Commonwealth War Graves Commission facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Commonwealth War Graves Commission

|

|

|---|---|

| Headquarters | Maidenhead, United Kingdom |

| Official languages | English |

| Type | Intergovernmental organization and commission |

| Membership | |

| Leaders | |

|

• Patron

|

The King |

|

• President

|

The Princess Royal |

|

• Director-General

|

Claire Horton |

| Establishment | |

|

• Founded as the Imperial War Graves Commission

|

21 May 1917 |

|

• Name changed to Commonwealth War Graves Commission

|

28 March 1960 |

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) is an international group of six countries. Their main job is to find, record, and look after the graves and memorials of military members from the Commonwealth of Nations who died in the two World Wars. They also remember civilians who died because of enemy attacks during World War II.

Sir Fabian Ware started the commission. It was officially created by Royal Charter in 1917 as the Imperial War Graves Commission. Its name changed to the Commonwealth War Graves Commission in 1960.

The CWGC makes sure that all Commonwealth war dead are remembered equally. This means each person gets their name on a headstone at their burial site or on a memorial. Everyone is remembered the same way, no matter their military rank, background, or beliefs.

Today, the CWGC looks after 1.7 million Commonwealth military members who died. They are in 153 countries around the world. Since it began, the commission has built about 2,500 war cemeteries and many memorials. They now care for graves at over 23,000 different sites. They also maintain more than 200 memorials worldwide.

Besides Commonwealth military members, the CWGC also looks after over 40,000 non-Commonwealth war graves. They also care for over 25,000 other military and civilian graves. The commission gets money from its member countries: the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, India, and South Africa. The current Patron of the CWGC is King Charles III. The President is Anne, Princess Royal.

Contents

How the CWGC Began and Grew

Remembering Soldiers from World War I

When World War I started in 1914, Fabian Ware was 45 years old. He was too old to join the British Army. So, he became a leader of a British Red Cross unit in France. He noticed that no one was officially keeping track of where soldiers were buried.

In March 1915, Ware's work became official. His group joined the British Army as the Graves Registration Commission. By October 1915, they had recorded over 31,000 graves. By May 1916, this number grew to 50,000.

As cemeteries filled up, Ware started to get land for new ones. He made agreements with France and Belgium. These agreements said that the land would be given forever. This allowed the British to manage and care for the cemeteries.

Families of fallen soldiers began asking for information and photos of graves. By 1917, 17,000 photos had been sent out. The Graves Registration Commission then became the Directorate of Graves Registration and Enquiries. This new name showed that their work was growing. They were now helping families and working in other war zones like Greece and Egypt.

The Official Start of the Commission

As the war continued, people worried about what would happen to the graves after the fighting stopped. In January 1916, the government formed the National Committee for the Care of Soldiers' Graves. Edward, Prince of Wales, became its president.

By early 1917, it was clear that a special organization was needed to care for the graves across the British Empire. On May 21, 1917, the Imperial War Graves Commission was officially created by Royal Charter. The Prince of Wales was its president. Fabian Ware was the vice-chairman.

After World War I ended, the commission began its huge task. They had to record details of all the dead. By 1918, they had found 587,000 graves. Another 559,000 soldiers had no known grave.

The war had so many deaths that people started to think differently about remembering soldiers. Before, only high-ranking officers were often remembered individually. But now, everyone expected to be honored. A committee led by Frederic Kenyon suggested two main ideas:

- Bodies should not be brought home.

- All memorials should look the same, no matter a soldier's rank.

In 1919, Rudyard Kipling wrote an article in The Times. It explained the commission's plans for the graves. This article was then published as a booklet called Graves of the Fallen. It showed pictures of beautiful cemeteries with trees and shrubs.

However, some people were upset. They wanted bodies to be brought home. There was a big debate in Parliament in 1920. But in the end, the commission's plans were approved.

First Cemeteries and Memorials

In 1918, three famous architects were chosen: Sir Herbert Baker, Sir Reginald Blomfield, and Sir Edwin Lutyens. Rudyard Kipling helped with the words for the memorials.

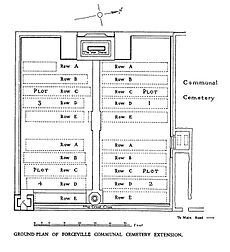

In 1920, the commission built three test cemeteries. The one at Forceville was the most successful. It had uniform headstones in a garden setting. It also featured Blomfield's Cross of Sacrifice and Lutyens' Stone of Remembrance. Forceville became the model for all future cemeteries.

By 1921, the commission had set up 1,000 cemeteries. Between 1920 and 1923, they sent 4,000 headstones to France every week. By 1927, over 500 cemeteries were built. They had 400,000 headstones, a thousand Crosses of Sacrifice, and 400 Stones of Remembrance.

The commission also had to remember soldiers who had no known grave. There were 315,000 of them in France and Belgium alone. They decided to build large memorials for these missing soldiers.

The Menin Gate in Belgium was the first memorial to the missing to be finished in Europe. It was opened in 1927. Other memorials followed, like the Thiepval Memorial on the Somme. Countries like Canada and Australia also built their own memorials for their missing soldiers. By 1932, most of the work for World War I dead was complete.

Remembering Soldiers from World War II

When World War II started in 1939, the commission quickly set up grave registration units. They also planned for new cemeteries. After the war, they began restoring World War I cemeteries. They also started remembering the 600,000 Commonwealth soldiers who died in World War II. Like before, bodies were not brought home, and memorials were uniform.

In 1949, the commission finished the Dieppe Canadian War Cemetery. This was the first of 559 new cemeteries and 36 new memorials. They put up over 350,000 new headstones. Because World War II was so widespread, building and restoring took much longer.

The number of civilians who died in World War II was much higher. So, Winston Churchill agreed that the commission should also record civilian war deaths. A new part was added to the commission's charter in 1941. This allowed them to record the names of civilians who died from enemy action. This led to the Civilian War Dead Roll of Honour. It eventually had nearly 67,000 names. This roll is now kept in Westminster Abbey.

After World War II

After World War II, the commission changed its name in 1960. They removed 'Imperial' and became the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. This showed that the organization was now more about the Commonwealth countries working together.

Sometimes, conflicts make it hard for the commission to care for cemeteries. For example, during the Lebanese Civil War, two cemeteries in Beirut were destroyed and had to be rebuilt. Caring for graves in Iraq has also been difficult since the 1980s.

The commission also helps with other war graves. In 1982, they helped design cemeteries in the Falkland Islands for those who died in the Falklands War. They also manage graves from the Second Boer War. Since 2003, they have helped Veterans Affairs Canada find grave markers for Canadian veterans.

In 2008, a mass grave was found near Fromelles. Two hundred and fifty British and Australian bodies were found. They were buried in the new Fromelles (Pheasant Wood) Military Cemetery. This was the first new CWGC cemetery in over 50 years.

Cemeteries and Memorials Around the World

The CWGC looks after 1.7 million Commonwealth military members who died in 153 countries. They also remember about 67,000 civilians who died in World War II. Each military member is remembered by name on a headstone or a memorial. The commission cares for graves at over 23,000 sites. They also maintain more than 200 memorials worldwide. Most burial sites are in existing cemeteries. However, the commission has built about 2,500 war cemeteries. The largest memorial for the missing is the Thiepval Memorial.

Who is Remembered?

The commission only remembers those who died during specific war years. This includes military members who died in service or from causes related to their service. This means deaths from combat, training accidents, air raids, or diseases like the 1918 flu.

- For World War I, the period is August 4, 1914, to August 31, 1921.

- For World War II, it's September 3, 1939, to December 31, 1947.

Civilians who died from enemy action in World War II are remembered differently. Their names are on the Civilian War Dead Roll of Honour in Westminster Abbey. The commission also looks after over 40,000 non-Commonwealth war graves. They also care for over 25,000 other military and civilian graves.

Architects and Artists Who Designed the Sites

Famous architects like Sir Herbert Baker, Sir Reginald Blomfield, and Sir Edwin Lutyens designed many of the cemeteries and memorials. They were the main architects for France and Belgium. Other architects worked in different regions.

Many younger architects also helped design the cemeteries and memorials. Some of them had even served in the war. Leading sculptors like Eric Henri Kennington and Charles Sargeant Jagger created the art for the memorials. After World War II, Edward Maufe became the main architect for the UK.

How Cemeteries Are Designed

The CWGC cemeteries have a special look that makes them easy to recognize. They usually have a low wall or hedge around them and a metal gate. In France and Belgium, a tablet near the entrance says the land was given by those governments.

Most cemeteries have a book with a list of burials, a map, and the cemetery's history. This book is kept in a metal box. The headstones are all the same size and design.

The cemetery grounds are usually covered in grass with flowers around the headstones. There is no paving between the rows of graves. This makes the cemetery feel like a peaceful garden.

Cross of Sacrifice and Stone of Remembrance

Cemeteries with more than 40 graves usually have a Cross of Sacrifice. This cross was designed by Reginald Blomfield. It looks like old medieval crosses. It's a stone cross with a bronze sword pointing down. The cross represents faith, and the sword represents the military.

Cemeteries with over 1,000 burials often have a Stone of Remembrance. This stone was designed by Edwin Lutyens. It has the words "Their name liveth for evermore" carved on it. Rudyard Kipling came up with the idea for this stone. It was designed to remember everyone, no matter their religion. The stone is 12 feet long and 5 feet high.

Headstones

Every grave has a headstone. Each headstone shows the country's emblem or army badge, rank, name, unit, date of death, and age. It also has a religious symbol and a personal message chosen by the family. The letters on the headstones are all in a special style designed by MacDonald Gill. Most headstones are made of Portland stone. They are 30 inches tall, 15 inches wide, and 3 inches thick.

Most headstones have a cross. But if the person was not Christian, they have a different symbol or no symbol. If a soldier used a fake name, their real name is shown with "served as". For unknown soldiers, the headstone says "A Soldier of the Great War known unto God". Sometimes, one headstone covers more than one grave if bodies could not be told apart.

In places with bad weather or earthquakes, like Thailand, different types of markers are used. These are stone pedestals instead of tall headstones. In Italy, headstones are made from local limestone. In Greece, small headstones are laid flat on the ground to prevent earthquake damage.

Garden Design

The CWGC cemeteries are known for their beautiful gardens. The idea was to create a peaceful place for visitors. They used plants that would remind people of gardens back home.

The areas around each headstone are planted with roses and other flowers. Low-growing plants are used in front of headstones so the names can be seen. The grass paths add to the garden feel. In dry places, they use plants that don't need much water. In tropical areas, they use different kinds of plants. Gardeners work in teams in areas with many cemeteries. Larger cemeteries have their own staff.

How the CWGC is Organized

Leaders of the Commission

A group of Commissioners oversees the CWGC. The President is Princess Anne. The Chairman is the United Kingdom's Secretary of State for Defence, Grant Shapps MP. Claire Horton became the Director-General in 2020.

The board also includes High Commissioners from New Zealand, Australia, South Africa, India, and Canada. Other important members also serve on the board.

Where the CWGC Works

The CWGC's main office is in Maidenhead, England. They have offices or teams around the world that manage different areas:

- United Kingdom and Northern Area: Covers the UK, Ireland, and countries like Sweden, Norway, and parts of Russia.

- Central and Southern Europe Area: Looks after Belgium, Germany, the Netherlands, and countries like Italy, Greece, and Poland.

- France Area: Responsible for France, Switzerland, Spain, and Portugal.

- Canada, Americas and Pacific Area: Covers Canada, the United States, many countries in the Americas, and places like Japan, Singapore, and Thailand.

- Africa and Asia Area: Manages sites in Africa, India, the Middle East, and Turkey.

How the CWGC is Funded

The CWGC gets most of its money from the six member countries. In 2020/21, they received about £66.1 million. This means it costs about $85 CAD to remember each war dead person. Each country pays a share based on how many graves the CWGC looks after for them:

- United Kingdom: 79%

- Canada: 10%

- Australia: 6%

- New Zealand: 2%

- South Africa: 2%

- India: 1%

Ongoing Work and Discoveries

Finding and Reburying Soldiers

After World War I, the British Army was in charge of finding bodies. They searched battlefields and reburied over 204,000 bodies by 1921. Even after this, many bodies were still found. In the mid-1920s, 20 to 30 bodies were found every week.

Today, about 30 bodies from World War I and II are still found each year. When a Commonwealth soldier's remains are found, the CWGC is told. A burial officer tries to find anything that can help identify the person. This might include items found with the remains, or DNA.

People can also research old records to identify soldiers. The CWGC's records are open to the public. For example, in 2013, a soldier named Philip Frederick Cormack was found to be buried in a French cemetery. He was previously only on a memorial for the missing. Another soldier, Sergeant Leonard Maidment, was identified after a visitor found an unknown sergeant's headstone and used records to figure out who he was. The "In From The Cold Project" has identified over 7,255 people whose graves were unmarked or names were missing.

Fairness in Commemoration

In April 2021, a special committee of the CWGC released a report. It talked about how black and Asian troops were not always remembered properly after World War I. The CWGC and the committee made public statements about this. The Defence Secretary, Ben Wallace, officially apologized in Parliament. The CWGC is now working to fix these past issues.

See also

- American Battle Monuments Commission

- German War Graves Commission

- World War I memorials

| Toni Morrison |

| Barack Obama |

| Martin Luther King Jr. |

| Ralph Bunche |