Liliʻuokalani facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Liliʻuokalani |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||

| Queen of the Hawaiian Islands (more...) | |||||

| Reign | January 29, 1891 – January 17, 1893 | ||||

| Predecessor | Kalākaua | ||||

| Successor | Monarchy overthrown | ||||

| Born | September 2, 1838 Honolulu, Oʻahu, Hawaiian Kingdom |

||||

| Died | November 11, 1917 (aged 79) Honolulu, Oʻahu, Territory of Hawaii |

||||

| Burial | November 18, 1917 Mauna ʻAla Royal Mausoleum |

||||

| Spouse |

John Owen Dominis

(m. 1862; died 1891) |

||||

|

|||||

| House | Kalākaua | ||||

| Father | Caesar Kapaʻakea. Hānai adoptive father; Abner Pākī | ||||

| Mother | Analea Keohokālole. Hānai adoptive mother; Laura Kōnia | ||||

| Religion | Protestantism (more...) | ||||

| Signature | |||||

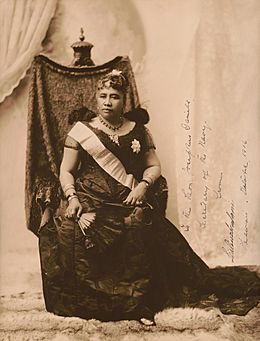

Liliʻuokalani (born Lydia Liliʻu Loloku Walania Kamakaʻeha; September 2, 1838 – November 11, 1917) was the only queen and the last ruler of the Hawaiian Kingdom. She ruled from January 29, 1891, until the Hawaiian monarchy was overthrown on January 17, 1893. She is famous for composing the song "Aloha ʻOe" and many other musical works. While she was held captive after the overthrow, she wrote her life story, called Hawaiʻi's Story by Hawaiʻi's Queen.

Liliʻuokalani was born in Honolulu, Oʻahu, on September 2, 1838. Her birth parents were Analea Keohokālole and Caesar Kapaʻakea. However, she was adopted at birth by Abner Pākī and Laura Kōnia through a Hawaiian custom called hānai. She grew up with their daughter, Bernice Pauahi Bishop. Liliʻuokalani was baptized as a Christian and went to the Royal School. She and her relatives were later declared eligible to rule by King Kamehameha III.

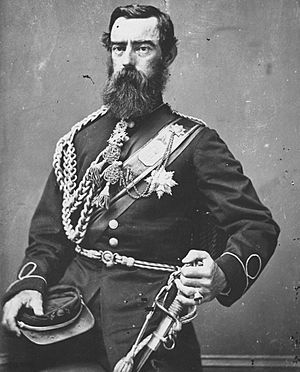

She married John Owen Dominis, who was born in America. He later became the Governor of Oʻahu. They did not have their own biological children but adopted several. After her brother David Kalākaua became king in 1874, Liliʻuokalani and her siblings were given royal titles like Prince and Princess. In 1877, after her younger brother Leleiohoku II passed away, she was named the next in line to the throne. She even represented her brother in the United Kingdom during Queen Victoria's Golden Jubilee.

Contents

Becoming Queen of Hawaii

Liliʻuokalani became queen on January 29, 1891, just nine days after her brother King Kalākaua died. During her time as queen, she tried to create a new constitution. This new constitution would have given more power back to the monarchy and restored voting rights to many Native Hawaiians and Asians who had lost them.

However, powerful American business owners in Hawaiʻi felt threatened by her efforts. They wanted to keep the power they had gained under the Bayonet Constitution. These groups overthrew the monarchy on January 17, 1893. The overthrow was helped by US Marines, who landed to protect American business interests. This made it impossible for the Hawaiian monarchy to defend itself.

Life After the Monarchy

After the overthrow, a new government called the Republic of Hawaiʻi was formed. Their main goal was to have the islands become part of the United States. However, US President Grover Cleveland temporarily stopped this plan.

Later, there was an unsuccessful attempt to bring back the monarchy. After this, the new government placed Liliʻuokalani under house arrest at the ʻIolani Palace. On January 24, 1895, Liliʻuokalani was forced to give up her claim to the Hawaiian throne. This officially ended the monarchy.

People continued to try and restore the monarchy and oppose annexation. But when the Spanish–American War began, the United States officially took over Hawaiʻi through the Newlands Resolution. Liliʻuokalani lived the rest of her life as a private citizen. She died at her home, Washington Place, in Honolulu on November 11, 1917.

Her Early Life and Family

Liliʻuokalani was born Lydia Liliʻu Loloku Walania Kamakaʻeha on September 2, 1838. She was born in a large grass hut in Honolulu, Oʻahu. According to Hawaiian custom, she was named after an event around her birth. At that time, the regent, Elizabeth Kīnaʻu, had an eye infection. So, the child was named with words meaning "smarting," "tearful," "burning pain," and "sore eyes." She was later baptized and given the Christian name Lydia.

Her family belonged to the aliʻi class, which was the Hawaiian nobility. They were related to the ruling House of Kamehameha. Her family line was very important in Hawaiian history. Liliʻuokalani was the third child to survive in her large family. Her biological siblings included James Kaliokalani, David Kalākaua, Anna Kaʻiulani, Miriam Likelike, and William Pitt Leleiohoku II.

As was the custom, she and her siblings were hānai (informally adopted) to other family members. Liliʻuokalani was given to Abner Pākī and his wife Laura Kōnia. She grew up with their daughter, Bernice Pauahi.

School Days

In 1842, at age four, Liliʻuokalani started school at the Chiefs' Children's School, also known as the Royal School. King Kamehameha III had officially declared that she and her classmates were eligible for the Hawaiian throne. Liliʻuokalani later wrote that these students were "exclusively persons whose claims to the throne were acknowledged."

She and her two older brothers, James and David, along with thirteen royal cousins, were taught in English by American missionaries. They learned subjects like reading, math, history, music, and English writing. Liliʻuokalani was among the youngest students. She later remembered her early education as difficult at times. In 1848, a measles outbreak took the lives of a classmate and her younger sister.

After the boarding school closed around 1850, she continued her education at a day school. In 1865, after she was married, she also attended Oʻahu College (now Punahou School) for a short time.

Her Marriage and Royal Duties

After school, Liliʻuokalani lived with her adoptive parents at Haleʻākala. Her adoptive sister, Pauahi, married Charles Reed Bishop. Liliʻuokalani became part of the young social group during the reign of Kamehameha IV. She was a close friend of Queen Emma and served as a maid of honor at the royal wedding. She also attended official state events as a lady-in-waiting for Queen Emma.

Liliʻuokalani was briefly engaged to William Charles Lunalilo, who later became king. They both loved music. However, she ended the engagement because King Kamehameha IV and the Bishops did not approve.

Afterward, she became close with John Owen Dominis, who was born in America. He worked for Prince Lot Kapuāiwa (who would become Kamehameha V). They had known each other since childhood.

Liliʻuokalani and Dominis were engaged from 1860 to 1862. They married on September 16, 1862, at Haleʻākala. The ceremony was led by Reverend Samuel C. Damon. The royal family attended the wedding. The couple moved into Dominis' home, Washington Place in Honolulu. John Owen Dominis later became Governor of Oʻahu and Maui. They did not have biological children, but Liliʻuokalani adopted three hānai children: Lydia Kaʻonohiponiponiokalani Aholo, Joseph Kaiponohea ʻAeʻa, and John ʻAimoku Dominis (her husband's son).

Liliʻuokalani remained active in the royal court. She helped Queen Emma and King Kamehameha IV raise money to build The Queen's Hospital. In 1864, she helped establish the Kaʻahumanu Society, a women's group that helped the elderly and sick. At the request of King Kamehameha V, she wrote "He Mele Lāhui Hawaiʻi" in 1866, which became the Hawaiian national anthem for a time.

Becoming Heir to the Throne

When King Kamehameha V died in 1872 without an heir, the Hawaiian constitution said the legislature would elect the next monarch. Lunalilo was chosen as the first elected king. But Lunalilo also died without an heir in 1874.

In the next election, Liliʻuokalani's brother, David Kalākaua, ran against Emma, the former queen. When Kalākaua was chosen, it caused a riot at the courthouse. US and British troops had to intervene.

After Kalākaua became king, he gave royal titles to his surviving siblings. His brother, William Pitt Leleiohoku, was named heir to the throne because Kalākaua and Queen Kapiʻolani had no children. However, Leleiohoku died in 1877. On April 10, Liliʻuokalani was officially named the new heir to the throne of Hawaii. It was at this time that King Kalākaua changed her name to Liliʻuokalani, meaning "the smarting of the royal ones."

Serving as Regent

When King Kalākaua went on a world tour in 1881, Liliʻuokalani served as Regent, meaning she ruled in his place. One of her first big challenges was dealing with a smallpox outbreak. She closed all ports, stopped passenger ships, and started a quarantine. These actions helped keep the disease from spreading widely.

During this time, Liliʻuokalani also visited the Kalaupapa Leper Settlement on Molokaʻi. She was deeply moved by what she saw. She later honored Father Damien for his service to the people there. She also helped set aside land for a leprosy hospital.

Liliʻuokalani cared deeply about her people. In 1886, she started a bank for women in Honolulu. She also founded the Liliʻuokalani Educational Society. This group helped pay for Hawaiian girls to attend schools like Kawaiahaʻo Seminary and Kamehameha Schools.

Trip to England and Political Changes

In April 1887, King Kalākaua sent a group to London for Queen Victoria's Golden Jubilee. This group included Queen Kapiʻolani, Princess Liliʻuokalani, and her husband. They traveled across the United States, visiting Washington, D.C., and New York City before sailing to the United Kingdom. In Washington, they met President Grover Cleveland.

In London, Queen Kapiʻolani and Liliʻuokalani had an official meeting with Queen Victoria at Buckingham Palace. They attended the Jubilee service at Westminster Abbey. Soon after the celebrations, they received shocking news: King Kalākaua had been forced to sign the Bayonet Constitution under threat. They quickly canceled their European tour and returned to Hawaii.

This new constitution greatly reduced the king's power. In 1889, a Native Hawaiian officer named Robert William Wilcox led an unsuccessful rebellion to try and get rid of the Bayonet Constitution.

King Kalākaua's Death

King Kalākaua's health was getting worse. In November 1890, he traveled to California. There was some uncertainty about why he went, but it was partly for his health. Liliʻuokalani was left in charge as regent for the second time.

Kalākaua stayed in San Francisco and traveled in California. He suffered a stroke and died on January 20, 1891. The news of his death reached Hawaii on January 29, when his ship returned to Honolulu with his remains.

Her Reign as Queen

On January 29, 1891, Liliʻuokalani took an oath to uphold the constitution. She became the first and only female monarch of the Hawaiian Kingdom. The first few weeks of her reign were focused on her brother's funeral.

After the mourning period, she asked the cabinet ministers from her brother's reign to resign. They refused, but the Hawaii Supreme Court ruled in favor of the Queen. So, the ministers resigned. Liliʻuokalani appointed new ministers. On March 9, she named her niece, Kaʻiulani, as her successor. Kaʻiulani was the only daughter of Liliʻuokalani's sister Princess Likelike.

Her husband, John Owen Dominis, was given the title of Prince Consort and became Governor of Oʻahu again. However, Dominis died on August 27, just seven months into her reign. This deeply affected the new Queen. She later wrote that his experience and popularity would have made him an invaluable advisor.

From May 1892 to January 1893, the Hawaiian legislature met for a very long time, 171 days. This session was full of political disagreements. People wanted a new constitution and a lottery bill. The main issues between the Queen and the lawmakers were about her cabinet ministers. The 1887 constitution allowed the legislature to dismiss her cabinet. Four of her chosen cabinets were removed by votes from the legislature.

On January 13, 1893, after the legislature dismissed her latest cabinet, Liliʻuokalani appointed a new one. She chose these men specifically to support her plan to create a new constitution while the legislature was not meeting.

Attempting a New Constitution

The main event that led to the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom in 1893 was Queen Liliʻuokalani's attempt to create a new constitution. She wanted to regain power for the monarchy and for Native Hawaiians, power that had been lost under the Bayonet Constitution.

Her opponents were very angry about her attempt to make a new constitution. They decided to remove the Queen, overthrow the monarchy, and try to make Hawaii part of the United States. These opponents were mostly American and European businessmen living in Hawaiʻi.

Soon after she became queen, Liliʻuokalani received many requests to rewrite the Bayonet Constitution. She had the support of two-thirds of the voters. She tried to get rid of the old constitution, but her cabinet ministers did not support her. They knew how her opponents would react.

The proposed constitution would have given more power back to the monarchy. It also would have restored voting rights to many Native Hawaiians and Asians who had lost them. Her ministers and close friends tried to stop her from doing this, but she went ahead. These actions were later used against her.

The Overthrow of the Monarchy

The political tension led to many rallies and meetings in Honolulu. Groups against the monarchy, who wanted Hawaii to be annexed by the US, formed the Committee of Safety. They planned to remove the Queen.

In response, supporters of the Queen formed the Committee of Law and Order. They met at the palace on January 16, 1893. Leaders spoke in support of the Queen. To try and calm things down, the Queen and her supporters stopped trying to create a new constitution on their own.

On the same day, the Marshal of the Kingdom, Charles Burnett Wilson, learned about the planned overthrow. He asked for warrants to arrest the 13 members of the Committee of Safety. He also wanted to put the Kingdom under martial law. But the Queen's cabinet ministers refused his requests. They feared that arrests would make the situation worse, especially since the Committee members had strong ties to the US Minister to Hawaii, John L. Stevens.

Wilson and the captain of the Royal Household Guard had gathered 496 men to protect the Queen. However, Marines from the USS Boston and US sailors landed. They took positions at the US Legation and Consulate. The US forces did not enter the palace or fire any shots. But their presence was enough to scare away the royalist defenders. This made it impossible for the monarchy to protect itself.

The Queen was removed from power on January 17. A new provisional government was set up, led by Sanford B. Dole. The US Minister Stevens quickly recognized this new government. Liliʻuokalani temporarily gave up her throne to the United States, not to Dole's government. She hoped that the US would restore Hawaii's independence to her.

The new government started using ʻIolani Palace as its main building. A group went to Washington D.C. on January 19 to ask for Hawaii to be annexed by the United States right away. The US flag was raised over the palace, and martial law was put in place.

President Grover Cleveland later sent James Henderson Blount to investigate the overthrow. The Blount Report concluded that the overthrow was illegal. It said that Stevens and the American troops had acted improperly. On November 16, Cleveland suggested that Liliʻuokalani be returned to the throne if she promised to forgive everyone involved. She initially said that Hawaiian law called for punishment for treason. This made her lose some support from the Cleveland administration.

Cleveland sent the issue to Congress. He stated that the new government was not truly a republic but an "oligarchy" (rule by a small group) without the people's consent. The Queen changed her mind about forgiveness. On December 18, the US demanded that the provisional government put her back on the throne, but they refused. Congress then conducted its own investigation, which found Stevens and others "not guilty." The provisional government then formed the Republic of Hawaii on July 4, 1894, with Dole as its president.

Arrest and Imprisonment

In January 1895, Robert W. Wilcox led another rebellion against the Republic to try and bring back the Queen. This rebellion failed. Many people involved, and other supporters of the monarchy, were arrested. Liliʻuokalani was also arrested and imprisoned in an upstairs bedroom at the palace on January 16. This happened after guns were found at her home, Washington Place.

While imprisoned, she gave up her throne. She did this in exchange for her jailed supporters being released and having their death sentences changed. She signed the abdication document on January 24.

She was tried by a military court in the palace throne room on February 8. She said she didn't know about the rebellion. She was sentenced to five years of hard labor and fined $5,000. On September 4, her sentence was changed to imprisonment in the palace, where she was cared for by her lady-in-waiting. While confined, she wrote songs, including "The Queen's Prayer."

On October 13, 1896, the Republic of Hawaii gave her a full pardon and restored her rights. She later wrote her memoir, Hawaii's Story by Hawaii's Queen, which was published in 1898.

Annexation of Hawaii

After her release, Liliʻuokalani spent time between Hawaii and Washington, D.C. She worked to get money back from the United States for the lands that were taken.

She attended the inauguration of US President William McKinley on March 4, 1897. On June 16, McKinley presented a new annexation treaty to the US Senate. This treaty did not include any money for Liliʻuokalani. She filed an official protest the next day.

The treaty failed to pass in the United States Senate. This was because Native Hawaiian groups collected over 21,000 signatures opposing it. These petitions showed that many Hawaiians were against annexation. However, Hawaii was still annexed through the Newlands Resolution, a special act of Congress, in July 1898. This happened shortly after the Spanish–American War began.

The annexation ceremony was held on August 12, 1898, at ʻIolani Palace. The flag of the Republic of Hawaii was lowered, and the flag of the United States was raised. Liliʻuokalani and her family refused to attend the event. Many Native Hawaiians also boycotted the ceremony.

Crown Lands

Before 1848, all land in Hawaii was owned by the monarchy. After a land division, some land was set aside for the monarchy. These became known as the Crown Lands of Hawaii. When Hawaii was annexed, the US government took these lands. Liliʻuokalani tried to get these lands back, saying they were taken without proper payment.

In 1900, the US Congress passed the Hawaiian Organic Act. This act created a government for the Territory of Hawaii. The territorial government took control of the Crown Lands. These lands are now known as "Ceded Lands" and are still a topic of discussion in Hawaii.

In 1909, Liliʻuokalani filed a lawsuit against the United States to get the Crown Lands back. However, the courts ruled against her. They said that the Crown Lands were not strictly the private property of the monarch.

Later Life and Legacy

Even though Liliʻuokalani was not successful in getting her lands back, in 1911, she was granted a lifetime pension of $1,250 a month by the Territory of Hawaii. This amount was much less than what she had asked for.

In April 1917, Liliʻuokalani raised the American flag at Washington Place. This was to honor Hawaiian sailors who had died when their ship was sunk by German submarines. Many saw this as her showing support for the United States.

By the summer of 1917, she was too weak to hold her annual birthday reception. In September, she officially joined the American Red Cross. After several months of declining health, Liliʻuokalani died at her home in Washington Place on November 11, 1917, at the age of seventy-nine.

Bells rang 79 times to mark her age. Her body was taken to Kawaiahaʻo Church for public viewing. Then, she had a state funeral in the throne room of Iolani Palace on November 18. A youth choir sang "Aloha ʻOe" as her coffin was moved to the Royal Mausoleum of Mauna ʻAla. Many people joined the procession, singing her famous song.

Religious Beliefs

Liliʻuokalani was taught by American Protestant missionaries from a young age. She became a very religious Christian. She regularly attended services at Kawaiahaʻo Church, where she played the organ and led the choir. She also had a special interest in the Liliʻuokalani Protestant Church, to which she donated a clock in 1892.

She believed that all religions should be treated equally. Throughout her life, she showed interest in different Christian faiths. In 1896, she became a member of St. Andrew's Cathedral, which was an Anglican church. During her imprisonment, the Bishop of St. Andrew's Cathedral supported her. She was baptized and confirmed by him in 1896.

She also showed respect for other religions. In 1901, she visited Utah and met with the Mormon president. She also attended a Buddha's Birthday celebration in 1901. Her presence helped Buddhism and Shinto gain acceptance in Hawaiian society.

Her Musical Compositions

Liliʻuokalani was a talented writer and songwriter. Her book Hawaiʻi's Story by Hawaiʻi's Queen shared her view of her country's history and the overthrow. She played the guitar, piano, organ, ʻukulele, and zither. She also sang alto.

Liliʻuokalani helped keep Hawaiian traditional poetry alive while adding Western musical styles. A collection of her works, The Queen's Songbook, was published in 1999. She used her music to express her feelings for her people and her country. For example, while under house arrest, she translated the Kumulipo, an ancient Hawaiian creation chant. She feared she might not leave the palace alive and wanted to make sure her people's history and culture would not be lost.

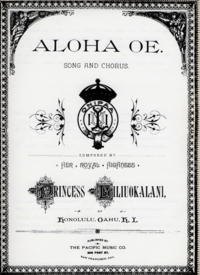

She continued to compose music even while imprisoned in ʻIolani Palace. One of her most famous songs, "Aloha ʻOe," was written earlier but transcribed during her confinement. She wrote that she found "great consolation in composing." Although originally a love song, "Aloha ʻOe" became a symbol of the loss of her country. Today, it is one of the most recognized Hawaiian songs.

Lasting Impact

Liliʻuokalani's friend, Julius A. Palmer Jr., said she showed "the most Christian forgiveness." Even newspapers that had supported the overthrow recognized her great respect around the world after her death. In 2016, Hawaiʻi Magazine named her one of the most influential women in Hawaiian history.

The Queen Liliʻuokalani Trust was created on December 2, 1909. Its purpose is to care for orphaned and needy children in Hawaii. After her death, most of her estate was used for this Trust. The Queen Liliʻuokalani Children's Center was later created by the Trust.

Liliʻuokalani and her siblings are honored by the Hawaiian Music Hall of Fame as Na Lani ʻEhā (The Heavenly Four). This is for their support and enrichment of Hawaii's musical culture. "Aloha ʻOe" was rated the greatest song in Hawaiian music history in 2007.

The annual Queen Liliʻuokalani Outrigger Canoe Race is held each year around her birthday, September 2. It is an 18-mile race for canoe teams.

In 2001, the "Queen Liliʻuokalani Center for Student Services" was named at the University of Hawaii at Manoa. The university noted that she "symbolizes an important link to traditional Hawaiian culture and society."

Many hula events are held to honor her memory, including the Queen Liliʻuokalani Keiki Hula Competition in Honolulu. The County of Hawaii also holds an annual festival at Liliʻuokalani Park and Gardens in Hilo to celebrate her birthday.

Titles and Symbols

Titles and Styles

- 1838 – September 16, 1862: The Honorable Miss Lydia Kamakaʻeha Pākī

- September 16, 1862 – 1874: The Honorable Mrs. Lydia Kamakaʻeha Dominis

- 1874 – April 10, 1877: Her Royal Highness The Princess Lydia Kamakaʻeha Dominis

- April 10, 1877 – January 29, 1891: Her Royal Highness The Princess Liliʻuokalani, Heir Apparent

- January 20, 1881 – October 29, 1881 and November 25, 1890 – January 29, 1891: Her Royal Highness The Princess Regent

- January 29, 1891 – January 17, 1893: Her Majesty The Queen

Royal Symbols

|

|

|

| Monogram of Queen Liliʻuokalani | Coat of arms of the Kalākaua Dynasty | Monogram of Queen Liliʻuokalani (variant) |

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Liliuokalani para niños

In Spanish: Liliuokalani para niños