Provisional Irish Republican Army campaign facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Provisional IRA campaign |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Troubles | ||||||||

IRA members showing an improvised mortar and an RPG (1992) |

||||||||

|

||||||||

| Belligerents | ||||||||

|

Supported by: |

|

|||||||

| Casualties and losses | ||||||||

| IRA 293 killed over 10,000 imprisoned at different times during the conflict |

British Armed Forces 643–697 killed RUC 270–273 killed |

Loyalist paramilitary groups 28–39 killed | ||||||

| Others killed by IRA 508–644 civilians 1 Irish Army soldier 6 Gardaí 5 other republican paramilitaries |

||||||||

The Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) was a group that used armed force in Northern Ireland and England. From 1969 to 1997, their main goal was to end British rule in Northern Ireland. They wanted to create a united Ireland.

The Provisional IRA started in 1969. It formed after a split in the older Irish Republican Army. This happened partly because the older group was seen as not protecting Catholic areas during the 1969 Northern Ireland riots. The new Provisional IRA became popular by defending these areas in 1970 and 1971.

From 1971 to 1972, the IRA became more active. They launched many attacks against British and Northern Ireland security forces. The British Army called this time the "insurgency phase."

The IRA had short ceasefires in 1972 and 1975. During this time, they discussed their future plans. In the late 1970s, the group changed its structure. It became smaller and used a cell-based system. This made it harder for others to find out about their plans. The IRA then started a longer campaign called the "Long War." Their aim was to make the British government want to leave Ireland. The British Army called this the "terrorist phase."

In the 1980s, the IRA tried to make the conflict bigger. They used weapons given to them by Libya. In the 1990s, they also started bombing economic targets in London and other English cities again.

On August 31, 1994, the IRA announced a ceasefire. They wanted their political party, Sinn Féin, to join the Northern Ireland peace process. The ceasefire ended in February 1996 but started again in July 1997. The IRA agreed to the Good Friday Agreement in 1998. This agreement aimed to end the conflict in Northern Ireland. In 2005, the group officially ended its campaign. Its weapons were taken away under international watch.

Other details about the Provisional IRA's campaign are in these articles:

- For a timeline, see Chronology of Provisional IRA actions

- For information on their weapons, see Provisional IRA arms importation

Contents

- How the IRA Started

- Early Campaign (1970–1972)

- Ceasefires (1972 and 1975)

- Attacks on Civilians and Security Forces

- Attacks Outside Northern Ireland

- IRA Weapons

- Libyan Weapons

- British Special Forces Incidents

- Loyalists and the IRA

- Campaign Before and After the 1994 Ceasefire

- Casualties

- Assessments

- Other Activities

- Images for kids

How the IRA Started

In the early days of the Troubles (1969–72), the Provisional IRA did not have many good weapons. They only had a few old ones left from a previous campaign (1956–1962). The IRA had split in December 1969 into the Provisional IRA and Official IRA groups. For the first two years, the Provisionals mostly defended Irish nationalist areas from attacks.

In 1969, the IRA had not done much during the 1969 Northern Ireland riots. But in the summer of 1970, the Provisional IRA strongly defended nationalist areas in Belfast. They fought against loyalist attackers. During these fights, some Protestant civilians and loyalists were killed. For example, on June 27, 1970, the IRA killed five Protestant civilians in Belfast. Three more were shot in Ardoyne after gun battles during an Orange Order parade.

When loyalists attacked the nationalist area of Short Strand, Billy McKee, an IRA commander, defended St Matthew's Church. This fight, known as the Battle of St Matthew's, lasted five hours. One of his men died, and he was hurt. Three loyalists also died. Many nationalists saw the Provisional IRA as defenders of their people. This helped the group gain a lot of support.

At first, the British Army came to Northern Ireland in August 1969. They were there to help the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) and bring back order. Many Catholics welcomed them, seeing them as neutral. This was different from the RUC and Ulster Special Constabulary, which were mostly Protestant. However, this good relationship did not last.

The Army soon lost trust from many nationalists. This happened after events like the Falls Curfew in July 1970. During this, 3,000 British troops took control of the lower Falls area of west Belfast. After IRA members attacked troops, the British fired many shots. Six civilians were killed in gun battles with both the Official IRA and Provisional IRA. After this, the Provisionals kept targeting British soldiers. The first soldier to die was Robert Curtis in February 1971. He was killed by Billy Reid in a gun battle.

In 1970 and 1971, the Provisional and Official IRAs also fought each other in Belfast. Both groups wanted to be the strongest in nationalist areas.

Early Campaign (1970–1972)

In the early 1970s, the IRA got many modern weapons and explosives. These came mainly from supporters in the Republic of Ireland and Irish diaspora communities. They also got them from the government of Libya.

The conflict grew in the early 1970s. More people joined the IRA. This was because the nationalist community was angry about things like internment (being held without trial) and Bloody Sunday. On Bloody Sunday, British soldiers shot and killed 14 unarmed civil rights marchers in Derry.

The early 1970s were the most intense time for the Provisional IRA. About half of the 650 British soldiers who died in the conflict were killed between 1971 and 1973. In 1972 alone, the IRA killed 100 British soldiers and wounded 500. That same year, they carried out 1,300 bomb attacks. Also, 90 IRA members were killed.

Until 1972, the IRA controlled large parts of Belfast and Derry. But the British Army took these areas back in a big operation called Operation Motorman. After that, strong police and military posts were built in republican areas. In the early 1970s, the IRA often shot at British patrols and fought them in cities. They also killed RUC and Ulster Defence Regiment (UDR) soldiers, both on and off duty. Many civilians were also hurt or killed. The British Army called this time (1970–72) the "insurgency phase."

Another part of their campaign was bombing commercial targets like shops. The IRA's most effective bombing tactic was the car bomb. They packed large amounts of explosives into a car. Then they drove it to the target and blew it up. Seán Mac Stíofáin, an early IRA leader, said car bombs helped tie down British troops. They also made it hard for the British government to run the country. Most of these attacks were not meant to kill people. But they often did kill civilians. For example, the Abercorn Restaurant bombing in Belfast in March 1972 killed two young women and injured 130. The IRA never said they were responsible. The La Mon restaurant bombing in February 1978 killed twelve Protestant civilians.

In rural areas like South Armagh, the IRA used "culvert bombs." These were bombs hidden under drains in country roads. This was so dangerous for British Army patrols that troops had to travel by helicopter. This continued until 2007.

Ceasefires (1972 and 1975)

The Provisional IRA announced two ceasefires in the 1970s. This meant they stopped their armed actions for a while. In 1972, the IRA leaders thought Britain was about to leave Northern Ireland. The British government held secret talks with the IRA leaders. They tried to find a way to stop the fighting. The IRA agreed to a ceasefire from June 26 to July 9.

In July 1972, IRA leaders met with a British team. The IRA wanted Britain to leave by 1975. They also wanted the British Army to go back to barracks and republican prisoners to be freed. The British refused, and the talks ended. On Bloody Friday in July 1972, 22 bombs exploded in Belfast. Nine people died and 130 were injured. The IRA wanted to show their strength. But it was a disaster because the authorities could not handle so many bombs at once.

By the mid-1970s, the IRA leaders realized they would not win quickly. Secret meetings led to another IRA ceasefire from February 1975 to January 1976. Republicans first thought this was the start of Britain leaving. But after a few months, many in the IRA believed the British were just trying to get them into peaceful politics without promises.

Some critics, like Gerry Adams, felt the ceasefire hurt the IRA. They said it led to British spies joining the group. Many members were arrested, and discipline broke down. This led to revenge killings with loyalist groups. The ceasefire ended in January 1976.

The "Long War" (Late 1970s)

From 1976 to 1979, fewer people died in the conflict. This was partly because loyalist violence went down. Also, the IRA changed its tactics after being weakened by the ceasefire. The British focused on gathering information and finding spies. This led to many IRA members being arrested. Between 1976 and 1979, 3,000 people were charged with "terrorist offences." By 1980, there were 800 republican prisoners in Long Kesh prison.

In 1972, there were over 12,000 attacks in Northern Ireland. By 1977, this number dropped to 2,800. In 1976, 297 people died. In the next three years, the numbers were 112, 81, and 113.

After the early years, the IRA used fewer people in its attacks. Instead, smaller, specialized groups carried out ongoing attacks. In 1977, the IRA changed its structure to small, secret cell units. These were harder to find out about. They also started the "Long War" strategy. This meant continuing the armed campaign until the British government got tired of the costs. The British Army called this shift a move from "insurgency" to a "terrorist phase."

The most British soldiers killed in one IRA attack happened on August 27, 1979. This was the Warrenpoint ambush in County Down. Eighteen British soldiers were killed by two culvert bombs. On the same day, the IRA killed Earl Mountbatten. He was killed with two teenagers and another woman by a bomb on his boat in County Sligo. Another IRA tactic from the late 1970s was using homemade mortars. These were fired from trucks at police and army bases.

Attacks on Civilians and Security Forces

The IRA said its campaign was against the British presence in Northern Ireland, not against Protestant or unionist people. However, many unionists believe the IRA's campaign was sectarian (based on religious or group hatred). There are many cases where the IRA targeted Protestant civilians. The 1970s were the most violent years. The IRA also got involved in revenge killings with loyalist groups. This was worst in 1975 and 1976. For example, in September 1975, IRA members shot five Protestants in an Orange Hall. On January 5, 1976, IRA members killed ten Protestant building workers in the Kingsmill massacre.

In similar events, the IRA killed 91 Protestant civilians between 1974 and 1976. The IRA did not officially claim these killings. But they said on January 17, 1976, that they never started sectarian killings. They added that if loyalists stopped their killings, then retaliation would not happen. In late 1976, the IRA and loyalist groups agreed to stop random sectarian killings and car bombings of civilians. Loyalists broke this agreement in 1979 after the IRA killed Lord Mountbatten. But the agreement did stop revenge killings until the late 1980s.

After the British started their "Ulsterisation" policy in the mid-1970s, more IRA victims were RUC and UDR members. Most of these were Protestant and unionist. So, many saw these killings as sectarian attacks. Some historians and politicians have different views on whether the IRA's actions were sectarian or not. Some argue that while the IRA targeted security forces, many of these were Protestant, making the attacks seem sectarian to that community. Others say the IRA's main goal was a united Ireland, not religious hatred.

Towards the end of the Troubles, the IRA also killed people who worked for the RUC and British Army in civilian jobs. These workers were mostly Protestant, but Catholic judges and contractors were also killed. In 1992, an IRA bomb killed eight Protestant building workers near Cookstown. They were working on a British Army base.

Attacks Outside Northern Ireland

England

1970s Attacks

The Provisional IRA was mainly active in Northern Ireland. But from the early 1970s, they also started bombing in England. In June 1972, an IRA leader suggested bombing England to ease pressure on Belfast and Derry. The IRA leadership agreed to this in early 1973, after talks with the British government failed. They believed bombing England would make the British public want their government to leave Northern Ireland.

The first IRA team sent to England had eleven members. They stole cars in Belfast, put explosives in them, and drove them to London. Most of the team were arrested. But two bombs exploded, killing one man and injuring 180 people.

Later, Brian Keenan from Belfast took charge of IRA bombings in England. He directed Peter McMullen to carry out bombings in 1973. A bomb at a barracks in Yorkshire injured a canteen worker. In September 1973, a British soldier died trying to defuse an IRA bomb in Birmingham.

A group of eight IRA members, including the Balcombe Street Gang, carried out some of the most harmful bombings in 1974. They tried to avoid contact with the Irish community in London. They aimed for one attack a week. They also tried to kill people. Ross McWhirter, a politician who offered a reward for finding the bombers, was shot dead. The group also tried to kill Edward Heath. They were arrested after a gun attack on a restaurant. They took two hostages and stayed in a flat for six days in the Balcombe Street Siege. They were sentenced to thirty years each for six murders. They also admitted to the Guildford pub bombings in October 1974, which killed five people. They also bombed a pub in Woolwich, killing two more.

In November 1974, two pubs were bombed in the Birmingham pub bombings. This act, widely blamed on the IRA, killed 21 civilians and injured 162. There were no military targets at these pubs. The Guildford Four and Maguire Seven and the Birmingham Six were jailed for these bombings. But they were later found innocent and released.

1980s Attacks

After the mid-1970s, the IRA did not have a big bombing campaign in England again until the late 1980s and early 1990s. However, they did carry out some major attacks in England during this time.

In October 1981, the IRA bombed Chelsea Barracks. The bomb killed two civilians passing by and injured 40 people, including 23 soldiers. The same month, a British bomb expert was killed trying to defuse an IRA bomb in London.

In 1982, the Hyde Park and Regent's Park bombings killed 11 soldiers. About 50 soldiers and civilians were wounded at two British Army events in London.

In 1984, the IRA tried to kill British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher in the Brighton hotel bombing. She survived, but five people died. Margaret Tebbit, wife of Norman Tebbit, was left permanently disabled.

In 1985, the IRA planned more bombings in London and English seaside towns. They hoped to hurt the tourist industry and launch attacks on military targets. But police arrested Patrick Magee, who was linked to the Brighton bombing, and others in Glasgow. They were sentenced to life in prison.

The Provisional IRA attacked British troops in England several more times. The deadliest was the Deal barracks bombing in 1989. Eleven Royal Marines bandsmen were killed.

Republicans said these bombings made the British government pay more attention. The IRA usually attacked targets only in England. During the IRA's 25-year campaign in England, 115 people died and 2,134 were injured in almost 500 incidents.

Early 1990s Attacks

In the early 1990s, the IRA bombed England more often. They planted 15 bombs in 1990, 36 in 1991, and 57 in 1992. In February 1991, three mortar rounds were fired at the British Prime Minister's office in London. This was a boost for the IRA.

The IRA also launched a very damaging economic bombing campaign in English cities, especially London. This caused huge damage to buildings and businesses. Targets included the City of London, Bishopsgate, and Baltic Exchange. The Bishopsgate bombing caused an estimated £1 billion in damage. The Baltic Exchange bombing caused £800 million in damage. A very sad bombing was the Warrington bomb attack in 1993. It killed two young children, Tim Parry and Johnathan Ball. In March 1994, three mortar attacks at Heathrow Airport in London forced it to close.

Some believe this bombing campaign convinced the British government to talk with Sinn Féin. This happened after the IRA ceasefires in August 1994 and July 1997.

Attacks Elsewhere

The Provisional IRA also carried out attacks in other countries. These included West Germany, Belgium, and the Netherlands, where British soldiers were based. Between 1979 and 1990, eight soldiers and six civilians died in these attacks. This included the British Ambassador to the Netherlands. In May 1988, the IRA killed three RAF men in the Netherlands. On one occasion, the IRA shot two Australian tourists. They said they thought they were off-duty British soldiers. Another time, an IRA gunman killed a German woman. They thought she was a British soldier.

The IRA also sent members to other countries. They went to Europe, Canada, the United States, Australia, Africa, and Latin America. They were there to get weapons, help with logistics, and gather information.

IRA Weapons

In the early 1970s, the IRA took control of most of the weapons left from earlier campaigns. These were mostly old firearms from before World War II. They included rifles, machine guns, and revolvers. In May 1970, some Irish politicians and others were found not guilty of smuggling weapons to the IRA.

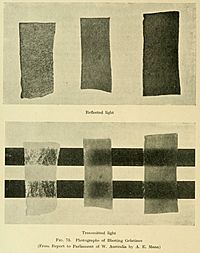

The main source of weapons for the IRA in the Republic of Ireland was explosives. They got gelignite from mines, quarries, farms, and construction sites. One politician said there was "virtually a gelignite trail across the [Irish] border."

When the Irish government started to stop commercial explosives, IRA engineers began making their own. They called these "bomb factories." These made most of the bombs used in Northern Ireland and England. By spring 1972, they made homemade explosives (HMEs) using fertilizers. The British Army thought that by that summer, 90% of bombs came from the South. These early bombs were not always safe. Many IRA members died when bombs exploded too early. So, the IRA made sure their engineers were well trained. A magazine reported that over 48,000 pounds of explosives were used in Northern Ireland in the first six months of 1973.

In the 1980s, homemade explosives from the Republic of Ireland continued to flow into Northern Ireland and England. A 1981 report said that 88.7% of explosives used in Northern Ireland came from the Republic of Ireland. The IRA mostly used fertilizer bombs for its campaign.

Libyan Weapons

In the 1980s, the Provisional IRA got many modern weapons from Muammar Gaddafi's government in Libya. These included heavy machine guns, over 1,000 rifles, hundreds of handguns, rocket-propelled grenades, flamethrowers, surface-to-air missiles, and the plastic explosive Semtex. Four shipments arrived between 1985 and 1986. They brought in 110 tons of weapons. A fifth shipment was stopped by the French Navy in 1987. This showed authorities how powerful the IRA had become. Gaddafi reportedly gave enough weapons to arm two infantry battalions.

So, the IRA was very well armed later in the Troubles. However, most of the damage they caused to the British Army happened in the early 1970s. But they continued to cause many casualties to the British military, RUC, and UDR. According to author Ed Moloney, the IRA had plans to greatly increase the conflict in the late 1980s. They wanted to use the Libyan weapons for this.

The plan was to take and hold areas along the border. This would force the British Army to leave or use extreme force to take them back. This would make the conflict bigger than the British public would accept. But this attack did not happen. IRA sources said that the stopped shipment removed the element of surprise. Spies within the IRA also played a role in the plan's failure. Still, the shipments that got through allowed the IRA to start a strong campaign in the 1980s. The success of the arms smuggling was a defeat for British intelligence. It changed the conflict in Northern Ireland. The Libyan weapons allowed the IRA to fight for a very long time.

However, much of the IRA's new heavy weaponry was rarely used. For example, the surface-to-air missiles (SAMs) and flamethrowers. The SAMs were old models and could not shoot down British helicopters. The missiles became useless when their batteries died. The Semtex plastic explosive was the most useful new weapon for the IRA.

The number of British and Northern Ireland military personnel killed by the IRA increased from 12 in 1986 to 39 in 1988. But it dropped to 27 in 1989 and 18 in 1990. By 1991, the death toll was similar to the mid-1980s, with 14 deaths. Thirty-two RUC members were killed in the same time.

By the late 1980s, the Provisional IRA "could not be beaten," according to journalist Brendan O'Brien. They could be controlled. By the early 1990s, about nine out of ten IRA attacks failed to cause casualties. Republican sources said that by the early 1990s, the IRA could not achieve their goals only through military means.

British Special Forces Incidents

The IRA suffered many losses from British special forces like the Special Air Service (SAS). The biggest loss was in the Loughgall Ambush in 1987. Eight IRA members were killed while trying to destroy a police station. The East Tyrone Brigade was hit hard. Twenty-eight of its members were killed by British forces between 1987 and 1992. In many cases, IRA members were killed in ambushes by British special forces. Some people said this was a campaign of assassination by state forces.

Another major event happened in Gibraltar in March 1988. Three unarmed IRA members were shot dead by an SAS unit while looking for a bombing target. This was called Operation Flavius. Later, at the funerals of these IRA members in Belfast, a loyalist gunman attacked. At a funeral for one of his victims, two British Army corporals were taken, beaten, and shot dead by the IRA. This happened after they drove into the funeral procession. This is known as the Corporals killings.

However, some undercover operations failed. For example, a shoot-out happened in Cappagh in March 1990. Undercover security forces were ambushed by an IRA unit. Two months later, Operation Conservation was stopped by the IRA's South Armagh Brigade. A British soldier in an undercover position was shot dead. In May 1980, four IRA members were arrested after being surrounded by the SAS in Belfast. An SAS commander was killed.

Loyalists and the IRA

From the late 1980s, loyalist groups started killing IRA and Sinn Féin members. These attacks killed about 12 IRA and 15 Sinn Féin members between 1987 and 1994. This was unusual because most loyalist victims were Catholic civilians. Loyalists also killed family members of known republicans. Recently released documents show that British military intelligence knew that some soldiers in the Ulster Defence Regiment (UDR) were also loyalist paramilitaries. Despite this, the British government increased the UDR's role in Northern Ireland.

Documents from May 2006 show that loyalist groups and British Army units like the UDR had members who belonged to both. A report from 1973 said that 5–15% of UDR soldiers were linked to loyalist groups. It was believed that the UDR was the main source of weapons for Protestant extremist groups. The British government knew that UDR weapons were used to kill Catholics.

Loyalists got help from parts of the security forces, including the British Army and RUC Special Branch. Loyalist sources have said they received information about republicans from British Army and police intelligence. A British Army agent within the Ulster Defence Association (UDA), Brian Nelson, was found guilty in 1992 of killing Catholic civilians. It was later found that Nelson also helped bring weapons for loyalists from South Africa in 1988.

In 1993, loyalist groups killed more people than republican groups for the first time since the 1960s. In 1994, loyalists killed eleven more people than republicans. In 1995, they killed twelve more. In 1995, the Provisional IRA's ceasefire was still in place.

In response, the IRA started killing leading members of the UDA and UVF. By the late 1980s, the IRA leadership would not approve attacks on Protestant areas that would likely kill civilians. They only targeted specific loyalist leaders. This was because killing civilians hurt the republican movement's public support. The IRA said in 1986 that they would not kill ordinary Protestants. But they would act against those who tried to scare their people into accepting British rule. Gerry Adams said in 1989 that Sinn Féin did not approve of the deaths of non-fighters.

To make their actions more effective, the IRA targeted senior loyalist paramilitary figures. Among those killed were John McMichael, Joe Bratty, Raymond Elder, and Ray Smallwoods of the UDA. Also, John Bingham and Robert Seymour of the UVF.

One IRA bomb on October 23, 1993, caused civilian deaths. A bomb was placed at a fish shop on Shankill Road. It was meant to kill the UDA's senior leaders, who sometimes met above the shop. Instead, the bomb killed eight Protestant civilians, a low-level UDA member, and one of the bombers. Fifty-eight more people were injured. This led to revenge killings by the UVF and UDA against Catholic civilians.

According to the Conflict Archive on the Internet (CAIN), the Provisional IRA killed 30 loyalist paramilitaries in total. Lost Lives says the number is 28.

Campaign Before and After the 1994 Ceasefire

Early 1990s

By the early 1990s, the death toll had dropped a lot from the 1970s. But the IRA campaign still greatly disrupted daily life in Northern Ireland.

- In 1987, the IRA carried out almost 300 attacks. They killed 31 RUC, UDR, and British Army personnel. They also killed 20 civilians.

- In 1990, IRA attacks killed 30 soldiers and RUC members.

- In 1992, the IRA carried out 426 attacks.

The IRA could continue its violence for a long time. The British government's goal in the 1980s was to destroy the IRA, not to find a political solution. The conflict also cost a lot of money. The UK had to spend a huge amount to keep its security system running in Northern Ireland.

From 1985 onwards, the IRA attacked RUC and Army bases for five years. They destroyed 33 British security buildings and badly damaged nearly a hundred. The attacks forced the UK government to close some bases. The British Army in the region grew from 9,000 men in 1985 to 10,500 by 1992. This was after the IRA increased its mortar attacks.

In South Armagh, IRA activity increased in the early 1990s. Traveling by road became so dangerous for the British Army that they used helicopters to move troops and supplies. This continued until the late 1990s. The IRA shot down five helicopters and damaged at least three more. They used heavy machine guns and homemade mortars.

The IRA also used high-velocity sniper rifles. Two sniper teams in South Armagh killed nine security force members this way. To avoid problems with remote detonators, the IRA used radar beacons to set off their bombs. By 1992, the IRA's use of long-range weapons forced the British Army to build checkpoints further from the border.

Another IRA tactic was the "proxy bomb." This happened several times between October 1990 and late 1991. A victim was kidnapped and forced to drive a car bomb to its target. In the first attacks in October 1990, all three victims were Catholic men who worked for the security forces. Their families were held hostage to make sure they followed orders. The first victim died with six soldiers. The second escaped, but a soldier was killed. The third attack caused no casualties. Proxy bomb attacks continued for months. Very large bombs were used. This tactic was stopped because it caused strong negative feelings among nationalists.

In the early 1990s, the IRA increased its attacks on commercial targets in Northern Ireland. For example, in May 1993, the IRA set off car bombs in Belfast, Portadown, and Magherafelt. This caused millions of pounds in damage. In January 1994, the IRA planted eleven firebombs in shops in Belfast. This also caused millions in damage. In 1991, the IRA used 142 incendiary devices against shops and warehouses.

The Ceasefires

In August 1994, the Provisional IRA announced a "complete stop to military operations." This was the result of years of talks between republican leaders, the Irish government, and the British government. They realized that neither side could win the conflict by force. They thought they could achieve more through talks.

Many Provisional IRA members were reportedly unhappy that the armed struggle ended without a united Ireland. However, the peace strategy has led to big political gains for Sinn Féin. It can be argued that Sinn Féin is now the most important part of the republican movement. The 1994 ceasefire, while not a final end to IRA actions, marked the end of its full armed campaign.

The Provisional IRA ended its 1994 ceasefire on February 9, 1996. They were not happy with the peace talks. They showed this by setting off a truck bomb at Canary Wharf in London. This killed two civilians and caused huge damage. In the summer of 1996, another truck bomb damaged Manchester city centre. However, the IRA campaign after the ceasefire was not as intense as before. In 1996–1997, the IRA killed 2 British soldiers, 2 RUC officers, 2 British civilians, and 1 Irish police officer. They started their ceasefire again on July 19, 1997.

Many believed these IRA actions in 1996–97 were used to gain power in talks with the British government. In 1994–95, the British government had refused to talk with Sinn Féin until the IRA gave up its weapons. But by 1997, the new government was ready to include Sinn Féin in peace talks before the IRA gave up weapons. This condition was officially removed in June 1997.

Another idea is that the IRA leadership allowed some violence to avoid a split between hardliners and moderates. But they always stressed the need for a second ceasefire. Once they had convinced or removed the hardliners, they restarted the ceasefire.

Casualties

According to the Conflict Archive on the Internet (CAIN), the IRA was responsible for 1,705 deaths. This is about 48% of all deaths in the conflict. Of these:

- 1,009 (59.2%) were members or former members of British security forces. This includes 697 British military personnel and 312 British law enforcement personnel (RUC, prison officers, English police).

- 508 (29%) were civilians.

- 133 (7.8%) were IRA members. They were killed as informers or in accidental bomb explosions.

- 39 (2.2%) were loyalist paramilitary members.

- 8 (0.4%) were members of Irish security forces (Gardaí, Irish Army).

- 5 (0.2%) were members of other republican paramilitary groups.

Another study, Lost Lives, says the Provisional IRA caused 1,781 deaths up to 2004. Of these:

- 944 (53%) were British security forces.

- 644 (36%) were civilians.

- 163 (9%) were Republican paramilitary members (including IRA members who died in bomb accidents).

- 28 (1.5%) were loyalist paramilitary members.

- 7 (0.3%) were Irish security forces.

Lost Lives states that 294 Provisional IRA members died in the Troubles. CAIN says 276 IRA members died. Also, some Sinn Féin activists or councillors were killed.

About 120 Provisional IRA members died by accident. Most were killed by their own explosives. Nine IRA members died on hunger strike. Of the other IRA deaths, about 150 were killed by the British Army. The rest were killed by loyalist groups, the RUC, and the UDR.

Many more IRA volunteers were imprisoned than killed. Journalists estimate that between 8,000 and 10,000 Provisional IRA members were imprisoned during the conflict.

Assessments

British Army Report

A British Army document from 2007 said that the British Army failed to defeat the IRA by force. But it also said they "showed the IRA that it could not achieve its ends through violence." The report looked at 37 years of British troop deployment. It was made by three officers in 2006. The report called the IRA "professional, dedicated, highly skilled and resilient."

The report divides IRA activity into two main periods. The "insurgency" phase (1971–1972) and the "terrorist" phase (1972–1997). The British Army says it stopped the IRA insurgency by 1972. But IRA members escaped to the Republic of Ireland. From there, they continued cross-border attacks. The IRA then became a cell-structured group. The report also says that British efforts in the 1980s aimed to destroy the IRA, not to negotiate. It concludes that the British campaign did not result in a clear victory.

Other Views

Some authors also concluded that the Provisional IRA was not defeated. They say it was a bloody stalemate where neither side could destroy the other. According to Brendan O'Brien, the IRA "could end its armed campaign from a position of strength." Political experts say that while the IRA did not achieve a united Ireland, their campaign was made legitimate by the peace process and the Good Friday Agreement.

Other Activities

Besides fighting, the Provisional IRA did other things. These included "policing" nationalist communities, robberies, and kidnappings for money. They also raised money in other countries, took part in community events, and gathered information. The Independent Monitoring Commission (IMC), which watches paramilitary groups, says the Provisional IRA has stopped all these activities.

Paramilitary Policing

The Provisional IRA often punished actions that the community also thought were wrong. Punishments ranged from warnings to physical attacks, gunshots, or forcing someone to leave Ireland. This was often called "summary justice" by the media. The IRA usually said they investigated fully before punishing someone. This process had different levels of severity. For a small thief, it might start with a warning. Then it could be a "punishment beating" with bats. If the behavior continued, a "knee-capping" (gunshot wounds to limbs) might happen. The final step was a death threat if the person did not leave Ireland. The IMC says the Provisional IRA has been asked to restart this policing but has refused.

Suspected informers (spies) were handled by a special unit. This unit would kidnap and question suspects. They sometimes used harsh methods to get confessions. These confessions were sometimes recorded. A secret board would then decide the punishment, often death by gunshot. The IRA sometimes announced these deaths. The bodies of killed informers were usually found in isolated areas. Sometimes, recordings of their confessions were released.

This kind of justice was often based on weak evidence. It was carried out by untrained people. This led to what the Provisional IRA has called terrible mistakes. As of February 2007, the IMC says the Provisional IRA has told members not to use physical force. They also noted that the leadership strongly opposes members being involved in crime.

Internal Republican Conflicts

The Provisional IRA also targeted other republican groups and its own members who did not follow orders. In 1972, 1975, and 1977, the Official IRA and Provisional IRA attacked each other. Several people died on both sides. The last known example of this was in 2000. An IRA member was shot for opposing the Provisionals' ceasefire.

Activities in Republic of Ireland

The Provisional IRA's rules forbid military action against the Republic of Ireland's forces. However, members of the Garda Síochána (Ireland's police force) have been killed. This includes Detective Garda Jerry McCabe. McCabe was killed by machine-gun fire in 1996 during a post office delivery escort. Sinn Féin has asked for his killers to be released under the Good Friday Agreement. In total, the Provisional IRA killed six Gardaí and one Irish Army soldier. Most of these deaths happened during robberies.

Images for kids

| Chris Smalls |

| Fred Hampton |

| Ralph Abernathy |