct size. The carvers worked all year long inside temporary shelters built around each figure.

At first, the names of the missing soldiers were not part of Allward's design. He wanted to put them on pavement stones around the monument. But the commission insisted that the names of the 11,285 Canadians killed in France with no known grave be carved directly onto the memorial walls. Allward designed a special typeface for these names.

The 1936 Unveiling Ceremony

After the war, many people wanted to visit the battlefields. In 1934, the Canadian Legion announced a special trip for veterans and their families to visit the battlefields and attend the Vimy Memorial's unveiling. This was the largest peacetime movement of people from Canada to Europe at the time. About 6,200 Canadians traveled on five ships, escorted by two Canadian navy ships.

On July 26, 1936, the day of the ceremony, people explored the memorial park. Sailors from the Canadian navy provided a guard of honor. Bands, French army engineers, and French-Moroccan cavalry were also present. The ceremony was broadcast live by radio to Canada. Over 50,000 people attended, including King Edward VIII and French President Albert Lebrun.

King Edward VIII, as King of Canada, inspected the guard of honor and spoke with veterans. Two British and two French air force squadrons flew over the monument. The ceremony included prayers and speeches. King Edward VIII spoke in both French and English, thanking France and promising that Canada would never forget its fallen soldiers. He then pulled the flag from the central figure of "Canada Bereft," and the military band played "The Last Post." This was one of the King's last official duties before he gave up his throne.

Second World War and Beyond

When the Second World War started in 1939, Canada worried about the memorial's safety. They protected the sculptures with sandbags. In May 1940, German forces took control of the area. There were rumors that the memorial had been destroyed. However, the German government denied this. To prove it, Adolf Hitler himself was photographed touring the memorial in June 1940. The memorial was found undamaged in September 1944 when British troops recaptured Vimy Ridge.

After the Second World War, people didn't pay much attention to the Vimy Memorial for a while. Interest grew again in 1967 for the 50th anniversary of the battle and Canada's 100th birthday. A large ceremony was held and broadcast live on TV. Interest faded again but returned strongly in 1992 for the 75th anniversary, with Canadian Prime Minister Brian Mulroney and 5,000 people attending.

Restoration and Rededication

By the end of the 20th century, the memorial needed major repairs. Water was getting into the stone and concrete, causing damage and making the carved names hard to read. In 2001, the Canadian government announced a $30 million project to restore its memorials in France and Belgium.

The Vimy Memorial closed for major restoration in 2005. Workers removed old repairs, replaced damaged stones with new ones from the original quarry in Croatia, and fixed problems with the structure and drainage.

Queen Elizabeth II, with Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, rededicated the restored memorial on April 9, 2007. This ceremony marked the 90th anniversary of the battle. Thousands of Canadian students, veterans, and descendants of those who fought at Vimy attended. It was the largest crowd at the site since the 1936 dedication.

100th Anniversary

The 100th anniversary of the Battle of Vimy Ridge was held at the memorial on April 9, 2017. This was also during Canada's 150th birthday celebrations. About 30,000 people were expected to attend.

Important guests from Canada included Governor General David Johnston, Prince Charles, Prince William, Prince Harry, and Prime Minister Justin Trudeau. French President François Hollande and Prime Minister Bernard Cazeneuve also attended. Queen Elizabeth II sent a message, saying Canadians "fought courageously and with great ingenuity."

To mark the anniversary, Canada Post and France's La Poste released two special postage stamps featuring the memorial.

The Memorial Site

The Canadian National Vimy Memorial site is about 8 kilometers (5 miles) north of Arras, France. It is surrounded by small towns like Vimy and Givenchy-en-Gohelle. This site is one of the few places on the old Western Front where you can still see First World War trenches and the battlefield as they were.

The entire site is 100 hectares (250 acres). Much of it is forested and closed to visitors because of safety concerns, like unexploded bombs. Sheep graze in the open areas to keep the grass short, as it's too dangerous for people to cut it.

Besides the main Vimy Memorial, the site also has other memorials. These include memorials to the French Moroccan Division, the Lions Club International, and Lieutenant-Colonel Mike Watkins. There are also two war cemeteries here. The site is popular for tours and is important for studying battlefield history. The visitors' center helps people understand the memorial, the battlefield, and Canada's role in the First World War.

The Vimy Memorial Itself

Allward built the memorial on Hill 145, the highest point on the ridge. The memorial has 20 human figures that help tell its story. The front wall is 7.3 meters (24 feet) high and looks like a strong defense.

At each end of the front wall, there are groups of figures. "The Breaking of the Sword" is at the south end, showing three young men, one breaking his sword. This represents the end of war and the hope for peace. "Sympathy of the Canadians for the Helpless" is at the north end, showing one man standing while others are suffering. This represents Canada's care for the weak. Above each group, there are carved cannon barrels with laurel and olive branches, symbolizing victory and peace.

A cloaked young woman stands at the center of the front wall, looking over the plains. Her head is bowed, showing sadness. Below her is a stone coffin with a helmet and sword. This sad figure, called "Canada Bereft" or "Mother Canada," represents Canada mourning its dead. This statue is the largest single piece in the monument and was carved from one 30-tonne block of stone. The area in front of the memorial is a grassy space, while the battle-damaged land around the sides and back was left untouched.

Two tall towers, called pylons, rise 30 meters (98 feet) above the memorial's platform. One pylon has a maple leaf for Canada, and the other has a fleur-de-lis for France. They symbolize the unity and sacrifice of both countries. At the top of the pylons are figures called the "Chorus." The main figures are "Justice" and "Peace." "Peace" holds a torch high, making it the highest point in the area. Other figures below them represent "Faith," "Hope," "Truth," "Honour," "Charity," and "Knowledge." Shields of Canada, Britain, and France are around these figures. Large crosses are on the outside of each pylon.

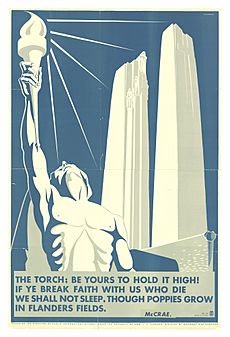

At the base of the pylons, there are inscriptions honoring Canada's war dead in both French and English. Between the two pylons is the "Spirit of Sacrifice." Here, a dying young soldier looks up in a pose like a crucifixion. He has passed his torch to a comrade who holds it high behind him. This refers to the poem "In Flanders Fields" and means keeping the memory of the war dead alive.

On the back side of the monument, on either side of the western steps, are the "Mourning Parents." These figures, one male and one female, represent the grieving mothers and fathers of the nation.

Carved on the outside walls of the monument are the names of the 11,285 Canadians killed in France whose graves are unknown. Allward wanted the names to be a continuous list, so they are carved across both vertical and horizontal stone seams. This means that if a soldier's remains were later found, their name could not be removed from the memorial without breaking the flow of names.

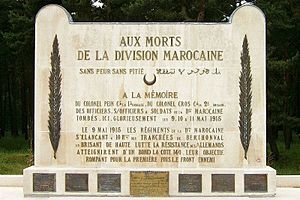

Moroccan Division Memorial

The Moroccan Division Memorial remembers the French and Foreign soldiers of the Moroccan Division who died during the Second Battle of Artois in May 1915. Veterans of the division built this monument, which was opened on June 14, 1925.

The Moroccan Division was made up of soldiers from different places, including Tunisia, Algeria, and the French Foreign Legion. The Legionnaires came from 52 different countries, including Americans, Poles, Russians, and Italians.

In the battle on May 9, 1915, the Moroccan Division quickly moved through German defenses, advancing 4 kilometers (2.5 miles) in two hours. They captured the highest part of the ridge but had to retreat because they didn't get enough support. Even so, they held onto 2,100 meters (2,300 yards) of land. The division suffered many casualties, including both of its brigade commanders.

Grange Subway

The Western Front during the First World War had many tunnels and dugouts. The Grange Subway is a tunnel system about 800 meters (875 yards) long. It used to connect the reserve lines to the front lines, allowing soldiers to move quickly and safely underground. A part of this tunnel system is open to the public, with tours led by Canadian student guides.

The area around Vimy was good for digging tunnels because the ground was soft chalk but very stable. So, underground warfare was common here since 1915. Before the Battle of Vimy Ridge, British tunneling companies dug 12 subways for the Canadian army. These tunnels were about 10 meters (33 feet) deep to protect against large artillery shells. They were often dug at a speed of 4 meters (13 feet) a day and were usually 2 meters (6.6 feet) tall and 1 meter (3.3 feet) wide. This underground network sometimes included hidden rail lines, hospitals, command posts, and ammunition stores.

Lieutenant-Colonel Mike Watkins Memorial

Near the Canadian trenches, there is a small memorial plaque for Lieutenant-Colonel Mike Watkins. He was a British expert in dealing with bombs. In August 1998, he died when a tunnel roof collapsed while he was exploring the British tunnel system at the Vimy Memorial site. Earlier that year, he had successfully disarmed 3 tonnes of old explosives under a road on the site.

Visitors' Centre

The site has a visitors' center, where Canadian student guides work. It is open every day. During the memorial's restoration, the old visitors' center was replaced by a temporary one, which is still used today. The visitors' center is now near the preserved trenches and craters from the war, and close to the entrance of the Grange Subway. A new educational visitors' center was completed by April 2017, for the 100th anniversary of the battle.

Why Vimy Ridge is Important

The Canadian National Vimy Memorial site is very important for Canada's culture and history. Many people believe that Canada's national identity and nationhood were formed during the Battle of Vimy Ridge. Some historians suggest that building the Vimy memorial showed Canada's growing pride as a nation between the two World Wars. The memorial has become a lasting symbol of the entire First World War and the huge impact of war in general. The restoration project in 2005 showed that a new generation is determined to remember Canada's contributions and sacrifices.

The Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada recognized the site's importance by making it a National Historic Sites of Canada in 1996. It is one of only two such sites outside of Canada. The other is the Beaumont-Hamel Newfoundland Memorial, also in France.

The Vimy Foundation was created to preserve and promote Canada's First World War legacy. Vimy Ridge Day is also celebrated to remember the soldiers who died or were wounded in the battle. A local Vimy resident, Georges Devloo, spent 13 years giving free car rides to Canadian tourists to and from the memorial as a way to honor the Canadians who fought there.

Some people have different opinions about the memorial. They argue that the monument's different parts send mixed messages. For example, the triumphant figures at the top of the pylons seem to conflict with the sad figures at the base. Also, the text celebrating victory seems different from the list of names of the missing.

The memorial often inspires art. In 1931, Will Longstaff painted "Ghosts of Vimy Ridge," showing ghosts of Canadian soldiers around the memorial, even though it wasn't finished yet. The memorial has been featured on stamps in France and Canada. The Canadian "Tomb of the Unknown Soldier" was chosen from a cemetery near the Vimy Memorial, and its design is based on the stone coffin at the base of the Vimy memorial.

The Royal Canadian Mint has released special coins featuring the memorial. The Sacrifice Medal, a Canadian military award created in 2008, has an image of "Mother Canada" on its back. A sculpted image of the memorial is in the French Embassy in Canada, showing the close relationship between the two countries. The Vimy Memorial is also shown on the back of the Canadian $20 banknote.

See also

In Spanish: Monumento conmemorativo nacional canadiense de Vimy para niños

In Spanish: Monumento conmemorativo nacional canadiense de Vimy para niños

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |