Irish Canadians facts for kids

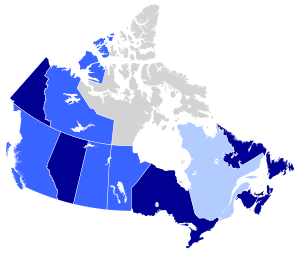

Irish Canadians as percent of population by province/territory

|

|

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 4,627,000 13.4% of the Canadian population (2016) |

|

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 2,095,460 | |

| 675,135 | |

| 596,750 | |

| 446,215 | |

| 201,655 | |

| 135,835 | |

| 106,225 | |

| Languages | |

| English · French · Irish (historically) | |

| Religion | |

|

|

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Irish, Ulster-Scots, English Canadians, Scottish Canadians, Welsh Canadians, Irish Americans, Scotch-Irish Canadians | |

Irish Canadians (Irish: Gael-Cheanadaigh) are Canadian citizens who have full or partial Irish family roots. This includes people whose ancestors came from Ireland. About 1.2 million Irish immigrants arrived in Canada between 1825 and 1970. More than half of them came between 1831 and 1850.

By 1867, Irish Canadians were the second largest ethnic group in Canada, after the French. They made up 24% of Canada's population. In 1931, the national census counted 1,230,000 Canadians of Irish descent. Half of these people lived in Ontario. About one-third were Catholic and two-thirds were Protestant.

Most Irish immigrants were Protestant before the Irish famine in the late 1840s. After the famine, many more Catholics than Protestants arrived. Even more Catholics went to the United States. Others went to Great Britain and Australia.

In the 2016 Canadian census, 4,627,000 Canadians said they had full or partial Irish ancestry. This is about 13.43% of the total population. Irish Canadians are part of a larger group called British Canadians.

Contents

- History of Irish Canadians

- Irish Canadian Population

- Where Irish Canadians Live

- See also

History of Irish Canadians

| Irish Canadian Population History |

||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

| 1871 | 846,414 | — |

| 1881 | 957,403 | +13.1% |

| 1901 | 988,721 | +3.3% |

| 1911 | 1,074,738 | +8.7% |

| 1921 | 1,107,803 | +3.1% |

| 1931 | 1,230,808 | +11.1% |

| 1941 | 1,267,702 | +3.0% |

| 1951 | 1,439,635 | +13.6% |

| 1961 | 1,753,351 | +21.8% |

| 1971 | 1,581,730 | −9.8% |

| 1981 | 1,151,955 | −27.2% |

| 1986 | 3,622,290 | +214.4% |

| 1991 | 3,783,355 | +4.4% |

| 1996 | 3,767,610 | −0.4% |

| 2001 | 3,822,660 | +1.5% |

| 2006 | 4,354,155 | +13.9% |

| 2011 | 4,544,870 | +4.4% |

| 2016 | 4,627,000 | +1.8% |

| Source: Statistics Canada Note1: 1981 Canadian census did not include multiple ethnic origin responses, thus population is an undercount. Note2: 1996-present census populations are undercounts, due to the creation of the "Canadian" ethnic origin category. |

||

Early Irish Arrivals

The first time Irish people were recorded in what is now Canada was in 1536. Irish fishermen from Cork traveled to Newfoundland.

Irish people began to settle permanently in Newfoundland in the late 1700s and early 1800s. Most of them came from Waterford and Wexford. After the War of 1812, more Irish people started coming to other parts of Canada. This was a big part of The Great Migration of Canada.

Between 1825 and 1845, 60% of all immigrants to Canada were Irish. In 1831 alone, about 34,000 Irish people arrived in Montreal.

From 1830 to 1850, 624,000 Irish people arrived. At the end of this time, the population of the Canadian provinces was 2.4 million. Many arrived in Upper Canada (now Ontario), Lower Canada (Quebec), and the Maritime provinces like Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and New Brunswick. Saint John was a very common arrival point. Not all of them stayed in Canada. Many moved to the United States or to Western Canada later on. Few returned to Ireland.

During the Great Famine in Ireland (1845–52), Canada welcomed many very poor Irish Catholics. They left Ireland because of terrible conditions. Landowners in Ireland sometimes forced tenants to leave. They would put them on empty lumber ships returning to Canada. Others paid for their trips. Many also left on ships from crowded docks in Liverpool and Cork.

Most Irish immigrants who came to Canada and the United States in the 1800s spoke Irish. Many did not know any other language when they arrived.

Where Irish Immigrants Settled

Most Irish Catholics arrived at Grosse Isle. This was an island in Quebec in the St. Lawrence River. It was an immigration reception station. Thousands of people died or arrived sick in the summer of 1847. The hospital there was only set up for less than 100 patients. Many ships that reached Grosse-Île had lost most of their passengers and crew. Many more died in quarantine on or near the island.

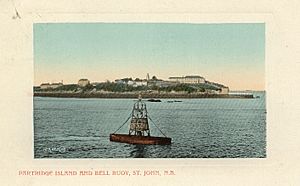

From Grosse-Île, most survivors were sent to Quebec City and Montreal. The Irish communities in these cities grew larger. Orphaned children were adopted by Quebec families. They learned to speak French and became part of Québécois culture. At the same time, ships carrying starving people also docked at Partridge Island, New Brunswick. Conditions there were just as desperate.

Many families who survived continued their journey to Canada West (now Ontario). They provided cheap labor and helped settle land in a fast-growing economy. This happened in the decades after they arrived.

Compared to Irish people who went to the United States or Britain, many Irish arrivals in Canada settled in rural areas. They also settled in cities.

Catholic Irish and Protestant (Orange) Irish often had conflicts from the 1840s. In Ontario, the Irish and French groups disagreed over who should control the Catholic Church. The Irish group was successful. In this case, the Irish sided with Protestants to oppose French-language Catholic schools.

Thomas D'Arcy McGee, an Irish-Montreal journalist, became one of the Fathers of Confederation in 1867. He was an Irish Republican when he was younger. Later, he changed his views and strongly supported Confederation. He helped make sure that Catholics, as a minority group, had educational rights in the Canadian Constitution. In 1868, he was killed in Ottawa. Historians are not sure who killed him or why. One idea is that a Fenian, Patrick James Whelan, was the killer. This was because McGee had spoken against Fenian raids. Others believe Whelan was wrongly blamed.

After Confederation, Irish Catholics faced more challenges. This was especially true from Protestant Irish in Ontario. This group was strongly influenced by the anti-Catholic Orange Order. The song "The Maple Leaf Forever" was written by a Scottish immigrant and Orangeman, Alexander Muir. It showed a pro-British Ulster loyalism view typical of the time. It also showed dislike for Irish Republicanism. This feeling grew stronger with the Fenian Raids. As Irish people became more successful and new groups arrived in Canada, tensions lessened through the late 1800s.

Between 1815 and 1867, over 150,000 immigrants from Ireland arrived in Saint John, New Brunswick. The earlier arrivals were often skilled workers. Many stayed in Saint John and helped build the city. When the Great Famine happened between 1845 and 1852, many refugees arrived. It's thought that between 1845 and 1847, about 30,000 people arrived. This was more people than lived in the city at the time. In 1847, called "Black 47," about 16,000 immigrants, mostly from Ireland, arrived at Partridge Island. This was an immigration and quarantine station at the mouth of Saint John Harbour.

Irish Canadian Population

Note1: 1981 Canadian census did not include multiple ethnic origin responses, thus population is an undercount.

Note2: 1996-present census populations are undercounts, due to the creation of the "Canadian" ethnic origin category.

Note1: 1981 Canadian census did not include multiple ethnic origin responses, thus population is an undercount.

Note2: 1996-present census populations are undercounts, due to the creation of the "Canadian" ethnic origin category.

| Year | Population | % of total population |

|---|---|---|

| 1871 |

846,414 | 24.282% |

| 1881 |

957,403 | 22.137% |

| 1901 |

988,721 | 18.407% |

| 1911 |

1,074,738 | 14.913% |

| 1921 |

1,107,803 | 12.606% |

| 1931 |

1,230,808 | 11.861% |

| 1941 |

1,267,702 | 11.017% |

| 1951 |

1,439,635 | 10.276% |

| 1961 |

1,753,351 | 9.614% |

| 1971 |

1,581,730 | 7.334% |

| 1981 |

1,151,955 | 4.783% |

| 1986 |

3,622,290 | 14.476% |

| 1991 |

3,783,355 | 14.016% |

| 1996 |

3,767,610 | 13.207% |

| 2001 |

3,822,660 | 12.897% |

| 2006 |

4,354,155 | 13.937% |

| 2011 |

4,544,870 | 13.834% |

| 2016 |

4,627,000 | 13.427% |

The graphs above do not include people who have only some Irish ancestry. One journalist, Louis-Guy Lemieux, believes that about 40% of Quebecers have Irish roots on at least one side of their family. Protestant English-speakers sometimes avoided Catholic Irish. So, it was common for Catholic Irish to settle among and marry Catholic French-speakers. Many other Canadians also have Irish roots. This means the total number of Canadians with some Irish ancestry is a large part of the Canadian population.

Religion and Community Life

Protestant and Catholic Differences

In the 1800s, there were often conflicts between Irish Protestants and Irish Catholics in Canada. This was especially true in Atlantic Canada and Ontario. These conflicts sometimes led to violence.

The Orange Order was a group that was anti-Catholic and very loyal to Britain. It was very strong in Ontario. Its members were mostly Protestant Irish settlers. The Orange Order played a big role in the political, social, and religious lives of its followers. As Irish Protestant settlers moved north and west from Lake Ontario, Orange lodges were built. Even if the number of active members was sometimes overestimated, the Orange Order had a lot of influence. This influence was similar to that of Catholic groups in Quebec.

In Montreal in 1853, the Orange Order organized speeches by Alessandro Gavazzi. He was a former priest who was strongly anti-Catholic and anti-Irish. This led to a violent fight between Irish and Scottish groups. St. Patrick's Day parades in Toronto often had problems because of these tensions. They got so bad that the mayor canceled the parade permanently in 1878. It was not brought back until 1988. The Jubilee Riots of 1875 shook Toronto when religious tensions were at their highest. Irish Catholics in Toronto were a small group among a larger Protestant population. Many of these Protestants were Irish and strongly supported the Orange Order.

Where Irish Canadians Live

| Province/Territory | 2016 | 2011 | 2006 | 2001 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | |

| 2,095,465 | 15.82% | 2,069,110 | 16.35% | 1,988,940 | 16.53% | 1,761,280 | 15.61% | |

| 675,130 | 14.8% | 643,470 | 14.88% | 618,120 | 15.17% | 562,895 | 14.55% | |

| 596,750 | 15% | 565,120 | 15.84% | 539,160 | 16.56% | 461,065 | 15.68% | |

| 446,210 | 5.6% | 428,570 | 5.54% | 406,085 | 5.46% | 291,545 | 4.09% | |

| 156,145 | 12.59% | 155,455 | 13.24% | 151,915 | 13.4% | 143,950 | 13.04% | |

| 155,725 | 14.55% | 156,655 | 15.53% | 145,475 | 15.25% | 139,205 | 14.45% | |

| 195,865 | 21.56% | 201,655 | 22.25% | 195,365 | 21.63% | 178,585 | 19.9% | |

| 147,245 | 20.15% | 159,195 | 21.63% | 150,705 | 20.94% | 135,835 | 18.87% | |

| 106,220 | 20.74% | 110,370 | 21.76% | 107,390 | 21.45% | 100,260 | 19.73% | |

| 38,505 | 27.57% | 41,715 | 30.37% | 39,170 | 29.19% | 37,170 | 27.87% | |

| 5,060 | 12.3% | 4,845 | 11.88% | 4,860 | 11.84% | 4,470 | 12.05% | |

| 6,930 | 19.74% | 7,315 | 21.95% | 5,735 | 18.99% | 5,455 | 19.12% | |

| 1,740 | 4.89% | 1,385 | 4.37% | 1,220 | 4.16% | 950 | 3.56% | |

| 4,627,000 | 13.43% | 4,544,870 | 13.83% | 4,354,155 | 13.94% | 3,822,660 | 12.9% | |

Irish Communities in Quebec

Irish people created communities in both cities and rural areas of Quebec. Many Irish immigrants arrived in Montreal during the 1840s. They were hired as workers to build the Victoria Bridge. They lived in a tent city at the base of the bridge. Here, workers found a mass grave of 6,000 Irish immigrants. These people had died at nearby Windmill Point during a typhus outbreak in 1847–48. The Irish Commemorative Stone, also known as the "Black Rock," was put up by bridge workers to remember this sad event.

The Irish then settled permanently in working-class neighborhoods like Pointe-Saint-Charles, Verdun, Saint-Henri, Griffintown, and Goose Village, Montreal. With help from Quebec's Catholic Church, they built their own churches, schools, and hospitals. St. Patrick's Basilica was founded in 1847. It served Montreal's English-speaking Catholics for over a century. Loyola College was started by the Jesuits in 1896 to serve Montreal's mostly Irish English-speaking Catholic community. Saint Mary's Hospital was founded in the 1920s. It still serves Montreal's English-speaking population today.

The St. Patrick's Day Parade in Montreal is one of the oldest in North America. It started in 1824. Each year, it brings in crowds of over 600,000 people.

Many Irish also settled in Quebec City. They created communities in rural Quebec, especially in Pontiac, Gatineau, and Papineau. These areas had an active timber industry. However, most later moved to larger North American cities.

Today, many Québécois have some Irish family history. Examples include political leaders like Laurence Cannon and Claude Ryan. Former Premiers Daniel Johnson and Jean Charest also have Irish roots. So do Georges Dor (born Georges-Henri Dore) and former Prime Ministers Louis St. Laurent and Brian Mulroney. The Irish are the second largest ethnic group in Quebec, after French Canadians.

Irish Communities in Ontario

Irish people had been coming to Ontario in small numbers since the 1600s and 1700s. They served New France as missionaries, soldiers, mapmakers, and fur trappers. After British North America was created in 1763, Protestant Irish began moving to Upper Canada. Some were United Empire Loyalists or came directly from Ulster.

After the War of 1812, more Irish people, including a growing number of Catholics, came to Canada. They sought work on projects like canals, roads, early railroads, and in the lumber industry. These workers were called 'navvies'. They built much of the early infrastructure in the province. Programs offering cheap or free land brought over farming families. Many of these families were from Munster (especially Tipperary and Cork). Peter Robinson organized land settlements for Catholic tenant farmers in the 1820s. These settlements were in rural Eastern Ontario. This helped make Peterborough an important regional center.

The Irish were very important in building the Rideau Canal and settling along its path. Thousands of Irish, along with French-Canadians, worked in tough conditions. Hundreds, even thousands, died from diseases like malaria.

Impact of the Irish Famine

The Great Irish Hunger (1845–1849) had a big effect on Ontario. In the summer of 1847, many sick immigrants arrived on steamers from Quebec. They came to Bytown (now Ottawa) and ports on Lake Ontario, like Kingston and Toronto. They also came to many smaller towns in southern Ontario. Quarantine centers were quickly built to help them. Nurses, doctors, priests, nuns, fellow Irish people, some politicians, and regular citizens helped them. Thousands died in Ontario that summer, mostly from typhus.

How long settlers stayed depended on their situation. For example, Irish immigration to North Hastings County, Canada West, happened after 1846. Most immigrants were drawn to North Hastings by free land grants starting in 1856. Three Irish settlements were created: Umfraville, Doyle's Corner, and O'Brien Settlement. The Irish were mainly Roman Catholic. Crop failures in 1867 stopped the road building program near the Irish settlements. After this, more settlers left than arrived. By 1870, only the successful settlers remained, mostly farmers who raised animals.

In the 1840s, a big challenge for the Catholic Church was keeping the loyalty of very poor Catholic newcomers. There was a fear that Protestants might use their needs to try and convert them. To respond, the Church built many charities like hospitals, schools, and orphanages. These helped meet needs and keep people in the Catholic faith. The Catholic church had less success dealing with tensions between its French and Irish clergy. Eventually, the Irish gained more control.

Social Changes and Integration

Toronto had similar numbers of both Irish Protestants and Irish Catholics. Riots and conflicts often happened from 1858 to 1878. These occurred during the annual St. Patrick's Day parade or other religious events. This led to the Jubilee Riots of 1875. These tensions increased after the Fenian Raids, which were organized but failed attacks along the American border. This made Protestants suspicious of Catholics' support for the Fenian cause.

The Irish population mostly made up the Catholic population in Toronto until 1890. After that, German and French Catholics were welcomed. Still, the Irish were 90% of the Catholic population. However, strong efforts like the founding of St. Michael's College in 1852, three hospitals, and major charities like the Society of St. Vincent de Paul and House of Providence helped strengthen Irish identity. These groups transformed the Irish presence in the city into one of influence and power.

From 1840 to 1860, violence between different religious groups was common in Saint John, New Brunswick. This led to some of the worst city riots in Canadian history. Orange Order parades often ended in riots with Catholics, many of whom spoke Irish. They fought against being pushed to the edges of society in Irish neighborhoods like York Point and North End areas. Protestant groups gained control over the city's political system during the famine. This changed the city's population greatly with waves of immigration. In just three years, from 1844 to 1847, 30,000 Irish people came to Partridge Island, a quarantine station in the city's harbor.

An economic boom after their arrival helped many Irish men find steady jobs. They worked on the fast-growing railroad network. Settlements grew along the Grand Trunk Railroad corridor, often in rural areas. This allowed many to farm the cheap, good land in southern Ontario. In cities like Toronto, jobs included construction, making alcohol, shipping on the Great Lakes, and manufacturing. Women usually worked in domestic service. In more distant areas, jobs were in the Ottawa Valley timber trade, which reached Northern Ontario. Railroad building and mining were also important.

There was a strong Irish presence in rural Ontario, unlike in the northern US. But they were also many in towns and cities. Later generations of these poorer immigrants became important in unions, business, law, arts, and politics.

Many of the one million immigrants, mostly British and Irish, who came to Canada in the mid-1800s benefited from available land. They also found fewer social barriers to moving up in society. This allowed them to feel like citizens of their new country in a way they couldn't back home.

Some historians argue that the Irish immigrant experience in Canada was different from that in America. They say that because Protestants were a larger part of the Irish group in Canada, and because many Irish lived in rural areas, urban ghettos didn't form as much. This allowed for easier social mobility. In contrast, Irish Americans in the Northeast and Midwest were mostly Catholic, lived in cities, and were often in ghettos. However, there were Irish-focused neighborhoods in Toronto, like Corktown and Cabbagetown, especially after the famine. These areas existed until the 1970s in some cases. This was also true in other Canadian cities with many Irish Catholics, such as Montreal, Ottawa, and Saint John.

Another idea is that the rise of the Knights of Labor helped Orange and Catholic Irish in Toronto overcome their old hatreds. They then formed a common working-class culture. However, some historians disagree. They argue that in Toronto's Irish neighborhoods, a mix of Irish rural culture and traditional Catholicism created a new, urban, religious identity. This culture spread from the city to the countryside and throughout Ontario. This created a somewhat closed Irish society. While Irish Catholics worked with others in labor groups for their families' future, they did not fully share a new working-class culture with their old Orange rivals.

Between 1890 and 1920, Catholics in Toronto experienced big social, cultural, and economic changes. These changes helped them fit into Toronto society and overcome their lower status. Irish Catholics (unlike French Catholics) strongly supported Canada's role in the First World War. They moved out of their old neighborhoods and lived in all parts of Toronto. They started as unskilled workers. But with good education, they moved up and were well represented in the lower middle class. They also married Protestants at a much higher rate than before.

Confederation and Beyond

With Canadian Confederation in 1867, Catholics were given their own school board. Through the late 1800s and early 1900s, Irish immigration to Ontario continued, but at a slower pace. Much of it was families joining relatives already there. Some Irish in Ontario moved away during this time due to economic problems. They also moved to new lands and mining areas in the US or Western Canada. The opposite happened after World War II. People of Irish descent from the Maritimes and Newfoundland moved to Ontario looking for work.

In 1877, something important happened in Irish Canadian Protestant-Catholic relations in London, Ontario. The Irish Benevolent Society was founded. It was a group of Irish men and women, both Catholic and Protestant. The society promoted Irish Canadian culture. But members were not allowed to talk about Irish politics during meetings. Today, the Society is still active.

Some writers thought that Irish people in 19th-century North America were poor. But records from 1892 show this wasn't true. Irish-born and Canadian-born Irish people gained wealth in similar ways. Being Irish was not an economic disadvantage by the 1890s. Immigrants from earlier decades might have had more economic problems. But generally, Irish people in Ontario in the 1890s had similar levels of wealth to the rest of the population.

By 1901, Irish Catholics and Scottish Presbyterians in Ontario were among the most likely to own homes. Anglicans did only moderately well, even though they were traditionally linked to Canada's elite. French-speaking Catholics in Ontario gained wealth and status less easily than Protestants and Irish Catholics. Even though there were differences in success between different religious groups, the difference between Irish Catholics and Irish Protestants in Canadian cities was quite small.

Irish Canadians in the 20th Century

One study found that supporting World War I helped Irish Catholics feel like loyal citizens. This helped them fit into Canadian society. Rev. Michael Fallon, the Catholic bishop of London, sided with Protestants against French Catholics. His main goal was to help Irish Catholics in Canada and around the world. He had strong support from the Vatican. He opposed French Canadian Catholics, especially by being against bilingual education. French Canadians did not join Fallon's efforts to support the war. They became less involved in Ontario politics and society.

During the Troubles (1969–1998) in Northern Ireland, Irish Canadians also reacted to the conflict, though not as strongly as Irish Americans. In August 1969, about 150 Irish Canadians in Toronto said they would send money. This money could be used to buy guns if needed, for Catholic women and children in the Bogside in Derry. After the conflict started, Irish Republican Clubs were set up in America and Canada. They supported the Provisional Irish Republican Army (PIRA) cause. Much of the IRA support in Canada was in Montreal, Toronto, and southern Ontario. Canadian IRA supporters raised money to secretly buy weapons. These included detonators from Canadian mining sites, for the IRA's armed actions.

At the same time, Irish Canadians also supported loyalist paramilitary groups (like the Ulster Volunteer Force and Ulster Defence Association). This was because of the large Ulster Protestant population in Ontario and Orange Lodges across the country. One sociologist said that Canadian support networks were "the main source of support for loyalism outside the United Kingdom." He added that "Ontario is to Ulster Protestants what Boston is to Irish Catholics." After the Troubles began, various Canadian loyalist groups formed. They aimed to give 'under attack' Protestants the resources to arm themselves. Between 1979 and 1986, loyalist groups received many weapons from Canadian sources. These weapons helped the loyalist armed actions and led to many Catholic civilian casualties.

Irish Canadian Life Today

Today, the big impact of 19th-century Irish immigration to Ontario is clear. Close to 2 million people in the province report Irish ancestry. This is almost half of all Canadians who claim Irish roots. In 2004, March 17 was declared "Irish Heritage Day" by the Ontario Legislature. This recognized the huge contributions of Irish people to the development of the Province.

Ontario has many people who are interested in the Irish language. Many see the language as part of their family heritage. Ontario is also home to Gaeltacht Bhuan Mheiriceá Thuaidh. This is a special area that hosts cultural activities for Irish speakers and learners. The Irish government has recognized it.

When Ireland's economy struggled in 2010, many Irish people came to Canada looking for work. Some had jobs already arranged.

Many communities in Ontario are named after places and family names from Ireland. These include Ballinafad, Ballyduff, Ballymote, Cavan, Dublin, Dundalk, Dunnville, Enniskillen, Erinsville, Galway, Limerick, Listowel, Lucan, Munster, Navan, New Dublin, Ripley, Shamrock, Tara, and Westport.

Irish Communities in New Brunswick

Saint John is often called "Canada's Irish City." Between 1815 and 1867, over 150,000 immigrants from Ireland arrived in Saint John. The earlier arrivals were mostly skilled workers. Many stayed in Saint John and helped build the city. But when the Great Famine raged between 1845 and 1852, huge numbers of famine refugees arrived. It's thought that between 1845 and 1847, about 30,000 people arrived. This was more than the city's population at the time. In 1847, called "Black 47," about 16,000 immigrants, mostly from Ireland, arrived at Partridge Island. This was the immigration and quarantine station at the mouth of Saint John Harbour.

After the British colony of Nova Scotia was divided in 1784, New Brunswick was first named New Ireland. Its capital was planned to be in Saint John.

By 1850, the Irish Catholic community was Saint John's largest ethnic group. In the 1851 census, over half of the heads of households in the city said they were born in Ireland. By 1871, 55% of Saint John's residents were Irish-born or had Irish fathers. However, the city was divided by tensions between Irish Catholics and Unionist Protestants. From the 1840s onward, conflicts between religious groups were common in the city. Many poor, Irish-speaking immigrants lived in crowded areas like York Point.

In 1967, St. Patrick's Square was created at Reed's Point to honor citizens of Irish heritage. The square looks out over Partridge Island. A copy of the island's Celtic Cross stands in the square. Then in 1997, the park was updated by the city. A memorial was put up by the city's St. Patrick's Society and Famine 150 group. It was revealed by Hon. Mary Robinson, who was the president of Ireland. The St. Patrick's Society of Saint John, founded in 1819, is still active today.

The Miramichi River valley received many Irish immigrants before the famine. These settlers were often better off and more educated than those who arrived later out of desperation. They came after the Scottish and French Acadians. They made their way in this new land, marrying Catholic Highland Scots and, less often, Acadians. Some, like Martin Cranney, held elected positions. They became natural leaders for their growing Irish community after the famine immigrants arrived. The early Irish came to the Miramichi because it was easy to get there. Lumber ships would stop in Ireland before returning to Chatham and Newcastle. The area also offered jobs, especially in the lumber industry. They commonly spoke Irish. In the 1830s and 1840s, there were many Irish-speaking communities along the New Brunswick and Maine border.

New Brunswick was a colony that exported timber for a long time. It became a destination for thousands of Irish immigrants who were fleeing the famines in the mid-1800s. This was because timber cargo ships offered cheap passage when returning empty to the colony. Quarantine hospitals were on islands at the mouth of the colony's two main ports: Saint John (Partridge Island) and Chatham-Newcastle (Middle Island). Many people died there. Those who survived settled on difficult farming lands in the Miramichi River valley and in the Saint John River and Kennebecasis River valleys. However, farming these areas was hard. So, many Irish immigrant families moved to the colony's major cities within a generation. Some also moved to Portland, Maine or Boston.

Saint John and Chatham, New Brunswick saw many Irish migrants. This changed the nature of both cities. Today, the city of Miramichi still hosts a large annual Irish festival. Miramichi is one of the most Irish communities in North America, perhaps second only to Saint John or Boston.

Like in Newfoundland, the Irish language was spoken in New Brunswick communities into the 1900s. The 1901 census asked about people's mother tongue, meaning the language commonly spoken at home. Several individuals and some families in the census said Irish was their first language and was spoken at home. These people had less in common in other ways; some were Catholic and some Protestant.

Irish Communities in Prince Edward Island

For many years, Prince Edward Island was divided between Irish Catholics and British Protestants. This included Ulster Scots from Northern Ireland. In the latter half of the 1900s, this division lessened. It ended completely after two events. First, the Catholic and Protestant school boards combined into one public system. Second, the practice of electing two members for each provincial area (one Catholic and one Protestant) was stopped.

Prince Edward Island History

According to Professor Brendan O'Grady, a history professor at the University of Prince Edward Island, most Irish immigrants had already arrived on Prince Edward Island before the Great Famine of 1845–1852. During the famine, a million Irish people died and another million left Ireland. Only one coffin ship landed on the Island in 1847.

The first waves of Irish immigrants came between 1763 and 1880. During this time, ten thousand Irish immigrants arrived on the Island. From 1800 to 1850, "10,000 immigrants from every county in Ireland" had settled in Prince Edward Island. By 1850, they made up 25% of the Island's population.

After 1763, the British divided St. John's Island into many lots. These were given to "influential individuals in Britain." One condition for owning land was that each lot had to be settled by British Protestants by 1787.

From 1767 through 1810, English-speaking Irish Protestants were brought to the colony. They were meant to help set up the British system of government, its institutions, and laws. The Irish-born Captain Walter Patterson was the first Governor of St. John's Island from 1769 until 1787. According to the Dictionary of Canadian Biography, the "land question" that lasted a century began because Patterson failed as an administrator. The colony's lands were owned by a few British landlords who lived elsewhere. These landlords demanded rent from their Island tenants.

In May 1830, the first ship of families from County Monaghan, in Ulster, Ireland, arrived on the Island. They were with Father John MacDonald, who had helped them come. They settled in Fort Augustus, on lands Father John MacDonald had inherited from his father. From the 1830s through 1848, 3,000 people moved from County Monaghan to PEI. This became known as the Monaghan settlements. This group was the largest number of Irish to arrive on the Island in the first half of the 1800s.

Irish Communities in Newfoundland

The large Irish Catholic population in Newfoundland in the 1800s played a big role in Newfoundland's history. They developed their own strong local culture. They often had political conflicts, sometimes violent, with the Protestant Scots-Irish "Orange" group.

In 1806, The Benevolent Irish Society (BIS) was founded in St. John's, Newfoundland. It was a charity for local people of Irish birth or ancestry, no matter their religion. The BIS was a friendly, middle-class group that aimed to help the poor learn skills to improve their lives. Today, the society is still active in Newfoundland. It is the oldest charity in North America.

Newfoundland Irish Catholics, mostly from southeast Ireland, settled in cities. These were mainly St. John's and parts of the nearby Avalon Peninsula. British Protestants, mostly from the West Country, settled in small fishing communities. Over time, the Irish Catholics became wealthier than their Protestant neighbors. This encouraged Protestant Newfoundlanders to join the Orange Order. In 1903, Sir William Coaker founded the Fisherman's Protective Union in an Orange Hall. Also, during the time of Commission of Government (1934–1949), the Orange Lodge was one of the few "democratic" groups in the Dominion of Newfoundland.

In 1948, a referendum was held in Newfoundland to decide its political future. Irish Catholics mostly supported Newfoundland becoming independent again, as it was before 1934. Protestants mostly supported joining the Canadian Confederation. Newfoundland then joined Canada by a 52–48% vote. After the east coast cod fishery closed in the 1990s, many Protestants moved to St. John's. Now, the main issues are about rural versus urban interests, rather than ethnic or religious ones.

The Irish brought many common family names from southeast Ireland to Newfoundland. These include Walsh, Power, Murphy, Ryan, Whelan, Phelan, O'Brien, Kelly, Hanlon, Neville, and others. Irish place names are less common. Many of the island's famous landmarks were already named by early French and English explorers. Still, places like Ballyhack, Cappahayden, Kilbride, St. Bride's, Port Kirwan, Waterford Valley, Windgap, and Skibereen in Newfoundland show Irish origins.

Along with traditional names, the Irish brought their native language. Newfoundland is the only place outside Europe with its own special name in the Irish language: Talamh an Éisc, meaning "the land of fish." Eastern Newfoundland was one of the few places outside Ireland where the Irish language was spoken by most people as their main language. Newfoundland Irish came from the Munster dialect. Older people still used it in the first half of the 1900s. It has influenced Newfoundland English in words (like angishore and sleveen) and grammar.

The family names, looks, main Catholic religion, and common Irish music in Newfoundland remind people so much of rural Ireland. Irish author Tim Pat Coogan called Newfoundland "the most Irish place in the world outside of Ireland."

The United Irish Uprising happened in April 1800 in St. John's, Newfoundland. Up to 400 Irishmen had secretly taken an oath to the Society of the United Irishmen. This rebellion in the Colony of Newfoundland was the only one the British government directly linked to the Irish Rebellion of 1798. The uprising in St. John's was important because it was the first time Irish people in Newfoundland openly challenged the government. The British feared it might not be the last. It gave Newfoundland a reputation as a Transatlantic Tipperary—a distant but partly Irish colony with a chance of political problems. Seven Irishmen were hanged by the crown because of the uprising.

According to the 2001 Canadian census, the largest ethnic group in Newfoundland and Labrador is English (39.4%). This is followed by Irish (39.7%), Scottish (6.0%), French (5.5%), and First Nations (3.2%). While half of all people also said their ethnicity was "Canadian," 38% said their ethnicity was "Newfoundlander" in a 2003 survey.

The largest single religious group in 2001 was the Roman Catholic Church, with 36.9% of the province's population (187,405 members). The main Protestant groups made up 59.7% of the population. The largest Protestant group was the Anglican Church of Canada at 26.1% (132,680 members). The United Church of Canada was 17.0% (86,420 members), and the Salvation Army was 7.9% (39,955 members). Other Protestant groups were much smaller. The Pentecostal Church made up 6.7% of the population with 33,840 members. Non-Christians were only 2.7% of the total population. Most of them said they had "no religion" (2.5% of the total population).

According to the 2006 Statistics Canada census, 21.5% of Newfoundlanders claim Irish ancestry. Other major groups in the province include 43.2% English, 7% Scottish, and 6.1% French. In 2006, Statistics Canada listed the following ethnic origins in Newfoundland: 216,340 English, 107,390 Irish, 34,920 Scottish, 30,545 French, 23,940 North American Indian, and so on.

Most Irish migration to Newfoundland happened before the famine (late 1700s and early 1800s). Two centuries of being isolated have led many people of Irish descent in Newfoundland to see their ethnic identity as "Newfoundlander," not "Irish." However, they are aware of the cultural links between the two.

Irish Communities in Nova Scotia

About one in four people in Nova Scotia has Irish ancestry. There are good resources for people who want to trace their family history.

Many Nova Scotians who say they have Irish ancestry are of Presbyterian Ulster-Scottish descent. William Sommerville (1800–1878) was a minister in the Irish Reformed Presbyterian Church. In 1831, he was sent as a missionary to New Brunswick. There, with missionary Alexander Clarke, he formed the Reformed Presbytery of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia in 1832. He then became a minister in Grafton, Nova Scotia, in 1833. Even though he was a strict Covenanter, Sommerville first ministered to Presbyterians generally over a very large area. Presbyterian centers included Colchester County, Nova Scotia.

Catholic Irish settlement in Nova Scotia was mostly in the Halifax city area. Halifax, founded in 1749, was estimated to be about 16% Irish Catholic in 1767. By the end of the 1700s, it was about 9%. Even though strict laws against them were usually not enforced, Irish Catholics had no legal rights in the early history of the city. There were no Catholic members in the legislature until near the end of the century. In 1829, Lawrence O'Connor Doyle, whose parents were Irish, became the first lawyer of his faith. He helped overcome opposition to the Irish.

There were also rural Irish village settlements throughout most of Guysborough County. Examples include the Erinville (meaning Irishville) /Salmon River Lake/Ogden/Bantry area. Bantry was named after Bantry Bay, County Cork, Ireland. This area was abandoned in the 1800s for better farmland. In this area, Irish last names are common. An Irish influence is clear in the accent, traditional music, food, religion (Roman Catholic), and some remaining traces of the Irish language. In Antigonish County, there are other villages with Irish origins. More can be found on Cape Breton Island, in places like New Waterford, Rocky Bay, and Glace Bay.

One historian notes that the popular idea of Cape Breton Island as only a Scottish Highland and Gaelic culture area is not completely accurate. It doesn't show the island's complex history since the 1500s. The original Mi'kmaq people, Acadian French, Lowland Scots, Irish, Loyalists from New England, and English have all contributed to its history. This history includes cultural, religious, and political conflicts, as well as cooperation and blending. The Highland Scots became the largest group in the early 1800s, and their heritage still exists, though less strongly.

Irish Communities in the Prairies

Some Canadian politicians hoped that helping Irish settlers move to Canada's prairies would create a 'New Ireland'. Or at least, it would show Canada as a good place for immigrants. But neither of these things happened. One study looks at the efforts of Quaker helper James Hack Tuke in the 1880s. It also looks at Thomas Connolly, the Irish emigration agent for the Canadian government. The Irish newspapers kept warning potential emigrants about the dangers and hardships of life in Canada. They encouraged people to settle in the United States instead.

Irish migration to the Prairie Provinces had two different parts. Some came through eastern Canada or the United States. Others came directly from Ireland. Many of the Irish-Canadians who came west were already quite settled. They spoke English and understood British customs and laws. They were often seen as part of English Canada. However, this was complicated by religious differences. Many of the first "English" Canadian settlers in the Red River Colony were strong Irish Loyalist Protestants and members of the Orange Order. They clashed with Catholic Métis leader Louis Riel's temporary government during the Red River Rebellion. As a result, Thomas Scott was executed. This made religious tensions worse in the east.

At this time and in the decades that followed, many Catholic Irish fought for separate Catholic schools in the west. But sometimes they disagreed with the French-speaking part of the Catholic community during the Manitoba Schools Question. After World War I and the unofficial solution to the religious schools issue, any Irish-Canadians from the east who moved west completely blended into the main society. The small group of Irish-born people who arrived in the second half of the 1900s were usually city professionals. This was very different from the farming pioneers who came before them.

About 10% of Saskatchewan's population between 1850 and 1930 were Irish-born or of Irish origin. One study shows that the Irish were a relatively privileged group. The most visible signs of Irish ethnicity across generations were the Catholic Church and the Orange Order. These groups helped recreate Irish culture on the prairies. They also helped blend people of Irish origin with settlers from other countries. The Irish were therefore a key force for unity in a diverse frontier society. But they also caused major tension with groups who did not share their ideas for how Saskatchewan should develop.

See also

In Spanish: Inmigración irlandesa en Canadá para niños

In Spanish: Inmigración irlandesa en Canadá para niños

- British Canadians

- Canada–Ireland relations

- Irish Montreal before the Great Famine

- List of Ireland-related topics

-

- Irish diaspora

- Irish Americans

- Irish Australians

- Irish (ethnicity)

- Coat of Arms of Canada