Mosquito Coast facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Mosquito Coast

Miskitu Nation

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early 17th century–1894 | |||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Status |

|

||||||||

| Capital |

|

||||||||

| Common languages |

|

||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

| King | |||||||||

|

• c. 1650–1687

|

Oldman (first known) | ||||||||

|

• 1842–1860

|

George Augustus Frederic II (last) | ||||||||

| Hereditary Chief | |||||||||

|

• 1860–1865

|

George Augustus Frederic II (first) | ||||||||

|

• 1890–1894

|

Robert Henry Clarence (last) | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

|

• Established

|

Early 17th century | ||||||||

|

• Disestablished

|

20 November 1894 | ||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||

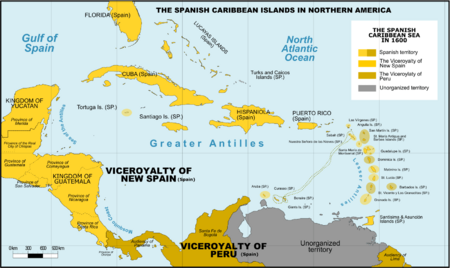

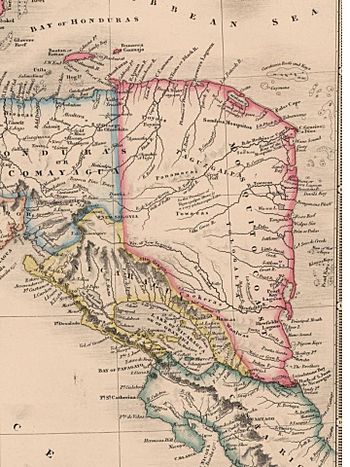

The Mosquito Coast (also known as the Mosquitia or Mosquito Shore) is a coastal area in Central America. It stretches along the eastern parts of what are now Nicaragua and Honduras. This region was named after the local Miskito Nation. For a long time, it was strongly influenced by the British and was known as the Mosquito Kingdom.

In 1860, control of the area was given to Nicaragua, and it was called the Mosquito Reserve. By November 1894, Nicaragua fully took over the Mosquito Coast. Later, in 1960, the northern part of the region was given to Honduras by the International Court of Justice. The Mosquito Coast was usually seen as the land ruled by the Miskito Kingdom. Its size changed as the kingdom grew or shrank.

Contents

- History of the Mosquito Coast

- Miskito Kings and Chiefs

- Who Lives There Now?

- Religion

- In Popular Culture

- See also

History of the Mosquito Coast

Before Europeans arrived, the area had many small groups of people. They lived in a way where everyone was mostly equal. Columbus briefly visited the coast during his fourth voyage. Spanish records about the region only started appearing in the late 1500s and early 1600s.

Early Spanish Attempts to Settle

During the 1500s, Spanish leaders tried several times to conquer the region. However, there is no proof that they ever managed to set up lasting settlements. The Spanish could not conquer this area. In the 1600s, they tried to bring the local people under their control through missionaries. These efforts also failed to have any lasting success.

Because the Spanish did not have much power in the region, it stayed independent. This allowed the native people to continue their traditional way of life. It also allowed them to welcome visitors from other places. English and Dutch privateers (like legal pirates) who attacked Spanish ships often found a safe place on the Mosquito Coast.

British Contact and the Miskito Kingdom

|

Mosquito Kingdom

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1638–1787 | |||||||||||

|

Flag

|

|||||||||||

|

Anthem: God Save the King (1745–1787)

|

|||||||||||

| Status |

|

||||||||||

| Capital | Sandy Bay (King's residence) |

||||||||||

| Common languages |

|

||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||

| Monarch | |||||||||||

|

• c. 1650–1687

|

Oldman (first known) |

||||||||||

|

• 1776–1801

|

George II Frederic (last) |

||||||||||

| Superintendent of the Shore | |||||||||||

|

• 1749–1759

|

Robert Hodgson, Sr. (first) | ||||||||||

|

• 1775–1787

|

James Lawrie (last) | ||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||

|

• Arrival of the Providence Island Company

|

1630 | ||||||||||

|

• British ally

|

1638 | ||||||||||

| 1740 | |||||||||||

| 1786 | |||||||||||

|

• British evacuation

|

1787 | ||||||||||

| Currency | Pound sterling | ||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

In the early 1600s, a political group existed on the coast that the English called the "Mosquito Kingdom." One of its kings visited England around 1638 and formed an alliance. This kingdom strongly resisted any Spanish attacks. It also offered safety to any groups that were against Spain. English and French privateers and pirates often visited to get water and food.

Early British Alliance

British contact with the Mosquito region began around 1630. Agents from the English Providence Island Company made friends with the local people. The company's main base, Providence Island, regularly communicated with the coast.

The Providence Island Company helped the Miskito "King's Son" visit England. When his father died, this son returned home and put his country under English protection. After Spain captured Providence Island in 1641, England did not have a nearby base. However, after England captured Jamaica in 1655, they restarted relations. The Miskito leader Oldman visited England. His son later said that Oldman met with King Charles II.

The Miskito Sambu People

The Miskito Sambu people are believed to be descendants of shipwrecked slaves. These slaves arrived in the mid-1600s and married local Miskito people. They slowly adopted the Miskito language and culture. The Miskito Sambu settled near the Wanks (Coco) River. By the late 1600s, their leader was a general in charge of the northern parts of the Mosquito Kingdom. In the early 1700s, they took over the role of King.

In the late 1600s and early 1700s, Miskito Sambu began raiding Spanish territories. They also attacked other independent native groups. Miskito raiders traveled as far north as Yucatán and as far south as Costa Rica. They sold many of the people they captured as slaves to British merchants. These slaves were sent to Jamaica to work on sugar plantations.

How the Kingdom Was Organized

Even though the English called it a "kingdom," it was not very strictly organized. A description from 1699 said that the kingdom covered different areas along the coast. It probably did not include all English trading settlements. The Miskito social structure was not very strict. People with titles like "king" or "governor" were mainly war leaders. They did not have the final say in legal problems. The author of the 1699 description saw the people living in a mostly equal way.

Later, sources defined the main offices as king, a governor, and a general. In the early 1700s, the Miskito kingdom was divided into four main groups of people. These groups lived along the banks of rivers. They were part of one political group, though it was loosely connected. The northern parts were mostly ruled by Sambus. The southern parts were ruled by Tawira Miskitos.

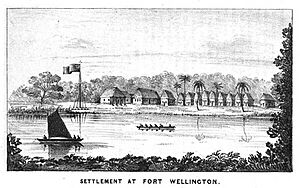

British Settlements

The Miskito king Edward I and the British signed a formal Treaty of Friendship and Alliance in 1740. Robert Hodgson, Senior, was made Superintendent of the Shore. This treaty meant that the British had a strong influence over the Mosquito Kingdom.

The main reason for the treaty was to create an alliance between the Miskito and British. This was for the War of Jenkins' Ear. The Miskito and British worked together to attack Spanish settlements during the war. This military teamwork was important for protecting British interests.

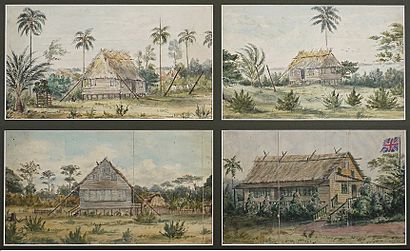

A lasting result of this relationship was that King Edward I allowed the British to set up settlements and farms. The British mainly settled in the Black River area, Cape Gracias a Dios, and Bluefields. British farmers grew crops for export and harvested timber, especially mahogany. Most of the work was done by African slaves and native slaves. By 1786, there were hundreds of British residents and thousands of slaves. The Miskito kings received gifts from the British, like weapons and goods. They also helped keep the peace and catch runaway slaves.

British Leave the Coast

Spain, which claimed the territory, suffered a lot from Miskito attacks. These attacks continued even during peacetime. When the American Revolutionary War began, Spanish forces tried to remove the British. They took the settlement at Black River. However, this failed when armed settlers, led by Edward Despard, took the settlements back.

Even though Spain could not drive the British out, Britain made agreements with Spain. In the 1786 Convention of London, Britain agreed to move British settlers and their slaves from the Mosquito Coast. They moved them to what would become British Honduras (now Belize). Some settlers and their slaves stayed after promising loyalty to the King of Spain, especially in Bluefields.

Spanish Influence and Miskito Resistance

The Mosquito Coast was first added to the Captaincy General of Guatemala. However, it was hard to communicate with Guatemala City. So, Miskito leaders found it easier to sail to Cartagena de Indias and promise loyalty to Spain there. The Spanish hoped to gain the Miskito leaders' support by offering gifts, just like the British had. They also educated Miskito youth in Guatemala. Catholic missionaries also came to the Coast to convert the native people.

The Miskito did not all accept the new Spanish rule equally. Some Miskito leaders, especially in the northern areas, remained friendly with the British. Others, in the south, became closer to Spain. The Spanish also tried to bring their own settlers to the area. Starting in 1787, about 1,200 settlers came from Spain. They settled in Sandy Bay, Cape Gracias a Dios, and Black River.

Miskito Revolt

The new Spanish colony faced problems. Many settlers died on the way. The Miskito leaders were not happy with the gifts from the Spanish. The Miskito restarted trade with Jamaica. When news of another war between Britain and Spain arrived in 1797, King George II raised an army. They attacked Bluefields, removed the Spanish governor, and drove the Spanish out on September 4, 1800. However, the king died suddenly in 1801. Many believed he was poisoned.

With Spanish power gone and British influence returning, the Captaincy General of Guatemala wanted full control of the coast. However, the Spanish government decided against this. On November 30, 1803, they gave control of the Mosquito Coast to the Viceroyalty of New Granada. This decision later caused land disputes between new independent countries in Central and South America.

Meanwhile, King George II's brother, Stephen, tried to make deals with Spain. Spain called him king and gave him gifts. But he later changed his mind and raided Spanish territory. In 1815, Stephen and other Miskito leaders officially recognized George Frederic Augustus I as their new king. His coronation in Belize in 1816 showed strong British support. Spain lost control over New Granada in 1819 and Central America in 1821.

British Influence Returns

After independence, new countries in Central and South America faced their own problems. This meant they could not threaten the Miskito kingdom. Miskito Kings renewed their alliance with Great Britain. Belize became the main British connection to the kingdom.

Growing Economy

The Miskito kings allowed foreigners to settle in their lands. British merchants and Garifuna people from Honduras took this chance. Between 1820 and 1837, a Scottish trickster named Gregor MacGregor pretended to be a Miskito chief. He sold fake land rights to settlers in Britain and France. Most settlers died from diseases because the area was not developed as he claimed.

At the same time, the demand for mahogany wood grew in Europe. Belize, a major exporter, was running out. The Miskito Kingdom became a new source for wood. British companies got permission to cut wood there. In 1837, Britain officially recognized the Mosquito Kingdom as an independent state. They worked to stop new Central American nations from interfering with the kingdom.

The growing economy attracted money from the United States. Immigrants also came from the US, the West Indies, Europe, Syria, and China. Many Afro-Caribbean people arrived after slavery was ended in British and French colonies in 1841. They settled mainly around Bluefields. These people, mixed with descendants of earlier slaves, formed the Miskito Coast Creoles. Because they knew English well, Creoles were often hired by foreign companies.

In 1841, a British ship, without London's knowledge, helped the Miskito King Robert Charles Frederic and the British Governor of Belize take over Nicaragua's only Caribbean port, San Juan del Norte. This port was important for a possible future canal across Nicaragua. The Nicaraguan government protested, but the British did not punish their governor.

Second British Protectorate and US Opposition

|

Miskito Kingdom

|

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1844–1860 | |||||||||||||

|

Anthem: God Save the Queen

|

|||||||||||||

| Status | Protectorate of the United Kingdom | ||||||||||||

| Capital | Bluefields | ||||||||||||

| Common languages | English Miskito |

||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||

| King | |||||||||||||

|

• 1842–1860

|

George Augustus Frederic II | ||||||||||||

| Consul-General Consul (after 1851) |

|||||||||||||

|

• 1844–1848

|

Patrick Walker (first) | ||||||||||||

|

• 1849–1860

|

James Green (last) | ||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||

|

• Protectorate declared

|

1844 | ||||||||||||

|

• Annexation of San Juan del Norte

|

1848 | ||||||||||||

| 1854 | |||||||||||||

|

• Treaty of Managua

|

January 28 1860 | ||||||||||||

| Currency | Pound sterling | ||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

In 1844, the British government declared a new protectorate over the Mosquito Kingdom. They appointed Patrick Walker as consul-general in Bluefields. This was partly because of the disorder in the Mosquito Kingdom. It was also because Britain wanted to build a canal through Central America before the United States.

The British claimed the protectorate stretched from Cape Honduras to the San Juan River. This included San Juan del Norte. Nicaragua protested and sent forces there. The Miskito King George Augustus Frederic II demanded all Nicaraguan forces leave. Nicaragua asked the United States for help, but the US was busy with the Mexican–American War. After the deadline, Miskito-British forces, backed by two British warships, took San Juan del Norte. Nicaragua then signed a peace treaty, giving San Juan del Norte to the Mosquito Kingdom. It was renamed Greytown.

After the Mexican-American War, the US tried to unite Nicaragua, El Salvador, and Honduras against the British. In 1850, Britain and the US signed the Clayton–Bulwer Treaty. They promised to keep any future canal neutral and not to take control of Nicaragua, Costa Rica, or the Mosquito Coast. The US thought this meant Britain would leave the Mosquito Coast immediately. Britain argued it only meant they would not expand further.

More problems happened in the following years. In 1852, Britain took the Bay Islands off Honduras. In 1854, an American ship captain killed a local in Greytown. An American official, Solon Borland, stopped the arrest. He argued that they could not arrest an American citizen. Borland ordered American passengers to stay and "protect US interests." The Americans sent a warship and demanded money and an apology. When their demands were not met, the ship bombarded Greytown. Then, sailors landed and burned the town. No one was killed, but the damage was huge. Britain, busy with the Crimean War, only protested.

By 1859, British people no longer supported their country's presence on the Mosquito Coast. The British government returned the Bay Islands and gave the northern part of the Mosquito Coast to Honduras. The next year, Britain signed the Treaty of Managua. This treaty gave the rest of the Mosquito Coast to Nicaragua.

Arrival of the Moravian Church

In the 1840s, two British citizens advertised land sales in Cabo Gracias a Dios. This interested Prince Charles of Prussia. He first wanted to set up a Prussian settlement. Later, he suggested sending missionaries. The Moravian Church took on this task. The first missionaries arrived in 1848 and began working in 1849 in Bluefields. They focused on the royal family and the Creoles. By 1890, the church had many members, mostly Miskito and rural natives.

Treaty of Managua and Autonomy

|

Mosquito Reserve

Reserva Mosquitia

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1860–1894 | |||||||||

|

Anthem: Hermosa Soberana

|

|||||||||

| Status | Autonomous territory of Nicaragua | ||||||||

| Capital | Bluefields | ||||||||

| Common languages | Miskito English Mayangna |

||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

| Hereditary Chief | |||||||||

|

• 1860-1865

|

George Augustus Frederic II (first) | ||||||||

|

• 1890-1894

|

Robert Henry Clarence (last) | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

|

• Treaty of Managua

|

January 28 1860 | ||||||||

|

• Annexation to Nicaragua

|

20 November 1894 | ||||||||

| Currency | Nicaraguan peso Pound sterling |

||||||||

|

|||||||||

Britain and Nicaragua signed the Treaty of Managua on January 28, 1860. This treaty gave control over the Caribbean coast between Cabo Gracias a Dios and Greytown to Nicaragua. The treaty also said that the Mosquito Kingdom, now smaller and around Bluefields, would become an autonomous Miskito reserve. It was usually called the Mosquito Reservation or Mosquito Reserve.

The reserve's constitution, signed in 1861, confirmed George Augustus Frederic II as the ruler. But he was now called a hereditary chief, not a king. The chief would be advised by a council of 41 members. This council was not only for Miskito people. The first council included Moravian missionaries. Nicaragua agreed to pay George Augustus Frederic II £1000 yearly until 1870.

When George Augustus Frederic II died in 1865, a dispute arose. The council argued that none of his children could be chief because their mothers were not Miskito. They elected William Henry Clarence, George Augustus Frederic II's nephew, as the new chief. Nicaragua did not recognize this election. William Henry Clarence asked Britain for support. He accused Nicaragua of not following the 1860 treaty and threatening Miskito autonomy.

In 1881, Nicaragua and Britain agreed to let Emperor Francis Joseph I of Austria-Hungary decide on the disputed parts of the 1860 treaty. His decision, released in 1881, mostly favored the Miskito and the British. It stated that:

- Nicaragua had control over the Mosquito Coast, but the Miskito had a lot of self-rule.

- Nicaragua could fly its flag anywhere on the Mosquito Coast.

- Nicaragua could have a representative on the Mosquito Coast.

- The Miskito could also fly their own flag, but it had to show Nicaraguan control.

- Nicaragua could not make deals for natural resources in the Mosquito Coast. Only the Miskito government could do that.

- Nicaragua could not control Miskito trade or tax imports/exports.

- Nicaragua had to pay the money owed to the Miskito chief.

- Nicaragua could not limit goods imported or exported through San Juan del Norte (Greytown).

Annexation by Nicaragua

In 1894, Rigoberto Cabezas led a campaign to fully add the reserve to Nicaragua. The native people strongly protested and asked Britain for help, but it was too late. From July 6 to August 7, the US military occupied Bluefields to 'protect US interests'. On November 20, 1894, the territory officially became part of Nicaragua. It was named the Nicaraguan department of Zelaya. In the 1980s, this department was divided into two autonomous regions. These regions were renamed the North Caribbean Coast Autonomous Region (RACCN) and the South Caribbean Coast Autonomous Region (RACCS) in 2014.

Miskito Under Nicaragua

The Miskito people kept some self-rule under Nicaragua. However, there was often tension between the government and the native people. This tension was clear during the Sandinista rule, which wanted more state control. The Miskito strongly supported US efforts against the Sandinistas. They were important allies of the Contras.

Miskito Separatism

Some Miskito people declared the independence of the Communitarian Nation of Moskitia in 2009. This movement is led by Reverend Hector Williams. He was chosen as "Wihta Tara" (Great Judge) by the Council of Elders. This council is made up of traditional Miskito leaders. The council wants independence and has thought about holding a vote.

Miskito Kings and Chiefs

- c. 1650–c. 1687 Oldman

- c. 1687–1718 Jeremy I

- 1718–1729 H.M. Jeremy II

- 1729–1755 H.M. Edward I

- 1755–1776 H.M. George I

- 1776–1800 H.M. George II Frederic

- 1800–1824 H.M. George Frederic Augustus I

- 1824–1841 H.M. Robert Charles Frederic

- 1841–1865 H.M. George Augustus Frederic II

- 1865–1879 H.E. William Henry Clarence, Hereditary Chief of Miskito

- 1879–1888 H.E. George William Albert Hendy, Hereditary Chief of Miskito

- 1888–1889 H.E. Andrew Hendy, Hereditary Chief of Miskito

- 1889–1890 H.E. Jonathan Charles Frederick, Hereditary Chief of Miskito

- 1890–1905 H.E. Robert Henry Clarence, Hereditary Chief of Miskito

Who Lives There Now?

The Mosquito Coast used to be a very sparsely populated area. Today, the part of the Miskito Coast in Nicaragua has about 400,000 people. These include:

- 57% Miskito

- 22% Creoles (people of African and European descent)

- 15% Ladinos (people of mixed European and Indigenous descent)

- 4% Sumu (Native American)

- 1% Garifuna (people of African and Indigenous descent)

- 0.5% Chinese

- 0.5% Rama (Native American)

Religion

Anglicanism and the Moravian Church became very popular on the Mosquito Coast.

In Popular Culture

- W. Douglas Burden wrote about an expedition looking for a silver mine along the coast in his book Look to the Wilderness.

See also

In Spanish: Costa Mosquito para niños

In Spanish: Costa Mosquito para niños

- Garifuna people

- Miskito

- La Mosquitia

- The Mosquito Coast - a 1986 US movie