History of the Acadians facts for kids

The Acadians (pronounced Ah-KAY-dee-ens) are people whose families came from France in the 1600s and 1700s. They settled in a part of North America called Acadia. This area is now mostly the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island. It also included parts of eastern Québec and southern Maine.

Most of these early French settlers came from the southwestern and southern parts of France. Some Acadians also have ancestors from the Indigenous peoples of the region. Today, because people have mixed over time, some Acadians also have other family backgrounds.

Acadia's history was greatly shaped by six wars between the French and British in the 1600s and 1700s. The last of these wars, the French and Indian War, led to the British forcing many Acadians to leave their homes. This event is known as the Expulsion of the Acadians. After the war, many Acadians returned to Acadia or came out of hiding. Others stayed in France, and some moved to Louisiana in the United States. There, they became known as Cajuns, a name that comes from "Acadiens."

The 1800s saw the start of the Acadian Renaissance, a time when Acadian culture became stronger. A famous poem called Evangeline was published, which helped bring Acadians together. In the last century, Acadians have worked hard to gain equal language and cultural rights as a minority group in Canada's Maritime Provinces.

Contents

Early French Settlers in Acadia

Building Port Royal (1604-1613)

Pierre Dugua, Sieur de Monts built the Habitation at Port-Royal in 1605. This was a new settlement after his first try at Saint Croix Island didn't work out. In 1607, de Monts' trading rights were taken away, and most French settlers went back to France. However, some stayed behind. Jean de Biencourt de Poutrincourt et de Saint-Just led another group to Port Royal in 1610.

First European Families Arrive

The Acadian settlements survived because they worked well with the Indigenous peoples. In the early years, some Acadians married Indigenous women. For example, Charles La Tour married a Mi'kmaw woman in 1626. Some Acadians also married Indigenous spouses in the local way and lived in Mi'kmaq communities. French wives also came to Acadia, like La Tour's second wife, Françoise-Marie Jacquelin, who arrived in 1640.

Governor Isaac de Razilly helped prepare for the first families to arrive. They sailed on the ship Saint Jehan from France on April 1, 1636. This ship's detailed passenger list is the only one that survived from that time. After 35 days, the Saint Jehan arrived on May 6, 1636, at LaHave, Nova Scotia. There were 78 passengers and 18 crew members.

With this ship, Acadia slowly changed from a place for explorers and traders to a colony with permanent settlers, including women and children. By the end of 1636, the settlers moved from LaHave to Port Royal. There, Pierre Martin and Catherine Vigneau, who came on the Saint Jehan, had the first European child born in Acadia, Mathieu Martin. Because of this, Mathieu Martin later became an important leader in Cobequid in 1699.

Historians believe that the settlers from the Vienne and Aquitaine regions of France brought their customs to Acadia. They were used to living on the frontier and spread out their settlements based on family ties. They were good at farming and trading. A unique Acadian identity grew from mixing traditional French ways with the methods and ideas of the Indigenous peoples of North America.

Acadia's Civil War (1640–1645)

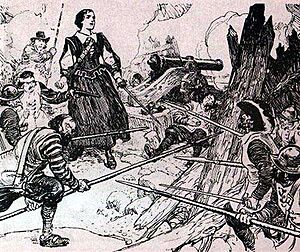

After Governor Isaac de Razilly died, Acadia faced a civil war from 1640 to 1645. There were two main leaders: Governor Charles de Menou d'Aulnay de Charnisay at Port Royal and Governor Charles de Saint-Étienne de la Tour in what is now Saint John, New Brunswick.

There were four main battles during this war. La Tour attacked d'Aulnay at Port Royal in 1640. D'Aulnay then blocked La Tour's fort at Saint John for five months, but La Tour won. La Tour attacked Port Royal again in 1643. Finally, d'Aulnay and Port Royal won the war with the siege of Saint John in 1645. After d'Aulnay died in 1650, La Tour returned to power in Acadia.

English Control (1654–1667)

In 1654, war broke out between France and England. A group of ships from Boston, sent by Oliver Cromwell, came to Acadia to remove the French. They captured La Tour's fort and then Port-Royal. La Tour went to England and, with help, managed to get part of Acadia back from Cromwell. He returned to Cap-de-Sable and stayed there until he died in 1666.

During the time England controlled Acadia, France's minister, Jean-Baptiste Colbert, told Acadians not to return to France. Because of this English control, no new French families settled in Acadia between 1654 and 1670.

Acadia Returns to France

The Treaty of Breda (1667), signed in 1667, gave Acadia back to France. A year later, Marillon du Bourg arrived to claim the land for France. Alexandre LeBorgne, the son of LeBorgne, became the temporary governor. He married Marie Motin-La Tour, the oldest child of La Tour and d'Aulnay's widow.

In 1670, the new governor, Hubert d'Andigny, took the first census in Acadia. It showed about sixty Acadian families with around 300 people. These people mostly farmed using special dykes called aboiteaus along the shores of the Bay of Fundy. There were no major efforts to increase Acadia's population.

In 1671, more than fifty colonists arrived from France. Others came from Canada (New France) or were retired soldiers. During this time, some colonists married local First Nations people. For example, the commander at Pentagoet, Vincent de Saint-Castin, married Marie Pidikiwamiska, the daughter of an Abenakis chief.

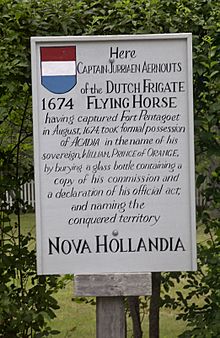

In 1674, the Dutch briefly took over Acadia and renamed it New Holland.

In the late 1600s, Acadians moved from the capital, Port Royal, and started other important settlements. These included Grand Pré, Chignecto, Cobequid, and Pisiguit. These places became major Acadian communities before the Expulsion.

Life for settlers on Ile St.-Jean (now Prince Edward Island) was very hard before the expulsion. Good harvests were often followed by crop failures. Fires sometimes destroyed crops, animals, and farms. Famine and starvation were common, and people often begged for supplies from other places. In 1756, a famine on Ile St.-Jean caused some families to move to Québec.

Before Halifax was founded in 1749, Port Royal (later Annapolis Royal) was the capital of Acadia and Nova Scotia for most of 150 years. The British tried six times to conquer Acadia by taking the capital. They finally succeeded in the Siege of Port Royal (1710). For the next fifty years, the French and their allies tried six times to get the capital back, but they failed.

Colonial Wars and Resistance

Acadians and the Wabanaki Confederacy had a long history of resisting British control in Acadia. This happened during the four French and Indian Wars and two local wars (Father Rale's War and Father Le Loutre's War). The Mi'kmaq and Acadians were allies because of their shared Catholic faith and many inter-marriages. The Mi'kmaq had strong military power in Acadia even after the British took over in 1710. They often resisted British rule, and Acadians frequently joined them.

While many Acadians traded with the British, their involvement in the wars showed that many did not want to be ruled by the British. During the first colonial war, King William's War (1688–97), the French privateer Pierre Maisonnat dit Baptiste had many Acadian crew members. Acadians also resisted during the Raid on Chignecto (1696). In Queen Anne's War, Mi’kmaq and Acadians fought back during raids on Grand Pré, Piziquid, and Chignecto in 1704. Acadians also helped the French protect the capital in the Siege of Port Royal (1707) and the final Conquest of Acadia. Acadians and Mi’kmaq also won the Battle of Bloody Creek (1711).

During Father Rale's War, the Maliseet people attacked many ships on the Bay of Fundy. The Mi'kmaq raided Canso, Nova Scotia in 1723, with help from Acadians. In King George's War, a French priest named Abbe Jean-Louis Le Loutre led many efforts involving both Acadians and Mi’kmaq to recapture the capital, like the Siege of Annapolis Royal (1744). During this siege, a French officer took British prisoners to Cobequid. There, an Acadian said the French should have "left their [the English] carcasses behind and brought their skins." Le Loutre was also joined by a famous Acadian resistance leader, Joseph Broussard (Beausoleil). Broussard and other Acadians helped French soldiers in the Battle of Grand Pré.

During Father Le Loutre’s War, the fighting continued. The Mi'kmaq attacked New England Rangers in the Siege of Grand Pré and Battle at St. Croix. When Dartmouth, Nova Scotia was founded, Broussard and the Mi'kmaq raided the village many times to try to stop Protestants from moving into Nova Scotia. Similarly, during the French and Indian War, Mi’kmaq, Acadians, and Maliseet also raided Lunenburg, Nova Scotia, to stop migration there. Le Loutre and Broussard also worked together to resist the British at Chignecto (1750) and later fought with Acadians in the Battle of Beausejour (1755). By 1751, about 250 Acadians had already joined the local militia at Fort Beausejour.

When Charles Lawrence became governor, he took a tougher approach. He was both a government official and a military leader. Lawrence decided on a military solution for the British control of Acadia, which had been unsettled for 45 years. The French and Indian War (also known as the Seven Years' War in Europe) began in 1754. Lawrence's main goals in Acadia were to defeat the French forts at Beausejour and Louisbourg. The British saw many Acadians as a military threat because of their loyalty to the French and Mi'kmaq. The British also wanted to cut off the Acadians' supply lines to Fortress Louisbourg, which supplied the Mi'kmaq.

The French and Indian War and the Expulsion

The British took over Acadia in 1710. For the next 45 years, Acadians refused to sign an oath of loyalty to Britain without conditions. During this time, Acadians took part in military actions against the British. They also kept important supply lines open to the French Fortress of Louisbourg and Fort Beausejour. During the French and Indian War, the British decided to remove any military threat from Acadians and cut off their supply lines to Louisbourg by deporting them from Acadia.

Many Acadians might have signed an unconditional oath if conditions were better, but others were strongly against the British. For those who might have signed, there were several reasons they didn't. One reason was religious, as the British monarch was the head of the Protestant Church of England. Another big concern was that an oath might force Acadian men to fight against France during wartime. They also worried that signing might make their Mi'kmaq neighbors think they were supporting the British claim to Acadia over the Mi'kmaq's. This could put Acadian villages in danger of Mi'kmaq attacks.

In the Grand Dérangement (the Great Upheaval), more than 12,000 Acadians were forced to leave their homes between 1755 and 1764. This was about three-fourths of the Acadian population in Nova Scotia. The British destroyed about 6,000 Acadian homes. Acadians were sent to different Thirteen Colonies from Massachusetts to Georgia. The most deaths happened when the ship Duke William sank. Although there was no plan to separate families, it often happened because of the chaos.

Acadian and Mi’kmaq Resistance

When the Expulsion of the Acadians began during the French and Indian War, the Mi’kmaq and Acadian resistance grew stronger. Much of this resistance was led by Charles Deschamps de Boishébert et de Raffetot. Acadians and Mi’kmaq won battles at Battle of Petitcodiac (1755) and Battle of Bloody Creek (1757). Acadians being deported from Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia, on the ship Pembroke defeated the British crew and sailed to shore. There was also resistance during the St. John River Campaign. Boishebert also ordered the Raid on Lunenburg (1756). In 1756, a group gathering wood near Fort Monckton was attacked, and nine soldiers were killed.

In April 1757, a group of Acadians and Mi'kmaq raided a warehouse near Fort Edward. They killed thirteen British soldiers, took supplies, and burned the building. A few days later, the same group also raided Fort Cumberland.

Some Acadians escaped into the woods and lived with the Mi'kmaq. Some groups fought the British, including one led by Joseph Broussard, known as "Beausoleil," along the Petitcodiac River in New Brunswick. Others went north along the coast, facing hunger and disease. Some were captured and deported or imprisoned at Fort Beausejour (renamed Fort Cumberland) until 1763.

Some Acadians became servants in the British colonies. Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Connecticut passed laws placing Acadians under the care of local officials. The Province of Virginia first agreed to take about a thousand Acadians but later sent most of them to England.

In 1758, after Louisbourg fell, over 3,000 Acadians were sent to northern France. They tried to resettle in places like Châtellerault, Nantes, and Belle Île. The French islands of St. Pierre and Miquelon near Newfoundland became a safe place for many Acadian families. However, they were deported again by the British in 1778 and 1793.

Returning to Nova Scotia

After the Seven Years' War ended in 1763, Acadians were allowed to return to Nova Scotia. But they could not settle in large groups in one area. They were not allowed to go back to Port Royal or Grand-Pré. Some Acadians settled along the Nova Scotia coast and are still there today. Many Acadians who were scattered looked for new homes. Starting in 1764, groups of Acadians began to arrive in Louisiana, which was then controlled by Spain. They eventually became known as Cajuns.

In the 1770s, Nova Scotia Governor Michael Francklin encouraged many Acadians to return. He promised them Catholic worship, land grants, and that there would be no second expulsion. At this time, Nova Scotia included what is now New Brunswick. However, the fertile Acadian farmlands had been settled by New England Planters. Later, Loyalists also took over former Acadian lands. Returning Acadians and those who had escaped expulsion had to settle in other parts of Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. These were often isolated and less fertile lands. The new Acadian settlements had to focus more on fishing and later on forestry.

Important steps in the Acadian return and resettlement included:

- 1767: St. Pierre et Miquelon

- 1772: Census taken

- 1774: Founding of Saint-Anne's church; the Acadian school at Rustico; and the abbey Jean-Louis Beaubien; the Trappistines in Tracadie

- 1785: Movement from Fort Sainte-Anne to the upper Saint John River valley (Madawaska)

The Nineteenth Century

Important events for Acadians in the 1800s:

- Jean-Mandé Sigogne (1763–1844) was a French Catholic priest. He moved to Canada after the French Revolution and became known for his work with Acadians in Nova Scotia.

- 1836: Simon d'Entremont and Frédéric Robichaud became Members of the Legislative Assembly (MLAs) in Nova Scotia.

- 1846: Amand Landry became an MLA in New Brunswick.

- 1847: Henry Wadsworth Longfellow published his famous poem Evangeline.

- 1854: Stanislaw-Francois Poirier became an MLA in Prince Edward Island.

- 1854: The seminary Saint-Thomas in Memramcook, New Brunswick, became the first higher-level school for Acadians.

- 1859: The first history of Acadia, "La France aux colonies," was published in French. Acadians began to learn more about their own history and identity.

Acadian Renaissance

The Acadian Renaissance was a time of cultural revival:

- 1864: The Farmers' Bank of Rustico was founded. This was the earliest known community bank in Canada, led by Rev. Georges-Antoine Belcourt.

- 1867: The first Acadian newspaper, Le Moniteur Acadien (The Acadian Monitor), was published by Israël Landry.

- 1871: The Common Schools Act of 1871 was passed, which stopped the teaching of religion in classrooms.

- 1875: The death of 19-year-old Louis Mailloux in Caraquet by government forces made Acadian nationalism even stronger.

- 1880: The Society of Saint John the Baptiste invited French-speaking people from all over North America to a meeting in Quebec City.

- July 20–21, 1881: Acadian leaders held the first Acadian National Convention in Memramcook, New Brunswick. Its goal was to look after the general interests of the Acadian people. More than 5,000 Acadians attended. They decided that August 15, the Feast of the Assumption of the Virgin Mary, would be chosen to celebrate Acadian culture as National Acadian Day. Other discussions at the convention were about education, farming, moving away, settling new lands, and newspapers. These same topics would come up at later conventions.

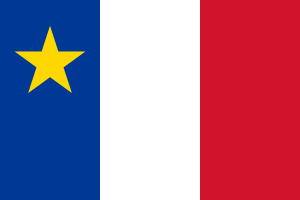

- August 15, 1884: At the second convention in Miscouche, Prince Edward Island, the Acadian flag, an anthem (Ave Maris Stella), and a motto (L'union fait la force - "Unity is strength") were adopted.

- 1885: John A. Macdonald appointed Pascal Poirier from Shediac as the first Acadian senator. A second Acadian newspaper, Le Courrier des Provinces Maritimes, was published.

- 1887: The newspaper L'Evangéline began publishing from Digby. Later, in 1905, it moved to Moncton.

- 1890: The third Acadian convention was held.

The Twentieth Century

More milestones of the Acadian Renaissance:

- 1912: Monsigneur Edouard LeBlanc became the first Acadian bishop in The Maritimes.

- 1917: The Conservative Aubin-Edmond Arsenault became the first Acadian premier of Prince Edward Island.

- 1920: Mgr Alexandre Chiasson became the second Acadian bishop in Chatham and later Bathurst. The Société nationale de l'Assomption started a campaign to build a special church in Grand-Pré, Nova Scotia.

- 1923: Pierre-Jean Véniot became the first Acadian premier of New Brunswick, though he was not elected to the position.

- 1936: The first Acadian credit union (Caisse Populaire Acadien) was founded in Petit-Rocher. The France-Acadie committee was also founded.

- 1955: The first Tintamarre took place. This is a noisy parade where Acadians celebrate their culture.

Equal Opportunity Program

Louis Robichaud, often called "P'tit-Louis" (Little Louis), was the first elected Acadian Premier of New Brunswick. He served from 1960 to 1970. He was first elected to the legislature in 1952 and became the provincial Liberal leader in 1958. He led his party to victory in 1960, 1963, and 1967.

Robichaud updated the province's hospitals and public schools. He also brought in many reforms in an era known as the New Brunswick Equal Opportunity program. This happened at the same time as the Quiet Revolution in Québec. To make these changes, Robichaud changed the way municipal taxes were collected. He expanded the government and worked to make sure that health care, education, and social services were the same quality across the province. He called this "equal opportunity," and it's still an important idea in New Brunswick today.

Some people criticized Robichaud's government, saying it was taking from rich areas to give to poor ones. While it was true that wealthier areas were mostly English-speaking, areas with much poorer services were found all over the province, in both English and French-speaking communities.

Robichaud was key in creating New Brunswick's only French-speaking university, the Université de Moncton, in 1963. This university serves the Acadian population of the Maritime provinces.

His government also passed the New Brunswick Official Languages Act (1969), making the province officially bilingual. When he introduced the law, he said, "Language rights are more than legal rights. They are precious cultural rights, going deep into the revered past and touching the historic traditions of all our people."

In 1977, the Acadian Historic Village officially opened in Caraquet, New Brunswick.

Antonine Maillet

Born in 1929 in Bouctouche, Antonine Maillet is a famous Acadian writer. She writes novels, plays, and is a scholar. Maillet earned her degrees from the Université de Moncton and a Ph.D. in literature from the Université Laval. She won the Governor General's Award for Fiction in 1972 for her book Don l'Orignal. In 1979, Maillet published Pélagie-la-Charrette, which won the prestigious Prix Goncourt. Maillet's character "La Sagouine" (from her book of the same name) inspired "Le Pays de la Sagouine" in her hometown of Bouctouche.

The Twenty-first Century

In 2003, Acadian representatives asked for a special proclamation. Queen Elizabeth II, as the Canadian monarch, officially recognized the deportation. She also set July 28 as a day of commemoration. The Government of Canada observes this day.

Acadian Remembrance Day

The Acadian family associations of New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island decided that December 13 each year should be "Acadian Remembrance Day." This day remembers all Acadians who died because of the deportation. December 13 was chosen to remember the sinking of the Duke William in 1758. Nearly 2,000 Acadians deported from Île-Saint Jean died in the North Atlantic from hunger, disease, and drowning on that ship. This event has been remembered every year since 2004. Participants wear a black star to mark the day.

Acadian World Congress

Starting in 1994, the Acadian community has held an Acadian World Congress in New Brunswick. This congress happens every five years. It was held in Louisiana in 1999, Nova Scotia in 2004, and the Acadian Peninsula of New Brunswick in 2009. The fifth Acadian World Congress in 2014 was hosted by 40 different communities. These communities were in three different provinces and states in two countries: northwestern New Brunswick and Témiscouata, Quebec, in Canada, and Northern Maine in the United States.

Images for kids

-

An Acadian home along Cabot Trail, Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia, 1938.

See also

- Military history of the Acadians

- Military history of Nova Scotia

- Acadians

- Cajun

- Occitans

- Fort Beauséjour and Fortress of Louisbourg

- Henri Peyroux de la Coudreniere

- List of governors of Acadia

- List of conflicts in Canada

- Military history of Canada

- Southern France

- New Brunswick

- Nova Scotia

- Prince Edward Island

- List of years in Canada

- History of Nova Scotia

| Jackie Robinson |

| Jack Johnson |

| Althea Gibson |

| Arthur Ashe |

| Muhammad Ali |