Opposition to the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom facts for kids

The opposition to the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom refers to the many ways people fought against the Hawaiian monarchy being taken over. On January 17, 1893, the Hawaiian monarchy was overthrown. A new group, called the Provisional Government, led by Sanford B. Dole, tried to make Hawaii part of the United States.

However, the U.S. President at the time, Grover Cleveland, was a Democrat. He was against expanding U.S. territory and was a friend of the deposed Queen Liliʻuokalani. President Cleveland stopped the plan to annex Hawaii on March 4, 1893. He then started an investigation led by James Henderson Blount, which became known as the Blount Report.

Contents

Why Did the Overthrow Happen?

The Hawaiian Kingdom was taken over because foreigners and their descendants gained more and more control. Many of these foreigners bought land and invested in Hawaii's profitable sugar industry.

In 1887, these foreign businessmen forced King Kalākaua to sign a document called the Bayonet Constitution. This document took away much of his power and made Hawaii a constitutional monarchy. This meant the king's power was limited by a constitution.

Later, in 1890, the United States passed a new law called the McKinley Tariff. This law made imported sugar more expensive, which hurt Hawaii's sugar industry. Hawaiian sugar was no longer as competitive in the U.S. market, causing economic problems for the islands.

After the sugar industry faced difficulties, Queen Liliʻuokalani, who was now the reigning monarch, suggested a new constitution in 1893. This new constitution would give the Queen more power and reduce the power of the foreign businessmen. Most native Hawaiians supported this idea.

However, the Americans and other foreigners living in Hawaii strongly opposed it. They began to plan a takeover. Those against the monarchy formed a group called the Committee of Safety. Meanwhile, those who supported the Queen formed the Committee of Law and Order.

The situation became tense, and both sides started to arm themselves. The United States sent the ship USS Boston to protect American interests. A small group of Marines landed. Even though the Americans were supposed to be neutral and didn't fire any shots, their presence worried the Queen's supporters. Queen Liliʻuokalani, wanting to avoid bloodshed, gave up her power.

What Was the Blount Report?

After the overthrow, President Cleveland wanted to understand what really happened. He removed the U.S. Minister to Hawaii, John L. Stevens, and the captain of the USS Boston. Cleveland then pulled back the treaty that would have made Hawaii part of the U.S., because many Hawaiian citizens were against it. The Provisional Government in Hawaii then became the Republic of Hawaii.

President Cleveland sent James Blount to Hawaii to investigate the situation. Blount's report said that the Provisional Government was not set up with the Hawaiian people's permission. It also claimed that Queen Liliʻuokalani only surrendered because she believed the U.S. supported the new government and she wanted to avoid a bloody conflict. She was told that the U.S. president would look into her case if she surrendered. After reading the report, Cleveland decided not to send the annexation treaty back to the Senate. However, the Provisional Government disagreed with Blount's findings.

What Was Black Week?

Black Week was a time of great tension in Hawaii, starting on December 14, 1893. This was when Albert Willis arrived in Honolulu. Willis was the new U.S. Minister to Hawaii, taking over from James Blount. His arrival caused fear that the U.S. might invade to bring back the monarchy.

Willis made it seem like an American invasion was about to happen. He had U.S. ships, USS Adams and USS Philadelphia, point their guns toward the capital. He also ordered U.S. troops to prepare to land. Ships from Japan and Britain also joined in. The people and the Provisional Government of Hawaii were ready to fight if needed, but many believed Willis was bluffing.

On December 16, 1893, the British were allowed to land marines from HMS Champion to protect British interests. The British captain thought the U.S. military would restore Queen Liliʻuokalani. Earlier, in November 1893, Queen Liliʻuokalani had told Willis she wanted the revolutionaries punished and their property taken away. Willis, however, wanted her to forgive them.

On December 19, 1893, Willis met with the leaders of the Provisional Government. He showed them a letter from Queen Liliʻuokalani, where she agreed to forgive the revolutionaries if she was made queen again. Willis told the Provisional Government to give up power and let Hawaii return to how it was before. But Sanford B. Dole, the leader, refused. He said he was not under the authority of the United States.

A few weeks later, on January 10, 1894, the U.S. Secretary of State, Walter Q. Gresham, announced that the Hawaiian situation would be handled by Congress. He said Willis had not made enough progress. President Cleveland felt Willis had followed his orders exactly but missed the true meaning of them.

On January 11, 1894, Willis confirmed that the threat of invasion had been a trick.

How Did Americans React?

Many Americans did not like what Willis and Cleveland tried to do in Hawaii. Newspapers across the country showed this. The New York Herald said Willis should stop interfering in Hawaiian affairs. The New York World asked if it wasn't time to stop getting involved in other countries' business. The New York Sun said Cleveland wasn't good enough to be a fair judge. The New York Tribune called Willis's trip a "failure." The New York Recorder thought it was wrong to send a minister to a new republic, greet its president, and then try to overthrow that government. Only a few newspapers, like New York Times, defended Cleveland's actions.

Fighting Against Annexation

Queen Liliʻuokalani's Protest

On June 17, 1898, Queen Liliʻuokalani officially protested in Washington, D.C. against the plan to make Hawaii part of the United States.

She stated that the treaty to give Hawaii to the U.S. was wrong for the native Hawaiian people. She said it violated the rights of the chiefs and broke international agreements. The Queen called it a continuation of the fraud that overthrew her government and a great injustice to her.

She reminded everyone that when she surrendered on January 17, 1893, she was told her case would be sent to the United States for a decision. She explained that she gave up her power to U.S. forces to prevent bloodshed, knowing it was useless to fight such a strong power.

The Queen pointed out that U.S. officials had reported that her government was illegally forced out by U.S. forces. They also said she was the rightful ruler of her people.

She argued that the group trying to give Hawaii to the U.S. did not have permission from Hawaiian voters. This group, the Committee of Public Safety, was mostly made up of people claiming to be American citizens, and no native Hawaiians were part of it.

Queen Liliʻuokalani stressed that her people, about 40,000 strong, were not asked about destroying Hawaii's independence. Her people made up four-fifths of the legal voters in Hawaii.

She also mentioned that the treaty ignored the property rights of the chiefs. Out of 4,000,000 acres in Hawaii, about 1,000,000 acres were considered the private property of the monarch. The treaty planned to take this property, called crown lands, without paying those who rightfully owned it.

The Queen said the treaty ignored past agreements of friendship between the U.S. and Hawaiian rulers, and also treaties Hawaii had with other countries. This meant it broke international law.

Finally, she said that by dealing with the group claiming to give Hawaii away, the U.S. government was taking land from people who its own officials had said were illegally in power.

Therefore, Queen Liliʻuokalani asked the U.S. President to withdraw the treaty. She asked the U.S. Senate not to approve it. She also asked the American people to support their leaders in doing what was fair and just.

Efforts by Native Hawaiians

Native Hawaiians strongly opposed becoming part of the U.S. They organized protests through two main groups: Hui Aloha ʻĀina (Hawaiian Patriotic League) and Hui Kālaiʻāina (Hawaiian Political Association). On January 5, 1895, some native islanders tried an armed uprising, but supporters of the Republic of Hawaii quickly stopped it. Those involved, including Queen Liliʻuokalani, were jailed.

In 1897, William McKinley became President of the United States, and he supported annexing Hawaii. A new treaty to make Hawaii part of the U.S. was signed and sent to the U.S. Senate for approval. In response, the Hawaiian Patriotic League and its women's branch gathered signatures against the treaty. In September and October of that year, Hui Aloha ʻĀina collected 21,269 signatures from native Hawaiians. This was more than half of all native residents. Hui Kālaiʻāina also collected about 17,000 signatures to bring back the monarchy, but their petition has been lost.

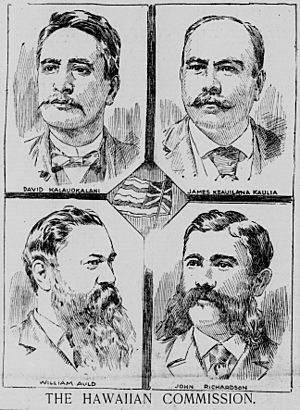

Four Hawaiian delegates—James Keauiluna Kaulia, David Kalauokalani, William Auld, and John Richardson—traveled to Washington, D.C. They presented the Kūʻē Petitions to Congress in December. After showing the petition to the U.S. Senate and talking to senators, they successfully stopped the treaty from being approved in 1898.

However, in 1898, because of the Spanish–American War, the Senate passed the Newlands Resolution. This resolution led to Hawaii becoming a U.S. territory, mainly so it could be used as a military base in the Pacific Ocean.

Images for kids

| Frances Mary Albrier |

| Whitney Young |

| Muhammad Ali |