London Corresponding Society facts for kids

| Formation | 25 January 1792 |

|---|---|

| Purpose | Radical parliamentary reform |

| Headquarters | London |

|

Key people

|

Thomas Hardy, Joseph Gerrald, Maurice Margarot, Edward Despard |

The London Corresponding Society (LCS) was a group of local reading and debating clubs in Britain. After the French Revolution, they worked to make the British Parliament more democratic. Unlike other groups at the time, the LCS was mostly made up of working men, like artisans, tradesmen, and shopkeepers. It was also organized in a democratic way, meaning members had a say.

The government, led by William Pitt the Younger, saw the LCS as a threat. They thought the society was linked to French revolutionary ideas and groups like the United Irishmen. The government even accused some LCS leaders of planning against the King. After naval protests in 1797 and the Irish Rebellion in 1798, the government took stronger action. In 1799, a new law officially shut down the LCS and other similar groups.

Contents

How the LCS Started

In the late 1700s, new ideas from the Enlightenment and events like the American Revolution and French Revolution inspired many people in Britain. They wanted more say in how their country was run. Groups formed to support ideas like popular rule and fair government.

In northern England, some Protestant groups, especially Unitarians, supported the Society for Constitutional Information (SCI). This group was founded by people like Major John Cartwright. He wrote a book in 1776 that called for all men to have the right to vote, secret ballots, yearly elections, and equal voting areas.

In 1788, some SCI members formed the Revolution Society. They celebrated the Glorious Revolution of 1688 and called for important rights. These included freedom of thought, freedom of the press, and fair elections. After 1792, the focus of reform shifted from the Revolution Society to the SCI, and then to the new London Corresponding Society.

Thomas Hardy, a shoemaker from Scotland living in London, was inspired by pamphlets from Dr. Richard Price. Price was a Unitarian minister and a strong supporter of reform. Hardy also read about a group in Ireland that wanted to reform their government. This made him believe that working men needed their own reform club.

People said Hardy was very good at organizing and always spoke clearly and to the point.

Hardy and his friends started the new society at a time when many people were interested in politics. This was partly because of Thomas Paine's book, Rights of Man, published in 1791 and 1792. Paine's book defended the French Revolution and was read by many reformers, workers, and skilled factory hands across Britain. It sold millions of copies.

How the LCS Was Organized

A Democratic Way to Work

The British government was suspicious of the LCS from the start. They even sent spies to join the group. The government also worried about the LCS working with French agents. To deal with this, and to copy groups in Sheffield, the LCS set up a decentralized, democratic system.

The LCS was organized into "divisions." Each division had smaller "tithings" of no more than ten members. Each division met twice a week to discuss business and read political texts.

Unlike some older reform clubs, the LCS allowed all members to join in debates. They could also elect their leaders, such as tithing-men or delegates. Rules made sure that no one person took over the discussion. One member, Francis Place, remembered that no one could speak a second time on a topic until everyone else who wanted to had spoken once.

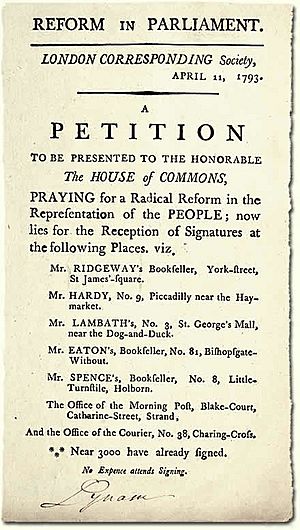

The LCS released its first public statement in April 1792. Similar groups also started in other cities like Manchester, Norwich, and Stockport.

Who Joined the LCS?

By May 1792, the LCS had nine divisions, each with at least thirty members. At its peak in late 1795, it might have had between 3,500 and 5,000 members in 79 divisions. The LCS charged only a penny a week to join, which meant almost anyone could become a member. This was much cheaper than the SCI, which charged four guineas a year.

Most members were skilled workers like shoemakers, weavers, and watchmakers. These jobs gave them enough independence to speak their minds without fear of losing their jobs.

While the LCS was mainly for skilled workers, some people with higher social standing also joined. Many came from existing debating societies. They brought important political connections and skills. Lawyers like Felix Vaughan and Joseph Gerrald were very helpful because members often faced court cases. Doctors like James Parkinson and John Gale Jones were also members. However, the LCS's rules meant that these prominent members did not get special treatment. Thomas Hardy especially wanted to make sure ordinary members felt confident speaking up for themselves.

A Group for Men

Some debating societies at the time included women, and women even formed their own groups to ask for equal education and rights. While some LCS members, like Thomas Spence, supported political rights for women, the LCS itself seemed to be a group for men. Their meetings often took place in taverns and coffee houses, which were mostly male spaces. Records of women in their meetings are rare.

In August 1793, the LCS committee approved a plan to form a female Society of Patriots. By September, a government spy reported that a women's society was meeting. The LCS sent delegates to teach them. However, it seems women were never allowed to become full members of the LCS itself. Women did attend large LCS protests.

Famous Members

One early famous member was Olaudah Equiano, a former slave from the West Indies and an abolitionist. In the early 1790s, Equiano was touring Britain with his autobiography. He helped the LCS connect with other groups, including the United Irishmen.

Other notable members included Thomas Paine, the radical poet William Blake, and Joseph Ritson, an antiquarian who helped start modern vegetarianism.

"London's Sans-Culottes"

Despite having some well-known members, government spies reported that most of the LCS members were from "the very lowest order of society." The government worried that English Jacobins (radical revolutionaries) in the LCS were like the sans-culottes (working-class revolutionaries) in Paris. Some working-class members did take Paine's republican ideas to an extreme, wanting a complete democracy without a king or nobles.

One of the most famous radical democrats was Thomas Spence. He had protested the enclosure of shared land in his hometown. Spence re-published a pamphlet called The Real Rights of Man, which argued that land should be owned in common and managed democratically. In 1797, he wrote The Rights of Infants, which suggested that children should have a right to be free from poverty and abuse.

Equality, Not "Levelling"

From the start, the LCS was accused of wanting to "level" society, meaning they wanted to get rid of all differences in social rank and property. This idea was spread widely in a pamphlet called Village Politics (1793), written by Hannah More. It was a simple conversation where a mason learned that "Liberty and Equality" meant associating with "levellers" who wanted to take away everyone's property.

The LCS responded with "An Explicit Declaration of the Principles and View of the L.C.S." They stated that those who wanted to reform Parliament would never support "the equalization of property." The LCS did not focus on social issues. They believed that fixing the unfair way Parliament was set up would solve problems like "oppressive Taxes, unjust Laws, restrictions of Liberty, and wasting of the Public Money."

The Conventions and Pitt's "Reign of Terror"

The First Edinburgh Convention

In November 1792, the LCS published an "Address" to other reform groups in Britain. They expressed confidence that they could achieve a democratic government through peaceful means. A national meeting, or convention, was called for Edinburgh in December.

Thomas Muir, a radical delegate from Scotland, hosted the LCS delegates. He spoke only about constitutional ideas. An address from the United Irishmen was accepted only after removing any suggestions of treason against the union of Scotland and England. However, using the word "Convention" and an oath to "live free or die" worried the authorities. Some minor legal actions were taken.

The Edinburgh Trials

By the time LCS delegates attended their second convention in Edinburgh in October 1793, the situation had changed a lot. Britain was at war with France. Any link to France or support for its policies was now seen as treason. In May 1793, the House of Commons refused to even consider petitions for reform.

Reformers were trying to get support for a reformed Parliament and a constitutional monarchy. But because they had supported the French Revolution early on, they now had to defend French policies they didn't agree with at home. These included the execution of the French king and the confiscation of church property.

After Muir returned to Scotland, he was accused of treason. Even though the evidence was mostly just his political views, a jury found him guilty in August 1793. He was sentenced to 14 years of transportation (being sent to a distant colony). The secretary of the second Edinburgh convention, William Skirving, and the two LCS delegates, Joseph Gerrald and Maurice Margarot, faced the same fate.

Gerrald and Margarot had been elected by the LCS's first large outdoor meeting, attended by about 4,000 people. Gerrald had written a pamphlet suggesting that a national convention could have more legitimacy than the corrupt Parliament.

Margarot had lived in Paris during the French Revolution. This allowed the authorities to suspect him of being a French spy.

The London Trials

The government's actions greatly reduced the number of popular societies outside London. In London, Hardy and John Baxter, who took over as chairman, continued to call for an end to the war with France. Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger responded by seizing the papers of the London societies.

In May 1794, serious charges of treason were brought against thirty leading radicals. These included Hardy, Thomas Spence, the writer Thomas Holcroft, the speaker John Thelwall, and John Horne Tooke. However, their trials in November did not go as planned. Juries in London were not as willing as those in Edinburgh to see political opinions as proof of plots against the King. When the evidence against Hardy failed to convince the jury, the charges against his friends also seemed weak.

Hardy faced a personal tragedy during his trial. His wife was attacked by a mob and later died in childbirth. After his release, Hardy did not return to his role in the Society.

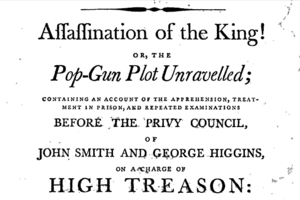

More arrests were made during these trials. Paul Thomas LeMaitre and others were accused of being involved in the "Popgun Plot." This was an alleged plan to assassinate King George III with a poisoned dart from an airgun. In May 1796, these cases also fell apart.

The reformers were not allowed to celebrate their victory easily. The LCS bookseller, John Smith, provocatively renamed his shop "The Pop Gun." He also sold a pamphlet that criticized soldiers, clergymen, and lawyers. He was sentenced to two years of hard labor for seditious libel (publishing something that encourages rebellion).

Before the treason trials, the right to a speedy trial (habeas corpus) had been suspended. This allowed the government to detain six members of the Society, including Thomas Spence. Parliament allowed the government to hold people without charge if they suspected a "traitorous and detestable conspiracy" to overthrow the government and bring in French-style chaos.

Changes and the End of the LCS

The Last Big Meeting

In the summer of 1795, people were tired of the war, and bad harvests led to more protests. There was even an attack on the Prime Minister's home. The LCS started growing again, from 17 divisions in March to 79 in October. Tens of thousands of people attended their general meetings.

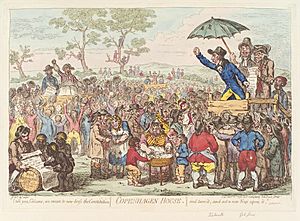

The LCS called a huge meeting for October 26, 1795, at Copenhagen Fields in Islington. Veteran reformers like Joseph Priestley and John Thelwall spoke. They were joined by LCS leaders like John Ashley (a shoemaker), John Binns (a plumber's laborer), John Gale Jones (a surgeon), and William Duane (an Irish-American editor). Crowds were estimated to be over 200,000 people.

At the meeting, Binns and Ashley declared that if the British nation faced continued war, famine, and corruption, the LCS would be a "powerful organ" to bring "peace... universal suffrage and annual parliaments." Three days later, George III's carriage windows were smashed by a crowd shouting "No King, No Pitt, No war" as he went to Parliament.

The "Gagging Acts"

Using this incident as an excuse, the government introduced the "Gagging Acts" in 1795. The Seditious Meetings Act and the Treason Act made writing and speaking against the government as serious as treason. They also made it a serious crime to encourage hatred of the government. These laws required licenses for public meetings, lectures, and reading rooms. This, along with magistrates closing taverns and bookshops that were centers of radical activity, stopped the LCS's publishing program and limited their ability to spread their message.

The increase in LCS membership and activity in the summer of 1795 was short-lived. The problem was not just Pitt's "reign of terror."

The Decline of Paine's Influence

Thomas Paine had been a very popular leader of public opinion. But after a difficult period in France, where he was imprisoned, he wrote his second major work, The Age of Reason, published in 1796 and 1797. In this book, Paine criticized the Christian Bible and churches. This made many religious groups, who had previously supported reform, now turn away from the movement.

By 1795, some Methodists had already left the LCS to form their own group. One prominent member, Richard Lee, was reportedly expelled from the LCS for refusing to sell Paine's new book.

United Britons

The government's actions made it harder for reformers to work peacefully. This led some radicals to consider using force, hoping for help from France. In this, they were supported by the United Irishmen. In the summer of 1797, after naval protests, an Irish priest named James Coigly arrived from Manchester. He and others helped turn the Manchester Corresponding Society into the republican United Englishmen. These "United men" spread to other towns like Stockport and Birmingham. They were organized like the United Irishmen.

Coigly, claiming to be from the United Irish leaders, met with LCS members. These included Edward Despard and the brothers Benjamin and John Binns. Meetings were held where delegates from London, Scotland, and other regions reportedly agreed to "overthrow the present Government, and to join the French." (In December 1796, bad weather had stopped a major French invasion of Ireland).

In March 1798, Coigly was arrested with others as they were about to leave for France. An address to the French leaders, found on Coigly, suggested a mass movement ready for rebellion. This was enough proof of their intent to encourage a French invasion. Coigly faced severe punishment in June.

Turning Away from Conspiracy and Final Suppression

On January 30, 1798, the LCS had sent an address to the United Irishmen, saying that if uniting for reform was treason, then they too were "Traitors." However, many people were becoming disappointed with France. By the time Coigly was arrested, most members felt that working with the French was a bad idea. The LCS committee even agreed that if France invaded, members would join their local, government-approved militias.

On April 19, 1798, as this was being decided, the committee meeting was raided by police. Along with similar raids in Birmingham and Manchester, 28 people were arrested. These included Thomas Evans, Edward Despard, and John Binns. The next day, Pitt again suspended habeas corpus, meaning the government didn't need to show evidence for holding them. The prisoners were held without charge until peace with France was temporarily made in 1801.

According to Francis Place, this action ended the Society. Members stopped meeting. A final law in 1799 specifically banned the LCS by name, along with the United Englishmen, United Scotsmen, United Britons, and United Irishmen.

Despard, who had protested against betraying the United Britons, faced severe punishment for being linked to their remaining members in 1803.

What the LCS Left Behind

In his book The Making of the English Working Class (1963), historian E. P. Thompson said the London Corresponding Society was very important. He believed it helped create a "working-class consciousness" in England. This means working people started to feel they had common interests and that these interests were different from (and often against) those of other groups.

Thompson also suggested that the LCS showed that working people could be "civil, rational, thoughtful, and peaceful."

These achievements helped lead to the popular movements that resulted in the 19th-century Reform Parliamentary Bills. Francis Place lived to be active in the movement for the first of these, the Reform Act of 1832. In 1839, Place was invited to be a delegate for the London Working Men's Association. This group was part of the Chartist movement, which continued the fight for workers' rights and parliamentary reform.

Selected Members

- John Baxter

- John Binns

- William Blake

- Edward Despard

- Basil William Douglas

- William Duane

- Olaudah Equiano

- Thomas Evans

- Joseph Gerrald

- William Hamilton

- Thomas Hardy

- William Hodgson

- John Gale Jones

- Maurice Margarot

- Thomas Paine

- James Parkinson

- Francis Place

- Joseph Ritson

- Thomas Spence

- John Thelwall

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |