Society of United Irishmen facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Society of United Irishmen

Cumann na nÉireannach Aontaithe

|

|

|---|---|

| Founded | 1791 |

| Dissolved | 1804 |

| Newspaper | Belfast: Northern Star. Cork: Harp of Erin. Dublin: The Rights of Irishmen, or National Evening Star; Union Star; Press. Roscrea: Southern Star. |

| Ideology | Rights of Man Representative government National independence |

| International affiliation | Allied to the French First Republic, United Scotsmen, United Englishmen/United Britons |

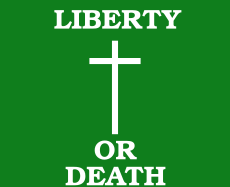

| Party flag | |

|

|

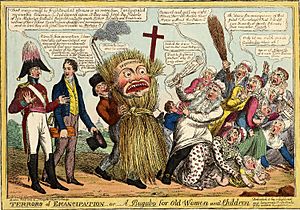

The Society of United Irishmen was a group formed in Ireland in 1791, inspired by the French Revolution. Their main goal was to achieve "equal representation of all the people" in the Irish government. When peaceful changes didn't work, and facing opposition from the British government and religious divisions in Ireland, the United Irishmen started a major rebellion in 1798.

After the rebellion was put down, the Irish Parliament in Dublin was closed. Ireland then became part of a new country called the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, joining with Great Britain. Later, in 1803, there was another attempt to restart the movement and rebellion in Dublin, but it failed.

The United Irishmen believed in ideas like those from the American Revolution and the French Declaration of the Rights of Man. The first group was formed by Presbyterian business people in Belfast in 1791. They promised to work together with the mostly Catholic people of Ireland. Their plan was to end the "Protestant Ascendancy" (where Protestants had most of the power) and create a government that truly represented everyone.

As the Society grew in Belfast, Dublin, and other parts of Ireland, many ordinary people joined. This included workers and farmers who were already organized in their own groups. The goals of the movement became even stronger: they wanted Catholic emancipation (full rights for Catholics) and universal manhood suffrage (the right for every man to vote). They also wanted Ireland to become a republic, separate from Britain. They even planned a rebellion with help from France and new groups in Scotland and England. However, government spies and arrests disrupted their plans. So, when the rebellion happened in 1798, it was a series of smaller, uncoordinated uprisings.

The British government used the rebellion as a reason to unite Ireland and Great Britain. In 1800, the Irish Parliament was abolished. Ireland then sent representatives to the Parliament in Westminster, London. Later attempts to revive the United Irishmen movement, like Robert Emmet's rising in Dublin in 1803, failed.

Since 1898, people in Ireland have debated the legacy of the United Irishmen. Both Irish nationalists and Ulster unionists have different views on what the Society truly stood for.

Contents

Why the Society Started

Early Dissenters: "Americans in Their Hearts"

The Society of United Irishmen began at a meeting in a Belfast pub in October 1791. Most of the people there were Presbyterians. They wanted to change the government of Ireland to have "civil, political and religious liberty." Presbyterians were "Dissenters," meaning they weren't part of the official Anglican Church (the Church of Ireland). They faced some of the same unfair rules as the Catholic majority, like not being able to hold certain jobs or vote.

The Irish Parliament in Dublin didn't offer much chance for Presbyterians to be heard. Many areas were controlled by wealthy lords, not by the people. For example, Belfast's representatives were chosen by a small group of people connected to powerful families. The Parliament also had little power over the "Dublin Castle administration," which was controlled by the King's ministers in London. The Belfast group felt that Ireland had "no national government" and was ruled by "Englishmen."

Because of these problems, many Presbyterians were leaving Ireland for the North American colonies. From 1710 to 1775, over 200,000 sailed to America. When the American Revolutionary War began in 1775, many Presbyterian families had relatives fighting against the British.

Many of the Society's founders were members of Belfast's Presbyterian churches. Leaders like William Drennan, Samuel Neilson, and Henry Joy McCracken came from these churches. Their ministers often taught about the right to resist unfair government. One minister even preached in his military uniform! The British Viceroy (a high-ranking official) described Ulster Presbyterians as "Americans in their hearts" because of their desire for freedom.

The Volunteers and Patriot Leaders

The first members of the Society were also connected to the Irish Volunteers. These groups were formed to protect Ireland when British soldiers were sent to fight in America. While some Volunteer companies were just local landlords and their armed servants, in Dublin and especially in Ulster, they brought together many Protestants.

In 1782, with Volunteers surrounding the Parliament in Dublin, Henry Grattan, a leader of the "Patriot" group, pushed for Irish rights. London agreed, giving Ireland more power to make its own laws. In 1783, Volunteers again gathered in Dublin. This time they wanted to get rid of "rotten boroughs" (areas with few voters but a lot of power) and expand voting rights for Protestants. But the British could now send more troops to Ireland, and the Parliament refused to be pressured.

After this, in 1784, disappointed Volunteers in Ulster began to include Catholics in their ranks, forming "united" companies. They believed that "a general Union of all the inhabitants of Ireland is necessary." In Belfast, Volunteer companies even paraded outside the first Catholic church to show their support.

News of the French Revolution in 1789 brought new hope for change. France's Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen seemed to show that even a Catholic country could have a revolution for liberty. Thomas Paine's book, Rights of Man, which supported the French Revolution, was very popular in Belfast. The new Society of United Irishmen distributed thousands of copies.

On July 14th, the anniversary of the Fall of the Bastille (a French prison), Belfast celebrated with a parade. They declared their support for the French people and wished for "all Civil and Religious Intolerance annihilated in this land."

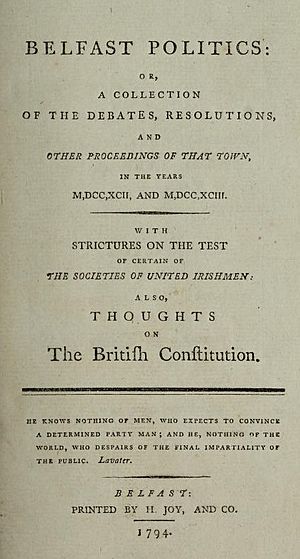

Belfast Discussions

First Goals

Amidst this excitement about France, William Drennan suggested a "benevolent conspiracy" for the people. Its goal was "Real Independence to Ireland, and Republicanism." When Drennan's friends met in Belfast, they decided:

- That British influence in Ireland was too strong and needed a "cordial union" among all Irish people.

- That the only way to fight this influence was through a "complete and radical reform" of how people were represented in Parliament.

The "conspiracy," which Theobald Wolfe Tone suggested calling the Society of the United Irishmen, went beyond earlier Protestant demands. They wanted to limit British power through a Parliament where "all the people" would have "equal representation." However, it wasn't clear if Catholics would get full rights immediately. Tone noticed that many people agreed with Catholic rights in principle but wanted to delay them.

The Catholic Question

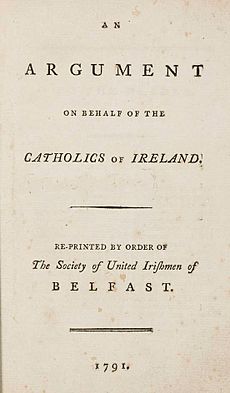

Thomas Russell invited Tone to the Belfast meeting because Tone had written An Argument on behalf of the Catholics of Ireland. Tone believed that Ireland couldn't have a truly representative government until Protestants and Catholics worked together. He argued that denying Catholics rights was unfair. He pointed to America and France, where Catholics and Protestants had equal rights. He also mentioned the Polish Constitution, which promised friendship between Catholics, Protestants, and Jews.

Tone warned that if Irish Protestants remained "illiberal" (narrow-minded), Ireland would continue to be ruled only for the benefit of England and the wealthy Protestant elite. The Belfast Catholic Society supported Tone's argument, stating their desire to be part of the government and denying any wish to reclaim lost lands.

On Bastille Day in 1792, the United Irishmen in Belfast made their position clear. Some, like William Bruce, suggested a slow, step-by-step approach to Catholic rights. But Samuel Neilson argued that the only question was "whether Irishmen should be free." The idea of delaying Catholic rights was defeated.

However, this debate showed a growing split. While Belfast and some Protestant areas supported Catholic rights, many Protestants in other parts of Ireland were not easily convinced. The Armagh Volunteers, for example, boycotted a meeting in 1793. They were already moving towards forming the loyalist Orange Order in 1795, fighting Catholic "Defenders" over land and jobs.

Equal Representation

In 1793, the government itself allowed some changes. The "Catholic Relief Act" gave Catholics the right to vote, though not yet to be in Parliament. This pleased some Catholics but worried Protestant reformers. They feared that further changes to voting rules would lead to a Catholic majority.

Tone and Russell felt that the Society's original pledge for "impartial and adequate representation" was too vague. Within two years, they and other leaders agreed on much bigger changes. By November 1793, they called for:

- Equal voting districts.

- Parliaments held every year.

- Paid representatives.

- Universal manhood suffrage (every man having the right to vote).

This meant that wealth or religion should not stop someone from having political rights. This new democratic plan fit with the Society becoming a large popular movement. Many artisans, shopkeepers, and farmers joined. In Belfast and Dublin, some of these new members had already formed their own democratic clubs.

In 1795, when a new Lord Lieutenant (the British ruler in Ireland) who supported Catholic rights was suddenly removed, even more ordinary people joined the United Irish societies. They believed that Ireland's "much boasted constitution" didn't truly exist. They urged people in Ireland, England, and Scotland to push for "radical and complete Parliamentary reform" through national meetings. In May, delegates in Belfast representing 72 societies changed the Society's pledge. It now promised "an equal, full and adequate representation of all the people of Ireland," and removed any mention of the existing Irish Parliament.

This radical thinking followed a rise in trade union activity. The Northern Star newspaper reported a "bold and daring spirit of combination" among workers. While some United Irish leaders, like Samuel Neilson, wanted to stop these worker groups, others, like Thomas Russell and James Hope, understood the real problems of the working class.

In 1794, Dublin United Irishmen argued that the "scattered labour of the lowest ranks" should be represented as much as the "fixed and solid property" that controlled Parliament. They appealed directly to "the poorer classes of the community," promising that their burdens could be eased by giving them a fair say in lawmaking.

However, the United Irishmen as a group didn't offer specific plans for economic or social changes. They focused on what everyone agreed on: political reform. One big missing piece was a plan for land reform, which was a huge issue for most Irish farmers.

Women's Role

The United Irishmen was mainly a group for men, like other societies of the time. While their newspaper, the Northern Star, praised the idea of men and women learning from each other and reviewed Mary Wollstonecraft's Vindication of the Rights of Woman, they didn't call for women to have political rights. The newspaper focused only on women's education.

Some critics argued that the United Irishmen's promise of "impartial representation" should include women. William Drennan himself admitted he saw no good argument against women voting, but he thought it would take generations for society to accept it.

However, women like Drennan's sister Martha McTier and McCracken's sister Mary-Ann, and Emmet's sister Mary Anne Holmes, read Wollstonecraft's work. They believed women should reject their "dependent situation" and gain liberty.

Women did form their own groups within the movement. In 1796, the Northern Star published a letter from the "Society of United Irishwomen," blaming the English for the violence of the revolutions. Jane Greg was described as "very active" in leading these "Female Societies." However, Mary Ann McCracken felt that women with "rational ideas of liberty and equality" shouldn't have separate organizations, as it might mean keeping women "in the dark."

Before the rebellion, the Dublin society's newspaper, The Press, published appeals to Irish women to get involved in politics. Some women, like Henrietta Battier and Margaret King, joined the Society after these appeals.

Letters from Martha McTier and Mary Ann McCracken show that women were important as trusted friends, advisors, and messengers. Informers reported that by 1797, "women are equally sworn with men," suggesting some women were taking risks and joining the secret organization. Middle-class women, like Mary Moore, were active in Dublin.

There are fewer records about the role of peasant and working women. But during the 1798 uprising, they helped in many ways, some even fighting, as remembered in ballads like Betsy Gray. British troops treated women, young and old, with great cruelty during the rebellion.

Growth and Radical Changes

Jacobins, Masons, and Covenanters

A French visitor to Ireland in 1796-97 was surprised to hear a young worker talking about "equality, fraternity, and oppression" and "reform of Parliament." This showed how revolutionary ideas were spreading even to rural areas. Thomas Russell was one of the key figures who traveled around, recruiting for the Society.

When recruiting in north Down and Antrim, Jemmy Hope appealed to the "republican spirit" of the Presbyterian community. Many Presbyterian ministers and elders, especially those who followed the Scottish Covenanting tradition (who believed in "no king but Jesus"), became involved in the rebellion. Some even preached about the "immediate destruction of the British monarchy."

The United Irishmen also found allies in masonic lodges. Even though Masons usually avoided politics, their lodges were places where political ideas were discussed. As the United Irishmen became more secret, Masonic lodges became a cover for their activities. William Drennan had always imagined his "conspiracy" would have "much of the secrecy and somewhat of the ceremonial of Free-Masonry."

The New System

In 1793, Britain went to war with France. This caused more tension in Belfast. British soldiers attacked the town, supposedly because pubs displayed pictures of French revolutionary figures. They also attacked the homes of people connected to the Northern Star newspaper, which was eventually shut down in 1797. New laws banned political meetings and replaced the Volunteers with a paid militia and local armed groups called Yeomanry. In May 1794, the Society itself was outlawed.

Towards the end of 1794, United Irish leaders in Belfast created a "new system" for their organization. This system aimed to combine democratic ideas with the need for a secret, coordinated group. Local societies were to be small (7 to 35 members) and would split and multiply as they grew. Delegates from these societies would then choose a "provincial directory" of five members. This directory could make its own decisions to keep things secret.

In June 1795, four leaders from Ulster—Neilson, Russell, McCracken, and Robert Simms—met with Tone. They swore an oath on Cave Hill "never to desist in our efforts until we had subverted the authority of England over our country, and asserted our independence." In the following months, while Tone went to France to seek help, they created a secret military organization. Each local society would train a company of soldiers, and these companies would form battalions and regiments.

Alliance with Catholic Defenders

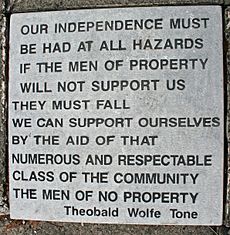

By March 1796, Tone understood that if wealthy people wouldn't support them, the United Irishmen would rely on "that numerous and respectable class of the community, the men of no property." The largest group of such people were the Defenders. They were a secret Catholic group that formed in response to attacks on Catholic homes. By the early 1790s, the Defenders were active across Ulster and the Irish midlands. They talked about getting rid of unfair taxes and rents, and hoped for a French invasion to reclaim Protestant lands.

Defenders and United Irishmen began to work together. Religion wasn't a barrier to joining the Defenders. In Dublin, many Protestants joined the Defenders to work for a common cause. In early 1796, Dublin Defenders sent a group to Belfast to unite the two movements, which had been separate.

However, the Defenders' oaths and beliefs sometimes mixed Catholic religious ideas with revolutionary goals. Many Defenders saw the French as fellow Catholics fighting Protestants, even though the French Republic was anti-clerical. While leaders like Hope and McCracken tried to bridge the gap, the Belfast leaders chose Catholic members to be their messengers to the Defenders.

The Teeling brothers, sons of a wealthy Catholic linen maker, seemed to have control over the Defenders in Down, Antrim, and Armagh. The United Irishmen helped Catholics who were victims of violence, sheltering them on Presbyterian farms. This built trust and helped bring Defenders into the republican movement. The United Irishmen convinced Defenders of the need for Ireland's independence from England.

What really brought them together was the promise of practical benefits. A British general reported that local republicans had to offer "the Abolition of Titles, Reduction of Rents etc." to motivate "the lower orders of Roman Catholics."

Dublin and the Catholic Committee

The Dublin branch of the Society, which Tone helped start in 1791, initially stayed separate from the more radical groups in the city. They also didn't immediately adopt the "New System" used in Ulster. While Belfast had many small societies, Dublin, with a much larger population, kept one large society.

From the start, the Dublin group included members of the "new race of Catholics," like wealthy merchants and professionals. Many were prominent members of the Catholic Committee, including its chairman, John Keogh. In 1793, Keogh, with Tone as his secretary, met with the King in London. This led to the Catholic Relief Act, which gave Catholics the right to vote. Because of this success, many were hesitant to abandon legal, constitutional methods.

However, in January 1794, Samuel Neilson urged the Dublin society to reorganize like the Ulster model, as there were spies among them. The idea of meeting in secret was rejected at first, as they wanted to remain a legal reform movement.

A shift happened when Keogh replaced his secretary, Richard Burke, with Tone, a known democrat. The British Prime Minister, Pitt, was already considering uniting Ireland and Great Britain, which would allow Catholics into Parliament but as a minority in a larger kingdom. This prospect was uncertain, and Catholics were becoming desperate for political equality.

Drennan, however, was suspicious of Catholic intentions, fearing they only cared about their own rights, not full independence or democratic reform. He also worried about the French Republic's anti-clericalism. Until his trial in May 1794, Drennan promoted a "Protestant but National" inner society in Dublin.

Things came to a head in April 1794 with the arrest of Reverend William Jackson, a French agent who had met with Tone. Tone was allowed to go into exile in America, while Archibald Hamilton Rowan fled. This scandal led Thomas Troy, the Catholic Archbishop of Dublin, to warn against French ideas and threaten any Catholic joining the United Irishmen with excommunication (being expelled from the Church). Hopes for open political action were crushed in March 1795 when the new Lord Lieutenant, William Fitzwilliam, who supported Catholic admission to Parliament, was suddenly recalled.

Encouraged by northern leaders like Neilson, Russell, and Hope, members of the Dublin society regrouped with previously ignored radical groups and Defenders. They used various secret organizations as a cover to spread the movement into the provinces. This led to a mass organization, very different from the original society. By May 1798, the new United Irish coalition claimed about 10,000 members in Dublin and another 9,000 in Dublin county.

Mobilization and Repression

On December 15, 1796, Tone arrived off Bantry Bay with a French fleet carrying about 14,450 soldiers. However, a storm prevented them from landing. The unexpected death of the French commander, Lazare Hoche, was a major setback. His rival, Napoleon, later sailed for Egypt in 1798 with the forces that could have helped Ireland.

Still, the Bantry Bay attempt showed that French help was possible and that British forces were unprepared. At the same time, the government stopped all attempts at peaceful political discussion. In April 1797, William Orr was charged under the Insurrection Act for giving the United Irish oath to soldiers. He became the movement's first famous martyr and was executed in October.

Orr's arrest marked the start of General Lake's harsh crackdown in Ulster. People showed support for those arrested. When Orr was detained, hundreds of his neighbors harvested his crops. When Neilson was arrested, 1,500 people dug his potatoes in seven minutes. These "hasty diggings" often turned into military drills, with men marching with their spades. In May 1797, Yeomanry attacked one such gathering, killing eleven people.

General Lake, known for his brutal interrogation methods, then focused on disarming Leinster and Munster. After Bantry Bay, societies in the south also saw a flood of new members. In Leinster, the "new system" took hold, with various republican clubs and Defender groups organized under a provincial executive in Dublin. Key members included Thomas Addis Emmet, Richard McCormick, the Sheares brothers, and Lord Edward Fitzgerald.

"Unionizing" in Britain

United Scotsmen

The war with France was also used to crush reformers in Great Britain. In 1793, Thomas Muir and others were sent to Australia for their reform efforts. The judge highlighted Muir's connection to the "ferocious" Archibald Hamilton Rowan and the United Irish papers found with him.

In England, the 1794 Treason Trials and later laws like the Treason Act and Seditious Meetings Act targeted groups like the London Corresponding Society. United Irishmen like Roger O'Connor and Jane Greg had been working to gain support for the Irish cause among these groups.

Facing this repression, some democratic movements in Scotland and England began to think that force was necessary to achieve universal voting rights and annual parliaments. Visits by United Irishmen in 1796-97 and a growing number of Irish migrants helped spread these ideas and encourage the formation of new societies based on the Irish model.

When authorities first learned about the United Scotsmen in 1797, they saw it as a Scottish branch of the United Irishmen. Their rules were almost identical to those of the United Irishmen. At their peak, the United Scotsmen had over 10,000 members, mostly artisans and weavers.

United Englishmen, United Britons

With encouragement from Irish and Scottish visitors, the first groups of United Englishmen formed in northern England in late 1796. Their secret meetings, oath-taking, and support for force mirrored their Irish inspirations. They followed the Ulster system of small, local groups.

A Catholic priest, James Coigly, who had been involved in organizing during the Armagh disturbances, worked from Manchester to spread the United system to other English towns. In London, Coigly met with Irishmen who had influenced the radical London Corresponding Society. They held meetings where delegates from London, Scotland, and other regions agreed "to overthrow the present Government, and to join the French as soon as they made a landing in England."

The "United Britons" resolution was discussed by Irish leaders in Dublin in July 1797. This idea that "England, Scotland and Ireland are all one people acting for one common cause" made some militants believe they could win freedom even without French help.

In February 1798, Coigly was arrested while trying to deliver a message to the French government from the United Britons. Although the idea of a mass movement ready for rebellion in Britain was probably exaggerated, it was enough proof to justify a French invasion. The United movement in Britain was broken up by arrests, and Coigly was executed.

Authorities were quick to blame English radicals and the large number of Irish sailors for the Spithead and Nore mutinies in April and May 1797. They claimed the United Irishmen were behind the Nore mutineers' decision to hand the fleet over to the French. Much was made of Valentine Joyce, a leader at Spithead, who was described as a "seditious Belfast clubist."

However, whether this Valentine Joyce was truly Irish and a republican is debated. While the Northern Star newspaper may have circulated among the mutineers, there's no clear evidence of a United Irish plot to take over the fleet. In Ireland, there was talk of seizing British warships during a general uprising, but it was only after the Spithead and Nore mutinies that the United Irishmen realized they could spread their ideas within the Royal Navy.

Several mutinies caused by Irish sailors occurred in 1798. On HMS Defiance, a court martial found evidence of oaths to the United Irishmen and sentenced eleven men to hang.

The 1798 Rebellion

The Call from Dublin

The United Irishmen never fully achieved the national leadership they planned. Their leaders were split between Ulster and Leinster. In June 1797, they met in Dublin to discuss demands for an immediate uprising from the north. The meeting ended in chaos, and many Ulster delegates fled to avoid arrest. In the north, the United societies hadn't recovered from the arrests of key leaders like Neilson, Russell, Charles Teeling, McCracken, and Simms in September. These arrests left the Belfast leadership open to less trustworthy people, including government spies.

The initiative then passed to the Leinster leaders. Their organization was too weak in the summer of 1797 to act immediately. But in the winter of 1797–98, it grew stronger in areas like Dublin, Kildare, and Meath, and spread to the midlands and southeast. In February 1798, Lord Edward Fitzgerald estimated that there were 269,896 United Irishmen nationwide. However, it's not certain how many would actually fight, especially without French help. Most only had simple pikes.

In March 1798, almost the entire Leinster committee was arrested, along with two directors, William James MacNeven and Thomas Addis Emmet, and all their papers. Facing the collapse of their system, Fitzgerald, along with Neilson (who had been released from prison due to illness) and the Sheares brothers, decided on a general uprising for May 23rd. The plan was for the United army in Dublin to seize important points in the city, while armies in surrounding counties would surround the city and advance into its center. Once mail coaches from the capital were stopped, it would signal the rest of the country to rise.

On the planned day, the signal was given, but the uprising in Dublin failed. The Yeomanry had been warned. Fitzgerald was fatally wounded on May 19th, and on the morning of the 23rd, Neilson, who was crucial to the planning, was captured. Tens of thousands of people did rise up across the country, but it turned into a series of uncoordinated local uprisings.

The South

Some historians believe that the biggest uprisings in 1798, like the one in Wexford, were connected to the United Irishmen more by chance than by shared goals. Daniel O'Connell, who hated the rebellion, even suggested there were no United Irishmen in Wexford.

The Wexford Rebellion started not in the Catholic south of the county, where there was more political organization, but in the religiously divided north and center. The arrival of the brutal North Cork Militia on May 26, 1798, is seen as the trigger.

The rebels swept south through Wexford Town, facing their first defeat at New Ross on May 30th. This was followed by the terrible massacre of loyalist prisoners at Scullabogue and, later, at Wexford Bridge. While some historians note similarities to massacres in Paris and that some Catholics were killed and Protestants were among the rebels, loyalists saw these events as purely sectarian. This was used effectively in the north to make people abandon the republican cause. The fact that a Catholic priest, Father John Murphy, led the rebels in their first victory at Oulart Hill was also emphasized.

After a major defeat of over 20,000 rebels at Vinegar Hill on June 21st, remnants of the "Republic of Wexford" marched north. But few joined them. Those in the region who had risen on May 23rd had already been scattered. On July 20th, the remaining Wexford men surrendered. Most benefited from an amnesty offered by the new Lord Lieutenant, Charles Cornwallis, to end the resistance. This law was pushed through the Irish Parliament by Lord Clare, who wanted to separate Catholics from the "Godless Jacobinism" (radical French ideas).

Wexford remained under military rule until 1806 due to ongoing rebel groups. Michael Dwyer continued a guerrilla resistance in the Wicklow mountains until the end of 1803, hoping for French help and informed of Robert Emmet's plans for a new uprising.

The North

The northern United Irish leaders did not respond to the call for rebellion on May 23rd. A British official noted that the "quiet of the North" was surprising. He believed that the rebellion's "Popish tinge" (Catholic nature) and France's actions against Protestant areas had helped keep the north calm.

When Robert Simms resigned his command in Antrim on June 1st, despairing of French aid, Henry Joy McCracken took charge. He declared the "First Year of Liberty" on June 6th. There were many local gatherings, but before they could coordinate, most people were hiding their weapons and returning home. The issue was decided the next evening. McCracken, leading four to six thousand men, failed to capture Antrim Town and suffered heavy losses.

In Down, William Steel Dickson, who had taken over from Russell, was arrested with all his "colonels." Under the command of Henry Monro, a young draper, a rising began on June 9th. After a successful skirmish at Saintfield, several thousand marched on Ballynahinch, where they were completely defeated.

Before the Battle of Ballynahinch on June 12th, some reports say the Defenders of County Down withdrew. Their leader was supposedly upset that Munro refused a night attack on the celebrating soldiers, calling it "unfair." Defenders were present at Antrim, but tensions with the Presbyterian United Irishmen may have caused some desertions and delays in McCracken's attack.

The government, confident they could exploit tensions between Presbyterians and Catholics, not only pardoned the rebel soldiers but also recruited them into the Yeomanry. On July 1, 1798, in Belfast, the birthplace of the United Irishmen, it's said that every man wore the Yeomanry's red coat. An Anglican clergyman claimed that "the brotherhood of affection is over." One of McCracken's lieutenants, James Dickey, reportedly said before his execution that northern Presbyterians realized too late that if they had won, they would have had to fight the Roman Catholics.

Despite this, a spirit of resistance remained. Authorities believed that County Down was "re-regimented" by May 1799. Until 1802, while hopes for a French landing remained, United veterans continued night-time arms raids and attacks on loyalists, especially in Antrim. Here, however, they were now organized in Defender groups, which had removed religious references from their oaths.

The West

On August 22, 1798, 1,100 French soldiers landed at Killala in County Mayo. After winning their first battle, the Races of Castlebar, but unable to connect with a new uprising in Longford and Meath, General Humbert surrendered his forces on September 8th. The last action of the rebellion was a slaughter of about 2,000 poorly armed rebels outside Kilala on September 23rd. These rebels included refugees from the Armagh disturbances and were led by James Joseph MacDonnell, a member of Mayo's surviving Catholic gentry.

On October 12th, a second French expedition was stopped off the coast of Donegal, and Tone was captured. Tone, regretting nothing he had done "to raise three million of my countrymen to the ranks of citizen," took his own life before his execution.

Later Conspiracies (1798–1805)

Restoring a United Network

After the rebellion failed, young activists like William Putnam McCabe and Robert Emmet (Thomas Addis Emmet's younger brother), along with veterans Malachy Delaney and Thomas Wright, tried to rebuild the United Irish organization. With advice from imprisoned leaders like Thomas Russell and William Dowdall, they recruited members strictly for military purposes. Instead of open nominations, officers would personally select members based on the authority of a national leadership. Their strategy was again to ask France for an invasion, promising simultaneous uprisings in Ireland and England. McCabe went to France in December 1798, stopping in London first.

In England, the United network had been broken up after Coigley's arrest in March. But a large number of Irish refugees (up to 8,000 former rebels in Manchester), workers' anger over new laws, and protests about food shortages encouraged former conspirators to reorganize. A military system and pike manufacturing spread across the factory districts of Lancashire and Yorkshire. Meetings between county and London delegates resumed. New members took oaths promising "The Independence of Great Britain and Ireland" and "The Equalisation of Civil, Political and Religious Rights." However, all plans in England and Ireland depended on a French invasion.

Hopes were dashed by the Treaty of Amiens in March 1802, which brought a temporary peace. They revived when the war restarted in May 1803. But like in 1798, Napoleon had sent his naval and military forces elsewhere, making an invasion of Ireland impossible. Instead of returning to Ireland, General Humbert was sent in 1803 to re-enslave Haiti.

Emmet's Rebellion

In February 1803, Edward Despard was found guilty of plotting with the United network in London to kill the King and seize the Tower of London. He also planned to start a rebellion in northern factory towns. Robert Emmet, undeterred by this failure, and without French aid, planned to seize Dublin Castle.

Due to several mistakes, the uprising in Dublin on July 23, 1803, only resulted in small street fights. In September, Emmet was executed. While Michael Dwyer's guerrilla fighters in Wicklow and men in Kildare were willing to act, Russell and Hope found that the spirit of rebellion was completely broken among United and Defender veterans in the north. Before his arrest, Emmet asked Myles Byrne to return to Paris to plead for French help again.

In October 1805, any remaining hopes for French intervention were destroyed by the French and Spanish fleets' defeat at the Battle of Trafalgar. A French Irish Legion (a military unit) was sent to fight in Spain instead. The United network slowly fell apart. McCabe and other exiles began seeking terms with the British government to surrender politically and return home.

United Irishmen in Exile

American Society of United Irishmen

In October 1799, a report from Jamaica stated that many United Irish prisoners, "carelessly drafted" into regiments for service in the West Indies, had run away to fight with the Maroons and any French people on the island. This raised fears in the West Indies and the United States that Irish revolutionaries would conspire not only for France but also for her allies, like former slaves in the Haitian Revolution.

In May 1798, William Cobbett, an English writer, began publishing stories in Philadelphia about a "Conspiracy, Formed by the United Irishmen, With the Evident Intention of Aiding the Tyrants of France In Subverting the Government of the United States." He claimed that Irish immigrants, meeting in a school and admitting free blacks, had formed a society committed to an Irish republic and the idea that "a free form of government... [is] the common rights of all the human species." Cobbett saw this as proof of their intention to organize slave revolts and cause widespread rebellion.

This American Society of United Irishmen, proposed by Tone's friend James Reynolds, seemed to have chapters in several port cities like Philadelphia, Baltimore, New York, and Wilmington. William Duane, one of their leaders, defended their vision of citizenship that included "the Jew, the savage, the Mahometan, the idolator." By 1800–1801, United Irishmen were organized as Jeffersonian Democrats in Hibernian societies. In the War of 1812, they achieved their goal of striking a blow against the British Empire and securing their place in American society.

"United Irish" Mutinies in Newfoundland and New South Wales

More reliable reports of United Irish activity came from the British colonies of Newfoundland and New South Wales. In Newfoundland, two-thirds of the main settlement, St. John's, were Irish, as were most of the local British soldiers. In April 1800, there were reports that over 400 men had taken a United Irish oath, and eighty planned to kill their officers and seize their Protestant governors during Sunday service. This mutiny (for which 8 were executed) might have been an act of desperation due to harsh living conditions, but the Irish in Newfoundland would have known about the fight for civil equality and political rights back home. There were reports of communication with United Irishmen in Ireland before the 1798 rebellion, of Paine's pamphlets circulating, and of Irish rebels migrating to the island, adding to local grievances.

In March 1804, stirred by news of Emmet's rising, several hundred United Irish convicts in New South Wales tried to take control of the penal colony and capture ships to return to Ireland. They were poorly armed, and their leader, Philip Cunningham, was captured under a flag of truce. The main group of rebels was defeated in an event loyalists called the Second Battle of Vinegar Hill.

Lasting Impact

Some United Irishmen saw the Acts of Union in 1801, which abolished the Dublin parliament and brought Ireland directly under British rule, as a kind of victory. Archibald Hamilton Rowan, in Hamburg, celebrated "the downfall of one of the most corrupt assemblies that ever existed."

William Drennan at first urged Irishmen to fight the Union. But later, hoping that the British Parliament might eventually achieve his original goal of "a full, free and frequent representation of the people," he seemed to accept it. He reasoned, "What is a country justly considered, but a free constitution?"

In his later years, in the 1840s, Jemmy Hope led meetings of the Repeal Association, which wanted to undo the Acts of Union. Hope had doubts about Daniel O'Connell's movement. The Presbyterian areas in the north, where he believed the "republican spirit" was strongest, never again supported an Irish parliament. They seemed to have a "collective amnesia" about 1798.

In 1799, Thomas Ledlie Birch argued that the United Irishmen were "goaded" into rebellion by violence. But in Ireland, the first public recognition of the United Irishmen came in 1831 with Thomas Moore's book, The Life and Death of Lord Edward Fitzgerald. Moore saw it as a "justification of the men of '98."

Breaking with O'Connell, the Young Irelanders wanted to unite Protestants and Catholics in the fight for tenant rights and land ownership. Charles Gavan Duffy remembered a Quaker neighbor, a former United Irishman, who said that kings and governments weren't the real issue. What mattered was the land from which people got their food.

O'Connell believed that the British government had deliberately caused the rebellion to have an excuse to abolish the Irish parliament. He thought that if the Union was repealed, Protestants in the north would eventually join the majority of the Irish nation. For nationalists, it was a "sad irony" that the descendants of the republican rebels were convinced to see their "connection with England" as a guarantee of their rights.

Unionists argued that those who wanted to repeal the Union misunderstood the United Irishmen's true goals. They insisted there was no paradox in descendants of the United Irishmen supporting the United Kingdom. They believed that if their ancestors had been offered a Union with "Catholic Emancipation, a Reformed Parliament, a responsible Executive and equal laws for the whole Irish people," there would have been "no rebellion." Later, in Northern Ireland, Edna Longley noted that Protestant writers often used 1798, rather than the Easter Rising of 1916, as a key historical event, suggesting a difference from the new Irish state in the south.

A major history of the movement notes that "the legacy of the United Irishmen, however interpreted, has proved as divisive for later generations as the practice of this so-called union did in the 1790s." On the 200th anniversary of the uprising, historian John A. Murphy suggested that what can be celebrated is "the first time entrance of the plain people on the stage of Irish history." The United Irishmen "promoted egalitarianism and the smashing of deference." After their defeat in the Battle of the Big Cross in June 1798, a Protestant vicar told the Catholics of Clonakilty: "Surely you are not foolish enough to think that society could exist without landlords, without magistrates, without rulers... Be persuaded that it is quite out of the sphere of country farmers and labourers to set up as politicians, reformers, and law makers..." What the powerful feared most was "the manifestations of an incipient Irish democracy." Murphy concludes that "the emergence of such a democracy, rudimentary and inchoate, was the most significant legacy" of the United Irishmen.

Notable Members

- Robert Adrain

- John Allen

- William Aylmer

- Riocard Bairéad

- John Binns

- Thomas Ledlie Birch

- James Bartholomew Blackwell

- Harman Blennerhassett

- Oliver Bond

- Myles Byrne

- William Michael Byrne

- John Chambers

- William Paulet Carey

- Thomas Cloney

- Father James Coigly

- John Henry Colclough

- William Corbet

- James Corcoran

- Walter Cox

- Alexander Crawford

- George Cummins

- Philip Cunningham

- Malachy Delaney

- James Dempsey

- Edward Despard

- John Devereux

- James Dickey

- William Steel Dickson

- James Dixon

- William Dowdall]

- William Drennan

- William Duane

- William Duckett

- Michael Dwyer

- Robert Emmet

- Thomas Addis Emmet

- John Esmonde

- Peter Finnerty

- Lord Edward FitzGerald

- Henry Fulton

- John Glendy

- Watty Graham

- Cornelius Grogan

- William Henry Hamilton

- Bagenal Harvey

- Henry Haslett

- Edward Hay

- Joseph Holt

- James "Jemmy" Hope

- Henry Howley

- Edward Hudson

- Peter Ivers

- Henry Jackson

- William Jackson

- Charles Edward Jennings

- Edward Jordan

- Father Mogue Kearns

- John Kelly

- John Keogh

- Matthew Keogh

- Richard Kirwan

- Valentine Lawless

- William Lawless

- Edward Lewins

- Alexander Lowry

- Thomas McCabe

- William Putnam McCabe

- James McCartney

- Roddy McCorley

- Richard McCormick

- Henry Joy McCracken

- James Joseph MacDonnell

- James MacHugo

- Gilbert McIlveen

- Arthur McMahon

- Leonard McNally (informer)

- William James MacNeven

- Samuel McTier

- Francis Magan

- St John Mason

- Hervey Montmorency Morres

- John Moore

- Thomas Muir, (honorary member)

- Henry Munro

- John Murphy

- Michael Murphy

- Samuel Neilson

- Edward John Newell (informer)

- Arthur O'Connor

- Roger O'Connor

- Padraig Gearr Ó Mannin

- James Orr

- William Orr

- Thomas Paine, honorary member

- Anthony Perry

- James Porter

- James Reynolds

- Philip Roche

- Archibald Hamilton Rowan

- Thomas Russell

- William Sampson

- Timothy Shanley

- The Sheares Brothers

- William Sinclair

- Robert Simms

- Whitley Stokes

- John Sweetman

- John Swiney

- Denis Taaffe

- James Napper Tandy

- Bartholomew Teeling

- Charles Hamilton Teeling

- John Templeton

- John Tennant

- William Tennant

- Theobald Wolfe Tone

- Samuel Turner (informer)

- Staker Wallace

- David Bailie Warden

- John Campbell White

- Thomas Wright

Female Members/Supporters

- Henrietta Battier

- Anne Devlin

- Bridget Dolan

- Lucy Anne FitzGerald

- Pamela FitzGerald

- Elizabeth "Betsy" Gray

- Jane Greg

- Mary Anne Holmes

- Cherry Crawford Hyndman

- Margaret King (Lady Mount Cashell)

- Mary Ann McCracken

- Martha McTier

- Mary Moore

- Matilda Tone