History of U.S. foreign policy, 1897–1913 facts for kids

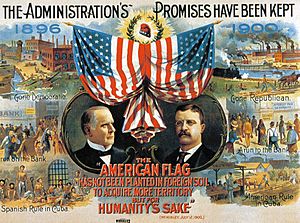

The history of U.S. foreign policy from 1897 to 1913 covers how the United States dealt with other countries during the presidencies of William McKinley, Theodore Roosevelt, and William Howard Taft. This time period came after the earlier foreign policy era and ended just before World War I began in 1914.

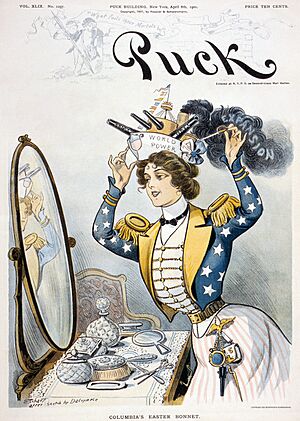

During these years, the U.S. became a major world power. It started getting involved in places far beyond its usual focus in the Western Hemisphere. Big events included the Spanish–American War, taking over Hawaii and Puerto Rico, and temporarily controlling the Philippines. The U.S. also created the Roosevelt Corollary to guide its actions in Latin America. It built the Panama Canal and sent the Great White Fleet around the world to show off its strong new Navy.

The Cuban War of Independence against Spain started in 1895. Many Americans were upset by Spain's harsh actions and wanted the U.S. government to step in. Things became very serious when the USS Maine battleship exploded in Havana harbor in 1898. President McKinley asked Spain to ease its control over Cuba, but Spain refused. McKinley then let Congress decide, and Congress declared war in April 1898.

The United States quickly won the Spanish–American War. It gained control of Spanish lands like Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines. After the war, Cuba became a country that the U.S. protected. The U.S. also had to fight a rebellion in the Philippines. Because some senators disagreed, McKinley couldn't officially annex Hawaii with a treaty. Instead, he used a special resolution in 1898 to make Hawaii a U.S. territory. This gave the U.S. an important military base in the Pacific Ocean. This period marked the start of the first overseas empire for the United States.

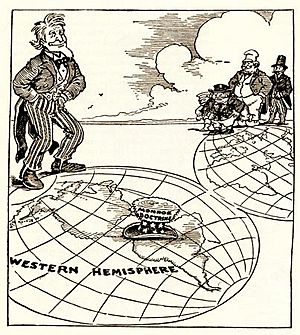

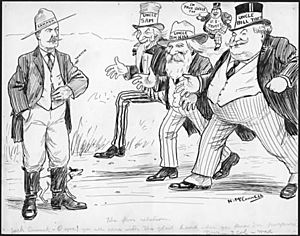

President Roosevelt wanted to keep expanding U.S. influence. He focused on making the small U.S. Army stronger and building a much larger Navy. Roosevelt also worked to improve relations with Britain. He introduced the Roosevelt Corollary, which said the U.S. would step in to manage the money problems of unstable Caribbean and Central American countries. This was to prevent European countries from getting involved directly. This policy led to several U.S. interventions in Latin America, known as the Banana Wars.

When Colombia refused a treaty to let the U.S. build a canal across Panama, Roosevelt supported Panama's independence. He then signed a treaty with Panama to create the Panama Canal Zone. The Panama Canal was finished in 1914. It greatly reduced travel time between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. Roosevelt's actions were very popular. President Taft, on the other hand, worked more quietly. He pursued "Dollar Diplomacy," which focused on using U.S. financial power in Asia and Latin America. However, Taft's efforts didn't have much success.

The Open Door Policy under President McKinley and Secretary of State John Hay guided U.S. policy toward China. This policy aimed to keep trade opportunities in China open and equal for all countries. Roosevelt helped end the Russo-Japanese War by mediating a peace treaty. He also reached the Gentlemen's Agreement of 1907 to limit Japanese immigration. Roosevelt and Taft tried to settle other international disagreements peacefully. For example, in 1906, Roosevelt helped solve the First Moroccan Crisis at the Algeciras Conference. The Mexican Revolution began in 1910. Dealing with unrest at the border was a challenge for Taft's government.

Contents

- Leaders and Their Teams

- How the U.S. Connected with the World

- Taking Over Hawaii

- The Spanish–American War

- After the Spanish–American War

- Roosevelt as President

- Better Relations with Great Britain

- Venezuela and the Roosevelt Corollary

- The Panama Canal

- Solving Disputes Peacefully

- Dollar Diplomacy in Action

- The Mexican Revolution

- Relations with Japan (1897–1913)

- Relations with China (1897–1913)

- Relations with France

- Images for kids

Leaders and Their Teams

McKinley's Presidency (1897–1901)

President McKinley took office in 1897. His first Secretary of State, John Sherman, was elderly and not very effective. McKinley's friend, William R. Day, often handled important diplomatic matters. Later, John Hay, an experienced diplomat, became Secretary of State.

For the Navy Department, McKinley chose John Davis Long. Long's assistant was Theodore Roosevelt, who was very eager to expand the Navy. The Secretary of War was Russell A. Alger. He was not prepared for the Spanish–American War. Because of problems in the War Department, Alger resigned in 1899. Elihu Root, a very capable leader, took his place.

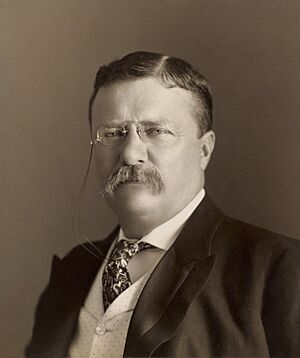

Roosevelt's Presidency (1901–1909)

McKinley was assassinated in September 1901, and Vice President Theodore Roosevelt became president. Roosevelt had strong ideas about foreign policy. He wanted the U.S. to be a major player in world affairs. He kept most of McKinley's cabinet members, including Secretary of State John Hay and Secretary of War Elihu Root. Root was a close friend and advisor to Roosevelt.

When Root left in 1904, William Howard Taft became Secretary of War. Taft had been the governor of the Philippines. Roosevelt trusted Taft's advice on many foreign policy issues. After John Hay died in 1905, Root returned to the cabinet as Secretary of State. He stayed in this role until Roosevelt's presidency ended.

Taft's Presidency (1909–1913)

Roosevelt chose not to run for president again in 1908. He strongly supported his Secretary of War, William Howard Taft. Taft easily won the 1908 election. Taft chose Philander C. Knox as his Secretary of State. Knox took full charge of diplomacy. However, he didn't get along well with the Senate or foreign diplomats.

Knox reorganized the State Department. He created new sections for different parts of the world, like the Far East and Latin America. He also started the department's first training program for new diplomats. Taft and Knox agreed on major foreign policy goals. They believed the U.S. should not get involved in European affairs. They also thought the U.S. should use force if needed to support the Monroe Doctrine in the Americas. The defense of the Panama Canal, which was still being built, guided their policy in the Caribbean.

What was Dollar Diplomacy?

Earlier presidents had tried to help American businesses overseas. But Taft went further with his policy called "Dollar Diplomacy." He used American diplomats and consuls to promote U.S. trade and investments abroad. Taft hoped these financial ties would help create world peace.

Dollar Diplomacy aimed to use American financial power instead of military force. It wanted to create a strong American interest in China. This would limit the power of other countries and open up more trade for the U.S. However, the American financial system wasn't set up for large international loans and investments. Most of Taft's efforts to get American bankers to invest overseas failed.

For example, the U.S. pushed to join an international loan for a railway in China in 1911. This loan actually helped cause a revolt against foreign investment that overthrew the Chinese government. When Woodrow Wilson became president in 1913, he immediately stopped supporting Dollar Diplomacy. Historians agree that Taft's Dollar Diplomacy was not successful. It made Japan and Russia upset and made other countries suspicious of American motives.

Taft avoided getting involved in major international events like the Agadir Crisis or the First Balkan War. However, he did support creating an international court to settle disputes. He also called for an international agreement to reduce weapons.

How the U.S. Connected with the World

American understanding of the world grew a lot during this time. Business people traveled back and forth. Big companies like J.P. Morgan and Standard Oil had operations in many countries. Tourism also became popular as travel costs dropped. The number of Americans visiting Europe jumped from 100,000 in 1885 to 250,000 by 1913.

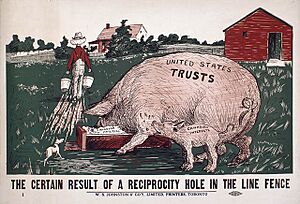

As the U.S. economy grew with new factories, American trade with other countries increased rapidly. The main trading partners were Britain, Germany, and Canada. Most countries, including the U.S., had high tariffs (taxes on imported goods) at this time. The U.S. used high tariffs to protect its growing industries and high wages for workers. In fact, American wages were so good that many skilled workers moved from Britain and Germany to the U.S.

American Protestant and Catholic churches also sponsored many missionary activities abroad. While they didn't always lead to many conversions, these missions helped spread education and modern medicine. They also worked to improve the status of women. Local churches often held events to support missions. This helped Americans learn more about the world, especially China.

Taking Over Hawaii

People in the U.S. had long wanted Hawaii to become part of the country. In the 1870s, a trade agreement made the Hawaiian Kingdom almost like a U.S. territory. In 1893, Queen Liliʻuokalani planned a new constitution to regain her power. But American business owners in Hawaii overthrew her. They asked the U.S. to annex Hawaii and later set up the Republic of Hawaii.

President Benjamin Harrison tried to annex Hawaii, but his term ended before he could get Senate approval. President Grover Cleveland then withdrew the treaty. Cleveland was against annexation because he felt it was wrong to take over a small kingdom. Some Americans also opposed it because they didn't want more Hawaiian sugar imports. Others didn't want to add an island with a large non-white population.

When McKinley became president, he made annexing Hawaii a top goal. He believed Hawaii would be a key base for the U.S. to control the Pacific, protect the West Coast, and increase trade with Asia. McKinley said, "We need Hawaii just as much and a good deal more than we did California. It is manifest destiny." He thought Hawaii couldn't survive alone and might be taken by Japan. This would hurt American trade hopes in Asia.

The idea of annexing Hawaii became a big debate across the U.S. By 1900, most Americans supported taking over both Hawaii and the Philippines. Many Americans felt it was time for the U.S. to join other world powers in gaining overseas colonies.

However, a strong group called the American Anti-Imperialist League opposed this expansion. They believed that taking over other lands went against the American idea that governments should get their power from the people they rule. They argued it would mean giving up American ideals of self-government and not interfering in other countries. Famous people like Andrew Carnegie and Mark Twain were part of this group.

But the anti-imperialists couldn't stop the push for expansion. Supporters of expansion included Secretary of State Hay and Theodore Roosevelt. They had strong backing from newspaper owners like William Randolph Hearst. These expansionists wanted a strong modern navy, bases in the Pacific, and a canal through Central America. They also warned that Japan might try to take Hawaii, which worried people on the West Coast. The U.S. Navy even started planning for a possible war with Japan.

McKinley first tried to annex Hawaii with a treaty in 1897, but it failed in the Senate. In 1898, during the Spanish–American War, McKinley tried again. He supported a resolution in Congress to annex Hawaii. Despite some opposition, the resolution passed both houses of Congress. McKinley signed it into law on July 8, 1898. In 1900, Hawaii officially became a U.S. territory.

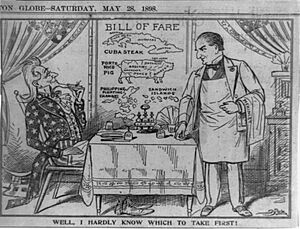

The Spanish–American War

The Cuban Problem

When McKinley became president, rebels in Cuba had been fighting for freedom from Spain for decades. By 1895, this had become a full-scale war for independence. The U.S. and Cuba had close trade ties, and the war hurt the American economy. As the fighting grew, Spain's actions became harsher. Spanish authorities moved Cuban families into guarded camps. The rebels tried to gain American sympathy, and public opinion in the U.S. increasingly favored them.

President Cleveland had supported Spain keeping control of Cuba. He worried that an independent Cuba might lead to racial conflict or intervention by another European country. McKinley also wanted a peaceful solution. He hoped to convince Spain to give Cuba independence or at least some self-rule. Negotiations began in 1897, but Spain would not give Cuba independence. The Cuban rebels and their American supporters would not accept anything less.

Most businesses strongly supported McKinley's slow approach. They were against war because they feared it would hurt the economy. However, many church leaders and activists wrote letters to politicians, demanding action in Cuba. These leaders then pressured McKinley to let Congress decide on war.

In January 1898, Spain offered some changes to its rule. But when riots broke out in Havana, McKinley sent the battleship USS Maine to show American concern. On February 15, the Maine exploded and sank, killing 266 sailors. Many Americans were angry at Spain. McKinley insisted on an investigation to find out if the explosion was an accident. On March 20, the investigation found that an underwater mine had blown up the Maine.

As pressure for war grew in Congress, McKinley kept trying to negotiate for Cuban independence. Spain refused his offers. On April 11, McKinley turned the matter over to Congress. He did not ask for war directly, but Congress declared war on April 20. They added the Teller Amendment, which said the U.S. had no intention of taking over Cuba. European countries urged Spain to negotiate, but Spain chose to fight alone to defend its honor.

How the War Was Fought

McKinley used new technologies like the telegraph and telephone to control the war. He set up the first "war room" to direct the Army and Navy. McKinley expanded the U.S. Army from 25,000 to 61,000 soldiers. Including volunteers, 278,000 men served in the Army during the war. McKinley wanted to unite the country. White Southerners eagerly supported the war, and a former Confederate general was given a senior command.

The Navy had planned to attack the Philippines if war broke out. On April 24, McKinley ordered Commodore George Dewey to attack the Philippines. On May 1, Dewey's fleet defeated the Spanish navy at the Battle of Manila Bay. This destroyed Spain's naval power in the Pacific. McKinley then sent more troops to the Philippines. He decided that Spain would have to give the islands to the U.S. He worried that Japan or Germany might take the islands if the U.S. did not.

Meanwhile, in the Caribbean, a large force gathered in Florida to invade Cuba. The Army had trouble supplying its rapidly growing force. The U.S. Navy began blocking Cuba in April. Spain had about 80,000 soldiers on the island. Disease was a big problem for American soldiers. For every soldier killed in combat, seven died of disease.

The main combat army sailed from Florida on June 20. They landed near Santiago de Cuba two days later. After a small fight, the American army fought Spanish forces on July 2 in the Battle of San Juan Hill. The Americans won this intense, day-long battle. Both sides had many casualties. Theodore Roosevelt, who had left his Navy job, led the "Rough Riders" into battle. His actions helped him become governor of New York later that year.

After the American victory, the Spanish fleet in Santiago's harbor tried to escape. But the U.S. Navy destroyed them in the Battle of Santiago de Cuba. This was the largest naval battle of the war. The U.S. then surrounded Santiago, and the city surrendered on July 17. This put Cuba under American control. McKinley also ordered an invasion of Puerto Rico, which met little resistance. Spain, with its navy destroyed, looked for a way to end the war.

The Peace Treaty

On July 22, Spain asked France to represent it in peace talks with the U.S. Spain first wanted to only give up Cuba. But they soon realized they would lose other lands as well. McKinley's cabinet agreed that Spain must leave Cuba and Puerto Rico. However, they disagreed about the Philippines. Some wanted to take the whole group of islands, while others only wanted a naval base.

Most Americans supported taking over the Philippines. But some important Democrats and other leaders were against it. These opponents formed the American Anti-Imperialist League. McKinley finally decided he had to annex the Philippines. He believed Japan would take them if the U.S. did not.

McKinley proposed peace talks based on Cuba's freedom and Puerto Rico's annexation. The future of the Philippines would be discussed later. Spain agreed to a ceasefire on these terms on August 12. Treaty talks began in Paris in September 1898 and lasted until December 18. The Treaty of Paris was signed on that day. The United States gained Puerto Rico, the Philippines, and Guam. Spain gave up its claims to Cuba. In return, the U.S. agreed to pay Spain $20 million.

McKinley had to work hard to get the Senate to approve the treaty. But with his and Vice President Hobart's help, the Senate voted to ratify it on February 6, 1899.

After the Spanish–American War

The Philippines

McKinley did not recognize the Filipino government led by Emilio Aguinaldo. Relations between the U.S. and Aguinaldo's supporters got worse after the Spanish–American War. McKinley believed that Aguinaldo only represented a small part of the Filipino people. He thought that fair American rule would lead to peace.

In February 1899, Filipino and American forces clashed. This started the Philippine–American War. The fighting in the Philippines led to more criticism from the anti-imperialist movement in the U.S. U.S. forces defeated the main Filipino army, but Aguinaldo began using guerrilla tactics. McKinley sent a group led by William Howard Taft to set up a civilian government. McKinley later made Taft the civilian governor of the Philippines. The Filipino rebellion mostly ended when Aguinaldo was captured in March 1901.

Roosevelt continued McKinley's policies. These included removing Catholic friars, improving roads and buildings, starting public health programs, and modernizing the economy. Roosevelt eventually saw the islands as a weakness. He told Taft in 1907 that he would be happy to see the islands become independent. By then, the U.S. was focusing more on Latin America. Roosevelt began preparing the Philippines to become the first Western colony in Asia to govern itself.

Cuba

Cuba was badly damaged by the war and the long fight against Spain. McKinley refused to recognize the Cuban rebels as the official government. However, he felt bound by the Teller Amendment, which promised Cuba independence. He set up a military government on the island. Many Republican leaders hoped that American leadership would eventually convince Cubans to ask to be annexed by the U.S. Even if not annexed, McKinley wanted a stable Cuban government that could resist European interference and remain friendly to the U.S.

With McKinley's help, Congress passed the Platt Amendment. This set conditions for the U.S. to leave Cuba. The conditions allowed the U.S. to have a strong role in Cuba, despite the promise of independence. Cuba gained independence in 1902. But it became a country that the U.S. protected. Roosevelt approved a trade agreement with Cuba in 1902, which lowered tariffs between the two countries.

In 1906, a rebellion broke out against Cuban President Tomás Estrada Palma. Both sides asked the U.S. to intervene. Roosevelt was hesitant. When Estrada Palma resigned, Secretary of War Taft declared that the U.S. would intervene under the Platt Amendment. This began the Second Occupation of Cuba. U.S. forces restored peace, and the occupation ended before Roosevelt left office.

Puerto Rico

After Puerto Rico was hit by a huge hurricane in 1899, Secretary of War Root suggested removing all tariffs (taxes) on goods from Puerto Rico. This caused a disagreement between McKinley's government and Republican leaders in Congress. They were worried about lowering the tariffs on newly acquired territories. McKinley reached a compromise. He signed a bill that cut tariffs on Puerto Rican goods to a small fraction of the usual rates.

Congress also passed the Foraker Act in 1900, which set up a civilian government for Puerto Rico. McKinley signed it into law on April 12, 1900. Under this law, all money collected from tariffs on Puerto Rican goods would go to Puerto Rico. The tariffs would stop once Puerto Rico set up its own tax system. In 1901, the Supreme Court supported McKinley's policies in the new territories, including Puerto Rico.

Puerto Rico became an important strategic location for the U.S. because of its position in the Caribbean Sea. It provided a good naval base for defending the Panama Canal. It also served as a link to the rest of Latin America. The U.S. created a new political status for the island. The Foraker Act made Puerto Rico the first unincorporated territory. This meant that the U.S. Constitution would not fully apply there. The U.S. invested in Puerto Rico's infrastructure and education system. However, many Puerto Ricans still wanted independence and continued to speak Spanish.

Roosevelt as President

Winning the Spanish–American War made the U.S. a power in both the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. McKinley won the 1900 election by a landslide, largely because of his foreign policy success. After McKinley's death in 1901, Roosevelt promised to continue his policies and increase American influence worldwide.

Roosevelt believed the U.S. had a duty to maintain a balance of power among nations and reduce tensions. He was also firm about upholding the Monroe Doctrine, which opposed European colonization in the Western Hemisphere. Roosevelt saw Germany as the biggest potential threat. He feared Germany might try to set up a base in the Caribbean. Because of this, Roosevelt sought closer ties with Britain, Germany's rival.

Roosevelt also wanted to expand U.S. influence in East Asia and the Pacific. In these regions, Japan and the Russian Empire had a lot of power.

Roosevelt focused on expanding and improving the U.S. military. In 1890, the United States Army had only 39,000 men, making it the smallest army of any major power. The Spanish–American War showed that the Army needed better control and planning. Roosevelt strongly supported reforms proposed by Secretary of War Elihu Root. Root helped enlarge West Point and established the U.S. Army War College. He also improved promotion procedures and training for officers.

Roosevelt made naval expansion a top priority. During his time in office, the Navy gained more ships, officers, and sailors. By 1904, the U.S. had the fifth largest navy in the world, and by 1907, it had the third largest. Roosevelt sent the "Great White Fleet" on a world tour in 1908–1909. This showed other naval powers that the U.S. was now a major player. While the U.S. fleet wasn't as strong as Britain's, it became the most powerful naval force in the Western Hemisphere.

Better Relations with Great Britain

The "Great Rapprochement" (a period of friendly relations) began with American support for Britain in the Boer War. It continued as Britain supported the U.S. during the Spanish–American War. Britain also pulled its fleet from the Caribbean to focus on the growing German naval threat. Roosevelt wanted to continue close ties with Britain. This would ensure peaceful, shared control over the Western Hemisphere.

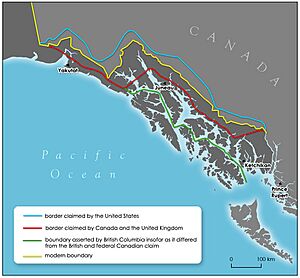

Britain accepted the Monroe Doctrine, and the U.S. accepted British control of Canada. Only two major issues remained between the U.S. and Britain: the Alaska boundary dispute and building a canal across Central America. Under McKinley, Secretary of State Hay had negotiated a treaty. In it, Britain agreed to the U.S. building the canal. Roosevelt got the Senate to approve this treaty in December 1901.

The border between Alaska and Canada became an issue in the late 1890s because of the Klondike Gold Rush. American and Canadian gold miners rushed to make claims. Access to the main Canadian gold fields required passing through Alaska. Canada wanted its own route. The U.S. argued that an 1825 treaty gave Alaska control over the disputed coastline.

A crisis in Venezuela briefly interrupted talks about the border. But Britain's actions ended the crisis and reduced the risk of conflict over Alaska. In January 1903, the U.S. and Britain agreed to let a six-member group decide the border. Roosevelt got the Senate to agree to this treaty in February 1903. The group had three American delegates, two Canadian delegates, and one British delegate. The British delegate sided with the Americans on most claims. The decision was announced in October 1903. This outcome strengthened relations between the U.S. and Britain. However, many Canadians were angry that Britain seemed to betray their interests.

Venezuela and the Roosevelt Corollary

In December 1902, Britain and Germany started blocking Venezuela. This was because Venezuela owed money to European countries. Both powers told the U.S. they didn't want to conquer Venezuela. Roosevelt sympathized with the European countries. But he suspected Germany might try to take Venezuelan land. Roosevelt and Hay worried that even a temporary occupation could lead to a permanent German military presence in the Western Hemisphere.

As the blockade began, Roosevelt sent the U.S. fleet under Admiral George Dewey. Roosevelt threatened to destroy the German fleet unless Germany agreed to let someone else decide the Venezuelan debt issue. Germany chose to let someone else decide rather than go to war. Through American help, Venezuela reached an agreement with Germany and Britain in February 1903.

Roosevelt would not allow European countries to take land in Latin America. But he also believed that Latin American countries should pay their debts to European countries. In late 1904, Roosevelt announced his Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine. It said that the U.S. would intervene in the finances of unstable Caribbean and Central American countries if they didn't pay their debts. This would prevent European powers from needing to intervene themselves. Roosevelt's statement was a warning to Germany. It helped keep peace in the region, as Germany decided not to intervene directly in Venezuela or other countries.

A crisis in the Dominican Republic became the first test for the Roosevelt Corollary. The country was deeply in debt and struggling to repay European lenders. Fearing another intervention by Germany and Britain, Roosevelt made an agreement with the Dominican president. The U.S. would take temporary control of the Dominican economy. The U.S. took control of the Dominican customs house. It brought in experts to fix the economy. This ensured money flowed to the Dominican Republic's foreign creditors. This intervention stabilized the country. The U.S. role there became a model for Taft's dollar diplomacy later on.

The Panama Canal

Under McKinley, Secretary of State Hay talked with Britain about building a canal across Central America. An earlier treaty from 1850 said neither country could control a canal alone. The Spanish–American War showed how hard it was to have a navy in both the Atlantic and Pacific oceans without a shorter connection than sailing around South America. With American business and military interests growing in Asia, a canal seemed more important than ever. McKinley pushed to change the treaty.

Britain, busy with the Second Boer War, agreed to a new treaty. Hay and the British ambassador agreed that the U.S. could control a future canal. It would be open to all ships and not fortified. McKinley was happy with this. But the Senate rejected it. They demanded that the U.S. be allowed to fortify the canal. Hay was embarrassed and offered to resign, but McKinley told him to keep negotiating. Hay succeeded, and a new treaty was approved just before McKinley's assassination in 1901.

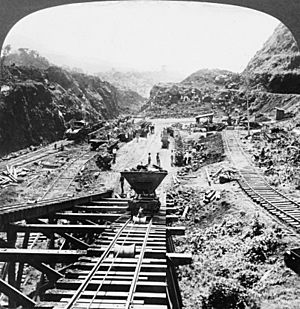

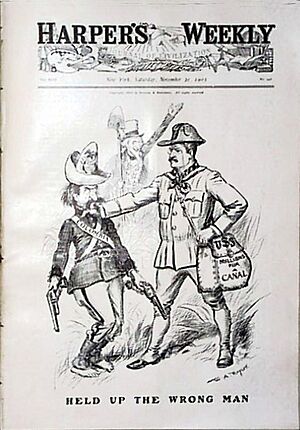

Roosevelt wanted to build a canal through Central America to connect the Atlantic Ocean and the Pacific Ocean. Most members of Congress preferred a canal through Nicaragua. But Roosevelt preferred the isthmus of Panama, which was loosely controlled by Colombia. A previous attempt to build a canal in Panama had failed. A commission had suggested Nicaragua but noted Panama might be cheaper and faster. Roosevelt and his advisors favored Panama. They believed a war with a European power might break out soon, and the U.S. fleet would be split until the canal was done.

After much debate, Congress passed a law in 1902. It gave Roosevelt $170 million to build the Panama Canal. Roosevelt's government then began talks with Colombia about building the canal through Panama.

The U.S. and Colombia signed a treaty in January 1903. It gave the U.S. a lease across the Isthmus of Panama. But the Colombian Senate refused to approve the treaty. They wanted more money from the U.S. and more control over the canal zone. Panamanian rebel leaders, who wanted to break away from Colombia, asked the U.S. for military help. Roosevelt saw Colombia's leader as corrupt. He believed Colombia had acted unfairly by rejecting the treaty.

When a rebellion started in Panama, Roosevelt sent the USS Nashville to stop the Colombian government from sending soldiers to Panama. Colombia could not regain control. Soon after Panama declared its independence in November 1903, the U.S. recognized Panama as an independent nation. Then, talks began about building the canal.

Secretary of State Hay and a French diplomat representing Panama quickly negotiated a new treaty. Signed on November 18, 1903, it created the Panama Canal Zone. The U.S. would control this zone and build the canal. Panama sold the Canal Zone to the U.S. for $10 million and a growing yearly payment. In February 1904, Roosevelt got the Senate to approve the treaty.

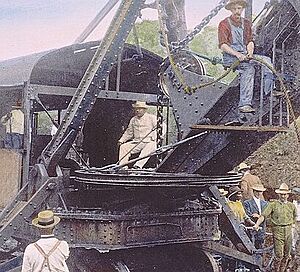

A commission was set up to govern the zone and oversee canal construction. Roosevelt visited Panama in November 1906 to check on progress. He was the first sitting president to travel outside the U.S. The canal was completed in 1914.

Solving Disputes Peacefully

A big moment for America's role in Europe was the Moroccan crisis of 1905–1906. France and Britain had agreed that France would control Morocco. But Germany suddenly protested. Germany asked Roosevelt to help settle the issue. He helped arrange a meeting in Algeciras, Morocco, where the crisis was solved. Roosevelt told Europeans that the U.S. would probably avoid getting involved in Europe in the future.

Russo-Japanese War

Russia had taken over the Chinese region of Manchuria after the 1900 Boxer Rebellion. The U.S., Japan, and Britain all wanted Russia to leave. Russia agreed to withdraw in 1902, but then broke its promise. Japan prepared for war against Russia to remove it from Manchuria. When the Russo-Japanese War began in February 1904, Roosevelt sided with Japan. But he wanted to be a mediator in the conflict. He hoped to keep the Open Door policy in China and prevent either country from becoming too powerful in East Asia.

Both Japan and Russia expected to win the war at first. But Japan gained a big advantage after capturing a Russian naval base in January 1905. In mid-1905, Roosevelt convinced both sides to meet for peace talks in New Hampshire. His efforts led to the signing of the Treaty of Portsmouth on September 5, ending the war. Roosevelt won the 1906 Nobel Peace Prize for his work. The treaty removed Russian troops from Manchuria. It also gave Japan control of Korea and the southern half of Sakhalin Island.

Jewish Persecution in Russia

Many large, violent attacks against Jewish people in Russia (called pogroms) in the late 1800s and early 1900s angered Americans. Jewish leaders in the U.S. organized protests and met with President Roosevelt and Secretary John Hay. They asked the Russian Tsar to stop the persecution. Roosevelt publicly spoke out against the attacks. However, because he was mediating the war between Russia and Japan, he couldn't openly take sides. Secretary Hay took the lead in Washington. Roosevelt eventually sent a petition to the Tsar, who blamed the Jewish people.

The attacks continued, and hundreds of thousands of Jewish people fled Russia, mostly to London or New York. American public opinion turned against Russia. In 1906, Congress officially condemned Russia's policies. Roosevelt appointed the first Jewish person to his cabinet, Oscar Straus, as Secretary of Commerce and Labor.

Algeciras Conference

In 1906, at Germany's request, Roosevelt convinced France to attend the Algeciras Conference. This was to solve the First Moroccan Crisis. France had tried to control Morocco, and Germany protested. Germany's Kaiser wanted to test the new alliance between Britain and France. He also hoped to draw the U.S. into an alliance against them.

Some U.S. senators protested American involvement in European affairs. But Secretary of State Root helped defeat their efforts. The conference was held in Spain, with 13 nations attending. The main issue was who would control the police in Moroccan cities. Germany found itself in the minority. Roosevelt secretly supported France. An agreement was reached on April 7, 1906. It slightly reduced French influence by confirming Morocco's independence. Germany gained nothing important but stopped threatening war.

Taft's Policies

Taft did not like the old practice of giving important ambassador jobs to wealthy supporters. He preferred diplomats who were not too lavish. Taft tried to settle international disputes through arbitration (having a third party make a decision). In 1911, Taft and his Secretary of State, Philander C. Knox, negotiated treaties with Britain and France. These treaties said that disagreements should be settled by a court or other group.

However, Taft and Knox did not talk to senators while negotiating these treaties. Many Republicans were against Taft at the time. The Senate added changes to the treaties that Taft could not accept, which killed the agreements.

This issue showed a disagreement among progressives. Many progressives believed that legal arbitration was a better way to solve problems than war. Taft, who later became Chief Justice, understood the legal side well. His supporters, mainly conservative business people, also wanted peace. They believed that trade would make countries dependent on each other, making war too costly.

One success was settling a fishing dispute between the U.S. and Britain in 1910. But Taft's 1911 treaties with France and Britain were stopped by Roosevelt. Roosevelt had fallen out with Taft and was trying to gain control of the Republican Party. Roosevelt worked with Senator Henry Cabot Lodge to add the changes that ruined the treaties. Roosevelt truly believed that big issues had to be decided by war, not just arbitration.

Even though no general arbitration treaty was signed, Taft's government settled several disputes with Britain peacefully. These included the border between Maine and New Brunswick, and disagreements over seal hunting and fishing rights.

Canada Rejects Trade Treaty

Anti-American feelings were very strong in Canada in 1911. Taft hoped to gain support with a trade treaty with Canada. This treaty would lower tariffs and remove many trade barriers. The Canadian government agreed to negotiate.

However, Canadian manufacturers worried that free trade would let larger American factories take over their markets. Conservatives in Canada opposed the agreement. They feared it would lead to more American influence and pull Canada away from Britain.

American farmers and paper mills also objected because they would lose tariff protection. Still, Taft reached an agreement with Canada in early 1911, and Congress approved it in July 1911. But the Canadian Parliament was divided. Canada then called an election in 1911. The election focused on economic fears and Canadian nationalism. The Conservative party warned that the treaty would be a "sell out" to the U.S. Their slogan was "No truck or trade with the Yankees." They won a big victory. The treaty was dead, and this unexpected loss further hurt Taft's reputation.

Dollar Diplomacy in Action

Taft and Secretary of State Knox used "Dollar Diplomacy" in Latin America. They believed U.S. investments would help everyone and reduce European influence. However, this policy was not popular among Latin American countries. They didn't want to become financially controlled by the U.S. Dollar Diplomacy also faced opposition in the U.S. Senate. Many senators thought the U.S. should not interfere abroad.

In Nicaragua, American diplomats quietly supported rebel forces against the government. The country owed money to several foreign powers. The U.S. didn't want it to fall under European control. The government could not stop the rebellion. In 1910, the rebels took the capital. The U.S. had Nicaragua accept a loan and sent officials to make sure it was repaid. The country remained unstable. After more problems, Taft sent troops in 1912. Some troops stayed until 1933.

The Mexican Revolution

No foreign issue challenged Taft more than the collapse of the Mexican government and the chaos of the Mexican Revolution. When Taft took office, Mexico was restless under the long rule of Porfirio Díaz. Díaz faced strong opposition from Francisco I. Madero and social unrest from Emiliano Zapata and Pancho Villa.

In October 1909, Taft and Díaz met at the U.S.-Mexico border. These were the first meetings between a U.S. and a Mexican president. Díaz hoped to show that his government had U.S. support. Taft mainly wanted to protect American businesses in Mexico. These meetings helped start the building of the Elephant Butte Dam in 1911.

The situation in Mexico got worse in 1910. Mexican rebels crossed the U.S. border to get weapons. After Díaz jailed Madero before the 1910 election, Madero's supporters fought against the government. This led to Díaz being removed from power and a revolution that lasted ten years. Taft sent 20,000 American troops to the Mexican border in March 1911. This was to protect American citizens and businesses in Mexico. He said he would not be easily drawn into a fight.

Relations with Japan (1897–1913)

Hawaii

The U.S. took over Hawaii in 1898 partly because it feared Japan might take it instead. Similarly, Japan was seen as an alternative to American control of the Philippines in 1900. These events were part of the U.S. becoming a naval world power. But it needed to find a way to avoid military conflict with Japan in the Pacific. Theodore Roosevelt made it a high priority to keep friendly relations with Japan.

Korea's Status

Roosevelt saw Japan as the rising power in Asia. He viewed Korea as a less developed nation. He did not object to Japan trying to control Korea. The U.S. signaled it would not intervene militarily to stop Japan's takeover of Korea. In mid-1905, Taft and Japanese Prime Minister Katsura Tarō made an agreement. Japan said it had no interest in the Philippines. The U.S. said it considered Korea to be under Japan's influence.

Anti-Japanese Feelings

Strong anti-Japanese feelings among Americans on the West Coast hurt relations during the latter part of Roosevelt's time in office. In 1906, the San Francisco Board of Education caused a diplomatic problem. They ordered all Japanese schoolchildren in the city to be separated from others. The Roosevelt administration did not want to anger Japan by stopping Japanese immigration, as they had done for Chinese immigration.

Instead, the two countries reached an informal agreement in 1907, called the Gentlemen's Agreement of 1907. Japan agreed to stop Japanese laborers from moving to the U.S. and Hawaii. In return, the San Francisco School Board's segregation order was canceled. This agreement lasted until 1924, when Congress completely stopped immigration from Japan. Despite the agreement, tensions with Japan continued because of how Japanese immigrants were treated by local governments. Roosevelt never feared war with Japan, but the friction encouraged more naval build-up and a focus on U.S. security in the Pacific.

Taft continued Roosevelt's policies on immigration from China and Japan. A new treaty between the U.S. and Japan in 1911 gave broad rights to Japanese people in America and Americans in Japan. But it was based on the 1907 Gentlemen's Agreement continuing. There were objections on the West Coast when the treaty was sent to the Senate. But Taft told politicians that immigration policy would not change.

Relations with China (1897–1913)

Secretary of State John Hay handled China policy until 1904. After the war between Russia and Japan broke out, Roosevelt took over. Both started with big plans for American involvement in Asia. But within a year, they pulled back. They realized the American public did not want deeper involvement. So their efforts to find a naval port, build railroads, or increase trade did not succeed.

Even before peace talks with Spain, Hay asked Congress to study trade opportunities in Asia. He supported an "Open Door Policy". This policy meant all nations could trade freely with China, and no one would try to take over Chinese land. Hay sent notes about the Open Door to European powers. Britain liked the idea, but Russia opposed it. France, Germany, Italy, and Japan said they agreed in principle, but only if all other nations agreed. Hay then announced that the policy had been accepted by everyone. Every power promised to uphold the Open Door.

Boxer Rebellion (1900)

American missionaries were threatened, and trade with China was in danger during the Boxer Rebellion in 1900. Foreigners and their property in China were attacked. Americans and other Westerners in Peking were surrounded. In cooperation with seven other powers, McKinley sent 5,000 troops to the city in June 1900. The rescue went well. Some members of Congress objected to McKinley sending troops without asking Congress first. But McKinley's actions set a pattern for future presidents to use their own control over the military. After the rebellion ended, the U.S. again promised to support the Open Door policy. It used the money China paid as reparations to bring Chinese students to American schools.

Chinese Boycott (1905)

Because of strict limits on Chinese immigration to the U.S., Chinese people living overseas organized a boycott. People in China refused to buy American products. This boycott was organized by a reform group. It had only a small economic impact because China bought few American products other than kerosene. Washington was angry and treated the boycott like a violent attack. It demanded that the Chinese government stop it. President Theodore Roosevelt asked Congress for money for a naval expedition. Washington refused to ease the immigration laws. This was because of strong anti-Chinese feelings, especially on the West Coast. The U.S. began to speak out against Chinese nationalism. The boycott had a big impact on Chinese people worldwide. It marked the beginning of modern nationalism in China.

President Taft and China

Having been governor of the Philippines, Taft was very interested in Asian affairs. He thought the position of minister to China was the most important in the Foreign Service. Taft and Knox tried to extend John Hay's Open Door Policy to Manchuria, but without success.

In 1909, a British-led group began talks to loan money for a railroad in China. Taft tried for years to get American banks to join this project. But Britain and then China blocked his efforts. Finally, in 1911, Western powers forced China to approve the project. Widespread opposition across China to this Western influence helped start the Chinese Revolution of 1911.

Revolution of 1911

After the Chinese Revolution began in 1911, the leaders chose Sun Yat-sen as the temporary president of what became the Republic of China. This overthrew the Manchu Dynasty. Taft was slow to recognize the new government, even though American public opinion supported it. The U.S. House of Representatives passed a resolution supporting a Chinese republic in February 1912. But Taft and Knox felt that recognition should come from all Western powers together. In his last message to Congress in December 1912, Taft said he was moving toward recognition once the republic was fully established. But he had already lost his bid for re-election and did not follow through.

Relations with France

The removal of Napoleon III in 1870 helped improve relations between France and the U.S. During the German siege of Paris, the small American community in the city provided medical and humanitarian help. This earned Americans much respect. In later years, the U.S. grew much faster in wealth and industry. This made it more powerful than the older European nations. Trade between the U.S. and France was low, and there were high tariffs.

Throughout this period, the relationship remained friendly. The Statue of Liberty, given as a gift from the French people in 1884, symbolized this friendship. From 1870 until 1918, France was the only major republic in Europe, which made it special to the U.S. Many French people admired the U.S. as a land of opportunity and modern ideas. However, few French people moved to the U.S. Some French thinkers saw the U.S. as a place focused only on money, without much culture.

As the U.S. grew stronger economically and formed closer ties with Britain, the French increasingly worried about an "Anglo-Saxon" (British and American) threat to their culture.

Images for kids

-

President Theodore Roosevelt personally guided U.S. foreign policy from 1901 to 1909.

-

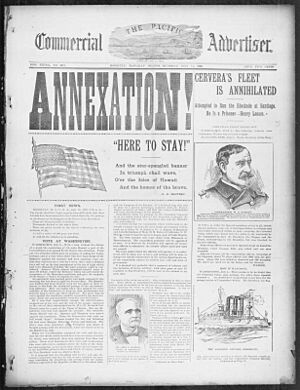

Annexation of the Republic of Hawaii in 1898.

-

Signing of the Treaty of Paris.

-

American soldiers scale the walls of Beijing to help civilians trapped by Boxers, August 1900.

-

Taft and Porfirio Díaz, Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, 1909.

-

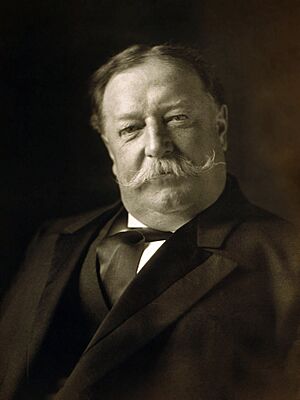

William Taft in 1909.

-

Construction of the Statue of Liberty in Paris.

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |