1794 Treason Trials facts for kids

The 1794 Treason Trials were a series of important court cases in Britain. The government, led by William Pitt the Younger, wanted to stop a growing movement of people who wanted big changes in how the country was run. These people were called "radicals."

More than 30 radicals were arrested. Three main leaders were put on trial for treason, which is a very serious crime against the king and country. These men were Thomas Hardy, John Horne Tooke, and John Thelwall. In November 1794, all three were found not guilty by different juries. People celebrated their freedom in the streets. These trials were a follow-up to earlier trials in 1792 and 1793 against people who wanted to change Parliament.

Contents

Why the Trials Happened

The 1794 Treason Trials happened because of a mix of British politics and the French Revolution.

Changes in Britain

In the 1770s and 1780s, some members of Parliament wanted to change Britain's voting system. Only a small number of people could vote for Members of Parliament (MPs), and many seats in Parliament were simply bought.

People like Christopher Wyvill and William Pitt the Younger wanted to add more seats to the House of Commons. Others, like the Duke of Richmond and John Cartwright, wanted bigger changes. They suggested paying MPs, stopping corruption in elections, having elections every year, and letting all men vote. These early efforts to change the system did not succeed.

Impact of the French Revolution

When the French Revolution began, it showed how much power ordinary people could have. This made the British reform movement strong again. Many political discussions in Britain in the 1790s were started by Edmund Burke's book, Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790).

Burke had supported the American Revolution, but he criticized the French Revolution. He also criticized British radicals who liked the early stages of the French Revolution. Radicals thought the French Revolution was like Britain's own Glorious Revolution in 1688, which limited the king's power. But Burke said it was more like the English Civil War (1642–1651), where King Charles I was executed. He saw the French Revolution as a violent overthrow of a rightful government.

Burke believed that people do not have the right to revolt against their government. He argued that governments and societies are built on shared traditions. If these traditions are challenged, it could lead to chaos.

British supporters of the French Revolution quickly responded. Mary Wollstonecraft wrote Vindication of the Rights of Men, and Thomas Paine wrote Rights of Man. This debate, called the "Revolution Controversy", covered topics like how government should be set up, human rights, and the separation of church and state.

Rise of Radical Groups

The year 1792 was a very important year for the radical movement. Key books like Rights of Man were published, and radical groups became very influential. Many new groups started because of Rights of Man.

Important groups included the Sheffield Society for Constitutional Information, the London Corresponding Society (LCS), and the Society for Constitutional Information (SCI). These groups were made up of regular people like craftspeople and merchants. The government only became worried when these groups joined with a more upper-class group called the Society of the Friends of the People.

On May 21, 1792, the government issued a royal announcement against writings that encouraged rebellion. The number of trials for sedition (actions or words encouraging rebellion) greatly increased in the 1790s. The British government feared an uprising like the French Revolution. They took strong steps to stop the radicals.

They arrested more people and sent spies into radical groups. They threatened to take away licenses from pubs that hosted political discussions. They also checked the mail of people they suspected. The government also supported groups that broke up radical events and attacked radicals in newspapers.

In 1793, the government passed the Aliens Act. This law controlled who could enter Great Britain. Immigrants had to register their names, jobs, and addresses. This law reduced the number of immigrants because the government feared spies. Radicals felt this period was like a "system of terror."

Early Trials

Before the main treason trials, some other important cases happened.

Thomas Paine's Trial

The government did not immediately go after everyone who disagreed with them. Thomas Paine's publisher was charged in May 1792 for printing Rights of Man. But Paine himself was not charged until the royal announcement against rebellious writings.

Even then, the government did not actively chase him, except for spying and spreading bad stories about "Mad Tom." Paine's trial was delayed until December. He left for France before the trial, seemingly with the government's approval. They seemed more interested in getting rid of him than trying him in person. The government also might not have wanted to try Paine in person because he could have used the trial to spread his political ideas.

When the trial happened on December 18, 1792, the outcome was already clear. The government had been attacking Paine in the newspapers for months. The judge had even discussed the prosecution's arguments with them beforehand.

The lawyer Thomas Erskine defended Paine. He argued that Paine's book was part of a long tradition of English political writing. He also pointed out that Paine was responding to a book by a Member of Parliament, Burke. The government's lawyer argued that Paine's book was for readers "whose minds cannot be supposed to be conversant with subjects of this sort." He even said its cheap price showed it was not serious. The jury quickly decided Paine was guilty without even hearing all of Erskine's arguments.

John Frost's Trial

John Frost was a member of the SCI and a friend of Paine. In November 1792, he argued with a friend in a pub about the French Revolution. He was heard saying "Equality, and No King." Publicans reported this to government spies.

When Frost went to Paris later that month, the government declared him an outlaw. They encouraged him to stay in France. But Frost returned to challenge the government and turned himself in. Some thought the government was embarrassed to try Frost because he used to be friends with Pitt. But on May 27, he was tried for sedition. The government's lawyer said Frost "was a man whose seditious intent was carried with him wherever he went." The jury found him guilty.

Daniel Isaac Eaton's Trial

Daniel Isaac Eaton published a popular magazine called Politics for the People. He was arrested in December 1793 for printing something by John Thelwall. Thelwall had given a speech that included a story about a mean rooster named "King Chanticleer" who was beheaded for being a tyrant. Eaton printed this story.

Eaton was kept in prison for three months before his trial. This was an attempt to make him and his family lose all their money. In February 1794, he was tried and defended by John Gurney. Gurney argued that the story was about tyranny in general, or about King Louis XVI of France. He said he was shocked anyone could think it was about King George III of England. Gurney even joked that the government's lawyer was the one guilty of spreading rebellious ideas. He said the lawyer, not Eaton, had made King George III seem like a tyrant. Everyone in the courtroom laughed, and Eaton was found not guilty. After this, the number of people joining radical groups greatly increased.

The Main Treason Trials of 1794

After Eaton's trial, the radical groups became more popular. In the summer of 1793, several groups decided to meet in Edinburgh. They wanted to figure out how to gather "a great Body of the People" to convince Parliament to make reforms. The government saw this meeting as an attempt to create a rival parliament.

In Scotland, three leaders of this meeting were tried for sedition. They were sentenced to 14 years of service in Botany Bay (a distant colony). These harsh sentences shocked the country. While some groups thought a rebellion might be needed, their words never turned into actual armed fighting. Some groups planned to meet again if the government became more hostile, for example, if they suspended habeas corpus (a legal right that protects against unlawful imprisonment). In 1794, a plan to meet again was circulated, but it never happened.

However, the government was scared. They arrested six members of the SCI and 13 members of the LCS. They suspected them of "treasonable practices." The government claimed these groups were planning to set up "a pretended general convention of the people." They said this was against Parliament's authority and would lead to "anarchy and confusion" like in France. More than 30 men were arrested in total. Among them were Thomas Hardy, the secretary of the LCS; the language expert John Horne Tooke; the writer Thomas Holcroft; the minister Jeremiah Joyce; the writer and speaker John Thelwall; the bookseller Thomas Spence; and the silversmith John Baxter.

After the arrests, the government formed two secret committees. These committees studied the papers they had taken from the radicals' homes. After the first committee's report, the government passed a law in the House of Commons to suspend habeas corpus. This meant that people arrested for suspected treason could be held without bail or charges until February 1795.

In June 1794, the second committee reported. They claimed the radical groups had planned to "over-awe" (intimidate) the king and Parliament with a large gathering of people. They even suggested the groups wanted to overthrow the government and create a French-style republic. They said the groups tried to gather many weapons, but no proof was found.

The arrested men were charged with various crimes, but the most serious were seditious libel and treason. The government tried to say the radicals had committed a new kind of treason, which they called "modern" or "French" treason. Old treason laws were about replacing one king with another. But these democrats wanted to get rid of the king and the whole system. The old treason law from 1351 did not fit this new idea of treason well.

The government's lawyer, Sir John Scott, decided to base the charges on the idea that the groups were planning to wage war against the king. He claimed they wanted to overthrow the government, remove the King, and even kill him. For this, they supposedly planned to cause rebellion.

At first, the men were held in the Tower of London, but later they were moved to Newgate prison. The entire radical movement was also on trial. It was believed that 800 more arrest warrants were ready if the government won its case.

Thomas Hardy's Trial

Hardy's trial was the first. His wife had died while he was in prison, which made people feel sorry for him. Thomas Erskine defended him again. He argued that the radicals had only suggested what the Duke of Richmond (who was now against reform) had suggested in the 1780s. He also said their plan for a meeting of delegates was similar to a plan Pitt himself had once supported.

The government could not show any real proof of an armed rebellion. The government's lawyer spoke for nine hours to start the trial. A former high judge, Lord Thurlow, said there was "no treason." Treason must be "clear and obvious." The legal expert Edward Coke had said treason should be proven with "good and sufficient proof," not just guesses.

Erskine's defense was very effective. He said the prosecution's case was based on "imagination." He claimed, as he had in earlier trials, that it was the prosecution, not the defense, that was "imagining the king's death." He also questioned the government's spies in a way that made their evidence seem unreliable.

After a nine-day trial, which was very long for that time, Hardy was found not guilty. The head of the jury fainted after giving the verdict. A happy crowd carried Hardy through the streets of London.

Erskine said that the radical groups, especially the London Corresponding Society and the Society for Constitutional Information, wanted a revolution of ideas, not a violent one. He said they represented the new ideas of the Age of Enlightenment. Erskine's defense was also helped by books like William Godwin's Cursory Strictures.

John Horne Tooke's Trial

John Horne Tooke's trial came after Hardy's. During this trial, Pitt himself had to testify and admit he had attended radical meetings. Throughout his trial, Horne Tooke acted bored but also made funny, disrespectful remarks.

One person watching noted that when the court asked if he would be tried "by God and his Country," he looked at the court for a few seconds with a meaningful look. Then he shook his head and said strongly, "I would be tried by God and my country, but—!" After a long trial, he was also found not guilty.

Horne Tooke later said he owed his life to Godwin’s Cursory Strictures. This book was published anonymously and led to legal arguments that took up a lot of time on the first day of the trial.

After these two trials, all the other members of the SCI were released. It became clear to the government that they would not win any more cases.

John Thelwall's Trial

John Thelwall was the last to be tried. The government felt they had to try him because newspapers supporting the king said his case was especially strong. While waiting for his trial, he wrote poems criticizing the whole process.

During Thelwall's trial, members of the London Corresponding Society said that Thelwall and the others had no real plans to overthrow the government. They said that details about how reform would happen were just "an afterthought." This weakened the government's claim that the group was planning a rebellion. Thelwall was also found not guilty. After his acquittal, all the remaining cases were dropped.

What Happened Next

Even though all the people in the Treason Trials were found not guilty, the government and those who supported the king still thought they were guilty. The Secretary at War, William Windham, called the radicals "acquitted felons." William Pitt and the government's lawyer called them "morally guilty." Many people agreed that the radicals got off because the old treason law was out of date.

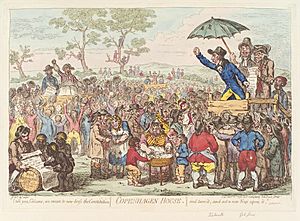

In October 1795, crowds threw trash at the king and insulted him. They demanded an end to the war with France and lower bread prices. Because of this, Parliament passed the "gagging acts." These were the Seditious Meetings Act and the Treasonable Practices Act. These new laws made it almost impossible to have public meetings, and speaking at such meetings was greatly restricted.

Because of these new laws, groups that were not directly involved with the Treason Trials, like the Society of the Friends of the People, broke up. British "radicalism faced a severe set-back" during these years. It was not until much later that any real reforms could happen.

Even though the trials were not victories for the government, they did achieve their goal. Most of the men involved, except Thelwall, stopped being active in radical politics. Many others also stopped because they feared what the government might do. Few people took their place.

Images for kids

-

Thomas Paine; a painting by Auguste Millière (1880)

-

James Gillray's cartoon of Thelwall speaking at Copenhagen Fields on October 26, 1795

| Anna J. Cooper |

| Mary McLeod Bethune |

| Lillie Mae Bradford |