Leonard McNally facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Leonard McNally

|

|

|---|---|

Leo. MacNally Esq.

|

|

| Born | 27 September 1752 |

| Died | 13 February 1820 (aged 68) Dublin, United Kingdom

|

| Burial place | Donnybrook, County Dublin, Ireland |

| Spouse(s) |

Mary O'Brien

(m. 1784; d. 1786)Frances l'Anson

(m. 1787; d. 1795)Louisa Edgeworth

(m. 1799) |

Leonard McNally or MacNally (September 27, 1752 – February 13, 1820) was a very interesting person from Ireland. He was a barrister (a type of lawyer), a writer of plays and songs, and a founding member of a group called the United Irishmen. However, he was also secretly a spy for the British government.

McNally was a successful lawyer in Dublin in the late 1700s and early 1800s. He even wrote an important law book. But many people knew him best for his popular plays and his famous romantic song, "The Lass of Richmond Hill". Today, he is mostly remembered as a key informer for the British government. He played a big part in stopping the Irish Rebellion of 1798. He would get paid by the government to betray his friends in the United Irishmen. Then, when he defended them in court, he would secretly help the prosecution (the lawyers trying to prove guilt) to make sure they were found guilty. Some of his famous clients included Napper Tandy, Wolfe Tone, Robert Emmet, and Lord Edward FitzGerald.

Contents

Early Life and Education

McNally was born in Dublin in 1752. His father was a merchant who imported wine. Leonard was raised by his mother and his uncle. His family was Roman Catholic, but in the 1760s, he changed his religion to the Church of Ireland.

He loved theatre and taught himself a lot about it. At first, he worked as a merchant in Bordeaux, France, like his father. But in 1774, he moved to London to study law. He became a lawyer in Ireland in 1776. Later, in 1783, he also qualified as a lawyer in England. While in London, he earned extra money by writing plays and editing a newspaper called The Public Ledger.

McNally's Career

A Lawyer for Change

After returning to Ireland, McNally became a very successful lawyer in Dublin. He became an expert in the law of evidence, which deals with what information can be used in court. In 1802, he published a widely used textbook called The Rules of Evidence on Pleas of the Crown. This book was very important in establishing the idea of "beyond reasonable doubt" for criminal trials. This means that for someone to be found guilty, there must be no reasonable doubt about their guilt.

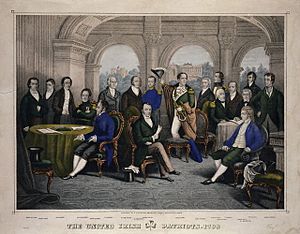

Soon after returning to Ireland, he became involved in politics that wanted big changes. In 1782, he wrote a pamphlet supporting the Irish cause. He became Dublin's main lawyer for radical groups. In 1792, he represented Napper Tandy, a politician, in a legal case. In the early 1790s, McNally helped start the United Irishmen. This was a secret group that soon became a revolutionary organization fighting for Irish independence. He was a high-ranking leader and the group's main lawyer. He defended many United Irishmen in court, including Wolfe Tone and Robert Emmet, who led rebellions in 1798 and 1803.

In 1793, McNally was hurt in a duel (a fight with weapons) with Sir Jonah Barrington. Barrington had insulted the United Irishmen. Later, Barrington described McNally as "a good-natured, hospitable, talented and dirty fellow." Another writer, John O'Keeffe, said McNally had "a handsome, expressive countenance and alive sparkling eyes."

The Secret Spy

After McNally died in 1820, people found out that he had been a secret informer for the government for many years. He was one of the most successful British spies in Irish revolutionary groups. In 1794, the British government discovered that the United Irishmen were planning to ask for help from Revolutionary France. McNally became an informer to save himself. After that, he also received payments for his spying. From 1794 until his death in 1820, McNally was paid an annual pension of £300 for his work as an informer.

From 1794 onwards, McNally regularly gave information about his United Irishmen friends to the authorities. These friends often met at his house. It was McNally who betrayed Lord Edward FitzGerald, a leader of the 1798 rebellion, and Robert Emmet in 1803. A big reason why the 1798 rebellion failed was because the government received very good information from its spies. McNally was considered one of the most damaging informers.

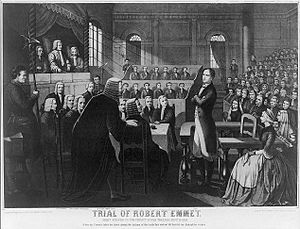

The United Irishmen McNally defended in court were almost always found guilty. McNally was paid by the government for sharing the secrets of their defense with the prosecution. For example, during Emmet's trial, McNally gave details of the defense strategy to the government. He also handled his client's case in a way that helped the prosecution. Three days before the trial, he told the authorities that Emmet "does not intend to call a single witness." For helping the prosecution in Emmet's case, he received an extra £200, on top of his pension. Half of this was paid five days before the trial.

After McNally's death, his secret life as a government agent became known. This happened when his heir (the person who inherited his money) tried to keep collecting his £300 yearly pension. Many Irish nationalists still remember him with great anger. In 1997, the Sinn Féin newspaper, An Phoblacht, wrote an article about McNally. It called him "undoubtedly one of the most treacherous informers of Irish history."

A Talented Writer

McNally was a successful writer of plays. He wrote several well-made comedies and comic operas (plays with singing). His first play was The Ruling Passion, a comic opera from 1771. He wrote at least twelve plays between 1779 and 1796, as well as other comic operas. His works include The Apotheosis of Punch (1779), which made fun of the Irish playwright Richard Brinsley Sheridan. He also wrote Tristram Shandy (1783), which was based on Lawrence Sterne's novel. Other plays were Robin Hood (1784), Fashionable Levities (1785), Richard Cœur de Lion (1786), and Critic Upon Critic (1788).

He also wrote many songs and operettas for the Covent Garden theatre in London. One of his songs, Sweet Lass of Richmond Hill, became very famous and popular. It was first performed publicly at Vauxhall Gardens in London in 1789. People said it was a favorite song of George III, the King of England. The song helped make the romantic phrase "a rose without a thorn" popular, which McNally had used in the song.

Personal Life

Not much is known about McNally's first wife, Mary O'Brien, except that she died in 1786. In London in 1787, McNally ran away with Frances I'Anson. Her father, William I'Anson, who was a lawyer, did not approve of McNally. Frances and her family's home, Hill House in Richmond, Yorkshire, were the inspiration for the song "Sweet Lass of Richmond Hill". McNally wrote the lyrics, and James Hook composed the music. In 1795, Frances died during childbirth at age 29. She left behind only one daughter. In 1799, McNally married his third wife, Louisa Edgeworth. She was the daughter of a clergyman from County Longford. With Louisa, he had at least three sons.

When his son, who was also a lawyer, died on February 13, 1820, many newspapers mistakenly reported that it was Leonard McNally himself who had died. His son was buried in Donnybrook, Dublin on February 17, 1820. On March 6, 1820, McNally sent a letter from his home in Dublin to the owner of 'Saunders's Newsletter'. He asked for money because the false news of his death had caused him serious harm. In June 1820, McNally was dying. Even though he had been a Protestant for most of his adult life, he asked a Roman Catholic priest for forgiveness. He was also buried in Donnybrook on June 8, 1820.

| Stephanie Wilson |

| Charles Bolden |

| Ronald McNair |

| Frederick D. Gregory |