Rough Riders facts for kids

Quick facts for kids First U.S. Volunteer Cavalry Regiment |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Active | 1898 |

| Country | United States |

| Branch | United States Army |

| Type | Cavalry |

| Size | 1,060 soldiers 1,258 horses |

| Nickname(s) | Rough Riders |

| Engagements | Spanish–American War |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders |

Leonard Wood Theodore Roosevelt |

The Rough Riders was a special nickname. It was given to the 1st United States Volunteer Cavalry. This group was one of three volunteer regiments formed in 1898. They were created for the Spanish–American War. The Rough Riders were the only volunteer group to actually fight in the war.

At that time, the United States Army was quite small. It was not as organized as it had been during the American Civil War. After the ship USS Maine sank, President William McKinley needed a strong army fast. He asked for 125,000 volunteers to help in the war. The U.S. went to war because of Spain's control over Cuba. Cuba was having a rebellion at the time.

The regiment also had another nickname: "Wood's Weary Walkers." This was because of their first leader, Colonel Leonard Wood. Even though they were a cavalry unit (soldiers who fight on horseback), they fought in Cuba as infantry (soldiers who fight on foot). Their horses could not be sent with them.

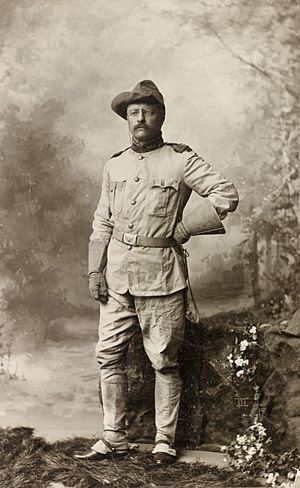

Wood's second-in-command was Theodore Roosevelt. He had been the Assistant Secretary of the Navy. Roosevelt strongly supported Cuba's fight for independence. When Wood was promoted, the group became known as "Roosevelt's Rough Riders." This name came from Buffalo Bill, who called his Western show "Buffalo Bill's Wild West and Congress of Rough Riders of the World."

The original plan was for the regiment to be made of frontiersmen. These were people from the Indian Territory, New Mexico Territory, Arizona Territory, and Oklahoma Territory. But when Roosevelt joined, the group became a mix of different people. It included Ivy League athletes, singers, Texas Rangers, and Native Americans. Everyone who joined had to be a good horse rider. They also had to be eager to fight.

The Rough Riders became very famous. They got more attention than any other army unit in that war. They are best remembered for their actions during the Battle of San Juan Hill. However, it's often forgotten how many more Rough Riders there were compared to the Spanish soldiers they fought. A few weeks after the Battle of San Juan Hill, the Spanish fleet left Cuba. Soon after, a peace agreement was signed, ending the fighting. Even though their service was short, the Rough Riders became legendary. This was largely thanks to Roosevelt writing his own story of the regiment. Silent films made years later also helped.

Contents

Forming the Rough Riders

Gathering the Volunteers

Volunteers for the Rough Riders came from four main areas. These were Arizona, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Texas. They were mostly from the Southwest. This was because the hot climate there was like Cuba's. This meant the men were used to the conditions where they would fight. It was hard to choose men because so many wanted to join. The limit for volunteer cavalrymen was quickly met.

News of Spanish actions and the sinking of the USS Maine made many men want to join. They came from everywhere to show their patriotism. The group included a mix of people. There were cowboys, gold miners, hunters, gamblers, Native Americans, and college students. All of them were strong and good at riding horses and shooting. About half the unit came from New Mexico, according to Roosevelt. The group also had police officers and military veterans. These older men wanted to fight again. Many had already retired.

Since there hadn't been a big war for 30 years, men who had served before wanted to be officers. They had the experience to lead and train the new soldiers. So, the unit had many experienced leaders. Leonard Wood, an Army doctor, became the colonel of the Rough Riders. Roosevelt served as his second-in-command, a lieutenant colonel. A famous place where volunteers gathered was the Menger Hotel Bar in San Antonio, Texas. This bar is still open today. It honors the Rough Riders and Theodore Roosevelt with uniforms and memories.

Weapons and Gear

Before training started, Lieutenant Colonel Roosevelt used his connections. He was Assistant Secretary of the Navy. He made sure his volunteer regiment got good equipment. They were armed like regular Army units. The Rough Riders used Model 1896 Carbines. These were powerful rifles. They also got their cartridges, revolvers, clothes, tents, and horse gear. Their main rifle was the Springfield Krag carbine. This was the same one used by the regular cavalry. The Rough Riders also carried Bowie knives. A rich donor gave them a last-minute gift. It was a pair of modern machine guns.

The uniforms were special for the Rough Riders. They wore a slouch hat, a blue flannel shirt, and brown trousers. They also had leggings and boots. They tied handkerchiefs loosely around their necks. They looked exactly like a group of cowboy cavalry. This "rough and tumble" look helped them earn the name "The Rough Riders."

Training for Battle

Training for the Rough Riders was standard for a cavalry unit. They practiced basic military drills. They learned rules for behavior, obedience, and manners. The men were eager to learn. Training went smoothly. It was decided they would not train with sabers (swords). They had no experience with them. Instead, they used their carbines and revolvers as their main weapons.

Most of the men were already good horse riders. But officers improved their riding skills. They practiced shooting from horseback. They also trained in formations and small battles. High-ranking officers studied books on tactics and drills. This helped them lead the men better. Even when they couldn't do physical drills, like on a train or ship, they read books. This way, no time was wasted in preparing for war. The good training helped the volunteers get ready for their duty.

However, gathering so many troops from different places led to many deaths from disease. Typhoid fever was a big problem. Over 5,000 soldiers died from disease during the Spanish–American War. Many of these deaths happened in training camps in the U.S.

Fighting in the Spanish–American War

Leaving for Cuba

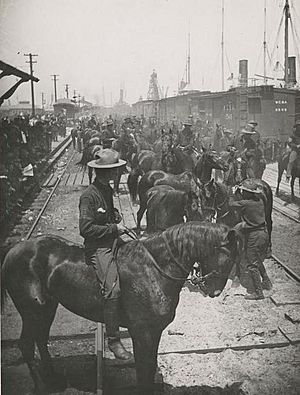

On May 29, 1898, 1,060 Rough Riders and 1,258 horses and mules headed to the railroad. They traveled to Tampa, Florida. From there, they would sail to Cuba. They waited for orders from Major General William Rufus Shafter. Washington D.C. pushed General Shafter to send the troops early. There wasn't enough space on the ships. Because of this, only eight of the 12 companies of Rough Riders could leave Tampa. Many horses and mules were left behind.

Lieutenant-Colonel Roosevelt wrote about the sadness of the men left behind. This situation also weakened the troops early. About a quarter of the trained men were already lost. Most died from malaria and yellow fever. This meant the remaining troops went to Cuba with fewer men and lower spirits.

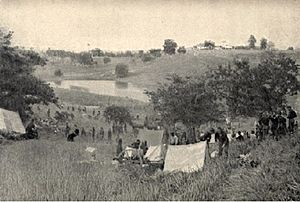

When they arrived in Cuba on June 23, 1898, the men quickly unloaded. They set up camp nearby. They waited for orders to move forward. More supplies were unloaded the next day. This included the few horses allowed on the trip. Roosevelt later wrote that the biggest problem was not enough transportation. He said if they had their mule-train, they could have supplied the whole cavalry. Each man could only carry a few days' worth of food. This food had to last longer and give them energy for hard tasks.

Even with only 75% of the cavalrymen allowed into Cuba, they were still without most of their horses. They had trained as cavalry, not infantry. They were not used to long marches. Especially not in hot, humid, and thick jungle conditions. This was a big disadvantage for the men before they even saw combat.

Battle of Las Guasimas

Within a day of setting up camp, men were sent to explore the jungle. Soon, they returned with news of a Spanish outpost called Las Guasimas. That afternoon, the Rough Riders were ordered to march towards Las Guasimas. Their goal was to remove the Spanish. This would clear the path for the American army to advance. When they reached their destination, the men slept near the Spanish outpost. They would attack early the next morning.

The American side included the 1st U.S. Volunteer Cavalry (Rough Riders). It was led by Leonard Wood. Also present were the 1st U.S. Regular Cavalry and the 10th U.S. Regular Cavalry. The 10th Cavalry had Afro-American soldiers, called Buffalo soldiers then. With artillery support, the American forces had 964 men.

The Spanish had an advantage. They knew the jungle trails well. They guessed where the Americans would walk. They knew where to fire. They also used the land and cover to hide. Their guns used smokeless powder. This meant their firing position was not given away. This made it harder for U.S. soldiers to find them. In some places, the jungle was too thick to see far.

Rough Riders on both sides of the trail moved forward. They pushed the Spanish back to their second line of trenches. The Rough Riders kept advancing. They eventually forced the Spanish to leave their final positions. Rough Riders from A Troop joined regular soldiers. They helped capture the Spanish positions on a long hill. Both Rough Riders and Regulars met at the bottom of the hill. It was about 9:30 a.m. Reinforcements arrived 30 minutes later.

General Samuel Baldwin Marks Young led the attack. He used large Hotchkiss guns. He fired at the hidden Spanish soldiers. Colonel Wood's men, with Lieutenant-Colonel Roosevelt, were not near the others at first. They had a harder path. They had to climb a very steep hill. Many men were tired from the march. They found the climb too hard. Some dropped their gear or left the line. So, fewer than 500 men went into battle. Lieutenant-Colonel Roosevelt saw that men could easily leave without being noticed. The jungle was too thick to see through. This meant even fewer men were left.

Still, the Rough Riders pushed forward with the regulars. Officers carefully watched. They found where the Spanish were hiding. They targeted their men well to defeat them. Near the end of the battle, Edward Marshall, a newspaper writer, was inspired. He picked up a rifle and fought with the soldiers. He was shot in the spine. Another soldier thought he was Colonel Wood. He ran back to report Wood's death. Because of this mistake, Roosevelt temporarily took command. He gathered the troops with his strong leadership.

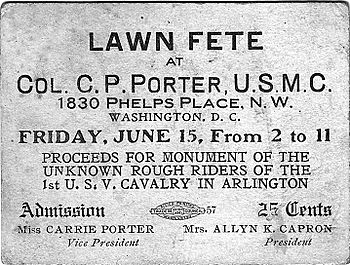

The battle lasted an hour and a half. The Rough Riders had eight dead and 31 wounded. This included Captain Allyn K. Capron Jr.. After the battle, Roosevelt found Colonel Wood alive and well. He then stepped down to his lieutenant-colonel position.

The United States gained full control of this Spanish outpost. It was on the road to Santiago. General Shafter made the men hold their position for six days. More supplies were brought ashore during this time. The Rough Riders ate, slept, cared for the wounded, and buried the dead. Some men died from fever during these six days. General Joseph Wheeler also got sick. Brigadier General Samuel S. Sumner took command of the cavalry. Wood became a brigadier general. This made Roosevelt the colonel of the Rough Riders.

Battle of San Juan Hill

The men were ordered to march eight miles to Santiago. Colonel Roosevelt and his men had no specific orders at first. They were to march to the base of San Juan Heights. Over 1,000 Spanish soldiers defended this area. The Rough Riders were to keep the enemy busy. This would force the Spanish to stay put while American artillery fired at them. The main attack would be by Brigadier General Henry Lawton's division. They would attack the Spanish fort El Caney, a few miles away. The Rough Riders were supposed to meet them during the battle.

San Juan Hill and another hill were separated by a small valley. A pond and river were near the bottom of both hills. Together, these formed San Juan Heights. The battle started with artillery firing at the Spanish. When the Spanish fired back, the Rough Riders had to move quickly. They were in the same area as their own artillery. Colonel Roosevelt and his men went to the bottom of Kettle Hill. It was named for old sugar cauldrons there. They took cover by the riverbank and in tall grass. This helped them avoid sniper and artillery fire. But they were still stuck and vulnerable.

Spanish rifles could fire eight shots in 20 seconds. American rifles took that long to reload. Luckily, the Spanish fired 7mm Mauser bullets. These moved fast and made small, clean wounds. Some men were hit, but few were killed or badly wounded.

Theodore Roosevelt was unhappy. General Shafter had not scouted the area well. He also didn't give clear orders. Roosevelt didn't like his men sitting in the line of fire. He sent messengers to find a general. He wanted orders to advance. Finally, the Rough Riders got orders to help the regular soldiers. They were to attack the front of the hill. Roosevelt, riding his horse, got his men ready to go up the hill. He later said he wanted to fight on foot, like at Las Guasimas. But it would be too hard to supervise his men that way. He also knew he could see his men better from his horse. And they could see him better too.

Roosevelt told his men not to leave him alone during the charge. He drew his pistol. He told nearby black soldiers, separated from their units, that he would shoot them if they turned back. He warned them he kept his promises. The soldiers laughed and joined the volunteers. They got ready for the attack.

The troops slowly moved up the hill. They fired their rifles as they climbed. Roosevelt spoke to the captain of the platoons in the back. He thought they couldn't take the hill effectively. They couldn't return fire well enough. The solution, he said, was to charge. The captain repeated his colonel's orders to hold position. Roosevelt saw the other colonel was not there. He declared himself the highest-ranking officer. He ordered a charge up Kettle Hill. The captain hesitated. Colonel Roosevelt rode off on his horse, Texas. He led his own men uphill, waving his hat and cheering. The Rough Riders followed him with excitement.

Other men from different units on the hill were stirred by this. They began running up the hill with their countrymen. The "charge" was actually short rushes by mixed groups of regulars and Rough Riders. Kettle Hill was taken within 20 minutes. But many soldiers were hurt or killed. The rest of San Juan Heights was taken within the next hour.

The Rough Riders' charge on Kettle Hill was helped by heavy fire. Three Gatling Guns fired many bullets into the Spanish trenches. Colonel Roosevelt said the sound of the Gatling guns lifted his men's spirits. He said, "It's the Gatlings, men! Our Gatlings!" The soldiers cheered. Trooper Jesse D. Langdon, who was with Roosevelt, said they wouldn't have taken Kettle Hill without the Gatling guns.

A Spanish counterattack on Kettle Hill was quickly stopped. One of Lt. Parker's Gatling guns, placed on San Juan Hill, killed most of the attackers. Colonel Roosevelt was very impressed by Lt. Parker. He gave him credit for the successful charge. Roosevelt said Parker deserved more credit than anyone else. He saw how useful machine guns could be in battle.

America's war with Spain was called a "splendid little war." For Theodore Roosevelt, it certainly was. His fighting experience was one week of campaigning. Only one day had hard fighting. He said, "The charge itself was great fun." He also said, "Oh, but we had a bully fight." His actions earned him a recommendation for the Congressional Medal of Honor. But politics stopped him from getting it. This upset Roosevelt. Still, his fame from the charge helped him become governor of New York in 1899. The next year, Roosevelt became Vice President. When President McKinley was killed in 1901, Roosevelt became president.

Half of the Rough Riders were left behind in Tampa. Most of their horses were too. So, the volunteers charged up San Juan Hill on foot. The 10th (Negro) Cavalry joined their attack. The 10th Cavalry never got as much glory as the Rough Riders. But one of their commanders, Captain "Black Jack" Pershing, won the Silver Star. He later led American troops in World War I.

Siege of Santiago

The Rough Riders played an important part in the Spanish–American War. They helped American forces surround the city of Santiago de Cuba. The main goal was to capture San Juan Heights. This would give them a good position to attack Santiago. Santiago was a strong Spanish military point. The Spanish had a fleet of warships in port. The United States drove these ships out by taking areas around Santiago. Then they moved in on the city from many directions.

Two days after the battle on San Juan Heights, the U.S. navy destroyed Spain's warship fleet. This happened at Santiago Bay. This was a huge blow to the Spanish military. They relied heavily on their navy.

The main goal of the American Fifth Army Corps in Cuba was to capture Santiago de Cuba. U.S. forces had pushed back the Spanish at the Battle of Las Guasimas. General Arsenio Linares then moved his troops back to Santiago's main defense line. This was along San Juan Heights. In the charge at the Battle of San Juan Hill, U.S. forces captured the Spanish position. On the same day, at the Battle of El Caney, U.S. forces took another Spanish fort. This allowed them to extend the U.S. line on San Juan Hill. The destruction of the Spanish fleet meant U.S. forces could safely surround the city.

But the sinking of the Spanish ships did not end the war. Battles continued in and around Santiago. On July 16, both governments agreed to surrender terms. General Toral surrendered his troops in Santiago. This included 9,000 soldiers. The Spanish also gave up Guantanamo City and San Luis. The Spanish troops marched out of Santiago on July 17. By July 17, 1898, the Spanish forces in Santiago surrendered to General Shafter.

Various battles in the region continued. The United States kept winning. On August 12, 1898, the Spanish Government surrendered. They agreed to a peace treaty. This treaty gave the U.S. control of Cuba. It also gave the U.S. the territories of Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines. This large amount of new land made the United States a powerful nation. The Spanish–American War also started a trend. The United States began getting involved in other countries' affairs. This has continued to today.

After the War

Coming Home

On August 14, the Rough Riders arrived at Montauk Point in New York. There, they met the four companies that had stayed behind in Tampa. Colonel Roosevelt noted that many of the men left behind felt bad. They felt guilty for not fighting in Cuba. However, he also said that those who stayed did their duty. He said glory was not as important as doing what was ordered.

For the first part of the month in Montauk, the men received hospital care. Many men had malarial fever. It was called "Cuban fever" then. Some died in Cuba. Others were brought back to the U.S. on ships in makeshift quarantine. Malaria was a problem because it kept coming back. Some men died after returning home. Many were very sick. Besides malaria, there were cases of yellow fever, dysentery, and other sicknesses. Many men were very tired. They were in poor health when they came home. Some had lost 20 pounds. Everyone got fresh food. Most got back to their normal health.

The rest of the month in Montauk, New York was spent celebrating. The regiment received three mascots. One was a mountain lion named Josephine. She was brought by troops from Arizona. Another was a war eagle named after Colonel Roosevelt. New Mexican troops brought him. The last was a small dog named Cuba. He had come on the journey overseas. A young boy had also hidden on the ship before it left for Cuba. He was found with a rifle and ammunition. He was sent ashore before leaving the U.S. The regiment left behind took him in. They gave him a small Rough Riders uniform. He became an honorary member.

The men also honored their colonel. They gave him a small bronze statue. It was called "Bronco Buster." It showed a cowboy riding a bucking horse. Roosevelt said it was the perfect gift from such a regiment. He said most of them were experts at riding wild horses. After giving their gift, every man shook Colonel Roosevelt's hand and said goodbye.

Saying Goodbye to the Rough Riders

On September 15, 1898, the Rough Riders' property was returned to the U.S. government. This included all equipment, guns, and horses. The soldiers said one last goodbye to each other. The United States First Volunteer Cavalry, Roosevelt's Rough Riders, was officially ended. Before they went home, Colonel Roosevelt gave a short speech. He praised their efforts. He told them how proud he was. He reminded them that even though they were heroes, they had to go back to normal life. They had to work hard like everyone else.

Many men could not get their old jobs back. Some could not work because of illness or injury. Some rich supporters gave money to help the veterans. But many were too proud to accept it.

The first reunion of the Rough Riders was held in 1899. It was at the Plaza Hotel in Las Vegas, New Mexico. Roosevelt, who was then Governor of New York, attended. Roosevelt spoke about the New Mexicans and Southwesterners in the Rough Riders. He said, "The majority of you Rough Riders came from the Southwest. I shall ever keep in mind the valor you showed as you charged up the slope of San Juan Hill. I owe you men. . . . If New Mexico wants to be a state, I will go down to Washington to speak for her and do anything I can."

Roosevelt strongly supported statehood for Oklahoma, New Mexico, and Arizona. He did this during his time in the Oval Office. He even made it part of the Republican party's plan in 1900.

In 1948, 50 years after the Rough Riders ended, the U.S. Post office made a special stamp. It honored the Rough Riders. The stamp shows Captain William Owen "Bucky" O'Neill. He was killed while leading his troop at the Battle of San Juan Hill on July 1, 1898. The Rough Riders continued to have yearly reunions in Las Vegas until 1967. Only one veteran, Jesse Langdon, attended that year. He died in 1975.

Last Surviving Rough Riders

The last three surviving veterans of the regiment were Frank C. Brito, Jesse Langdon, and Ralph Waldo Taylor.

Brito was from Las Cruces, New Mexico. His father was a Yaqui Indian who operated a stagecoach. Brito was 21 when he joined with his brother in May 1898. He never went to Cuba. He was part of H Troop, one of the four left behind in Tampa. He later became a mining engineer and a lawman. He died on April 22, 1973, at age 96.

Langdon was born in 1881 in what is now North Dakota. He traveled to Washington, D.C. and visited Roosevelt at the Navy Department. He reminded Roosevelt that his father, a veterinarian, had treated Roosevelt's cattle. Roosevelt arranged a train ticket for him to San Antonio. Langdon joined the Rough Riders at age 16. He was the second-to-last surviving member. He was the only one to attend the last two reunions, in 1967 and 1968. He died on June 29, 1975, at age 94.

Taylor was only 16 in 1898. He lied about his age to join the New York National Guard. He served in Company K of the 71st Infantry Regiment. He died on May 15, 1987, at age 105.

Rough Riders in World War I

After the United States joined World War I, Congress gave Roosevelt permission. He could raise up to four divisions like the Rough Riders. Roosevelt wrote in his book Foes of Our Own Household (1917) that he had this authority. He had chosen 18 officers to recruit volunteers. This was soon after the U.S. entered the war. However, President Wilson ultimately said no to Roosevelt's plan. He refused to use the volunteers. So, Roosevelt ended the unit.

One of Roosevelt's trusted officers from the Rough Riders was Brigadier General John Campbell Greenway. He served in the 101st Infantry Regiment in World War I. Greenway was praised for his brave actions in battle. He was honored for his courage at Cambrai. France gave him the Croix de Guerre and the Legion of Honor. He also received the Ordre de l'Étoile Noire. This was for leading the 101st Infantry Regiment during the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. He also received a Distinguished Service Cross.

Rough Rider Facts

Here are some facts about the Rough Riders:

- Joined Up:

- Officers: 56

- Enlisted Men: 994

- Left Service:

- Officers: 76

- Enlisted Men: 1,090

- Total Counted When Leaving:

- Officers: 52

- Enlisted Men: 1,185

- Losses During Service:

- Officers: 5 (2 killed in action, 1 died of disease, 2 resigned/discharged)

- Enlisted Men: 95 (21 killed in action, 3 died of wounds, 19 died of disease, 31 discharged by order, 9 discharged for disability, 12 deserted)

- Wounded:

- Officers: 7

- Enlisted Men: 97

Rough Riders in Pop Culture

Shows and Plays

Colonel Theodore Roosevelt and the Rough Riders were popular in shows. They appeared in Wild West shows like Buffalo Bill's Wild West and Congress of Rough Riders of the World. They were also in minstrel shows like William H. West's Big Minstrel Jubilee. Roosevelt himself helped make the Rough Riders famous. He hired Mason Mitchell, a fellow Rough Rider, to perform for a political group.

More than anyone, William Frederick Cody helped create the dramatic story of the Rough Riders. His shows made it exciting for audiences. They helped keep the legends alive. The idea of the "cowboy" became popular. For Roosevelt, the strong, free life of the Western cowboy was a perfect answer to city life.

On Television

In 1997, a TV miniseries called Rough Riders aired. It was shown over two nights. The series was directed by John Milius. It mainly focused on the Battle of San Juan Hill.

In the TV show M*A*S*H, Colonel Sherman Potter joked. He claimed he rode with Theodore Roosevelt when he was 15 years old.

In Movies

The Rough Riders is a silent film. It was released in 1927. Victor Fleming directed it.

See also

In Spanish: Rough Riders para niños

In Spanish: Rough Riders para niños

| Precious Adams |

| Lauren Anderson |

| Janet Collins |