Kalākaua's 1881 world tour facts for kids

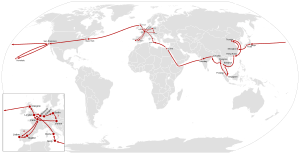

In 1881, King Kalākaua of the Hawaiian Kingdom went on a special trip around the world. He wanted to help the Hawaiian people and their culture. One main goal was to bring new workers to Hawaii from countries in Asia-Pacific. This trip made the small island nation famous among world leaders. Some people in Hawaii thought the king just wanted to travel. But this 281-day journey made Kalākaua the first king to travel all the way around the globe! He had also been the first king to visit the United States in 1874.

Contents

King Kalākaua's World Tour

King Kalākaua met with leaders in Asia, the Middle East, and Europe. He wanted to encourage families and single women to move to Hawaii. These new people would work on the sugar plantations. They would also help the Hawaiian population grow.

In Asia, he talked with Emperor Meiji of Japan. Kalākaua hoped to protect Hawaii from American influence. He even suggested that his niece, Kaʻiulani, could marry a Japanese prince. This would create a strong link between Hawaii and Japan.

While in Portugal, the king signed a friendship and trade agreement. This agreement made it easier for Portuguese workers to move to Hawaii. He also met with Pope Leo XIII in Rome. Kalākaua visited many kings and queens in Europe. He was most impressed by Queen Victoria of Britain. He loved the grand style of European royal families. He later tried to make Hawaii's monarchy just as grand.

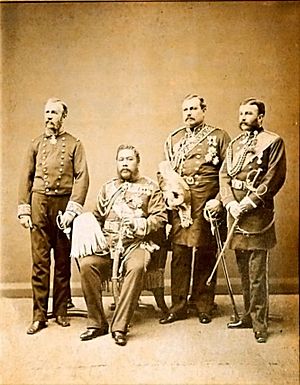

The king traveled with only a few friends. These included Charles Hastings Judd, George W. Macfarlane, and his cook, Robert von Oelhoffen. He did not have a large security team. He usually shared regular steamships and trains with other passengers. On the Red Sea, he even played cards and danced with them!

Like any tourist, he saw many famous sights. He visited the white elephants of Siam (now Thailand). He saw the Giza pyramid complex in Egypt. He also explored tourist spots in India and museums in Europe. The king spent more money than planned, buying many things. He sent letters home to Hawaii.

Return to the United States

When the king returned to the United States, President James A. Garfield had just died. Kalākaua visited the new President, Chester A. Arthur, at the White House. He also visited Thomas Edison to see electric lights. He went to Fort Monroe in Virginia and Hampton Normal and Agricultural School. He even bought horses in Kentucky.

The royal group then took a train to California. They stayed with Claus Spreckels at his home in Aptos. After seeing the sights, they sailed back to Hawaii. The king's trip was a success for immigration. New workers began arriving in Hawaii less than a year later.

After his trip, Kalākaua started to live more like European royalty. He bought expensive furniture for Iolani Palace. He also held a big public coronation for himself. He even had a two-week celebration for his birthday.

Why the King Traveled

King Kalākaua was the last king of the Hawaiian Islands. He had already made history before this world tour. In 1874, he was the first reigning king to visit the United States. He went to Washington, D.C., to discuss a trade agreement. President Ulysses S. Grant hosted the first-ever state dinner at the White House in his honor.

Hawaii was officially called the Hawaiian Kingdom. But it was often known as the Sandwich Islands. This name came from Captain James Cook's visit in 1778. When Cook arrived, about 800,000 Native Hawaiians lived there.

Protecting the Hawaiian People

In the early 1800s, whaling ships and missionaries came to Hawaii. They brought diseases that Hawaiians had never seen before. Many Hawaiians sadly died because they had no protection against these illnesses. By 1878, only about 44,000 people identified as Hawaiian.

King Kalākaua was very worried about this shrinking population. He also needed more workers for the sugar plantations. In 1880, he signed a law to improve the immigration system. He wanted to bring in new people from Asia-Pacific, Europe, and the United States. He hoped these new immigrants would help the Hawaiian population grow again. He especially wanted families and single women to come. This was different from earlier immigration, which mostly brought unmarried men.

King's Traveling Companions

Kalākaua chose William Nevins Armstrong to join his trip. Armstrong had known the king since they were young students. Another friend, Charles Hastings Judd, also joined the tour. Judd was the king's private secretary and chamberlain. The king also brought his personal cook, Robert von Oelhoffen. These three were his only travel companions.

The king told his Cabinet about his plans. He appointed Armstrong as the Royal Commissioner of Immigration. Armstrong's job was to find out which countries could provide good workers for Hawaii. The Minister of Foreign Affairs, William L. Green, sent messages to Hawaii's consulates. These messages explained the goals of the king's trip.

Liliʻuokalani as Regent

King Kalākaua's sister, Liliʻuokalani, was next in line to the throne. She became the Regent while he was away. This meant she would rule Hawaii in his place. Some political groups tried to limit her power. But she insisted on having full royal authority, and the king agreed.

Before he left, the people of Honolulu held farewell parties for the king. A member of the House of Nobles, John Mākini Kapena, spoke at Kawaiahaʻo Church. He said that the world would respect Hawaii even more after the king's trip. People sang traditional Hawaiian songs and chants outside the palace all night.

The king was a Mason. This connection helped him feel part of a global brotherhood during his travels. On January 20, he boarded the steamship City of Sydney for San Francisco. Many people reached out to touch him as he left. He traveled as "Aliʻi Kalākaua" or "Prince Kalākaua." This made it seem like a personal vacation. It helped avoid the large, expensive group needed for an official state visit. The Royal Hawaiian Band and the Hawaiian army waved goodbye as the ship sailed away.

Impact of the Tour

Not everyone was happy about Kalākaua's journey. His sister, Liliʻuokalani, later wrote about how some people criticized him. They thought he was just using the idea of bringing in workers as an excuse to travel the world.

The Pacific Commercial Advertiser newspaper wrote about the king's trip at the end of 1881. They hoped the tour would make Hawaii's future more secure as an independent nation. The newspaper also praised Liliʻuokalani for being a strong and capable ruler while her brother was away. They agreed that Kalākaua had brought Hawaii to the world's attention. He was praised for his leadership and for meeting with global leaders. The newspaper also noted that more books and articles about Hawaii were being published worldwide.

The king's trip cost the government about $22,500. But his own letters show he spent more than that. The exact total cost is not known. He also gave out many awards and decorations during his trip, which cost the kingdom more money.

A Grand Palace

The grand style of European monarchies really impressed King Kalākaua. Iolani Palace was being built in Hawaii while he was on his tour. The king had already been living there before he left. He wanted the palace to look like the grand European palaces. He bought very expensive furnishings for it. The final cost of the palace was much higher than first planned.

A few years later, Iolani Palace was the first place in Hawaii to get electric lights. The king invited the public to see the lights turn on for the first time. About 5,000 people came! The Royal Hawaiian Band played music, and the king rode his horse around the grounds.

Coronation and Celebrations

The king's spending to make Hawaii's monarchy like Europe's added to the country's debt. It increased the monarchy's costs by 50%. Kalākaua decided to have a grand coronation ceremony. He had been denied one when he was first elected king. In 1883, on his 9th year in office, a big public coronation was held. It cost over $50,000. Kalākaua crowned himself. In 1886, his 50th birthday celebration, called a Jubilee, added another $75,000 to the costs.

These expenses were not the only reason for the 1887 Constitution of the Hawaiian Kingdom, but they were part of a pattern of high spending. This spending, often encouraged by his Prime Minister Walter Murray Gibson, eventually led to the king being forced to sign a new constitution. One example of this spending was the $100,000 purchase of a steamboat. This boat was for travel to the Kingdom of Samoa. Kalākaua wanted to form a Polynesian Confederation, a group of Pacific islands working together.

Images for kids

| DeHart Hubbard |

| Wilma Rudolph |

| Jesse Owens |

| Jackie Joyner-Kersee |

| Major Taylor |