Battle of Quebec (1690) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Quebec |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the War of the Grand Alliance, King William's War |

|||||||

The batteries of Quebec bombard the New England fleet |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 2,300 provincial soldiers 60 natives 6 field guns 34 warships |

Marines, 2,000 militia | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| At least 150 killed, large number wounded, 1,000 dead on return voyage |

7 killed ~12 wounded |

||||||

The Battle of Québec was a big fight in October 1690. It happened between the colonies of New France (which is now part of Canada) and Massachusetts Bay (part of the future United States). These colonies were ruled by France and England. This battle was the very first time the city of Québec had to defend itself from an attack.

During a conflict known as King William's War, the English colonists from New England had already captured Port Royal in Acadia. After this win, they hoped to take Québec, which was the main city of New France. The loss of Port Royal really worried the French colonists, called Canadiens. Their leader, Governor-General Louis de Buade de Frontenac, quickly ordered the city to get ready for a siege (when an army surrounds a place to try and capture it).

When the English sent people to demand that Québec surrender, Governor Frontenac famously said his only answer would come from "the mouth of my cannons." The English army, led by Major John Walley, landed near Beauport in the Québec area. However, French-Canadian soldiers kept bothering them until they had to leave. At the same time, the English ships, led by Sir William Phips, were almost destroyed by cannon fire from the city's high walls.

Both sides learned important lessons from this battle. The French made their city's defences much stronger. The English realized they needed more artillery (big guns) and better help from England if they ever wanted to capture Québec.

Contents

Why the Battle Happened

The colony of New France claimed a huge part of North America. However, it had far fewer people than its neighbors, New England and New York. By 1689, New France had only about 14,000 settlers. But most of these people lived in towns that were protected by strong forts.

Phips Attacks Acadia

In 1690, Sir William Phips was chosen by Massachusetts to lead an attack against French Acadia. He sailed with seven ships and about 450 soldiers. On May 21, Port Royal gave up. Its governor, Louis-Alexandre des Friches de Menneval, had only about 70 men and no working cannons. He couldn't fight back. Phips's men then took valuable items from the town and even damaged the church.

This victory worried the French colonists. They feared their capital city, Québec, would be next. In 1690, Québec didn't have very strong fortifications. The land side of the city, especially near the Plains of Abraham, was open to attack.

Québec Prepares for a Fight

Count Frontenac returned to Canada as Governor-General for a second time. He quickly ordered a wooden fence, called a palisade, to be built around the city. This fence stretched from the fort at the Château Saint-Louis to the Saint-Charles River. A military officer named Major Provost oversaw the building of eleven small stone forts, called redoubts, along this fence. These would help protect against cannons.

The strongest part of the land defences was a windmill called Mont-Carmel. It had three cannons ready to fire. The fence ended near the hospital on the east side of the city. The cannons facing the river were also improved. Eight guns were placed near the Château, and six large 18-pounder cannons were set up at the docks. Temporary barriers were also put on the street leading to the upper part of the city.

Schuyler's Diversion Fails

Meanwhile, a group of 150 soldiers from Albany and Iroquois warriors, led by Captain John Schuyler, traveled overland to Montréal. They used "petite guerre" tactics, which meant long trips into enemy land to surprise them. Schuyler's plan was to capture Montréal and keep French soldiers busy there. This would allow the English ships from Boston to attack Québec without problems.

However, sickness, lack of supplies, and disagreements among the leaders caused most of the soldiers and Iroquois to turn back. Schuyler was left with only a small part of the 855 men he was promised. On September 4, the English raiders attacked small towns south of Montréal, killing about 50 French settlers. Schuyler's group was too weak to fight the main army in Montréal. So, the English invasion ended, and they went home.

Because Schuyler's attack failed, Governor Frontenac was able to order soldiers from Montréal and Trois-Rivières to rush to Québec. Four days later, Frontenac arrived in Québec with 200 to 300 soldiers. This greatly boosted the city's spirits and their will to fight.

Phips Arrives at Québec

While the English colonies sent a group overland to Montréal (which didn't achieve much), Massachusetts launched a separate attack on Québec. The whole operation was paid for by special paper money, which was supposed to be paid back with the valuable items taken from Québec.

The English Fleet's Journey

The English expedition had about 32 ships, but only four of them were large. Over 2,300 soldiers from Massachusetts were part of the force. Sir Phips, who had won at Port Royal, was in charge. Their departure was delayed until late summer because they were waiting for more ammunition from England, which never came. So, when Phips's group left Hull, Massachusetts on August 20, they didn't have enough ammunition.

Bad weather, strong winds, and a lack of expert pilots who knew the Saint Lawrence River slowed them down. Phips didn't finally drop anchor in the Québec area until October 16.

Frontenac's Confidence

Frontenac, who was a clever and experienced officer, reached Québec from Montréal on October 14. When all the local soldiers he had called for arrived, he had nearly 3,000 men to defend the city. The English had been "quite confident that the cowardly and effete French would be no match for their hardy men." But in reality, the French were ready.

Frontenac felt confident because he had three groups of trained soldiers. These were much better than Phips's amateur soldiers. As it turned out, these trained soldiers weren't even needed. The local French-Canadian soldiers were able to push back Phips's landing parties. Also, the city itself was "sited on the strongest natural position they [the English officers] had likely ever seen." Québec had impressive cliffs and Cape Diamond. The eastern shore was also very shallow, meaning ships couldn't get close, and smaller boats would be needed to land soldiers.

A Bold Demand and a Famous Reply

On October 16, Phips sent Major Thomas Savage to deliver a message demanding Québec's surrender. Before the meeting, Frontenac had Phips's messengers blindfolded. He led them through noisy crowds in the streets of Québec. This was a trick to make it seem like he had more soldiers than he really did.

Then, in the Château Saint-Louis, Frontenac and many of his officers, dressed in their best uniforms, listened to the English messenger. Major Savage tried his best to deliver Phips's demand. The message, written by strict English Puritans, started very seriously. It said that the war between England and France, and the attacks by the French and their Native American allies on New England, forced them to come and take Québec for their own safety.

The English messenger told them they had one hour to agree and then pulled out his watch. Frontenac was so angry that he wanted to hang the messenger right there, where the English fleet could see. Only the Bishop of Québec, François de Laval, managed to calm him down. When asked for a written reply, Frontenac famously shot back:

Non, je n'ai point de réponse à faire à votre général que par la bouche de mes canons et de mes mousquets.

(I have no reply to make to your general other than from the mouths of my cannons and muskets.)

Major Savage was relieved to be blindfolded again and led back to his ship. Phips's war council was very upset by this answer. They had expected to find a city that was scared and undefended. That evening, drums and fifes were heard approaching Québec. Then, loud cheers came from the town. Louis-Hector de Callière had arrived with the rest of the Montréal soldiers.

The Battle Begins

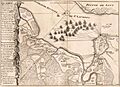

The English saw that the only possible weak spot in Québec's defences was on the city's northeastern side. Their plan was to land their main force on the Beauport shore, east of the Saint Charles River. This force would then cross the river in the fleet's boats, bringing their field guns with them. Once these soldiers were on the high ground west of Québec, the fleet would attack the city and land a second group of soldiers there.

Frontenac had expected the land attack to come from Beauport. So, the riverbanks on the southwestern side were already built up with military defences. He planned to only have small fights there, keeping his trained soldiers ready for a big battle on the open ground west of Québec.

However, the big battle never happened. The 1,200 English soldiers, led by Major John Walley (Phips's second-in-command), never managed to cross the Saint Charles River. Frontenac had sent strong groups of Canadian soldiers, led by Jacques Le Moyne de Sainte-Hélène, along with some First Nations warriors, into the wooded areas east of the river.

When the English landed on October 18, the Canadian soldiers immediately started bothering them. Meanwhile, the ships' boats mistakenly landed the field guns on the wrong side of the Saint Charles River. At the same time, Phips's four large ships, going against the plan, anchored in front of Québec. They began firing at the city until October 19, when they had used up most of their ammunition.

The French cannons on shore were also very strong. They pounded the English ships until their rigging (ropes and masts) and hulls (the main body of the ship) were badly damaged. The flag of Phips's main ship, the Six Friends, was shot down and fell into the river. Under a rain of musket shots, a brave group of Canadians paddled a canoe up to the ships and captured the flag. They brought it back to the Governor in triumph.

Land Force Retreats

During the naval attack, the land force under Walley did nothing. They were cold and complained about not having enough rum. After a couple of miserable days, they decided to try and take the shore positions and overcome the French earthworks. On October 20, they set out "in the best European tradition, with drums beating and colors unfurled." But there was a fight at the edge of the woods.

The English soldiers could not handle the constant, heavy fire from the Canadians. Their brass field guns, fired into the woods, had no effect. Although Sainte-Hélène was badly wounded and later died, 150 of the English attackers were killed. They became completely discouraged. On October 22, they retreated in a state of panic, even leaving five of their field guns on the shore.

What Happened Next

On October 23 and 24, the two sides agreed to exchange prisoners. After that, the English ships sailed back to Boston. Phips's own report said only 30 English soldiers died in the fighting. However, sickness (like smallpox) and accidents at sea caused about 1,000 more deaths. James Lloyd of Boston wrote in January that "7 vessels yet wanting 3 more cast away & burnt." Cotton Mather told how one ship was wrecked on Anticosti. Its crew survived on the island through the winter and were rescued the next summer by a ship from Boston.

Phips's defeat was complete and a disaster. Luckily for the French, they didn't have enough food to feed the large army they had gathered to defend Québec if the siege had lasted longer. Phips himself didn't show any natural military skills to make up for his lack of experience. However, some argue that the expedition was doomed from the start because it lacked trained soldiers and enough supplies. Governor Henry Sloughter of New York described the mood in the English colonies when he wrote that the whole country was "extremely hurt by the late ill managed and fruitless expedition to Canada." He said it caused a debt of £40,000 and about 1,000 men were lost to sickness and shipwrecks, with "no blow struck for want of courage and conduct in the Officers."

French Victory and Improvements

Canada celebrated its victory and survival. On November 5, a special church service was held in Québec. The chapel was later named Notre Dame de la Victoire, meaning "Our Lady of Victory." When news of the expedition reached the Palace of Versailles in France, King Louis XIV ordered a special medal to be made. It said: Kebeca liberata M.DC.XC–Francia in novo orbe victrix, which means "Deliverance of Québec 1690–France victorious in the New World."

Jacques Le Moyne, who died soon after the battle, was greatly missed by everyone in the colony because he was polite and brave. The Onondaga Iroquois sent a special beaded belt as a sign of sympathy. They also released two prisoners to honor his memory. His brother, Charles Le Moyne, became famous for his part in the battle. He later received more land for his service and became the first Baron de Longueuil.

Both sides learned from the battle. The French victory showed that to take Québec, the cannons of "Old England would have to be brought in." Similarly, Frontenac realized the city's defences needed a lot of improvement. In 1692, he gave a military engineer named Josué Berthelot de Beaucours the job of designing a fortress that could stand up to a European-style siege.

Work on these new defences began in the summer of 1693. They built an earth wall with large strong points called bastions to surround the city. Pointed wooden stakes were placed on top of the walls. A complete shore battery, known as the "Royal battery," was built right after the siege. It was shaped like a small bastion and had 14 openings for cannons to cover both sides of the Saint Lawrence River and the river itself.

Although another expedition was launched against Québec during Queen Anne's War, it failed to reach its target. Many ships were wrecked with great loss of life in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Québec's improved defences would not be truly tested again until the Battle of the Plains of Abraham in 1759.

Images for kids

-

In 1690, Sir William Phips was appointed the major-general of Massachusetts, to command an expedition against Acadia.

-

"I have no reply to make to your general other than from the mouth of my cannons and muskets." Frontenac famously rebuffs the English envoys. Watercolour on commercial board.

| Misty Copeland |

| Raven Wilkinson |

| Debra Austin |

| Aesha Ash |