Arthur O'Connor (United Irishman) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Arthur O'Connor

|

|

|---|---|

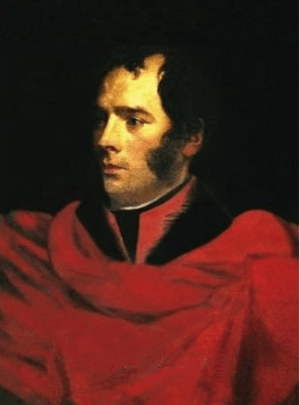

O'Connor in French military uniform

|

|

| Member of Parliament for Philipstown | |

| In office 1790–1795 |

|

| Preceded by | John Toler Henry Cope |

| Succeeded by | William Sankey John Longfield |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 4 July 1763 Bandon, County Cork |

| Died | 25 April 1852 (aged 88) |

| Spouse |

Alexandrine Louise Sophie de Caritat de Condorcet

(m. 1807) |

| Relations | Roger O'Connor (brother) |

| Children | 5, including Daniel |

Arthur O'Connor (born July 4, 1763 – died April 25, 1852) was an important Irish leader. He was part of a group called the Society of United Irishmen. This group wanted to make Ireland a more fair and independent country. Arthur O'Connor worked hard to find friends for Ireland in England and France. He believed in strong democratic changes. He was also known for writing messages to women about politics.

He was arrested just before the Irish Rebellion of 1798 started. In 1802, he moved to France. There, he became a General in a French army that planned to invade Ireland. But he later had disagreements with Napoleon. In his later years, he supported the July Revolution in Paris. He also disagreed with Daniel O'Connell's movement in Ireland, which he felt was too focused on the church.

Contents

Arthur O'Connor's Early Life

Arthur O'Connor was born on July 4, 1763, near Bandon, County Cork, in Ireland. His family was wealthy and Protestant. His brother, Roger O'Connor, shared his ideas about a republic. Arthur was also an uncle to several notable people, including Feargus O'Connor. However, two of his other brothers, Daniel and Robert, supported the British.

Arthur studied law at Trinity College Dublin. He became a lawyer in 1788. But he inherited a lot of money, so he never actually worked as a lawyer.

Joining the United Irishmen

From 1790 to 1795, Arthur O'Connor was a Member of Parliament for Philipstown. He joined a group of politicians who wanted to help the Catholic majority in Ireland. They also wanted other important changes.

At first, he was part of important social clubs. But this did not last long. In 1796, O'Connor joined the Society of United Irishmen. This group wanted to change the way Ireland was ruled. They wanted a government that represented everyone. They also wanted Ireland to be independent from London.

In 1797, O'Connor tried to win a seat in Parliament for County Antrim. He told voters he wanted to end religious differences. He also wanted a national government. He spoke out against British and Scottish troops in Ireland. He also opposed the war with France. He was arrested in February for speaking out too strongly. He explained that the government made it hard to have fair elections. With other United Irish leaders, he started looking for help from France.

He called for a "representative democracy." This meant a government chosen by all people. He wanted to break all "monopolies," which meant unfair control over property or religion.

Speaking to the Women of Ireland

In London, Arthur O'Connor met with other radical thinkers. This included Jane Greg, who was also a United Irish supporter. Jane Greg was very active in women's United Irish groups in Belfast. Arthur O'Connor himself wrote messages to women about politics.

After a newspaper called the Northern Star was shut down, O'Connor helped start a new paper called the Press in Dublin. In December 1797, he wrote an article for the paper. He encouraged women to get involved in the political changes happening in Ireland. He told them that young men now respected women's ideas. He said that only "brainless" people would dislike the idea of a woman in politics.

In February 1798, O'Connor's paper published another message. It made it clear that women were seen as important thinkers in public discussions.

Arrest and Time in Prison

In March 1798, Arthur O'Connor was traveling to France. He was arrested with a Catholic priest named James Coigly and two other United Irishmen. Coigly was found with secret papers and faced serious charges. O'Connor was able to have important people like Charles James Fox speak for him. He was found not guilty. However, he was immediately arrested again and put in prison.

O'Connor was held at Fort George in Scotland. Other United Irish leaders were also there. He often argued with them. He did not get along well with people like Thomas Addis Emmet.

Life in France

In 1802, O'Connor was released from prison. But he was sent away from Ireland. He went to Paris, France. There, Napoleon saw him as the main representative of the United Irishmen. In 1804, Napoleon made him a General. He was to lead an Irish Legion that was preparing to invade Ireland. However, O'Connor's honest and freedom-loving nature did not always please Napoleon. After Napoleon stopped his plans for Ireland, he did not use O'Connor in military roles again. Also, O'Connor had no military experience. So, many Irish soldiers in the Legion did not like his appointment.

Robert Emmet did not trust O'Connor to share his plans for another uprising in Ireland. When Britain and France started fighting again in 1803, Emmet sent his own messenger to Paris. He asked for money, weapons, and officers. He did not want a large number of troops, as O'Connor had suggested. After his uprising in Dublin failed, Emmet asked another rebel, Myles Byrne, to ask France for help.

After Napoleon's final defeat, O'Connor became a French citizen. He supported the July Revolution in 1830. This revolution removed King Charles X from power. O'Connor wrote a public letter supporting the events to General Lafayette. After the revolution, he became the mayor of Le Bignon-Mirabeau. He also edited a newspaper about religious ideas. He wrote several books about politics and society. He also helped his wife and her mother, Sophie de Condorcet, prepare a new edition of his father-in-law's works.

In 1834, O'Connor was allowed to visit Ireland with his wife. He went to sell his properties there. At this time, Daniel O'Connell was leading a movement to end the Acts of Union 1800. O'Connor did not like O'Connell's movement. He felt it relied too much on the Catholic clergy. In his last book, Monopoly: The Cause of all Evil (1848), he criticized O'Connell. He said O'Connell and his priests were undoing the work of the United Irishmen. He believed they were stopping "union, love [and] fraternity" among Irish people.

Arthur O'Connor's Family Life

In 1807, Arthur O'Connor married Alexandrine Louise Sophie de Caritat de Condorcet. She was known as Eliza. She was the daughter of a famous French thinker, the Marquis de Condorcet. She was also the daughter of the well-known hostess, Sophie de Condorcet. Arthur was more than twice her age.

Arthur and Eliza had five children. They had three sons and two daughters. Sadly, almost all of them died before Arthur did. Only one son, Daniel, got married and had children.

- Daniel O'Connor (1810–1851) married Ernestine Duval du Fraville in 1843.

Arthur O'Connor died on April 25, 1852. His wife, Eliza, died in 1859.

His Descendants

Arthur O'Connor's descendants continued to serve as officers in the French army. They still live at Château du Bignon. Through his son Daniel, he had two grandsons:

- Arthur O'Connor (1844–1909) served in the French army.

- Fernand O'Connor (1847–1905) was a Brigade General. He served in Africa and became a Knight of the Legion of Honour.

His grandson, Arthur, married Marguerite de Ganay in 1878. They had two daughters: Elisabeth O’Connor and Brigitte Emilie Fernande O'Connor. Brigitte married Comte François de La Tour du Pin in 1904. He was killed ten years later at the First Battle of the Marne.

See Also

| Shirley Ann Jackson |

| Garett Morgan |

| J. Ernest Wilkins Jr. |

| Elijah McCoy |