Robert Gould Shaw facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Robert Gould Shaw

|

|

|---|---|

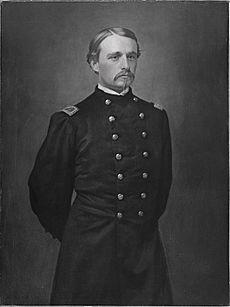

Shaw in May 1863

|

|

| Born | October 10, 1837 Dartmouth, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Died | July 18, 1863 (aged 25) Charleston County, South Carolina, U.S. |

| Place of burial | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ |

|

| Years of service | 1861–1863 |

| Rank | |

| Unit | 7th New York Militia 2nd Regiment Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry |

| Commands held | 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War: |

Robert Gould Shaw (born October 10, 1837 – died July 18, 1863) was an American officer. He served in the Union Army during the American Civil War. Shaw came from a well-known family in Boston who were abolitionists. This meant they strongly believed in ending slavery.

He took command of the 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment. This was the first all-Black regiment in the Northeast. Shaw supported his troops and wanted them to be treated fairly. He even encouraged them to refuse their pay until it was the same as what white soldiers earned.

Colonel Shaw led his regiment in the Second Battle of Fort Wagner in July 1863. They attacked a fort near Charleston, South Carolina. Shaw was shot and killed while leading his men. Even though the regiment faced heavy fire and had many losses, Shaw's bravery and his regiment became famous. Their actions inspired many thousands more African Americans to join the Union Army. This helped the Union win the war.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Shaw was born in Dartmouth, Massachusetts. His parents, Francis George and Sarah Blake (Sturgis) Shaw, were famous abolitionists. They were also known for helping others and for their smart ideas. The family had a lot of money from Shaw's grandfather. Robert had four sisters: Anna, Josephine, Susanna, and Ellen.

When Robert was five, his family moved to West Roxbury. He later traveled and studied in Europe for several years. In 1847, his family moved to Staten Island, New York. They lived among writers and abolitionists there. Shaw went to school at the Second Division of St. John's College (now Fordham Preparatory School).

In 1851, Shaw's uncle died. Shaw found it hard to get used to his new schools. He studied Latin, Greek, French, and Spanish. He also played the violin. In late 1851, Shaw left St. John's. His family then went on a long trip to Europe. Shaw attended a boarding school in Neuchâtel, Switzerland, for two years. After that, he went to a school in Hanover, Germany. His father hoped this school would be better for him.

While Shaw was studying in Europe, Harriet Beecher Stowe published her book Uncle Tom's Cabin (1852). She was a friend of his parents and an abolitionist. Shaw read the book many times. He was deeply moved by its story and its message against slavery. Around this time, Shaw felt more patriotic. He wanted to join the West Point or the Navy. However, his parents did not think he would be good at taking orders.

Shaw returned to the United States in 1856. From 1856 to 1859, he went to Harvard University. He joined some clubs but left before graduating. After leaving Harvard in 1859, Shaw worked for his uncle's company. He found this work difficult, just like his school experiences.

Serving in the American Civil War

When the American Civil War began, Shaw joined the 7th New York Militia. In April 1861, he marched with his unit to defend Washington, D.C.. After three months, his regiment was finished. Shaw then joined a new regiment from his home state, the 2nd Massachusetts Infantry.

In May 1861, Shaw became a second lieutenant. For the next year and a half, he fought in several battles. These included the first Battle of Winchester, the Battle of Cedar Mountain, and the Battle of Antietam. Shaw was wounded twice. By late 1862, he was promoted to captain.

Since the war started, abolitionists like Massachusetts governor John Albion Andrew wanted African Americans to join the army. Many people did not agree with this idea. They thought Black troops would not be disciplined or good fighters.

Governor Andrew went to Washington, D.C., in January 1863. He met with Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton to argue for Black soldiers. Stanton agreed. On January 26, 1863, Stanton ordered Andrew to create new volunteer regiments. These could include "persons of African descent." Andrew immediately started forming the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry.

Governor Andrew wanted a strong leader for this new unit. He believed the success of this regiment would show the world the character of African Americans. Andrew wrote to many abolitionist leaders, including Shaw's father, Francis Shaw. He included an offer for Robert Shaw to command the new regiment.

Francis Shaw traveled to Virginia to talk to his son. Robert Shaw was not sure at first. He did not think the unit would fight in real battles. But he finally agreed to take the command. On February 6, he sent a telegram to his father with his decision. He was 25 years old. This command made him a colonel.

Andrew had trouble finding enough Black volunteers in Massachusetts. He promised recruits they would get the standard pay of 13 dollars a month. He also promised that if they were captured, the U.S. government would treat them like any other soldier. Two sons of the famous abolitionist Frederick Douglass joined the 54th.

Colonel Shaw arrived in Boston on February 15, 1863. He immediately started training the men. He was very strict and wanted them to be excellent soldiers.

Shaw was promoted to major in March 1863. Two weeks later, in April, he became a full colonel. By May 11, more troops had arrived than needed for the regiment. So, the 55th Massachusetts was started with the new recruits.

On May 28, Shaw led the 54th through Boston. They marched to the docks and boarded a ship. The regiment sailed south to join a Union attack on Charleston, South Carolina. The 54th arrived on June 4. They were first used for manual labor. But Colonel Shaw wanted action. Four days later, his regiment was sent to Hilton Head. From there, they moved to St. Simons Island, which was their base.

On June 11, 1863, the 54th went on a raid with another Black regiment. They went to the town of Darien, Georgia. The overall commander, Colonel James Montgomery, ordered his troops to loot the town. Shaw was very upset by this. He ordered his men to only take useful items for camp. Montgomery then said he would burn the town. Shaw felt this served no military purpose. He knew it would cause great hardship for the people living there. He told Montgomery he would not take responsibility for it. Montgomery then burned the town to the ground.

Shaw later wrote to his superiors about this. He wanted to know if Montgomery was following orders. He said he was willing to burn places that resisted. But he felt it was wrong to make women and children homeless without reason.

The Attack on Fort Wagner

Colonel Shaw and the 54th Regiment were sent to Charleston, South Carolina. They were part of a second attempt to capture Charleston. To do this, they needed to take Fort Wagner. This fort protected the southern entrance to the harbor. The fort had many strong guns and a large Confederate army defending it. The Union leaders did not realize how strong the fort was.

At the Second Battle of Fort Wagner on July 18, 1863, the 54th approached the fort in the late afternoon. They waited for a night attack. After a heavy bombing from the sea, the 54th charged forward. Shaw led his men, shouting, "Forward, Fifty-Fourth, forward!" The 54th crossed a ditch and climbed the muddy outer wall.

When the bombing stopped, the Confederate soldiers came out of their shelters. They took their positions on the walls. The 54th faced heavy fire and hesitated. Shaw climbed onto the wall and urged his men forward. He was shot three times in the chest and died early in the battle. He fell outside the fort. The fighting continued for hours. The Union forces had to retreat, suffering many losses.

Two sons of Frederick Douglass, Lewis and Charles Douglass, were with the 54th regiment during the attack. Lewis was wounded shortly after Shaw fell.

After the battle, the Confederate General Johnson Hagood returned the bodies of other Union officers. But he left Shaw's body to be buried in a mass grave with the Black soldiers. Hagood said he would have returned Shaw's body if he had commanded white troops. This was meant as an insult.

However, Shaw's friends and family saw it as an honor. They believed it was fitting for him to be buried with his soldiers. Shaw's father said he was proud his son was buried with his troops. He felt it showed his son's role as a soldier and a fighter for freedom.

After the war, the Union Army reburied all the remains, including Shaw's. They were moved to the Beaufort National Cemetery in Beaufort, South Carolina. Their gravestones were marked as "unknown."

Shaw's sword was stolen from his first grave. It was found in 1865 and returned to his parents. In 2017, it was found again in a family attic. Shaw's descendants donated it to the Massachusetts Historical Society.

Personal Life

Shaw met Anna Kneeland Haggerty in New York in 1861. They became engaged in late 1862. They married on May 2, 1863, just before Shaw's regiment moved out. The ceremony was in New York City. They had a short honeymoon at the Haggertys' home in Lenox, Massachusetts.

Anna Shaw became a widow at 28. She lived in Europe for many years after the war. She returned to her family home later in life due to poor health. She died in 1907 and never remarried. She is buried in Lenox.

Memorials and Honors

- A memorial stone is at the Mount Auburn Cemetery.

- In 1864, sculptor Edmonia Lewis created a statue of Shaw.

- The Robert Gould Shaw Memorial was revealed in Boston in May 1897. This large monument by Augustus Saint-Gaudens shows Shaw on horseback. He is with members of the 54th Regiment as they marched through Boston. This memorial was shown in the movie Glory (1989).

- A copy of the Shaw Memorial is at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C..

- A monument to Shaw is at the Moravian Cemetery in Staten Island, New York. A yearly event is held there on his birthday.

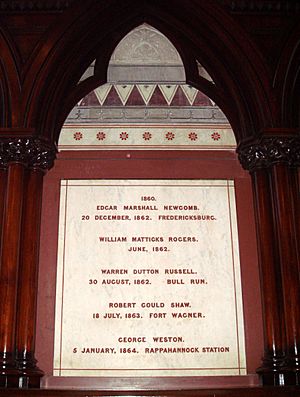

- Shaw did not graduate from Harvard College. However, his name is on the honor tablets at the university's Memorial Transept.

- Fordham University also honors Shaw as an alumnus.

- The Robert Gould Shaw School in West Roxbury, Massachusetts, opened in 1936 but is now closed.

Legacy and Recognition

- Augustus Saint-Gaudens created the famous Robert Gould Shaw Memorial in Boston. It shows Shaw leading the 54th Massachusetts Regiment. Each soldier's face and figure are shown in detail.

- The neighborhood of Shaw, Washington, D.C., was named after him. It grew from camps of freed people.

- A group called G.A.R. Post #146 was formed in 1871. It was named The R. G. Shaw Post. It was one of the first all African-American Grand Army of the Republic groups. It was made up of soldiers from the 54th Massachusetts.

- In 2017, the sword Shaw carried when he died was found in a family attic. His descendants donated it to the Massachusetts Historical Society. It was shown to the public on July 18, 2017, the anniversary of his death.

Shaw wrote over 200 letters to his family and friends during the Civil War. These letters are kept at the Houghton Library at Harvard University. You can see digital copies of these letters online. His mother published some of his letters early on. She wanted to keep his image as a hero for the abolitionist cause.

A book called Blue-Eyed Child of Fortune: The Civil War Letters of Colonel Robert Gould Shaw (1992) was edited by Russell Duncan. It includes most of Shaw's letters and a short biography.

There is an ongoing effort to give Shaw the Medal of Honor for his brave actions at Fort Wagner. This award was not given at the time because of racial discrimination.

Images for kids

Representation in Other Media

- African-American poet Paul Laurence Dunbar wrote a poem about him called "Robert Gould Shaw."

- African-American poet Benjamin Griffith Brawley wrote a poem called "My Hero" praising Shaw.

- Shaw, the 54th regiment, and the memorial are part of Charles Ives's music piece, Three Places in New England.

- New England poet Robert Lowell mentioned Shaw and the memorial in his poem "For the Union Dead."

- The film Glory (1989) is about Shaw and the 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment. Matthew Broderick played Shaw. Denzel Washington, Cary Elwes, and Morgan Freeman played soldiers in the regiment.

- Colm Toibin's novel The Master (2004) mentions Wilkie James, who was an officer in the 54th regiment.

See also

In Spanish: Robert Gould Shaw para niños

In Spanish: Robert Gould Shaw para niños

- Ventfort Hall

- Bibliography of the American Civil War

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |