Edward Despard facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Edward Marcus Despard

|

|

|---|---|

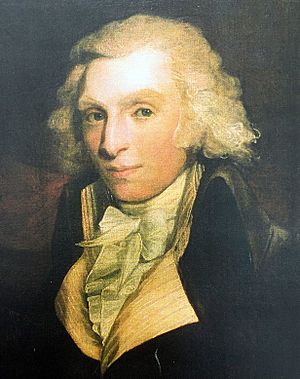

Attributed to George Romney

|

|

| Born | 1751 Coolrain, Camross, Queen's County, Kingdom of Ireland

|

| Died | 21 February 1803 Horsemonger Lane Gaol, London

|

| Cause of death | Execution by hanging |

| Nationality | |

| Occupation | Soldier, colonial administrator, revolutionary |

| Employer | |

| Movement | |

| Criminal charge(s) | High treason |

Edward Marcus Despard (1751–1803) was an Irish officer who served the British Crown. He became well-known for treating all people equally, no matter their race, when he was a leader in the colonies. Later, after returning to London, he became a republican who believed in a government without a king. Despard joined groups like the London Corresponding Society and the United Irishmen. He was put on trial and executed in 1803, accused of leading a plan to assassinate King George III.

Contents

Early Life and Military Career

Edward Despard was born in 1751 in Coolrain, Queen's County, Kingdom of Ireland. He was the youngest of eight children. His family were Protestant landowners. His father and grandfather made their land bigger by taking over common areas that local farmers used to share. This led to some local protests called Whiteboy disturbances when Despard was a child.

Edward went to the Quaker School in Ballitore, County Kildare. This school taught subjects like math, classic literature, and modern languages. From age eight, Despard also learned how to be a "gentleman and a soldier" while working for the Lord Hertford. Lord Hertford was an ambassador and later a leader in Ireland.

In 1766, when he was fifteen, Despard joined the British Army, just like his older brothers. One of his brothers, John Despard, later became a general. Edward started as an ensign in the 50th Foot regiment.

Service in the Caribbean

Despard was sent to Jamaica with his regiment. He worked as an engineer, building defenses. In 1772, he was promoted to lieutenant. His job meant he worked with many different groups of people, including free black people and Miskitos. Some historians think this experience made him more understanding of different cultures.

During the American War of Independence, Despard fought bravely in battles against the Spanish. He fought alongside Horatio Nelson in the San Juan expedition in 1780 and became a captain. Two years later, he led British forces to take back settlements on the Mosquito Coast from the Spanish. For this, he was praised by the king and promoted to colonel.

While on these missions, Despard worked closely with the Miskito people, who were of African and Indian heritage. Olaudah Equiano, a former slave who had lived with them, wrote that "These Indians live under an almost perfect equality." He noted that they did not try to gather lots of wealth, and that the constant effort to get ahead, seen in other societies, was not found among them.

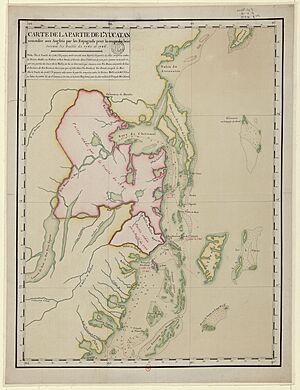

Equality in Honduras

After the war ended in 1783, Despard was made the Superintendent of British areas in the Bay of Honduras (which is now Belize). He was told to help British people, called "Shoremen," who had to leave the Miskito Coast. Despard decided to help them without "any distinction of age, sex, character, respectability, property or colour." This meant he treated everyone the same, no matter their background or skin color.

He gave out land by lottery, where even "the meanest mulatto or free negro has an equal chance." This upset the "Baymen," who were slave-owning loggers. Despard also set aside land for everyone to use, which was the opposite of what his own family had done in Ireland. He also tried to keep food prices low for poorer people.

The Home Secretary, Lord Sydney, suggested that it was not smart to treat "affluent settlers and people of a different description, particularly people of colour" equally. Despard replied that "the laws of England ... know no such distinction." He had also stopped a local law that kept Jewish merchants out of the Bay.

The Baymen complained that Despard's rules would make enslaved people want to revolt. Because of these complaints, Lord Sydney's successor, Lord Grenville, called Despard back to London in 1790.

Despard gave Grenville a long report where he called the Baymen an "arbitrary aristocracy" (a group of powerful people who ruled unfairly). He showed that he had won a big election before he left, proving that many people supported his ideas. However, Grenville was not interested in giving more people the right to vote.

After Despard left, his work in the Bay was undone. By the 1820s, the settlement had seven different legal groups based on skin color.

Family Life in London

Before leaving the Bay, Despard married Catherine in 1790. She was the daughter of a free black woman from Kingston, Jamaica. He came to London with Catherine and their young son, James, as his recognized family. At the time, it was very unusual for a couple of different races to be openly married in England. However, their marriage did not seem to be publicly challenged. This might show that people were more open-minded about race during that time.

When Despard was arrested in 1798, the government tried to make Catherine look bad because she spoke up for her husband. They only said she was of the "fair sex," meaning they thought women were not as smart or capable. In the House of Commons, an Irish Member of Parliament, John Courtenay, read a letter from Catherine. She described her husband being held "in a dark cell, not seven feet square, without fire, or candle, chair, table, knife, fork, a glazed window, or even a book." The attorney general, Sir John Scott, suggested that Catherine was just a puppet for political troublemakers. He said her letter was "a little beyond their style in general," implying women could not write so well.

Around the time the Despards arrived in London, Olaudah Equiano was promoting the idea of openly mixed-race marriages. Equiano, who was married to an English woman, asked why people should not marry freely "without distinction of the colour of a skin?"

Later generations of Despard's family denied Edward and Catherine's marriage. Family writings called Catherine his "black housekeeper" or "the poor woman who called herself his wife." Their son James was also written out of the family history.

Political Activism in London

After returning to London, Despard did not get another military job. He also faced lawsuits from his enemies in the Bay. He ended up in a debtors' prison for two years because he owed money. While there, he read Thomas Paine's Rights of Man. This book supported the idea of "Universal Equality," which was what Despard had tried to achieve in Honduras.

By the time Despard was released in 1794, Paine had gone to France. Britain was now at war with France. In both Britain and Ireland, some people who liked Paine's ideas started to think about using force to get universal voting rights and annual parliaments.

In 1795, crowds attacked the prime minister's home and surrounded the King. Despard was questioned after a riot. The government then passed strict laws called the "Gagging Acts." These laws made "seditious" (rebellious) meetings illegal and made even thinking about using force a serious crime.

Joining Radical Groups

Despard joined the London Corresponding Society (LCS), a group that wanted political reform. He quickly became part of its main committee. He also took a pledge for the United Irishmen. This group wanted "equal, full and adequate representation" for all people in Ireland. At this time, the Irish movement was thinking about a French-supported uprising.

In 1797, a Catholic priest named James Coigly came to London. He met with leading Irish members of the LCS, including Despard. They held meetings as the "United Britons." Delegates from London, Scotland, and other regions agreed to "overthrow the present Government, and to join the French as soon as they made a landing in England."

It seems Despard was a key link between British republicans and France. In June 1797, a government spy reported that a United Irish group, going to France through London, asked Despard for travel documents.

In December 1797, Coigly returned from France with news of French invasion plans. However, in February 1798, he and Arthur O'Connor were arrested while trying to cross the English Channel. Coigly was caught with a letter to the French government from the United Britons. He was found guilty of treason and hanged in June.

Despard, who had met Coigly, stayed in touch with another United Irishman, Valentine Lawless. He was reported to be attending secret meetings in London pubs.

Imprisonment

The government cracked down on the London Corresponding Society. On March 10, Despard was arrested in Soho. He was held without charge for three years in Coldbath Fields, a high-security prison. Catherine Despard tried hard to get him released.

During this time, the authorities also saw the influence of United Irishmen in the Spithead and Nore mutinies of 1797, where sailors protested. More strict laws were passed. The Corresponding Societies were shut down, and the Combination Laws of 1799 and 1800 made it illegal for workers to form unions.

Release and Renewed Activity

Despard was released in May 1802, as fighting with France had stopped. He had not been charged with any crime. There was no sign he planned to restart his political activities; he had even asked to be sent away from England. But he went back to Ireland and met with William Dowdall, another political prisoner who had just been released.

Dowdall and others were in touch with younger activists like Robert Emmet. These young men wanted to reorganize the United Irishmen as a secret military group. Their goal was to work with French forces for another invasion, with uprisings happening at the same time in Ireland and England.

Despard might also have been influenced by what he saw in his home county. Government spies reported that the Rebellion of 1798, though put down, was "by no means suppressed."

In England, many Irish refugees, angry workers, and ongoing protests about food shortages led to new organizing among former activists. Secret military groups and pike manufacturing began to spread in areas like Lancashire and Yorkshire. Meetings between leaders from different counties and London started again.

Treason Trial and Execution

On November 16, 1802, Despard was arrested again. He was at a meeting of 40 working men at a pub in Lambeth. The next day, he was questioned and charged with High Treason. Government spies claimed he was the leader of a plot to assassinate King George III and take over the Tower of London and Bank of England.

Despard's trial began on February 7, 1803. The prosecutor, Spencer Perceval, said that others at the pub had discussed a plan for an uprising. However, the pub did not seem to be the main place for the conspiracy, and Despard had only been there once before his arrest. To link Despard to the plot, the prosecution relied heavily on his name being mentioned in letters from the United Irishmen. But these mentions were often from people Despard had never met.

It is possible that Despard was meant to be just a public figurehead for an uprising. He was chosen because he had become known and gained sympathy due to his harsh imprisonment.

Lord Nelson, famous for his victory in the Battle of the Nile, spoke as a character witness for Despard. He said, "We went on the Spanish Main together; we slept many nights together in our clothes upon the ground." Nelson added that Despard had shown great loyalty to his country. However, Nelson had to admit he had not seen Despard for the last twenty years. Other military leaders also spoke about Despard's good service.

In the end, the jury found Despard guilty of only one clear act: giving illegal oaths. But they asked for mercy, perhaps moved by Nelson's testimony. The judge, Lord Ellenborough, refused their request. He said Despard's goal was to break the new union between Great Britain and Ireland and to make everyone equal in terms of property and rights.

Despard and six other men were sentenced to be hanged, drawn and quartered.

Aftermath

Catherine Despard's last act for her husband was to insist that he be buried in St Faith's in the City of London. This was an old graveyard inside St Paul's Cathedral. She won this right despite protests from the government. On the day of the funeral, March 1, people lined the streets from their home to St Paul's.

After Edward's death, there was a report that Catherine Despard was taken care of by Lady Nelson. A Member of Parliament, Sir Francis Burdett, helped her get a pension. She spent some time in Ireland as a guest of Valentine Lawless, 2nd Baron Cloncurry, who had been imprisoned with Despard. Catherine Despard died in Somers Town, London, in 1815.

Their son, James, returned to Britain after the Napoleonic Wars. The last mention of him in family records is when Edward's older brother, General John Despard, saw a carriage driver calling the family name. He saw "a flashy Creole and a flashy young lady on his arm" get into the carriage.

|

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |