History of Nova Scotia facts for kids

The history of Nova Scotia is a long story, stretching back thousands of years to today. Before Europeans arrived, the land we now call Nova Scotia was home to the Mi'kmaq people. They called their territory Mi'kma'ki. For about 150 years, France claimed this region. A colony grew here, mostly made up of Catholic Acadians and Mi'kmaq. During this time, there were six wars where the Mi'kmaq, French, and some Acadians fought against the British. These included the French and Indian Wars, Father Rale's War, and Father Le Loutre's War. In 1749, during Father Le Loutre's War, the capital moved from Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia to the new town of Halifax, Nova Scotia. The fighting finally ended with a peace ceremony called the Burying the Hatchet ceremony in 1761.

After these wars, many new settlers came to Nova Scotia. These included New England Planters and Foreign Protestants. After the American Revolution, people called Loyalists also moved to the colony. In the 1800s, Nova Scotia became self-governing in 1848. Then, in 1867, it joined the Canadian Confederation, becoming part of Canada.

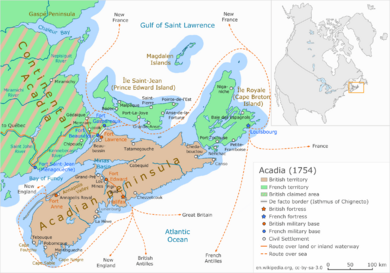

Historically, Nova Scotia was much larger. It included what are now the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island, and even parts of northern Maine. In 1763, Cape Breton Island and St. John's Island (now Prince Edward Island) became part of Nova Scotia. But in 1769, St. John's Island became its own separate colony. Nova Scotia also included present-day New Brunswick until it became a separate province in 1784.

Contents

Early History of Nova Scotia

About 13,500 years ago, the giant glaciers started to melt away from the Maritimes. By 11,000 years ago, the region was mostly free of ice. The first signs of people living here, called Paleo-Indians, appeared soon after the ice left. Evidence from the Debert Palaeo-Indian Site shows people were here 10,600 years ago. They likely followed large animals like caribou onto the newly uncovered land. Over thousands of years, these early people developed the culture, traditions, and language we now know as the Mi’kmaq.

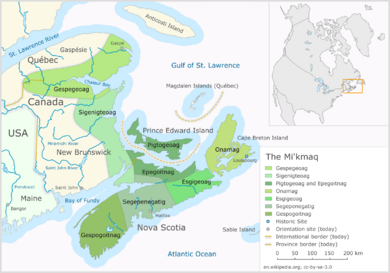

The Mi'kmaq People

For thousands of years, the land of Nova Scotia has been part of Mi'kma'ki, the territory of the Mi'kmaq. Mi'kma'ki included the Maritimes, parts of Maine, Newfoundland, and the Gaspé Peninsula. The Mi'kmaq moved with the seasons. They lived in small camps in the interior during winter and gathered in larger communities along the coast in summer. The climate was not good for farming. So, small groups of families survived by fishing and hunting.

The Mi'kmaq were led by the Santé Mawiómi (Grand Council). This council was headed by the Kji-saqmaw (Grand Council leader). It also included seven Nikanus (District Chiefs), a Kji-Keptin (Grand Captain or war chief), and a Putús (recorder/secretary). Mi'kma'ki was split into seven independent districts. Each district had a Nikanus and a council of Sagamaw (local band chiefs), Elders, and other community leaders. These district councils made laws, ensured fairness, divided fishing and hunting areas, and decided on war or peace. Local groups were led by a Sagamaw and a council of Elders. They were made up of several extended families.

The Mi'kmaq were living in the region when the first European colonists arrived. Europeans first came to North America to take resources from Mi'kmaq land. Early European fishermen would salt their fish at sea and sail home. But by 1520, they started setting up camps on shore to dry their cod. By 1578, about 350 European ships were working around the Saint Lawrence River. Most were fishermen, but more and more were looking for furs to trade.

On June 24, 1610, Grand Chief Membertou became a Catholic and was baptized. The Grand Council and the Pope signed a treaty. This agreement protected French settlers and priests. It also confirmed the Mi'kmaq's right to choose between Catholicism and their own traditions. By signing this treaty, the Catholic church recognized the Mi’kmaq as a sovereign Catholic nation.

European Explorers Arrive

John Cabot, an Italian explorer, was the first European to explore the mainland of North America. His journey changed global social and economic interactions forever. Cabot's trip was funded by Italian banks in London. He set sail in 1496 with permission from King Henry VII of England. When he landed on June 24, 1497, Cabot raised the flags of Venice and the Pope. He claimed the land for the King of England and recognized the Catholic Church's authority. After landing, Cabot spent weeks exploring the coast. Many believe his expedition was the first by Europeans to mainland North America since the Vikings, 500 years before.

Historian Alwyn Ruddock suggested that friars who came with Cabot in 1498 stayed in Newfoundland. They might have started the first Christian settlement on the continent. Nova Scotia was further explored by the Portuguese explorer João Álvares Fagundes in 1520. He was searching south of his fishing settlements in Newfoundland.

17th Century Nova Scotia

French Colonization and Acadia

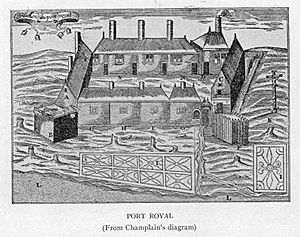

In 1605, French colonists created the first lasting European settlement in what would become Canada. This was at Port Royal, and it became known as Acadia. The French, led by Pierre Dugua, Sieur de Monts, made Port Royal the first capital of their Acadia colony. Acadia (French: Acadie) was a large region in northeastern North America. It included what are now the Canadian Maritime Provinces (New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island), Gaspé in Quebec, and land stretching to the Kennebec River in southern Maine.

By 1621, France had given Port Royal and Acadia back to the British. In that year, King James I of England gave Sir William Alexander a special paper to create the colony of Nova Scotia (“New Scotland”). This new colony included three Canadian provinces and parts of Maine. The capital, Charles Fort, was near today's Annapolis Royal. This Scottish colony only lasted until 1623, when the settlement was abandoned, leaving the area to the French. However, Sir William's efforts are still remembered in Nova Scotia's name, flag, and coat of arms.

Over time, the focus shifted from trading (mostly by male explorers) to settling with families. Ships carrying women and children started arriving in 1632. The Acadian settlements survived because they worked well with the Indigenous peoples of the region. In 1654, English forces from Boston captured Acadia. The Treaty of Breda, signed in 1667, gave Acadia back to France. In 1674, the Dutch briefly took over Acadia, renaming it New Holland. In the late 1600s, Acadians moved from the capital, Port Royal. They started other major Acadian settlements like Grand Pré, Chignecto, Cobequid, and Pisiguit.

During the Acadian period, the British tried six times to conquer the colony by attacking its capital. The French were finally defeated in the Siege of Port Royal (1710). Over the next 50 years, the French and their allies made six unsuccessful attempts to get the capital back.

Acadian Civil War

Acadia experienced what some historians call a civil war from 1640 to 1645. This war was between two governors of Acadia: Charles de Menou d'Aulnay de Charnisay, based at Port Royal, and Charles de Saint-Étienne de la Tour, based in present-day Saint John, New Brunswick.

There were four main battles in this war. La Tour attacked d'Aulnay at Port Royal in 1640. In response, d'Aulnay sailed from Port Royal and blocked La Tour's fort at Saint John for five months. La Tour eventually broke this blockade in 1643. La Tour attacked d'Aulnay again at Port Royal in 1643. D'Aulnay and Port Royal ultimately won the war with the 1645 siege of Saint John. After d'Aulnay died in 1650, La Tour returned to power in Acadia.

Scottish Colony (1629–1632)

From 1629 to 1632, Nova Scotia was briefly a Scottish colony. William Alexander, son of the Earl of Stirling, settled at Charlesfort. This place would later be renamed Port Royal by the French. Lord Ochiltree claimed Île Royale (present-day Cape Breton Island) and settled at Baleine, Nova Scotia. There were three battles between the Scottish and the French: the Raid on St. John (1632), the Siege of Baleine (1629), and the Siege of Cap de Sable (present-day Port La Tour, Nova Scotia) (1630). Nova Scotia was given back to France through a treaty. The French then made Fort Ste. Marie de Grace the capital on the LaHave River before moving it back to Port Royal.

The French quickly defeated the Scottish at Baleine. They established settlements on Île Royale at present-day Englishtown (1629) and St. Peter's (1630). These were the only European settlements on the island until they were abandoned in 1659. Île Royale remained without European settlers for over 50 years until communities were re-established when Louisbourg was founded in 1713.

English Colony (1654–1670)

In 1654, an English expedition led by Robert Sedgwick and John Leverett attacked Acadia. Sedgwick captured the main Acadian ports of Port Royal and Fort Pentagouet. He then gave military command to Leverett. During this time, Leverett and Sedgwick controlled trade in French Acadia for their own benefit. Some in the colony saw Leverett as someone who took advantage of others. Leverett paid for much of the occupation himself and later asked the English government for his money back. They approved the payment, but it depended on an audit of Leverett's finances, which never happened. So, Leverett was still asking for compensation after the monarchy was restored in 1660.

In 1656, Oliver Cromwell gave Acadia/Nova Scotia to Sir Thomas Temple and William Crowne. Soon after, they bought Charles de Saint-Étienne de la Tour’s patent as baronet of Nova Scotia. By doing this, Crowne and Temple agreed to pay La Tour’s debt of £3,379 to a widow in Boston. Temple also took on the cost of the English who had captured the fort on the Saint John River. Crowne provided the money and security for these purchases.

The next year, Crowne, his son John, Temple, and a group of settlers came to Nova Scotia on the ship Satisfaction. Crowne and Temple divided the province between them in February 1658. Crowne took the western part, including the fort of Pentagouet (now Castine, Maine). He also built a trading post on the Penobscot River. The agreement was signed on February 15, 1658. On November 1, 1658, Crowne leased his territory to Captain George Curwin and Ensign Joshua Scottow. Then in 1659, he leased it to Temple for four years at £110 per year. Temple did not pay after the first year but kept the territory. During this time, Crowne lived in Boston, Massachusetts.

Temple had his main base at Penobscot (present-day Castine, Maine). He kept soldiers at Port Royal and Saint John. In 1659, the La Tour fort at the mouth of the Saint John River was abandoned. A new fort was built at Jemseg, about 80 km up the river. Temple set up a trading post there. This location was better because it was safer from sea pirates. Jemseg was also a better place to trade with the Maliseet Indians who came down the river.

When the monarchy was restored in 1660, Crowne went back to England. He wanted to take part in Charles II's coronation and defend his claim to Nova Scotia. Cromwell had given the land to Crowne and Temple. Now that Charles was king, others also claimed the land. These included Thomas Elliot, Sir Lewis Kirke, and heirs of Sir William Alexander. In 1661, the French Ambassador claimed the territory for France. On June 22, 1661, Crowne explained how he and Temple became owners. While in England, Crowne also spoke for the colonists to the council on December 4, 1661. Temple returned to England in 1662. He successfully got a new grant and was made governor. He promised to give Crowne's territory back and pay him, but he did not. Crowne tried to get justice in New England courts, but they said they did not have the power to decide. The colony was eventually given back to France in the 1667 Treaty of Breda. However, the English did not actually give up control until 1670.

18th Century Nova Scotia

Colonial Wars

Nova Scotia experienced six colonial wars over 75 years. These were part of the French and Indian Wars, Father Rale's War, and Father Le Loutre's War. These wars were fought between New England and New France and their Indigenous allies. The British finally defeated the French in North America in 1763. During these wars, Acadians, Mi'kmaq, and Maliseet fought to protect Acadia's border. New France believed this border was the Kennebec River in southern Maine. The wars also involved trying to stop New Englanders from taking the capital of Acadia, Port Royal (see Queen Anne's War). They also tried to prevent New Englanders from settling at Canso (see Father Rale's War) and establishing Halifax (see Father Le Loutre's War).

The 75 years of war ended with the Halifax Treaties between the British and the Mi'kmaq in 1761.

Expulsion of the Acadians

The Expulsion of the Acadians happened between 1755 and 1764. This was during the French and Indian War (which was part of the larger Seven Years' War). It was a British military action against New France. The British first sent Acadians to the Thirteen Colonies. After 1758, they sent more Acadians to Britain and France. In total, out of 14,100 Acadians in the region, about 11,500 were forced to leave their homes.

After Britain won the French and Indian War, about 8,000 New England Planters came to Nova Scotia. They responded to Governor Charles Lawrence's call for settlers from the New England colonies between 1759 and 1768.

Government Changes

Nova Scotia's government structure changed during this time. The colony got a supreme court in 1754 with the appointment of Jonathan Belcher. It also got a Legislative Assembly in 1758. In 1763, Cape Breton Island became part of Nova Scotia. In 1769, St. John's Island (now Prince Edward Island) became a separate colony. The county of Sunbury was created in 1765. It included all of present-day New Brunswick and eastern Maine up to the Penobscot River. In 1784, the western part of the colony was separated and became the province of New Brunswick. Maine became part of the new American state of Massachusetts, but the border was unclear. Cape Breton became a separate colony in 1784. It was returned to Nova Scotia in 1820.

Facing many American sympathizers during the American Revolution, Nova Scotian politicians chose a path of moderation in 1774–75. The royal governor, Francis Legge (1772-1776), fought with the elected assembly over trade and taxes. John Day, elected in 1774, suggested reforms to balance political power. He wanted taxes based on actual wealth and term limits for officials to prevent favoritism. He also thought members of the Executive Council should own significant property. These ideas showed that Nova Scotian politicians understood American demands and hoped to reduce tensions with the British government.

Scottish Settlers

In 1762, the first of the Fuadaich nan Gàidheal (Scottish Highland Clearances) forced many Gaelic families from their traditional lands. The first ship with Hebridean colonists arrived on "St. John's Island" (Prince Edward Island) in 1770. More ships followed in 1772 and 1774. In 1773, a ship called The Hector landed in Pictou, Nova Scotia. It carried 169 settlers, mostly from the Isle of Skye. In 1784, the last rule stopping Scottish settlement on Cape Breton Island was removed. Soon, both PEI and Nova Scotia had many Gaelic speakers. It is estimated that over 50,000 Gaelic settlers moved to Nova Scotia and Cape Breton Island between 1815 and 1870.

Scottish Clans

In the Scottish Highlands, the traditional clan system ended after the failed Rising of 1745. However, Scottish settlers in Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, rebuilt clan settlements that lasted into the early 1900s. The clan system was like a tribe, where a large family group owned land together. Property was usually owned by the whole family. In Scotland, clan members did not accept feudal claims of landlordship. Pioneers in Cape Breton sought out their own relatives and settled near them. Farms passed down through generations within the same clan. Clan members helped each other with tasks like barn raising and shared tools. In Nova Scotia, this system was kept alive through arranged marriages, mutual help, and shared land. This system helped them survive and work efficiently in a tough pioneering environment.

American Revolution's Impact

The American Revolution (1776–1783) greatly shaped Nova Scotia. At first, Nova Scotians were unsure whether to join the rebelling Thirteen Colonies against Britain. Some Nova Scotians went south to fight with the Continental Army against the British. After the war, the United States Congress gave land in Ohio to these supporters.

Rebellions broke out at the Battle of Fort Cumberland (November 1776), the Siege of Saint John (1777), the Maugerville Rebellion in 1776, and the Battle at Miramichi in 1779. However, the Nova Scotia government in Halifax was controlled by wealthy British merchants. For them, loyalty to Britain was more profitable than rebellion. Settlers outside Halifax faced attacks that forced them to choose sides. Many experienced a religious revival that helped them deal with their worries.

Throughout the war, American privateers badly damaged Nova Scotia's economy. They raided many coastal communities. American privateers captured 225 ships coming to or leaving Nova Scotia ports. They also regularly attacked places like Lunenburg, Annapolis Royal, Canso, and Liverpool. American privateers repeatedly raided Canso in 1775 and 1779. They destroyed the fisheries, which were very valuable to Britain. These American raids made many neutral Nova Scotians support the British. By the end of the war, several Nova Scotian privateers were ready to attack American ships.

To protect against American privateer attacks, the 84th Regiment of Foot (Royal Highland Emigrants) was stationed at forts around Atlantic Canada. This strengthened the small local militia. Fort Edward (Nova Scotia) in Windsor, Nova Scotia, was the Regiment's main base. This was to prevent a possible American land attack on Halifax from the Bay of Fundy. There was an American land attack on Nova Scotia, the Battle of Fort Cumberland, followed by the Siege of Saint John (1777).

The British navy in Halifax successfully stopped any American invasion. It also blocked American support for Nova Scotia rebels. It even launched some attacks on New England, like the Battle of Machias (1777). However, the Royal Navy could not fully control the seas. Many American privateers were captured, but many more continued attacking ships and settlements until the war's final months. The Royal Navy struggled to keep British supply lines open. They defended convoys from American and, after 1781, from French attacks. One fierce battle was a naval engagement with a French fleet near Sydney, Nova Scotia.

As more New England Planters (from 1759) and United Empire Loyalists arrived in Mi'kmaki, the Mi'kmaq faced economic, environmental, and cultural challenges. Their treaty rights were being ignored. The Mi'kmaq tried to enforce the treaties by threatening force. At the start of the American Revolution, many Mi'kmaq and Maliseet tribes supported the Americans against the British. They took part in the Maugerville Rebellion and the Battle of Fort Cumberland in 1776. (Mi'kmaq delegates signed the first international treaty, the Treaty of Watertown, with the United States in July 1776. These delegates did not officially represent the Mi'kmaq government, but many individual Mi'kmaq did join the Continental Army.)

During the St. John River expedition in June 1777, Colonel Allan worked hard to get the Maliseet and Mi'kmaq to support the Revolution. He had some success. Many Maliseet left the St John River to join American forces at Machias, Maine. On July 13, 1777, a group of 400 to 500 people, including men, women, and children, left in 128 canoes from the Old Fort Meduetic for Machias. This group arrived at a very good time for the Americans. They helped greatly in defending the post during the attack by Sir George Collier from August 13 to 15. The British did little damage, and the Indigenous people's help earned them thanks from the council of Massachusetts. In June 1779, Mi’kmaq in the Miramichi attacked some British people in the area. The next month, British Captain Augustus Harvey, commanding HMS Viper, arrived. He battled the Mi’kmaq. One Mi’kmaq was killed, and 16 were taken prisoner to Quebec. The prisoners were eventually brought to Halifax. They were released after signing an Oath of Allegiance to the British Crown on July 28, 1779.

Loyalist Migration

After the British lost the Thirteen Colonies, some former Nova Scotian land in Maine became part of the new American state of Massachusetts. British troops from Nova Scotia helped move about 30,000 United Empire Loyalists (Americans who supported Britain). These Loyalists settled in Nova Scotia. They received land grants from the Crown as payment for their losses. Of these, 14,000 went to present-day New Brunswick. Because of this, the mainland part of the Nova Scotia colony was separated. It became the province of New Brunswick with Sir Thomas Carleton as its first governor on August 16, 1784. Loyalist settlements also led to Cape Breton Island becoming a separate colony in 1784. However, it was returned to Nova Scotia in 1820.

The arrival of Loyalists created new communities across Nova Scotia. This included Shelburne, which was briefly one of the largest British settlements in North America. The Loyalists brought new money and skills to the province. Their arrival also caused political tensions between Loyalist leaders and the existing New England Planters. Some Loyalist leaders felt that Nova Scotia's elected leaders were too sympathetic to the American Revolution. Colonel Thomas Dundas wrote in 1786 that Loyalists had "experienced every possible injury from the old inhabitants of Nova Scotia." He believed these older settlers were "even more disaffected towards the British Government than any of the new States ever were." This made him doubt if Nova Scotia would remain loyal for long.

The Loyalist influx also created pressure for settlement land. This pushed Nova Scotia's Mi'kmaq People to the edges, as Loyalist land grants took over unclear native lands. About 3,000 of the Loyalists were Black Loyalists. They founded the largest free Black settlement in North America at Birchtown, near Shelburne. However, unfair treatment and harsh conditions caused about one-third of the Black Loyalists to move to Sierra Leone. In 1792, Black Loyalists from Nova Scotia founded Freetown. They became known in Africa as the Nova Scotian Settlers.

Many Gaelic-speaking Highland Scots moved to Cape Breton and the western mainland in the late 1700s and 1800s. In 1812, Sir Hector Maclean (the 7th Baronet of Morvern and 23rd Chief of the Clan Maclean) moved to Pictou. He brought almost his entire community of 500 people from Scotland.

Decline of Slavery (1787–1812)

While many Black people who came to Nova Scotia during the American Revolution were free, others were not. Black slaves also arrived in Nova Scotia as property of White American Loyalists. In 1772, before the American Revolution, the Somerset v Stewart decision freed James Somerset, a slave. This was followed by Knight v. Wedderburn in Scotland in 1778. These decisions influenced Nova Scotia. In 1788, James Drummond MacGregor from Pictou published the first anti-slavery writings in Canada. He started buying slaves' freedom and criticized Presbyterian church members who owned slaves. In 1790, John Burbidge freed his slaves.

Led by Richard John Uniacke, the Nova Scotian legislature refused to make slavery legal in 1787, 1789, and again on January 11, 1808. Two chief justices, Thomas Andrew Lumisden Strange (1790–1796) and Sampson Salter Blowers (1797–1832), fought a "judicial war" to free slaves in Nova Scotia. They were highly respected in the colony. By the end of the War of 1812 and the arrival of the Black Refugees, few slaves remained in Nova Scotia. The Slave Trade Act outlawed the slave trade in the British Empire in 1807. The Slavery Abolition Act of 1833 outlawed slavery completely.

19th Century Nova Scotia

Early 19th Century

Renewed Wars with France

The French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars first caused problems for Nova Scotia. Fishing was disrupted, and trade with the West Indies suffered from French attacks. However, military spending in the colony gradually led to more wealth. Many Nova Scotian merchants equipped their own privateer ships. These ships attacked French and Spanish vessels in the West Indies. The growing colony built new roads and lighthouses. In 1801, a lifesaving station was set up on Sable Island to help with the many shipwrecks there.

War of 1812

During the War of 1812 with the United States, Nova Scotia became a major military base for the British. It was the center for the British Royal Navy's blockade and naval raids on the United States. The colony also helped the war effort by buying or building privateer ships. These ships captured 250 American vessels. The town of Liverpool, Nova Scotia, led the colony's privateers. The schooner Liverpool Packet captured over 50 ships in the war, more than any other privateer in Canada. The Sir John Sherbrooke (Halifax), owned by Liverpool and Halifax, was also very successful. Other communities joined the privateer campaign. These included Annapolis Royal, Windsor, and Lunenburg, Nova Scotia. Three people from Lunenburg bought a privateer schooner and named it Lunenburg on August 8, 1814. This ship captured seven American vessels.

Perhaps the most dramatic moment for Nova Scotia in the war was when HMS Shannon brought the captured American frigate USS Chesapeake into Halifax Harbour in 1813. The captain of the Shannon was injured, and Nova Scotian Provo Wallis took command to escort the Chesapeake to Halifax. Many prisoners were held at Deadman's Island, Halifax. At the same time, HMS Hogue captured the American privateer Young Teazer off Chester, Nova Scotia.

On September 3, 1814, a British fleet from Halifax, Nova Scotia, began to attack Maine. They wanted to reclaim British land east of the Penobscot River, which they called "New Ireland." Taking "New Ireland" from New England had been a goal for the British and Nova Scotian settlers since the American Revolution. The British expedition included eight warships and ten transport ships carrying 3,500 British soldiers. They were led by Sir John Coape Sherbrooke, then Lieutenant Governor of Nova Scotia. On July 3, 1814, the expedition captured Castine, Maine. They then raided Belfast, Machias, Eastport, Hampden, and Bangor (see Battle of Hampden). After the war, Maine was returned to America through the Treaty of Ghent. The British returned to Halifax. With the war spoils they took from Maine, they built Dalhousie University (established 1818).

The Black Refugees from the War of 1812 were African American slaves who fought for the British. They were then moved to Nova Scotia. These Black Refugees were the second group of African Americans, after the Black Loyalists, to join the British and be relocated to Nova Scotia. However, some people also left the colony because of the difficulties they faced. Reverend Norman McLeod led about 800 Scottish residents from St. Anns, Nova Scotia, to Waipu, New Zealand, in the 1850s.

Labour Conditions

From 1775 to 1820, officials at the Halifax Naval Yard took bribes from workers. They also practiced widespread nepotism, giving jobs to family members. Laborers faced poor working conditions and limited freedoms. However, they stayed for many years because wages were high and more stable than other jobs. Unlike almost any other work, the yards paid disability benefits for injured men and retirement pensions for those who worked there their whole careers.

Nova Scotia had one of the first labor organizations in what became Canada. By 1799, workers set up a Carpenters' Society in Halifax. Soon, other skilled workers tried to organize. Businessmen complained. In 1816, Nova Scotia passed a law against trade unions. This law stated that many master tradesmen, journeymen, and workmen in Halifax and other parts of the province had tried to control wages through illegal meetings. Unions remained illegal until 1851.

Responsible Government

Nova Scotia was the first colony in British North America and the British Empire to achieve responsible government. This happened in January–February 1848, making it self-governing. This was thanks to the efforts of Joseph Howe. In 1758, Nova Scotia also became the first British colony to establish representative government. This was remembered in 1908 by building the Dingle Tower.

Latter 19th Century

The first school for the deaf in Atlantic Canada, the Halifax School for the Deaf, opened on Göttingen St., Halifax, in 1856. The Halifax School for the Blind opened on Morris Street in 1871. It was the first residential school for the blind in Canada.

Nova Scotians fought in the Crimean War. The Welsford-Parker Monument in Halifax is the oldest war monument in Canada (1860). It is the only Crimean War monument in North America. It remembers the Siege of Sevastopol (1854–1855). Nova Scotians also took part in the Indian Mutiny. Two famous Nova Scotians were William Hall (VC) and Sir John Eardley Inglis. Both were involved in the Siege of Lucknow. The 78th (Highlanders) Regiment of Foot were known for their role in the siege. They were later stationed at Citadel Hill (Fort George).

American Civil War

Over 200 Nova Scotians fought in the American Civil War (1861–1865). Most joined infantry regiments in Maine or Massachusetts. However, one in ten served the Confederacy (the South). The total number was likely around 2,000, as many young men had moved to the U.S. before 1860. Some Nova Scotians chose peace, neutrality, or were against Americans. But there were also strong financial reasons to join the well-paid Northern army. The long tradition of moving out of Nova Scotia, combined with a desire for adventure, attracted many young men.

The British Empire, including Nova Scotia, declared neutrality. Nova Scotia greatly benefited from trade with the Union (the North). Nova Scotia was the site of two small international incidents during the war. These were the Chesapeake Affair and the escape of the CSS Tallahassee from Halifax Harbour. Confederate sympathizers helped the Tallahassee escape. Nova Scotia was a hub for Confederate Secret Service agents and sympathizers. It also played a role in blockade running, bringing weapons mostly from Britain. Blockade runners stopped in Halifax to rest and refuel. They then tried to pass through the Union blockade to deliver supplies to the Confederate Army. Nova Scotia's role in arms trafficking to the South was so clear that the Acadian Recorder in 1864 called Halifax's efforts "mercenary aid to a fratricidal war."

U.S. Secretary of State William H. Seward complained on March 14, 1865:

Halifax has been for more than one year, and yet is, a naval station for vessels which, running the blockade, furnish supplies and munitions of war to our enemy, and it has been made a rendezvous for those piratical cruisers which come out from Liverpool and Glasgow, to destroy our commerce on the high seas, and even to carry war into the ports of the United States. Halifax is a postal and despatch station in the correspondence between the rebels at Richmond and their emissaries in Europe. Halifax merchants are known to have surreptitiously imported provisions, arms, and ammunition from our seaports, and then transshipped them to the rebels. The governor of Nova Scotia has been neutral, just, and friendly; so were the judges of the province who presided on the trial of the Chesapeake. But then it is understood that, on the other hand, merchant shippers of Halifax, and many of the people of Halifax, are willing agents and abettors of the enemies of the United States, and their hostility has proved not merely offensive but deeply injurious.

The war made many fear that the North might try to take over British North America. This fear grew after the Fenian raids began. Many Americans saw the Fenian raids as revenge for British-Canadian support for Confederate activities against the Union during the Civil War. In response, volunteer regiments were formed across Nova Scotia. British commander and Lieutenant Governor of Nova Scotia Charles Hastings Doyle led 700 troops from Halifax. They went to stop a Fenian attack on the New Brunswick border with Maine. This scare was one of the main reasons Britain allowed the creation of Canada in 1867. They wanted to avoid another conflict with America and leave Nova Scotia's defense to a Canadian government.

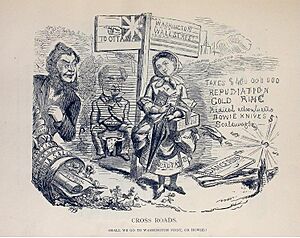

Canadian Confederation

The British North America Act made Nova Scotia part of the Dominion of Canada on July 1, 1867. Premier Charles Tupper worked hard to make this union happen. But it was controversial. Many Nova Scotians felt strong local pride. Protestants feared Catholics, and people generally distrusted Canadians. They also worried about losing free trade with America. Tupper's refusal to ask Nova Scotian voters about the union made these feelings stronger. A movement to leave Canada grew, led by Joseph Howe. Howe's Anti-Confederation Party won almost all the seats in the next election on September 18, 1867. They won 18 of 19 federal seats and 36 of 38 seats in the provincial legislature. In 1868, the Nova Scotia House of Assembly passed a motion refusing to recognize Confederation. This motion has never been cancelled.

With the important Hants County by-election of 1869, Howe successfully shifted the province's goal. Instead of trying to leave Confederation, they simply sought "better terms" within it. Despite its temporary popularity, Howe's movement failed to withdraw from Canada because London was determined the union would continue. Howe did succeed in getting better financial terms for the province. He also gained a national political position for himself.

Long-term negative factors came into play. In 1865, the American Civil War ended, and with it, all the extra business it had created. In 1866, the Canadian–American Reciprocity Treaty ended. This led to higher American taxes on goods from Nova Scotia, which hurt trade. Over time, the change from wooden sailing ships to steel steamships reduced the advantages Nova Scotia had before 1867. For decades, many residents complained that Confederation had slowed the province's economic progress. They felt it lagged behind other parts of Canada. The idea of "Repeal," as anti-confederation became known, reappeared in the 1880s. It then changed into the Maritime Rights Movement in the 1920s. Some Nova Scotia flags flew at half-mast on Dominion Day (Canada Day) even at that time.

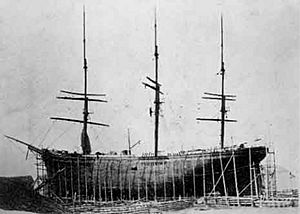

Golden Age of Sail

In the second half of the 19th century, Nova Scotia became a world leader in building and owning wooden sailing ships. Nova Scotia produced internationally famous shipbuilders like Donald McKay, John M. Blaikie, and William Dawson Lawrence. It also had ship designers like Ebenezer Moseley and the propeller inventor John Patch. Famous ships included the barque Stag, known for its speed, and the ship William D. Lawrence. This was the largest wooden ship ever built in Canada. Sailors like Captain George "Rudder" Churchill of Yarmouth became famous for their voyages. The province also produced a notable 19th-century female sailor, Bessie Hall from Annapolis Royal. The most famous Nova Scotian sailor was Joshua Slocum. He became the first person to sail alone around the world in 1895. Competition from steamships in the late 19th century ended the Golden Age of Sail. However, this legacy continued to inspire sailors and the public into the next century, especially with the many racing victories of the Bluenose schooner.

The population grew steadily from 277,000 in 1851 to 388,000 in 1871. This was mostly due to natural growth, as there was little immigration. This era is often called the province's golden age. This is because of economic growth, the growth of towns and villages, the maturing of businesses and institutions, and the success of industries like shipbuilding. The idea of a past golden age became popular in the early 1900s. Economic reformers in the Maritime Rights Movement used it. The tourism industry in the 1930s also used it to attract tourists to a romantic era of tall ships and antiques.

Recent historians, using census data, have questioned the idea of Nova Scotia's golden age. From 1851 to 1871, there was an overall increase in wealth per person. However, like typical 19th century capitalism, most of the gains went to wealthy city dwellers. These were especially businessmen and financiers living in Halifax. The wealth held by the top 10 percent rose significantly over two decades. But there was little improvement in wealth in rural areas, where most of the population lived. Similarly, Gwyn reports that gentlemen, merchants, bankers, mine owners, shipowners, shipbuilders, and master mariners thrived. However, most families were headed by farmers, fishermen, craftspeople, and laborers. Many of them, and many widows, lived in poverty. People started leaving the province more and more as the 19th century continued. So, the era was indeed a golden age, but mainly for a small and powerful elite.

North-West Rebellion

The Halifax Provisional Battalion was a military unit from Nova Scotia, Canada. It was sent to fight in the North-West Rebellion in 1885. The battalion was led by Lieutenant-Colonel James J. Bremner. It included 168 non-commissioned officers and men from The Princess Louise Fusiliers, 100 from the 63rd Battalion Rifles, and 84 from the Halifax Garrison Artillery, along with 32 officers. The battalion left Halifax for the North-West on Saturday, April 11, 1885. They stayed for almost three months.

Before Nova Scotia's involvement, the province was still unhappy with Canada. This was because of how the colony was forced into Canada. The celebration that followed the Halifax Provisional Battalion's return by train across the country sparked a new sense of national pride in Nova Scotia. Prime Minister Robert Borden stated that "up to this time Nova Scotia hardly regarded itself as included in the Canadian Confederation... The rebellion evoked a new spirit... The Riel Rebellion did more to unite Nova Scotia with the rest of Canada than any event that had occurred since Confederation." Similarly, in 1907, Governor General Earl Grey declared, "This Battalion... went out Nova Scotians, they returned Canadians." The wrought iron gates at the Halifax Public Gardens were made in the Battalion's honor.

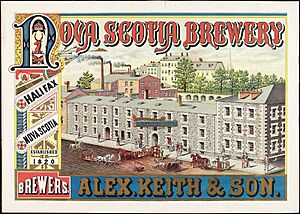

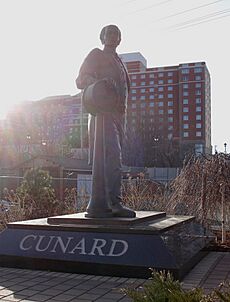

19th Century Economic Growth

Throughout the 19th century, many businesses grew in Nova Scotia. They became important nationally and internationally. These included The Starr Manufacturing Company, Susannah Oland and Sons Co., the Bank of Nova Scotia, Cunard Line, Alexander Keith's Brewery, and Morse's Tea Company.

Most people were farmers, and agriculture was the main part of the economy. The rural situation reached its peak in 1891. This included total rural population, farmland, grain production, cattle production, and the number of farms. Then, it steadily declined into the 21st century. Apples and dairy products were exceptions to this decline in the 20th century.

Nova Scotia's trade and tariff patterns between 1830 and 1866 suggest the colony was already moving towards free trade. This was before the Reciprocity Treaty of 1854 with the U.S. took effect. The treaty brought small additional direct benefits. The Reciprocity Treaty supported the earlier move towards free trade. It also boosted the export of goods sold mainly to the United States, especially coal.

Halifax was the home of Samuel Cunard. With his father, Abraham, a master ship's carpenter, he founded the A. Cunard & Co. cargo shipping company. Later, he founded the Cunard Line, a source of pride for the British Empire. Samuel built on his father's modest waterfront properties. He created a series of businesses that changed transatlantic shipping and passenger travel with the introduction of steam and steel. Cunard was a supporter of the community. He was active in charity and helped found the Chamber of Commerce. There, he found business partners for his ventures in banking, mining, and other businesses. He became one of the largest landowners in the Maritime Provinces.

John Fitzwilliam Stairs (1848–1904), from the powerful Stairs family, expanded the family's many businesses. He merged rope-making companies and sugar refineries. Then, he created the steel industry in the province. To find new money sources in the region, Stairs became a leader in creating legal and regulatory systems for these new financial structures. The family finally sold its businesses in 1971, after 160 years.

After Confederation, supporters of Halifax expected federal help. They wanted to make the city's natural harbor Canada's official winter port. They hoped it would be a gateway for trade with Europe. Halifax had advantages, like its location near the Great Circle route. This made it the closest mainland North American port to Europe. But the new Intercolonial Railway (ICR) took an indirect, southerly route for military and political reasons. The national government did little to promote Halifax as Canada's winter port. Ignoring calls for national pride and the ICR's own efforts to promote traffic to Halifax, most Canadian exporters sent their goods by train through Boston or Portland. No one was interested in paying for the large port facilities Halifax needed. It took the First World War to finally make Halifax's harbor important on the North Atlantic.

Unionization became legal after 1851. It was based on skilled crafts, except in coal mines and steel plants, where unskilled men could also join. There was an increase in industrial unionism as industry expanded. International unions, with a strong American influence, became important. International unions started in 1869 when a local of the International Typographical Union was formed in Halifax. In 1870, woodworking trades started their union. Different unions joined together to support strikes. This was seen in the Amalgamated Trade Unions of Halifax, formed in 1889. It was followed by the Halifax District Trades and Labour Council in 1898. By the end of the 19th century, there were over 70 local unions in the province.

20th Century Nova Scotia

Established in 1894, the Local Council of Women of Halifax (LCWH) became an important group for women's rights in the early 20th century. They worked to improve the lives of women and children. One of their biggest achievements was their 24-year fight for women's right to vote, which they won in 1918.

Early 20th Century Economy

In the early 20th century, the Leah Tibert Steel and Coal Company (known as Scotia) became a huge industrial company. It grew quickly and made good profits from exporting coal, pig iron, and steel products to Canadian and international markets. At first, its convenient location by the sea and control over all production steps helped it grow. It expanded through mergers and buying other companies. However, long-term negative factors included being broken into smaller parts, limited markets in the Maritime region, rising costs, low-quality raw materials, and a lack of outside support. When Scotia (later called DOSCO—Dominion Steel and Coal Corporation) finally closed in the 1960s, it was a big blow to many towns. These towns, like Florence, Reserve Mines, Sydney Mines, Trenton, and New Glasgow, had relied on its well-paying jobs and the political activity of its workers.

However, rural areas steadily lost population, especially the eastern counties. Liberal premiers George Henry Murray (1896–1923) and Ernest H. Armstrong (1923–25) started programs to improve rural life and modernize farming. They got federal help through loans and grants for agriculture, roads, and immigration. Murray was criticized for being too careful with his reforms. Armstrong, even with a Liberal federal government, could not keep the help flowing. The situation worsened with the post-war economic downturn. This brought the United Farmers Party to power in 1920 in the hardest-hit areas of eastern Nova Scotia. The Liberals' failure to stop the area's decline led to their defeat in 1925. The "rejuvenated" Conservatives won by taking advantage of Armstrong's weaknesses.

Labour Unions

The Provincial Workmen's Association started in 1879 as a miners' union. In 1898, facing a challenge from the Knights of Labor, it tried to include unions from all industries in the province. The first local union of the United Mine Workers was formed in 1908. After a struggle for control of the labor movement among miners, the Provincial Workmen's Association was dissolved in 1917. By 1919, the United Mine Workers took control of the coal miners. Their success was due to the strong leadership of J. B. McLachlan (1869–1937). He left the coal mines of Scotland for Canada in 1902. He became a Communist (1922 to 1936) and promoted a strong union and independent labor politics. McLachlan's battles with the American UMWA leadership, especially the strict John L. Lewis, showed his dedication to democratic unionism for the miners. But Lewis won and removed McLachlan from power.

Women played an important, though often unseen, role in supporting the union movement in coal towns during the difficult 1920s and 1930s. They never worked in the mines. But they provided emotional support, especially during strikes when paychecks did not arrive. They managed family finances and encouraged other wives who might have otherwise convinced their husbands to accept company terms. Women's labor leagues organized various social, educational, and fundraising events. Women also bravely confronted "scabs" (strike breakers), policemen, and soldiers. They had to make food last and be creative in clothing their families.

Second Boer War

During the Second Boer War (1899–1902), the First Contingent of Canadian soldiers included seven companies from across Canada. The Nova Scotia Company (H) had 125 men. The entire First Contingent was 1,019 soldiers. Eventually, over 8,600 Canadians served. The troops gathered in Quebec. On October 30, 1899, the ship Sardinian sailed the troops for four weeks to Cape Town.

The Boer War was the first time large groups of Nova Scotian troops served abroad. (Individual Nova Scotians had served in the Crimean War). The Battle of Paardeberg in February 1900 was the second time Canadian soldiers fought in a battle abroad. (The first was the Canadian involvement in the Nile Expedition). Canadians also saw action at the Battle of Faber's Put on May 30, 1900. On November 7, 1900, the Royal Canadian Dragoons fought the Boers in the Battle of Leliefontein. They saved British guns from being captured during a retreat from the Komati River.

About 267 Canadians died in the War. 89 men were killed in action, 135 died of disease, and the rest died from accidents or injuries. 252 were wounded. Of all the Canadians who died, the most famous was young Lieutenant Harold Lothrop Borden of Canning, Nova Scotia. Harold Borden's father was Sir Frederick W. Borden, Canada's Minister of Militia. He strongly supported Canadian involvement in the war. Another famous Nova Scotian who died in the war was Charles Carroll Wood. He was the son of the well-known Confederate naval captain John Taylor Wood and the first Canadian to die in the war.

First World War

During World War I, Halifax became a major international port and naval facility. The harbor became a key shipping point for war supplies. It was also a departure point for troop ships going to Europe from Canada and the United States. Hospital ships bringing back wounded soldiers also used the port. These factors led to a major military, industrial, and residential expansion of the city.

On Thursday, December 6, 1917, the city of Halifax was destroyed by a huge explosion. A French cargo ship, full of wartime explosives, accidentally crashed into a Norwegian ship in "The Narrows" part of the Halifax Harbour. About 2,000 people were killed by debris, fires, or collapsed buildings. Over 9,000 people were injured. This is still the world's largest accidental man-made explosion.

Interwar Period and the Second World War

Gabriel Sylliboy was the first Mi'kmaq elected as Grand Chief in 1919. He was also the first to fight for treaty recognition in the Supreme Court of Nova Scotia in 1929. Specifically, he fought for the Treaty of 1752.

Nova Scotia was hit hard by the worldwide Great Depression that started in 1929. Demand for coal and steel dropped sharply, as did prices for fish and lumber. Prosperity returned during World War II. Halifax again became a major staging point for convoys going to Britain. Liberal premier Angus L. Macdonald was a dominant political figure, serving from 1933–1940 and 1945–1954. Macdonald dealt with the mass unemployment of the 1930s by putting jobless people to work on highway projects. He believed direct government relief payments would weaken moral character and discourage personal effort. However, his government also lacked the money to fully participate in federal relief programs that required matching contributions from the provinces.

The Antigonish Movement offered a "middle way" to help people affected by the depression. It involved cooperative ventures controlled by the people. This Catholic initiative was started by Reverend Moses Coady of St. Francis Xavier University in 1928. He sought an alternative to socialism or capitalism that the Church approved. The cooperatives were organized at the local level. They brought together fishermen, farmers, miners, and factory workers, especially in the eastern districts. They set up local fish processing plants, credit unions, housing co-ops, and cooperative stores. Ownership and control were in the hands of the people directly involved. The movement declined after 1950.

During World War II, thousands of Nova Scotians went overseas. Halifax became a key staging point for the Atlantic convoys. The Navy base at CFB Halifax became the headquarters of Rear Admiral Leonard W. Murray during the Battle of the Atlantic. One Nova Scotian, Mona Louise Parsons, joined the Dutch resistance. She was captured and imprisoned by the Nazis for almost four years.

Latter 20th Century (1945–2000)

Led by minister William Pearly Oliver, the Nova Scotia Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NSAACP) was formed in 1945. It grew out of the Cornwallis Street Baptist Church. The organization aimed to improve the lives of Black Nova Scotians. It also worked to improve relations between Black and white people, cooperating with private and government groups. 500 Black Nova Scotians joined the organization. By 1956, the NSAACP had branches in Halifax, Cobequid Road, Digby, Weymouth Falls, Beechville, Inglewood, Hammonds Plains, and Yarmouth. Preston and Africville branches were added in 1962. That same year, New Road, Cherrybrook, and Preston East also asked for branches. In 1947, the Association successfully took the case of Viola Desmond to the Supreme Court of Canada. It also pushed the Children's Hospital in Halifax to allow Black women to become nurses. It advocated for inclusion and challenged racist lessons in the Department of Education. The Association also developed an Adult Education program with the government.

After the war, Angus L. Macdonald started large spending programs. These were for services like health, education, labor union protection, and pensions.

Conservative Robert L. Stanfield served as premier from 1956–1967. Stanfield was practical and favored some government involvement in the economy. However, he was careful about social policy and did not want to promote a full welfare state. Still, new hospitals were built, paid for by a sales tax. After 1960, there was more focus on provincial help for local towns and cities in health and education. Money was also given for university expansion. Overall, Stanfield, though a conservative, believed the government had a positive role in helping citizens overcome poverty, illness, and unfair treatment. He accepted the need to raise taxes to pay for these services.

On September 2, 1998, Swissair Flight 111 crashed into the Atlantic Ocean in St. Margaret's Bay. All 229 people on board the McDonnell Douglas MD-11 died. There are two memorials for the victims. One is at The Whalesback, northwest of Peggy's Cove. The other is at Bayswater, where the plane's wreckage was recovered.

Provincial Relations with Acadians and Mi'kmaqs in the Late 20th Century

The Acadian Federation of Nova Scotia (French: Fédération acadienne de la Nouvelle-Écosse) was created in 1968. Its goal is to "promote the growth and overall development of the Acadian and Francophone community of Nova Scotia." The Fédération acadienne is the official voice for Acadian and French-speaking people in Nova Scotia. The Federation currently has 29 regional, provincial, and institutional members. In 1996, the Federation was key in establishing the Acadian School Board (Conseil scolaire acadien provincial) in the province.

In 1997, the Mi'kmaq-Nova Scotia-Canada Tripartite Forum was created. The Nova Scotia government and the Mi’kmaq community have developed the Miꞌkmaw Kinaꞌmatnewey. This is a very successful First Nation Education Program in Canada. In 1982, the first Mi’kmaq-operated school opened in Nova Scotia. By 1997, all education for Mi’kmaq on reserves became their own responsibility. There are now 11 band-run schools in Nova Scotia. Nova Scotia now has the highest rate of Indigenous students staying in school in the country. More than half the teachers are Mi’kmaq. From 2011 to 2012, there was a 25 percent increase in Mi’kmaq students going to university. Atlantic Canada has the highest rate of Indigenous students attending university in the country.

21st Century Nova Scotia

On April 14, 2010, the Lieutenant Governor of Nova Scotia, Mayann Francis, used her special power to grant Viola Desmond a posthumous free pardon. This was the first such pardon given in Canada. A free pardon is a very rare action. It is based on innocence and recognizes that a conviction was wrong. The government of Nova Scotia also apologized. This effort was led by Desmond's younger sister, Wanda Robson, and a professor from Cape Breton University, Graham Reynolds. They worked with the Nova Scotia government to clear Desmond's name and admit the government's mistake. In honor of Desmond, the provincial government named the first Nova Scotia Heritage Day after her.

In the same year, on August 31, the governments of Canada and Nova Scotia signed an important agreement with the Mi'kmaq Nation. This agreement created a process where the federal government must talk with the Mi'kmaq Grand Council before doing any activities or projects that affect the Mi'kmaq in Nova Scotia. This covers most, if not all, actions these governments might take in that area. This is the first such cooperative agreement in Canadian history that includes all First Nations within an entire province.

See also

- Acadiensis, scholarly history journal covering Atlantic Canada

- Nova Scotia Federation of Labour

- List of National Historic Sites in Nova Scotia

- History of Acadia

- Black Nova Scotians

- Military history of Nova Scotia

- Military history of the Mi’kmaq People

- Military history of the Maliseet people

- Military history of the Acadians

- History of the Acadians

- History of the Halifax Regional Municipality

- Royal Nova Scotia Historical Society

|

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |