Paul Laurence Dunbar facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Paul Laurence Dunbar

|

|

|---|---|

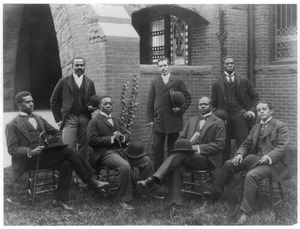

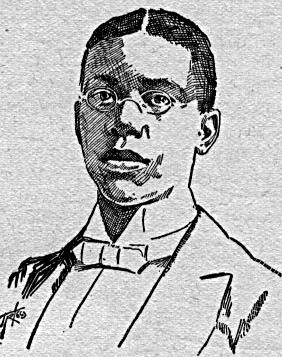

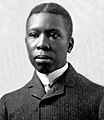

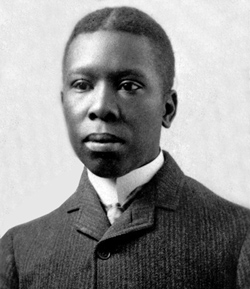

Dunbar, circa 1890

|

|

| Born | June 27, 1872 Dayton, Ohio, U.S.

|

| Died | February 9, 1906 (aged 33) Dayton, Ohio, U.S.

|

| Resting place | Woodland Cemetery, Dayton, Ohio, U.S. |

| Occupation | Poet, novelist, short story writer |

| Spouse(s) | Alice Ruth Moore |

| Signature | |

Paul Laurence Dunbar (born June 27, 1872 – died February 9, 1906) was an important American poet, writer of short stories, and novelist. He lived in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Dunbar was born in Dayton, Ohio. His parents had been enslaved in Kentucky before the American Civil War.

He started writing stories and poems when he was a child. At 16, he published his first poems in a Dayton newspaper. He was also the president of his high school's writing club.

Dunbar became very popular after a famous editor, William Dean Howells, praised his work. He was one of the first African-American writers to become famous around the world. Besides poems and stories, he wrote songs for In Dahomey (1903). This was the first musical on Broadway that was entirely created and performed by African Americans. The musical later toured in the United States and the United Kingdom.

Sadly, Dunbar suffered from tuberculosis, a serious illness that had no cure at the time. He died in Dayton, Ohio, when he was only 33 years old.

During his lifetime, many of Dunbar's popular works were written in a "Negro dialect." This was a way of writing that sounded like how people spoke in the Southern United States before the Civil War. He also wrote in a Midwestern dialect, like the poet James Whitcomb Riley. Dunbar also wrote many poems and novels in standard English. He is known as the first important African-American writer of sonnets. Today, many scholars are very interested in all his different types of writing.

Contents

Biography of Paul Laurence Dunbar

Early Life and Education

Paul Laurence Dunbar was born in Dayton, Ohio, on June 27, 1872. His parents had been enslaved in Kentucky before the American Civil War. After gaining their freedom, his mother, Matilda, moved to Dayton. Dunbar's father, Joshua, escaped slavery and joined the 55th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment. This was one of the first black army units in the war.

Paul Dunbar was born six months after his parents married. His parents' marriage was difficult, and his mother left his father soon after their second child was born. Joshua died when Paul was 13 years old.

Dunbar wrote his first poem at age six and gave his first public reading at age nine. His mother helped him with his schooling. She learned to read just to help him. She often read the Bible with him and hoped he would become a minister.

Dunbar was the only African-American student at Central High School in Dayton. Orville Wright, one of the famous Wright brothers, was his classmate and friend. Dunbar was well-liked and became president of the school's literary society. He also edited the school newspaper and joined the debate club.

Starting His Writing Career

When he was 16, Dunbar published his poems "Our Martyred Soldiers" and "On The River" in The Herald newspaper in Dayton in 1888. In 1890, Dunbar wrote and edited The Tattler. This was Dayton's first weekly newspaper for African Americans. It was printed by the new company of his high school friends, Wilbur and Orville Wright. The newspaper only lasted for six weeks.

After finishing school in 1891, Dunbar worked as an elevator operator. He earned four dollars a week. He wanted to study law, but his mother's finances were limited. He also faced racial discrimination at work.

In 1892, Dunbar asked the Wright brothers to print his dialect poems as a book. They did not have the right equipment for books. They suggested he go to the United Brethren Publishing House. In 1893, this company printed Dunbar's first poetry collection, Oak and Ivy. Dunbar paid for the printing himself. He quickly earned his money back in two weeks by selling copies to people, often on his elevator.

The book had two parts. The Oak section had traditional poems. The Ivy section had lighter poems written in dialect. This book caught the attention of James Whitcomb Riley, a popular poet. Both Riley and Dunbar wrote poems in standard English and in dialect.

People recognized Dunbar's talent. Older men offered to help him financially. A lawyer named Charles A. Thatcher offered to pay for college. But Dunbar wanted to keep writing because his poetry was selling well. Thatcher helped Dunbar by arranging for him to read his poems in Toledo, Ohio, at libraries and literary events.

A doctor named Henry A. Tobey also helped Dunbar. He helped distribute Dunbar's first book in Toledo and sometimes gave him money. Together, Thatcher and Tobey supported the printing of Dunbar's second poetry collection, Majors and Minors (1896).

Even though he published poems often and gave public readings, Dunbar found it hard to support himself and his mother. Many of his efforts were unpaid, and he spent money quickly. This left him in debt by the mid-1890s.

On June 27, 1896, a famous writer and critic, William Dean Howells, wrote a positive review of Dunbar's second book, Majors and Minors, in Harper's Weekly. Howells' praise brought national attention to Dunbar's writing. Howells liked Dunbar's traditional poems, but he especially praised the dialect poems. During this time, people appreciated folk culture, and black dialect was seen as a part of that.

This new fame allowed Dunbar to publish his first two books together in one volume. It was called Lyrics of Lowly Life and included an introduction by Howells.

Dunbar remained friends with the Wright brothers throughout his life. Through his poetry, he met and became connected with important black leaders like Frederick Douglass and Booker T. Washington. He was also close to his fellow writer James D. Corrothers. Dunbar also became friends with Brand Whitlock, a journalist who later had a political career.

By the late 1890s, Dunbar began writing short stories and novels. In his novels, he often wrote about white characters and their lives.

Later Works and Achievements

Dunbar wrote a lot during his short life. He published 12 books of poetry, four books of short stories, four novels, songs for a musical, and a play.

His first collection of short stories, Folks From Dixie (1898), received good reviews. These stories sometimes showed the harshness of racial prejudice.

His first novel, The Uncalled (1898), was not as popular. Critics said it was "dull and unconvincing." With this novel, Dunbar was one of the first African Americans to write a book only about white society. The novel was not a big commercial success.

Dunbar's next two novels also explored the lives of white people. Some critics at the time found these lacking too. However, one of these, The Sport of the Gods, is now seen as an important story about how shame can affect justice.

Dunbar wrote the songs for In Dahomey with composer Will Marion Cook and writer Jesse A. Shipp. This was the first musical written and performed entirely by African Americans. It opened on Broadway in 1903. The musical was very successful and toured England and the United States for four years. It was one of the most popular plays of its time.

Dunbar's essays and poems were published in many leading magazines. These included Harper's Weekly, Saturday Evening Post, and others. During his life, people often noticed that Dunbar looked purely African. This was at a time when many leading African Americans had mixed European and African heritage.

In 1897, Dunbar traveled to England for a literary tour. He read his works in London. He met a young black composer named Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, who set some of Dunbar's poems to music. Coleridge-Taylor was inspired by Dunbar to use African and American Negro songs in his future music.

An African-American playwright, Henry Francis Downing, also lived in London. He arranged a joint reading for Dunbar and Coleridge-Taylor. This event was supported by John Hay, who was the American ambassador to Great Britain. Downing also let Dunbar stay at his home in London while the poet worked on his first novel, The Uncalled.

Dunbar was also active in civil rights and helping African Americans. He attended a meeting on March 5, 1897, to honor the memory of Frederick Douglass. At this meeting, people worked to create the American Negro Academy.

Marriage and Health Challenges

After returning from the United Kingdom, Dunbar married Alice Ruth Moore on March 6, 1898. She was a teacher and poet from New Orleans. He had met her three years earlier. Dunbar called her "the sweetest, smartest little girl I ever saw." Alice was known for her short story collection, Violets. She and her husband also wrote poetry books together. A play called Oak and Ivy (2001) showed their love and marriage.

In October 1897, Dunbar started a job at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. He and his wife moved to the capital. They lived in the nice LeDroit Park neighborhood. His wife encouraged him to leave the job soon after to focus on his writing. He promoted his writing by giving public readings. While in Washington, D.C., Dunbar attended Howard University after his book Lyrics of Lowly Life was published.

In 1900, he was diagnosed with tuberculosis. At that time, this disease was often deadly. His doctors advised him to move to Colorado with his wife. They believed the cold, dry mountain air would be good for TB patients.

Dunbar returned to Dayton in 1904 to be with his mother. He died from tuberculosis on February 9, 1906, at the age of 33. He was buried in the Woodland Cemetery in Dayton.

Dunbar's Literary Style

Using Different Dialects

Dunbar wrote much of his work in standard English. However, he also used African-American dialect for some of his poems. He also used other regional dialects. Dunbar sometimes felt unsure about how popular his dialect poems were. He worried it might make it seem like black writers were limited to a certain way of speaking, not like educated people.

One interviewer said Dunbar told him, "I am tired, so tired of dialect." But he also said, "my natural speech is dialect" and "my love is for the Negro pieces."

Dunbar gave credit to William Dean Howells for helping him become successful early on. But he was also upset that Howells encouraged him to focus on dialect poetry. Dunbar was angry that editors refused to print his more traditional poems. He accused Howells of causing him "irrevocable harm" by pushing his dialect verse. Dunbar was part of a writing tradition that used Negro dialect. Other writers like Mark Twain and Joel Chandler Harris also used it.

Here are two short examples of Dunbar's work. The first is in standard English, and the second is in dialect. They show how different his poems could be:

(From "Dreams")

- What dreams we have and how they fly

- Like rosy clouds across the sky;

- Of wealth, of fame, of sure success,

- Of love that comes to cheer and bless;

- And how they wither, how they fade,

- The waning wealth, the jilting jade —

- The fame that for a moment gleams,

- Then flies forever, — dreams, ah — dreams!

(From "A Warm Day In Winter")

- "Sunshine on de medders,

- Greenness on de way;

- Dat's de blessed reason

- I sing all de day."

- Look hyeah! What you axing'?

- What meks me so merry?

- 'Spect to see me sighin'

- W'en hit's wa'm in Febawary?

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Paul Laurence Dunbar para niños

In Spanish: Paul Laurence Dunbar para niños

- "Ode to Ethiopia", one poem in the collection Oak and Ivy.

- African-American literature

- Dayton Aviation Heritage National Historical Park

- Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, black composer

| Leon Lynch |

| Milton P. Webster |

| Ferdinand Smith |