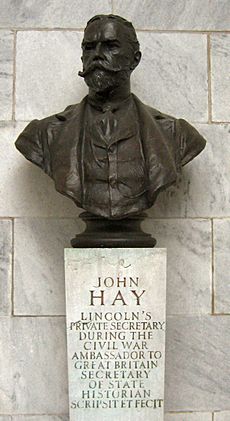

John Hay facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

John Hay

|

|

|---|---|

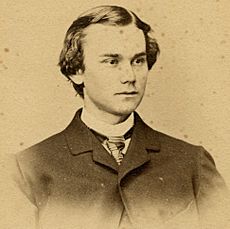

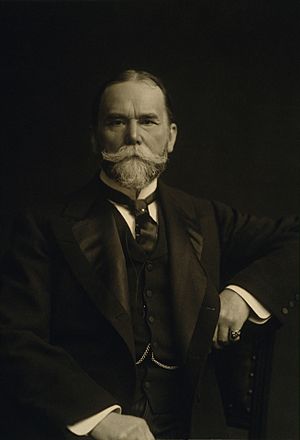

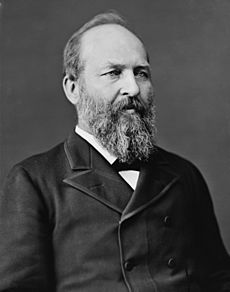

Hay in 1897

|

|

| 37th United States Secretary of State | |

| In office September 30, 1898 – July 1, 1905 |

|

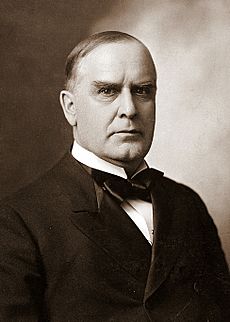

| President | |

| Preceded by | William R. Day |

| Succeeded by | Elihu Root |

| United States Ambassador to the United Kingdom | |

| In office May 3, 1897 – September 12, 1898 |

|

| President | William McKinley |

| Preceded by | Thomas F. Bayard |

| Succeeded by | Joseph Hodges Choate |

| 12th United States Assistant Secretary of State | |

| In office November 1, 1879 – May 3, 1881 |

|

| President | |

| Preceded by | Frederick W. Seward |

| Succeeded by | Robert R. Hitt |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

John Milton Hay

October 8, 1838 Salem, Indiana, U.S. |

| Died | July 1, 1905 (aged 66) Newbury, New Hampshire, U.S. |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse |

Clara Stone

(m. 1874) |

| Children | 4, including Helen and Adelbert |

| Education | Brown University (AB, MA) |

| Signature |  |

| Military service | |

| Branch/service | United States Army (Union Army) |

| Rank | Brevet Colonel |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War |

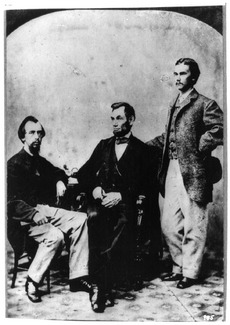

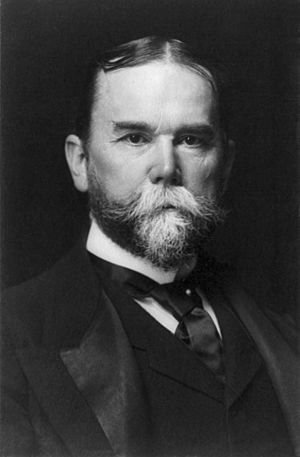

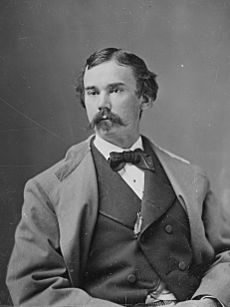

John Milton Hay (born October 8, 1838 – died July 1, 1905) was an important American leader. He worked in government for nearly 50 years. He started as a private secretary to President Abraham Lincoln. Later, he became a diplomat and served as United States Secretary of State for Presidents William McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt. Hay also wrote books about Lincoln, and he was a poet.

John Hay was born in Salem, Indiana. His family was against slavery. They later moved to Warsaw, Illinois. John was very smart, so his family sent him to Brown University. After college, he studied law. He worked for Lincoln's campaign to become president in 1860. Then, he became one of Lincoln's private secretaries in the White House.

During the American Civil War, Hay was very close to President Lincoln. He was even there when Lincoln died after being shot. Hay later wrote a ten-volume book about Lincoln. This book helped shape how people remember Lincoln today.

After Lincoln's death, Hay worked as a diplomat in Europe. He then became a journalist for the New-York Tribune. From 1879 to 1881, he was the United States Assistant Secretary of State. He then left government for a while. In 1897, President McKinley made him the United States Ambassador to the United Kingdom. The next year, he became Secretary of State.

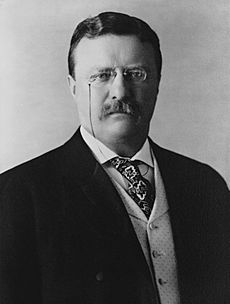

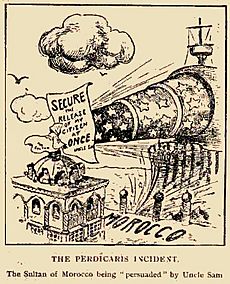

Hay served as Secretary of State for almost seven years. He worked for President McKinley and then for Theodore Roosevelt. He helped create the Open Door Policy. This policy made sure all countries could trade equally with China. Hay also helped make way for the Panama Canal. He did this by negotiating important treaties with the United Kingdom, Colombia, and the new country of Panama.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Family and Childhood

John Milton Hay was born in Salem, Indiana, on October 8, 1838. He was the third son of Dr. Charles Hay and Helen Leonard. Charles Hay was from Lexington, Kentucky. He disliked slavery and moved north in the 1830s. Helen's family moved west from Massachusetts. She became a teacher in Salem. Charles and Helen married in 1831.

His family moved to Warsaw, Illinois, in 1841. John went to local schools there. In 1849, his uncle Milton Hay invited John to live with him. John went to a good school in Pittsfield. There, he met John Nicolay, who was a newspaperman. After Pittsfield, John lived with his grandfather in Springfield. His parents and uncle Milton paid for him to go to Brown University in Rhode Island.

College and Meeting Lincoln

Hay started at Brown University in 1855. He found college life fun but also challenging. He was from the West, and his clothing and accent made him stand out. He was also often sick. Hay became known as a bright student. He was part of a group of writers in Providence. In 1858, Hay earned his Master of Arts degree. He was also the Class Poet.

After college, he returned to Illinois. His uncle Milton Hay had moved his law office to Springfield. John became a clerk there to study law. Lincoln's office was right next door. Lincoln was becoming a famous leader in the new Republican Party. Hay remembered Lincoln talking about slavery. Lincoln said that the "moral element" of slavery could not be ignored.

Hay did not support Lincoln for president at first. But after Lincoln was chosen as the Republican candidate in 1860, Hay helped him. He gave speeches and wrote newspaper articles. Nicolay, who was Lincoln's private secretary for the campaign, needed help. So, Hay worked full-time for Lincoln for six months.

After Lincoln won the election, Nicolay suggested Hay should help him at the White House. Lincoln agreed, saying, "Well, let Hay come." Hay was hired to assist Nicolay. This showed that Lincoln trusted Hay's skills.

Working for President Lincoln

Secretary in the White House

John Hay became a lawyer in Illinois in February 1861. On February 11, he traveled with President-elect Lincoln to Washington. Several Southern states had already left the Union. They formed the Confederate States of America. This was because they opposed Lincoln, who was against slavery.

When Lincoln became president on March 4, Hay and Nicolay moved into the White House. They shared a small bedroom. Hay was officially given a job in the Interior Department. But he worked at the White House. He and Nicolay were available to Lincoln 24 hours a day. Lincoln worked seven days a week, often late into the night. This made their jobs very demanding.

Hay and Nicolay split their duties. Nicolay helped Lincoln in his office and in meetings. Hay handled the many letters. Both men tried to protect Lincoln from people who wanted to meet him. Hay was charming, so people were less upset when he denied them access to Lincoln. Hay also wrote articles for newspapers without his name on them. He made Lincoln seem like a sad, religious, and capable leader. He showed Lincoln giving his life to save the country.

Despite the hard work, Hay tried to live a normal life. He ate with Nicolay at Willard's Hotel. He went to the theater with Abraham and Mary Todd Lincoln. He also read French books. Hay was in his early 20s. He spent time with Washington's important people. The two secretaries often had disagreements with Mary Lincoln. She wanted to restore the White House.

After Lincoln's 11-year-old son Willie died in 1862, Hay became very close to Lincoln. He was like a son to the President. Hay admired Lincoln's kindness, patience, and sense of humor. Speaker of the House Galusha Grow said, "Lincoln was very much attached to him." Writer Charles G. Halpine said Lincoln "loved him as a son."

Hay and Nicolay went with Lincoln to Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. This was for the dedication of the cemetery there. Many soldiers who died at the Battle of Gettysburg were buried there. Hay's diary mentioned Lincoln's short Gettysburg Address. He said Lincoln spoke "with more grace than is his wont."

Missions for the President

Lincoln sent Hay on different missions away from the White House. In August 1861, Hay took Mary Lincoln and her children to a resort in New Jersey. This was to give Hay a needed break. The next month, Lincoln sent him to Missouri. He delivered a letter to General John C. Frémont. Frémont had angered Lincoln by freeing slaves without permission. This put Lincoln's efforts to keep the border states in the Union at risk.

In April 1863, Lincoln sent Hay to South Carolina. He was to report on the ironclad ships used to attack Charleston Harbor. Hay then went to the Florida coast. He returned to Florida in January 1864. Lincoln had announced his "Ten Percent Plan." This plan said that if 10% of a state's voters swore loyalty to the Union and supported freedom for slaves, they could form a new government. Lincoln thought Florida would be a good test. Hay was made a major and sent to see if enough men would take the oath. Hay spent a month there. But Union losses reduced the area under federal control. He felt his mission was not possible, so he went back to Washington.

In July 1864, a New York publisher, Horace Greeley, told Lincoln about Southern peace messengers in Canada. Lincoln doubted they truly spoke for the Confederate President. But he sent Hay to New York. Hay was to convince Greeley to meet them and bring them to Washington. Greeley reported that the messengers could not speak for the Confederate President. But they were sure they could bring both sides together. Lincoln sent Hay to Canada with a message. It said that if the South stopped fighting, freed the slaves, and rejoined the Union, they would get good terms. The Southerners refused to come to Washington.

Lincoln's Assassination

By late 1864, Lincoln was reelected, and the war was ending. Both Hay and Nicolay wanted new jobs. After Lincoln's second inauguration in March 1865, they were appointed to the U.S. team in Paris. Hay was to be the secretary of the legation. Hay wrote that the job was "unexpected." But he had spent many hours with Secretary of State William H. Seward. Their close relationship was well known. They stayed at the White House until their replacements arrived.

Hay was not with the Lincolns at Ford's Theatre on April 14, 1865. He was at the White House with Robert Lincoln. When they heard the President had been shot, they rushed to the Petersen House. Lincoln had been taken there. Hay stayed by Lincoln's side all night. He was there when Lincoln died. Hay saw "a look of unspeakable peace" on Lincoln's face. He heard War Secretary Edwin Stanton say, "Now he belongs to the ages."

Lincoln's death was a huge personal loss for Hay. He felt it was like losing a father. Lincoln's death made Hay sure of Lincoln's greatness. In 1866, Hay called Lincoln "the greatest character since Christ." Hay would spend the rest of his life remembering Lincoln.

Early Diplomatic Career

Hay went to Paris in June 1865. He worked under U.S. Minister to France John Bigelow. The work was not hard, and Hay enjoyed Paris. When Bigelow resigned, Hay also resigned. He stayed until January 1867. He asked Secretary of State Seward for another good job. Seward suggested being Minister to Sweden. But President Andrew Johnson had his own choice. Seward offered Hay a job as his private secretary, but Hay said no. He went home to Warsaw, Illinois.

Hay soon felt restless at home. In June 1867, he was happy to hear he was appointed secretary of legation in Vienna. He sailed to Europe that month. In England, he was very impressed by Benjamin Disraeli. The Vienna job was temporary and the work was light. Hay spoke German well, so he traveled a lot. He resigned in July 1868 and spent the summer in Europe. Then he went home to Warsaw.

In December 1868, Hay went to Washington. He was looking for a good job. Seward promised to help him. But nothing happened before Seward and Johnson left office in March 1869. In May, Hay went back to Washington to ask the new Grant administration for a job. In June, he got the job of secretary of legation in Spain.

The salary was low in Madrid. But Hay was interested because of the political situation there. Queen Isabella II had recently been removed from power. Hay hoped to help the U.S. gain control over Cuba, which was a Spanish colony. Hay resigned in May 1870 due to the low salary. He stayed until September. From his time in Madrid, he wrote magazine articles. These became his first book, Castilian Days. He also became lifelong friends with Alvey A. Adee, who would later help Hay at the State Department.

Life Outside Government

Journalism and Marriage

While still in Spain, Hay was offered a job at the New-York Tribune. He became an assistant editor in October 1870. The Tribune was a leading newspaper in New York. It had the largest circulation in the country. Hay wrote editorials for the paper. The editor, Horace Greeley, said Hay was a brilliant writer.

Hay's work grew. In October 1871, he went to Chicago after the great fire. He interviewed Catherine O'Leary, whose cow was said to have started the fire. Hay's fame as a poet was growing. A colleague said it was a joy to work with John Hay. Besides writing, Hay gave lectures about democracy in Europe. He also spoke about his years in the Lincoln White House.

By 1873, Hay was dating Clara Stone. She was the daughter of a very rich railroad and banking owner from Cleveland, Amasa Stone. They married in 1874. This made money less of a concern for Hay. Amasa Stone wanted Hay to manage his investments. So, Hay moved to Cleveland in June 1875. The Hays had four children: Helen Hay Whitney, Adelbert Stone Hay, Alice Evelyn Hay Wadsworth Boyd, and Clarence Leonard Hay. Hay was good at managing money. But he spent much of his time on writing and politics.

In 1876, a bridge collapsed over Ohio's Ashtabula River. It was built from metal from one of Stone's factories. It was carrying a train owned by Stone's company. Ninety-two people died. It was the worst train disaster in American history at that time. People blamed Stone. He went to Europe, leaving Hay in charge of his businesses. The summer of 1877 had many labor strikes. Hay was very angry about these strikes. He blamed foreign troublemakers. He wrote about his anger in his only novel, The Bread-Winners (1883).

Return to Politics

Hay was not happy with the Republican Party in the mid-1870s. He wanted a reformer to be president. He supported Samuel Tilden, a Democrat. But he also liked Republican James G. Blaine. Blaine did not get the nomination. Instead, Ohio Governor Rutherford B. Hayes won. Hay did not support Hayes. Hayes's victory left Hay out of politics.

Hay tried to get back into politics. He sent President Hayes a gold ring with a strand of George Washington's hair. Hayes liked this gift. Hay also worked with Nicolay on their Lincoln biography. He traveled in Europe. In December 1878, Whitelaw Reid, the Tribune editor, was offered a job as Minister to Germany. He turned it down and suggested Hay. But Secretary of State William M. Evarts said Hay "had not been active enough in political efforts." Hay was disappointed.

From May to October 1879, Hay worked to show he was a loyal Republican. He gave speeches and attacked Democrats. In October, President and Mrs. Hayes visited Hay's home in Cleveland. When Assistant Secretary of State Frederick W. Seward resigned, Hay was offered his job. He accepted.

In Washington, Hay managed 80 employees. He became friends again with Henry Adams. He filled in for Evarts at Cabinet meetings. In 1880, he campaigned for Republican candidate James A. Garfield. Garfield asked Hay for advice before and after his election. But Garfield only offered Hay the job of private secretary. Hay said no. Hay resigned as assistant secretary in March 1881. He then worked as acting editor of the Tribune. Garfield's death in September left Hay out of political power again. He would stay out for the next 15 years.

Wealthy Traveler and Author

After 1881, Hay did not hold public office until 1897. Amasa Stone's death in 1883 made the Hays very rich. They spent several months each year traveling in Europe. The Lincoln biography took some of Hay's time. The hardest work was done with Nicolay in 1884 and 1885. In 1886, parts of the biography began to appear. The ten-volume biography was published in 1890.

In 1884, Hay and Adams hired an architect to build them houses in Washington. These were finished by 1886. Hay's house was described as "the finest house in Washington." It cost more than twice what he planned. Despite having two fancy houses, the Hays spent less than half the year in Washington. They also spent time at The Fells, their summer home in Newbury, New Hampshire.

Hay continued to be active in Republican politics. In 1884, he supported Blaine for president. He gave a lot of money to Blaine's campaign. In 1888, Hay supported John Sherman. But Sherman did not win the Republican nomination. Hay then supported Benjamin Harrison, who was elected. Hay was not asked to join the Harrison administration. In 1890, Hay spoke for Republican candidates. But the party lost control of Congress. Hay gave money to Harrison's re-election effort.

Supporting William McKinley

Hay was an early supporter of Ohio's William McKinley. He worked closely with McKinley's political manager, Mark Hanna. In 1889, Hay supported McKinley's effort to become Speaker of the House. Four years later, McKinley faced money problems. A friend he had helped went bankrupt. Hay was among those Hanna asked for help. He bought $3,000 of the debt. McKinley never forgot Hay's kindness.

The money problems convinced Hay that people like him needed to be in government. By late 1894, he was helping McKinley's presidential campaign for 1896. Hay's job was to convince others to support McKinley. He also spent time at his New Hampshire home. He wrote a $500 check to Hanna. This was the first of many.

Hay spent part of 1896 in Europe. There was a border dispute between Venezuela and British Guiana. The U.S. supported Venezuela. Hay told British politicians that McKinley would likely continue this policy. McKinley was nominated in June 1896. Many British people supported the Democratic candidate. But this changed when William Jennings Bryan was nominated. He gave his famous Cross of Gold speech. Hay reported that the British were "scared out of their wits" that Bryan would win.

When Hay returned to the U.S. in August, he went to his New Hampshire home. He watched Bryan travel the country giving speeches. McKinley gave speeches from his home. Hay visited McKinley in October. Hay disliked Bryan's speeches. McKinley won the election easily. His campaign was well-funded by supporters like Hay.

Ambassador to the United Kingdom

Becoming Ambassador

After McKinley's election, many people wondered who would get government jobs. Hay and Whitelaw Reid both wanted high positions in the State Department. Reid was sick with asthma. He went to Arizona for the winter. This led to worries about his health.

Hay quickly realized that Mark Hanna wanted to be a senator from Ohio. Senator Sherman held the only possible seat for Hanna. Sherman would only leave his seat if he became Secretary of State. Hay knew that only one Ohioan could be in the Cabinet. So, he had no chance for a Cabinet job. Hay encouraged Reid to seek the State Department job. He quietly worked to become ambassador in London. Hay "aggressively lobbied" for the position.

Hay sent a message to McKinley. He suggested McKinley tell Reid that Reid's friends did not want him to risk his health in London's smog. The next month, Hay wrote to McKinley. He explained why he should be ambassador. He urged McKinley to act fast to find a good house in London. Hay got the job. Hanna also got his wish. Reid was upset by Hay's appointment. It almost ended their 26-year friendship.

People in Britain were generally happy about Hay's appointment. George Smalley of The Times wrote that they wanted "a man who is a true American yet not anti-English." Hay found a large house in London with 11 servants. He brought his wife, their silver, two carriages, and five horses. Hay's salary was $17,000. But this did not cover their expensive lifestyle.

His Time as Ambassador

As ambassador, Hay tried to improve the relationship between the U.S. and Britain. Many Americans had a negative view of Britain. This was because of the American Revolution and Britain's neutrality in the Civil War. But Hay believed that friendship made more sense. In a speech in London in 1897, Hay said, "The great body of people in the United States and England are friends." He said they shared a deep respect for "order, liberty, and law." Hay did not solve all problems. But both he and British leaders saw his time as a success. He helped create good feelings between the two nations.

One ongoing dispute was about hunting seals off Alaska. The U.S. said they were American resources. Canadians said the seals were in international waters. Soon after Hay arrived, McKinley sent former Secretary of State John W. Foster to London to discuss this. Foster sent an angry note to the British. Hay got Lord Salisbury, the Prime Minister, to agree to a meeting. But the British pulled out when the U.S. invited Russia and Japan.

Another issue was bimetallism. McKinley had promised to seek an international agreement on silver and gold prices. Hay was told to ask Britain to join. But Britain would only join if India agreed. This did not happen. Also, the economy improved, so support for bimetallism in the U.S. decreased. No agreement was reached.

Hay was not very involved in the crisis over Cuba. This led to the Spanish–American War. He met with Lord Salisbury in October 1897. He got assurances that Britain would not interfere if the U.S. went to war with Spain. Hay's job was to "make friends and to pass along the English point of view to Washington." Hay was in the Middle East for much of early 1898. He returned to London in March. By then, the USS Maine had exploded in Havana harbor.

During the war, Hay worked to keep the U.S. and Britain friendly. He also made sure Britain accepted the U.S. taking the Philippines. Salisbury preferred the U.S. to have the islands rather than Germany. Hay kept the British informed about the U.S. invasion of Cuba. He also told the McKinley administration about British interests in Cuba.

Hay called the war "a splendid little war." He said it began with good reasons. It was fought with great skill and spirit. He hoped it would end with "fine good nature." This, he said, was a key American trait.

Secretary Sherman had resigned before the war. William R. Day replaced him. Day had little experience in foreign policy. McKinley needed a stronger leader. On August 14, 1898, Hay got a telegram from McKinley. It said Day would lead the peace talks with Spain. Hay would be the new Secretary of State. Hay accepted. British people were happy about his promotion. Queen Victoria was very impressed with him.

Secretary of State

Under President McKinley

John Hay became Secretary of State on September 30, 1898. He quickly fit into Cabinet meetings. He sat next to the President. Hay believed that the U.S. relationship with Great Britain was the most important. He worked hard to make it positive. He often shared secret information with the British. But he kept it from other countries like Spain, France, Germany, and Russia. Senator Mark Hanna said, "Hay and McKinley are outrageously pro-British."

When Hay took office, the war was almost over. Spain was losing its overseas empire. The U.S. would take some of it. McKinley decided to take the Philippines in October. Hay sent instructions to the peace commissioners to insist on it. Spain agreed. This led to the Treaty of Paris. The Senate approved it in February 1899.

The Open Door Policy

By the 1890s, China was a big trading partner for Western countries and Japan. China's army was weak after several wars. Other countries took control of coastal cities in China. These were called treaty ports. They used them as military bases or trading centers. These countries often favored their own citizens in trade. The U.S. did not claim any parts of China. But a third of the trade with China was on American ships. Keeping the Philippines was important for trade with China.

Hay had been worried about China since the 1870s. As Ambassador, he tried to work with the British. But Britain was willing to take land in China, like Hong Kong. McKinley was not. In March 1898, Hay warned that Russia, Germany, and France wanted to exclude Britain and America from China trade. But Sherman ignored him.

McKinley believed that equal trade opportunities in China were key. He did not want to take colonies. Hay agreed with this view. Many Americans wanted McKinley to join in dividing China. But in December 1898, McKinley said that as long as Americans were treated fairly, the U.S. did not need to take part in dividing China.

As Secretary of State, Hay had to create a China policy. He was advised by William Woodville Rockhill. Rockhill was an expert on China. Charles Beresford, a British politician, also influenced Hay.

In 1899, a British official named Alfred Hippisley visited the U.S. He wrote to Rockhill. He said the U.S. and other powers should agree on fair tariffs in China. Rockhill told Hay about this idea. He said there should be "an open market through China for our trade on terms of equality." Hay agreed. But he wanted to avoid a treaty that needed Senate approval. Rockhill wrote the first Open Door note. It called for equal business chances for all foreigners in China.

Hay officially issued his Open Door note on September 6, 1899. This was not a treaty. It did not need Senate approval. Most countries agreed, but with some conditions. Negotiations continued. On March 20, 1900, Hay announced that all powers had agreed. Former Secretary Day congratulated Hay. He said Hay had achieved a "diplomatic triumph."

The Boxer Rebellion

No one thought much about how the Chinese would react to the Open Door note. The Chinese minister in Washington learned about it from newspapers. In China, a group called the Fists of Righteous Harmony, or Boxers, opposed Western influence. They were especially angry at missionaries. In June 1900, the Boxers, joined by imperial troops, cut the railroad to Peking. They killed many missionaries and surrounded foreign buildings. Hay faced a difficult situation. He needed to rescue Americans in Peking. He also wanted to stop other countries from dividing China. This was also an election year.

American troops were sent to China to help. Hay sent a letter to foreign powers. This was called the Second Open Door note. He said the U.S. wanted lives saved and guilty people punished. But it also wanted China to remain whole. Hay sent this on July 3, 1900. He suspected other powers were secretly planning to divide China. Communication with the foreign buildings had been cut. People thought everyone inside was dead. But Hay realized the Chinese minister could send a message. Hay was able to communicate with the Chinese government. He suggested they cooperate for their own good. A foreign relief force, mainly Japanese, rescued the people. China had to pay a huge amount of money. But no land was taken.

McKinley's Death

McKinley's vice president, Garret Hobart, died in November 1899. This made Hay next in line to the presidency if something happened to McKinley. In the 1900 election, McKinley was chosen again. He let the convention pick his running mate. They chose Theodore Roosevelt, who was governor of New York. Senator Hanna was against this choice. But he still raised millions for the McKinley/Roosevelt team. They won the election.

Hay went with McKinley on his train tour in 1901. They both visited California and saw the Pacific Ocean. The summer of 1901 was sad for Hay. His older son, Adelbert, died from a fall. Adelbert was about to become McKinley's personal secretary.

Secretary Hay was at his New Hampshire home when McKinley was shot on September 6 in Buffalo. Vice President Roosevelt and many Cabinet members rushed to McKinley's side. Hay planned to go to Washington to handle foreign communications. But McKinley's secretary urged him to come to Buffalo. Hay arrived on September 10. He heard McKinley was recovering. But Hay said McKinley would die. He was more cheerful after visiting McKinley. He then went to Washington. Roosevelt and others also left Buffalo. Hay was about to return to New Hampshire on September 13. Then, he heard McKinley was dying. Hay stayed at his office. The next morning, Roosevelt received Hay's first message as president. It officially told him of McKinley's death.

Under President Theodore Roosevelt

Staying in Office

Hay, again next in line to the presidency, stayed in Washington. McKinley's body was brought to the capital. Then it was taken to Canton for burial. Hay admired McKinley greatly. He called him "awfully like Lincoln." Hay wrote to a friend that it was tragic to stand by the deaths of three dear friends: Lincoln, Garfield, and McKinley. All three were presidents and killed by assassins.

Hay offered his resignation to Roosevelt. Newspapers thought Hay would be replaced. But when Hay met the funeral train in Washington, Roosevelt told him he must stay as secretary. Roosevelt's unexpected rise to president made Hay very important. He was the wise elder statesman in the Cabinet. He was essential to Roosevelt, who was the youngest president ever.

Hay suffered more sadness in 1901. His close friend John Nicolay died on September 26. His friend Clarence King died on Christmas Eve.

The Panama Canal

Hay had been involved in efforts to build a canal in Central America for a long time. This went back to his time as Assistant Secretary of State. The 1850 Clayton–Bulwer Treaty between the U.S. and Britain stopped the U.S. from building a canal it controlled alone. Hay wanted to remove this rule. But Canada, whose foreign policy Britain handled, used the canal issue to get other disputes solved.

In August 1899, the Alaska border issue became less tense. Canada accepted a temporary border. Congress wanted to start a canal project. They were likely to ignore the Clayton-Bulwer rule. Hay and British Ambassador Julian Pauncefote began working on a new treaty in January 1900. The first Hay–Pauncefote Treaty was sent to the Senate. It was not well-received. It said the U.S. could not block or fortify the canal. The Senate added an amendment to allow fortification. Hay offered to resign, but McKinley refused. The Senate approved the amended treaty. But the British did not agree to the changes.

Congress was still eager for a canal. They were ready to move forward with or without a treaty. They debated whether to use the Nicaragua or Panama route. Hay's replacement in London, Joseph Hodges Choate, negotiated a new treaty. This allowed the U.S. to fortify the canal. The second Hay–Pauncefote Treaty was approved by the Senate in December 1901.

The French company that had failed to build a canal in Panama still had rights to the route. They lowered their price. In early 1902, President Roosevelt supported the Panama route. Congress passed a law for it. In June, Roosevelt told Hay to lead talks with Colombia. Later that year, Hay began talks with Colombia's minister, Tomás Herrán. The Hay–Herrán Treaty was signed in January 1903. It gave Colombia $10 million for the right to build a canal. The U.S. Senate approved it. But in August, the Colombian Senate rejected the treaty.

Roosevelt wanted to build the canal anyway. He planned to use an older treaty with Colombia. Hay predicted a rebellion in Panama against Colombia. Philippe Bunau-Varilla, who owned rights to the Panama route, met with Hay and Roosevelt. He said a revolution was coming. He promised a Panamanian government that would be friendly to a canal. In October, Roosevelt sent Navy ships near Panama. The Panamanians revolted in November 1903. U.S. forces stopped Colombia from interfering. Bunau-Varilla became Panama's representative in Washington. He quickly negotiated the Hay–Bunau-Varilla Treaty. It was signed on November 18. It gave the U.S. the right to build the canal in a 10-mile wide zone. The U.S. would have full control over this zone. This was not ideal for the Panamanian diplomats who arrived later. But they did not dare reject it. Both nations approved the treaty. Work on the Panama Canal began in 1904.

Relationship with Roosevelt

Hay had known "Teddy" Roosevelt since he was a teenager. Roosevelt was 20 years younger than Hay. Before becoming president, Roosevelt often praised Hay. But in private, he was less complimentary. Hay felt Roosevelt was too impulsive. He privately opposed Roosevelt being on the ticket in 1900.

As President and Secretary of State, they tried to have a good relationship. Roosevelt read all ten volumes of Hay's Lincoln biography. He told Hay he was a "really great Secretary of State." Hay publicly praised Roosevelt as "young, gallant, able, [and] brilliant."

In private, they were less kind. Hay complained that McKinley gave him full attention. But Roosevelt was always busy with others. Roosevelt, after Hay's death, wrote that Hay was not "a great Secretary of State." He said Hay "accomplished little" under him. Still, when Roosevelt ran for election in 1904, he asked the aging Hay to campaign for him.

Final Months and Death

Hay never fully recovered from his son Adelbert's death. He wrote in 1904 that his son's death made him and his wife "old, at once and for the rest of our lives."

Hay gave speeches for Roosevelt in 1904. But he spent much of the fall at his New Hampshire home. After the election, Roosevelt asked Hay to stay for another four years. Hay asked for time to think. But the President announced it to the press two days later. In early 1905, many treaties Hay negotiated were defeated or changed by the Senate. This was frustrating for Hay.

By Roosevelt's inauguration in March 1905, Hay's health was very bad. His wife and friend Henry Adams insisted he go to Europe for rest and medical care. Hay hinted that he did not have long to live. A doctor in Italy prescribed baths for his heart. Hay went to Germany. Kaiser Wilhelm II and King Leopold II wanted to visit him. Adams suggested Hay retire. Hay joked that he had "nothing the matter with me except old age, the Senate, and one or two other mortal maladies."

After his treatment, Hay went to Paris. He started working again. In London, King Edward VII met with Hay in a small room. Hay also had lunch with Whitelaw Reid. There was not enough time to see everyone who wanted to meet Hay. He knew this was his last visit.

When he returned to the U.S., Hay went to Washington. He wanted to deal with work and see the President. He was happy to learn that Roosevelt was close to ending the Russo-Japanese War. Roosevelt would later win the Nobel Peace Prize for this. Hay left Washington for the last time on June 23, 1905. He arrived in New Hampshire the next day. He died there on July 1 from his heart condition. Hay was buried in Lake View Cemetery in Cleveland. Roosevelt and many other important people were there.

Literary Works

Early Writings

Hay wrote poetry while at Brown University and during the Civil War. In 1865, in Paris, he wrote "Sunrise in the Place de la Concorde." This poem criticized Napoleon III. His poem "A Triumph of Order" was about the Paris Commune. It told the story of a boy who kept his promise to be executed with other rebels.

In his poetry, Hay hoped other nations would have revolutions like the U.S. His 1871 poem, "The Prayer of the Romans," spoke of Italian history. It hoped for "One freedom, one faith without fetters,/One republic in Italy free!" His time in Vienna led to "The Curse of Hungary." In this poem, Hay predicted the end of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. After Hay's death, William Dean Howells said Hay's European poems showed American sympathy for the oppressed.

Castilian Days was a book of 17 essays about Spanish history and customs. It was first published in 1871. Hay described the Spanish as suffering from "crown, crozier, and saber." He hoped for a republican movement in Spain. This book was very popular.

Pike County Ballads, a group of six poems, brought him great success in 1871. They were written in the dialect of Pike County, Illinois, where Hay went to school. The poem "Jim Bludso" was very popular. It was about a boatman who was "no saint." But when his steamboat caught fire, he held it to the riverbank. He saved all the passengers, but died himself. Hay's poem said, "And Christ ain't a-going to be too hard/On a man that died for men." Some religious leaders were offended. But the poem was widely printed.

The Bread-Winners

The Bread-Winners was one of the first novels to be against labor unions. It was published without Hay's name in 1883. Hay may have tried to hide his writing style. The book looked at two conflicts: between business owners and workers, and between new rich people and old rich people. Hay was influenced by the labor strikes of the 1870s. These strikes affected his father-in-law's businesses. Hay was in charge at the time. Historian Scott Dalrymple said Hay wrote a very strong criticism of organized labor. He did not dare put his name on it.

The main character is Arthur Farnham. He is a rich Civil War veteran, likely based on Hay. Farnham inherited money. But he does not have much power in local politics. The villain is Andrew Jackson Offitt. He leads the "Bread-winners," a labor group that starts a violent strike. A group of veterans led by Farnham restores peace. At the end, Farnham seems likely to marry Alice Belding, a woman from his own social class.

The book was unusual because it showed the perspective of the wealthy. It was very successful and got many good reviews. But it was also criticized as being against labor and favoring the rich. Many people guessed who wrote it. This guessing helped sell more copies.

Lincoln Biography

Early in Lincoln's presidency, Hay and Nicolay asked to write his biography. Lincoln agreed. By 1872, Hay felt they should start working on it. Robert Lincoln formally agreed in 1874 to let them use his father's papers. By 1875, they were doing research. Hay and Nicolay had special access to Lincoln's papers. No other researchers could see them until 1947. They collected many documents and books about the Civil War. They sometimes used their memories. But mostly, they relied on research.

Hay began writing his part in 1876. The work was stopped by illnesses or by Hay writing The Bread-Winners. By 1885, Hay finished the chapters on Lincoln's early life. Robert Lincoln approved them. Selling the rights to The Century magazine helped them finish the huge project.

The published work, Abraham Lincoln: A History, had ten volumes. It alternated between Lincoln's life and discussions of events like battles. The first part was published in November 1886. It received good reviews. When the ten-volume set came out in 1890, it was sold door-to-door. This was common then. Despite costing $50, 5,000 copies were quickly sold. The books helped create the modern view of Lincoln as a great war leader. They showed him as more important than his helpers like Seward. Historian Joshua Zeitz said it is easy to forget how underrated Lincoln was when he died. Hay and Nicolay succeeded in making him more important in history.

Legacy and Impact

In 1902, Hay wrote that when he died, "I shall not be much missed except by my wife." But he died young, at 66. Most of his friends outlived him. His friend Henry Adams blamed the stress of Hay's job for his death. But Adams admitted Hay stayed because he feared being bored. Adams remembered Hay in his book The Education of Henry Adams. He said his own education ended with Hay's death.

Hay achieved a lot in international relations. The world may be better because of his work as Secretary of State. He was also a brilliant ambassador. But after marrying the wealthy Clara Stone, Hay sometimes chose an easy life over hard work. Despite his writing achievements, Hay was "often lazy." His first poems were his best.

Hay helped the United States act with good manners on the world stage. He was the "adult in charge" when the nation became a global power. John St. Loe Strachey said, "All that the world saw was a great gentleman and a great statesman doing his work... with perfect taste, perfect good sense, and perfect good humour."

Hay's efforts to shape Lincoln's image also made him more famous. People wanted to know what Lincoln was like from him. Their ten-volume biography has been very influential. Later biographers like Carl Sandburg did not change the main story told by Hay and Nicolay. Americans today understand Abraham Lincoln much as Hay and Nicolay wanted them to.

Hay helped create more than 50 treaties. These included the Canal treaties. He also helped settle the Samoan dispute. This led to the U.S. getting American Samoa. In 1900, Hay negotiated a treaty with Denmark. It was for the U.S. to buy the Danish West Indies. But that treaty failed in the Danish parliament.

Mount Hay on the Canada–United States border was named after John Hay in 1923. This was to honor his role in the Alaska Boundary Tribunal treaty. Brown University's John Hay Library is also named for him. Hay's New Hampshire estate, The Fells, has been preserved. The Hay-McKinney House in Cleveland reminds people of John Hay's long service. During World War II, the Liberty ship SS John Hay was named after him. Camp John Hay, a U.S. military base in the Philippines, was also named for him.

Historian Lewis L. Gould said Hay was one of the most entertaining letter writers in the State Department. His name is forever linked with the Open Door Policy in Asia. He also greatly helped solve long-standing problems with the British. Hay was patient, careful, and fair. He deserves to be seen as one of the best Secretaries of State.

See also

In Spanish: John Milton Hay para niños

In Spanish: John Milton Hay para niños

| Precious Adams |

| Lauren Anderson |

| Janet Collins |