Edward Mitchell Bannister facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Edward Mitchell Bannister

|

|

|---|---|

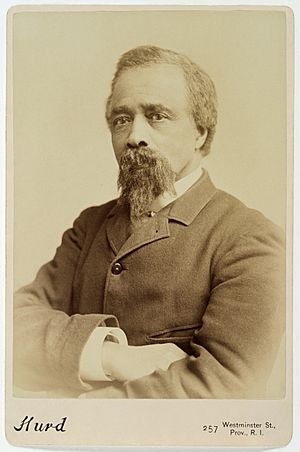

Cabinet card by Gustine L. Hurd, c. 1880

|

|

| Born | November 2, 1828 Saint Andrews, New Brunswick, British North America

|

| Died | January 9, 1901 (aged 72) |

| Resting place | North Burial Ground |

| Nationality | Canadian, American |

| Other names | Edwin, Ned |

| Education | Lowell Institute |

| Style | American Barbizon school |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Awards | First Prize Philadelphia Centennial 1876 Under the Oaks |

Edward Mitchell Bannister (born November 2, 1828 – died January 9, 1901) was a talented oil painter. He was part of the American Barbizon school, a group of artists who painted landscapes in a soft, natural style. Edward was born in Canada but lived most of his adult life in New England in the United States.

Along with his wife, Christiana Carteaux Bannister, he was an important leader in African-American communities. They were active in the Boston movement to end slavery, known as abolitionism. Bannister became famous across the country when he won first prize for a painting at the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition. He also helped start the Providence Art Club and the Rhode Island School of Design.

Bannister's paintings often showed peaceful country scenes, called pastoral subjects. He admired the French artist Jean-François Millet and the French Barbizon School, who painted similar scenes. Edward was also a lifelong sailor, and he found inspiration in the beautiful Rhode Island seaside. He loved to try new things in his art. His paintings show his deep thoughts about nature and his amazing skill with colors and light. He started his career as a photographer and portrait painter before becoming well-known for his landscapes.

Later in his life, Bannister's style of landscape painting became less popular. He and his wife moved to smaller homes as his painting sales went down. After he died in 1901, people didn't talk about his art as much. But in the 1960s and 1970s, places like the National Museum of African Art helped bring his work back into the spotlight.

Contents

Edward Mitchell Bannister: A Pioneering Artist

Early Life and Artistic Dreams

Edward Bannister was born on November 2, 1828, in Saint Andrews, New Brunswick, near the St. Croix River. His father, Edward Bannister, was Black and from Barbados. His mother, Hannah Alexander Bannister, raised Edward and his younger brother William after their father died in 1832.

When he was young, Edward worked as a shoemaker's helper. But even then, his friends and family noticed how good he was at drawing. Bannister said his mother first sparked his interest in art. After she died in 1844, Edward and his brother lived on a farm owned by a wealthy lawyer named Harris Hatch. There, Edward practiced drawing by copying family portraits and pictures from books.

Edward and his brother worked on ships for a few months. Then, in the late 1840s, they moved to Boston. In the 1850 census, they were listed as barbers. Being barbers and having mixed heritage gave them a good standing in Boston's middle class.

Edward wanted to be a painter, but it was hard for him to find a teacher or art school because of racial prejudice. Even though Boston was a strong center for ending slavery, it was still very segregated in 1860. Bannister later shared his frustration about not being able to get proper art training. He felt that his success came more from his natural talent than from lessons.

In 1854, Bannister received his first oil painting job from an African American doctor, John van Salee de Grasse. This painting was called The Ship Outward Bound. Dr. DeGrasse also asked Bannister to paint portraits of him and his wife. Support from the African American community was very important for Bannister's early career. Black communities wanted to show their contributions to art and culture. Painting portraits was a great way for them to express freedom and opportunity. This is why many of Bannister's first paintings were portraits.

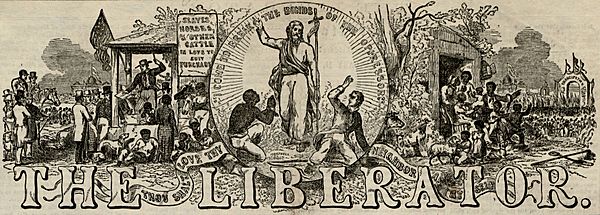

Bannister learned about other African American artists like Robert S. Duncanson through anti-slavery newspapers like The Anglo-African and The Liberator. Their work made his own artistic dreams seem more possible. Even though many art places didn't allow Black people, Bannister could go to some, like the Boston Athenæum library. There, he could see European art and paintings of ships by artists like Robert Salmon.

Fighting for Freedom and Art

In 1853, Bannister met Christiana Carteaux, a successful hairdresser and businesswoman. She was born in Rhode Island to African American and Narragansett parents. They met when Edward applied to work as a barber in her salon. Both were active in Boston's movement to end slavery. Barbershops were important meeting spots for African American abolitionists.

Edward and Christiana married on June 10, 1857. She became his most important supporter. For two years, they lived with Lewis Hayden and Harriet Bell Hayden at 66 Southac Street. This house was a stop on the Underground Railroad, a secret network that helped enslaved people escape to freedom.

By 1858, Bannister was listed as an artist in Boston's city guide. Around 1862, he spent a year learning photography in New York. He likely did this to help support his painting. He then worked as a photographer, making and coloring pictures. One of his first commissioned portraits was of Prudence Nelson Bell in 1864. Around this time, he got a studio space in the Studio Building in Boston. There, he met other famous artists.

Bannister was part of Boston's African American art community. He sang in the Crispus Attucks Choir, which performed anti-slavery songs. He also acted in a club and attended meetings for Black citizens. His name appeared on many public requests published in The Liberator.

Edward and Christiana were strong members of the Twelfth Baptist Church, which was very active in the anti-slavery movement. Bannister helped organize meetings to support escaped enslaved people and to celebrate the Emancipation Proclamation, which declared many enslaved people free.

During the U.S. Civil War, Christiana worked to get equal pay for African American soldiers. She also organized a fair in 1864 to raise money for Black regiments who hadn't been paid. Bannister donated his painting of Robert Gould Shaw, the commander of the 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment who died in battle. This painting helped raise money for the soldiers. The painting was called "Our Martyr" by abolitionists. It was bought by the state of Massachusetts, but its location is now unknown.

Bannister also took part in other forms of activism. In 1865, he led about 200 members of his church's Sunday School in a large celebration on Boston Common. They marched with a banner that said "Equal rights for all men."

Bannister eventually studied at the Lowell Institute with artist William Rimmer. Rimmer taught drawing classes at night, which was good for Bannister because he worked during the day as a photographer. Bannister knew that artistic anatomy was a weak point for him, and Rimmer was known for his skill in that area. Through Rimmer, Bannister was inspired by the Barbizon School-style paintings of William Morris Hunt. At the Lowell Institute, Bannister became lifelong friends with painter John Nelson Arnold.

Despite his early success, Bannister still faced challenges because of racism in the U.S.. After slavery ended, the abolitionist groups began to break up, and with them, some of his support. An article in the New York Herald reportedly said that Black people could appreciate art but couldn't create it. This made Bannister even more determined to succeed as an artist.

Success in Providence

With Christiana's support, Bannister became a full-time painter in 1870, after they moved to Providence, Rhode Island. He got a studio and became friends with other artists there. He started painting more landscapes and won an award in 1872 for his painting Summer Afternoon. He also began showing his paintings at the Boston Art Club.

Bannister gained national fame when he won first prize for his large oil painting Under the Oaks at the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial. The judges wanted to take back the award when they found out he was Black. But other artists at the exhibition protested, and Bannister kept his prize. He said he was proud that the jury didn't know anything about his race when they gave him the award. Bannister had purposely submitted his painting with only his signature to make sure he was judged fairly.

As his career grew, he received more jobs and honors. He won silver medals in 1881 and 1884 from the Massachusetts Charitable Mechanic Association. Important art collectors also bought his work.

In 1878, Bannister became an original board member of the Rhode Island School of Design. In 1880, he and other artists and collectors started the Providence Art Club to encourage art appreciation in the community. Their first meeting was in Bannister's studio. He was one of the first to sign the club's founding document and taught art classes there. He continued to show his paintings in Boston, Connecticut, and New York. He also showed A New England Hillside at the New Orleans Cotton Exposition in 1885. However, his work there was separated from others and ignored by the judges because of his race. Because of this, Bannister decided not to submit any paintings to the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition.

In the 1880s, Bannister bought a small sailboat called the Fanchon. He spent summers sketching, painting watercolors, and sailing around Narragansett Bay and up to Bar Harbor in Maine. He would use these sketches to create larger paintings in the winter. He also traveled to art exhibitions in New York, but he couldn't afford a planned trip to Europe.

In 1885, Bannister helped found the Anne Eliza Club, a men's discussion group. Through his teaching at this club and the Providence Art Club, he became a mentor to younger artists. One artist, Charles Walter Stetson, often wrote about Bannister in his diaries, calling him his "only confidant in Art matters."

Bannister and Christiana were active members of the African American community in Providence. Christiana founded the Home for Aged Colored Women, which is now called the Bannister Center. Edward showed his painting Christ Healing the Sick there in 1892 and donated his portrait of Christiana to the home. Even though he was respected at the Providence Art Club, his anti-slavery views likely caused some disagreements with the mostly white members.

Around 1890, Bannister sold his sailboat. His biggest art show was in 1891, where he displayed 33 works at the Spring Providence Art Club Exhibition. Later in the 1890s, he seemed to sell fewer paintings and exhibited less often. In 1898, Bannister closed his studio. He and Christiana moved to Boston for a year before returning to a smaller home in Providence in 1900.

His Passing

Bannister died of a heart attack on January 9, 1901, during an evening prayer meeting at his church. He had been having heart problems but had finished two paintings just the day before. His last words were reportedly "Jesus, help me."

After his death, the Providence Art Club held an exhibition to honor him. They focused on his artistic achievements but did not mention his work against slavery. In the exhibition pamphlet, they praised his kind nature and his love for painting natural scenes.

He is buried in the North Burial Ground in Providence, under a stone monument designed by his artist friends. His friend John Nelson Arnold noted the difference between Bannister's financial struggles at the end of his life and the grand memorial after his death.

Christiana was admitted to her Home for Aged Colored Women in 1902 and died in 1903. She and Edward are buried together.

His Unique Art Style

Bannister started as a portrait painter, but he became famous for his landscapes and seascapes. He also painted scenes from the Bible, myths, and everyday life. His work showed the influence of French Barbizon painters like Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot. Bannister believed that making art was a very spiritual practice.

Some historians have also seen the influence of the Hudson River School in his work. However, unlike those artists, Bannister didn't create super detailed landscapes. He focused more on the large, revealing shapes of trees and mountains. He also avoided the grand, nationalistic feeling often found in Hudson River School paintings.

Bannister often made pencil or pastel sketches before creating his larger oil paintings. His paintings are known for their delicate use of color to show shadows and atmosphere, and for his loose brushwork. His later paintings used lighter, softer colors. For example, the Boston Common scene he painted late in his life is a notable example. This change in style is interesting because he had earlier said he didn't like Impressionist painting.

Even though Bannister was dedicated to freedom and equal rights for African Americans, he didn't often show these issues directly in his paintings. However, some of his paintings, like Hay Gatherers, subtly showed racial issues. This painting shows African American farm workers in a rural landscape. Unlike his usual peaceful scenes, Hay Gatherers hints at the struggles of labor and racial oppression in Rhode Island.

Bannister often used symbols and hints to convey political meaning in his art. His early painting, The Ship Outward Bound, might have been a hidden reference to the forced return of Anthony Burns to slavery in 1854. In African American culture, a ship leaving a harbor could remind people of the Atlantic slave trade.

Some critics have said that Bannister didn't often directly show African Americans in his paintings, except for his early portraits. His work appealed to a wider audience, including white patrons, which was important for his career. Art historian Juanita Holland explained that Black artists faced a challenge: they needed to show African American identity while also creating art that white viewers could appreciate in a universal way.

Bannister's Lasting Impact

Bannister was a unique African American artist of the late 1800s because he developed his skills without studying in Europe. He was well-known in Providence and admired by artists across the East Coast. After his death, he was largely forgotten for almost a century, mainly due to racial prejudice. His art was often left out of art history books, and his calm landscape style also went out of fashion.

However, his art is now seen as an important part of the story of African American culture and the landscapes of America after the Civil War.

His art continued to be supported by galleries. After the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s, his work was celebrated again and widely collected. In 1973, the National Museum of African Art held an exhibition about him. The Rhode Island Heritage Hall of Fame welcomed Bannister in 1976.

In September 2017, a street in Providence was renamed Bannister Street to honor Edward and Christiana Bannister. In May 2021, the Providence Art Club unveiled a bronze statue of Bannister.

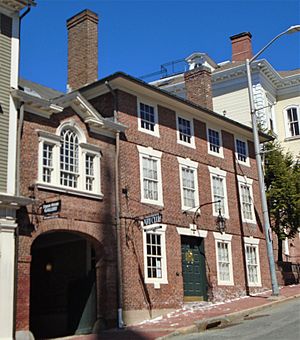

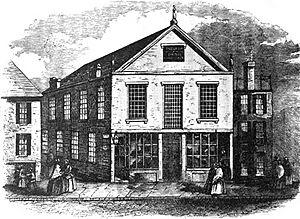

The Bannister House

In 1884, Bannister and Christiana moved to a house at 93 Benevolent Street, where they lived until 1899. This two-and-a-half-story wooden house is now known as "The Vault" or "The Bannister House." Later owners renovated it, adding a brick exterior.

The house is now recognized as an important historical building in the College Hill Historic District. Brown University bought the property in 1989. For a while, the house was in disrepair. In 2001, the Providence Preservation Society listed it as one of the most endangered buildings in Providence.

Brown University later renovated the house in 2015, bringing it back to its original look. It was sold in 2016 as part of a special home ownership program.

Important Artworks

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Edward Mitchell Bannister para niños

In Spanish: Edward Mitchell Bannister para niños

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |