1911 Revolution facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Xinhai Revolution辛亥革命 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Anti-Qing Movements | |||||||

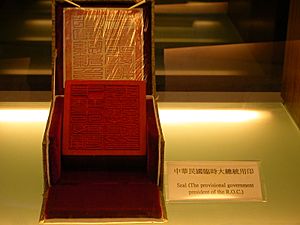

Nanjing Road (Nanking Road) in Shanghai after the Shanghai Uprising, with Five Races Under One Union flags used by revolutionaries. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 200,000 |

100,000 unknown |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| ~170,000 |

~50,000 unknown |

||||||

| 1911 Revolution | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

"Xinhai Revolution" in Chinese characters

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 辛亥革命 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "Xinhai (stem-branch) revolution" | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

The 1911 Revolution, also known as the Xinhai Revolution, was a major event that ended China's last imperial dynasty, the Qing dynasty. This revolution led to the creation of the Republic of China. It was the result of many protests and uprisings over ten years. Its success meant the end of over 2,000 years of emperors ruling China. It also marked the end of the Qing dynasty's 276-year rule and the start of China's republican era.

The Qing dynasty had tried for a long time to change its government and fight off foreign powers. However, their reform plans after 1900 were seen as too fast by some and too slow by others. Different groups, including secret anti-Qing groups and revolutionaries living outside China, debated how to overthrow the Qing dynasty. The revolution officially began on October 10, 1911, with the Wuchang Uprising. This was a rebellion by soldiers in the New Army. Soon, similar revolts happened across the country, and provinces declared themselves free from Qing rule. On November 1, 1911, the Qing court made Yuan Shikai, a powerful general, their Prime Minister. He then started talking with the revolutionaries.

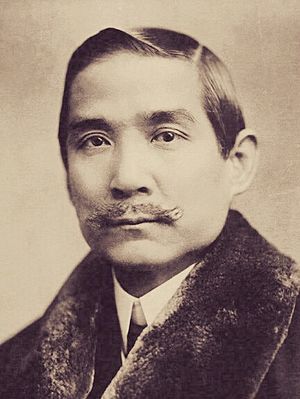

In Nanjing, the revolutionary forces formed a temporary government. On January 1, 1912, the National Assembly announced the Republic of China was established. Sun Yat-sen, a key leader, became its first President. A short civil war between the North and South ended in an agreement. Sun Yat-sen would step down for Yuan Shikai if Yuan could get the Qing emperor to give up his throne. The official order for the six-year-old Xuantong Emperor to step down was issued on February 12, 1912. Yuan Shikai became president on March 10, 1912.

In December 1915, Yuan Shikai tried to bring back the monarchy and declared himself emperor. But many people and the army were against this. He had to give up his emperor title in March 1916, and the Republic was brought back. Yuan died in June 1916 without making the central government strong. This led to many years of political chaos and rule by different warlords. There was even another attempt to bring back the Qing dynasty.

The revolution is called Xinhai because it happened in 1911. This was the year of Xinhai (辛亥) in the traditional Chinese calendar. Both the Republic of China (on island of Taiwan) and the People's Republic of China (on the Chinese mainland) see themselves as carrying on the spirit of the 1911 Revolution. They both value the revolution's ideas like nationalism, republicanism, and modernization of China. In Taiwan, October 10 is celebrated as Double Ten Day. In mainland China, it's the Anniversary of the 1911 Revolution.

Contents

Why the Revolution Happened

China faced many problems before 1911. After losing the First Opium War in 1842, the Qing court was slow to change. They didn't want to give power to local leaders. After another defeat in the Second Opium War in 1860, the Qing tried to modernize. They adopted Western technologies in a movement called Self-Strengthening Movement.

The Qing government also relied on local armies to fight rebellions like the Taiping Rebellion (1851–64). Despite efforts to bring in Western technology, China's defeat in the First Sino-Japanese War in 1895 was very embarrassing. This showed many people that China needed deeper changes. The court created the New Army under Yuan Shikai. Many believed that Chinese society itself needed to become modern for new technologies to work.

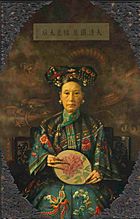

In 1898, the Guangxu Emperor tried to reform China. He worked with reformers like Kang Youwei and Liang Qichao. They suggested big changes in education, military, and the economy. This was called the Hundred Days' Reform. But a group of conservatives, led by Empress Dowager Cixi, quickly stopped these reforms. The Emperor was put under house arrest. Reformers Kang and Liang had to leave the country to avoid being killed.

Empress Dowager Cixi controlled China until she died in 1908. She was supported by officials like Yuan Shikai. In 1900, attacks on foreigners and Chinese Christians, encouraged by the Empress Dowager, led to another foreign invasion of Beijing. This was the Boxer Rebellion.

After this, the Qing court made some basic financial and administrative reforms. But these changes did not gain much trust or support. Many people, like Zou Rong, felt strong anti-Manchu feelings. They blamed the Manchu rulers for China's problems. Kang Youwei and Liang Qichao wanted to bring back the emperor. But others, like Sun Yat-sen, formed revolutionary groups to overthrow the dynasty completely. These groups had to work in secret or from other countries. They gained followers among Overseas Chinese and even within the new armies in China. A severe famine in 1906 and 1907 also added to the unrest.

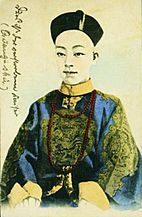

After the Guangxu Emperor and Empress Dowager Cixi died in 1908, the two-year-old Xuantong Emperor took the throne. Prince Chun became his regent. Prince Chun continued the reforms, but conservative Manchu nobles in the court opposed them. This made more people support the revolutionaries.

How the Revolution Was Organized

Early Revolutionary Groups

Many groups wanted to overthrow the Qing government and bring back a Han Chinese-led government. The first revolutionary groups were started outside China. For example, Yeung Ku-wan's Furen Literary Society was created in Hong Kong in 1890.

Sun Yat-sen's Xingzhonghui (Revive China Society) was founded in Honolulu in 1894. Its main goal was to raise money for revolutions. These two groups joined together in 1894.

Other Important Groups

The Huaxinghui (China Revival Society) was started in 1904 by leaders like Huang Xing and Song Jiaoren. Their motto was "Take one province by force, and inspire the other provinces to rise."

The Guangfuhui (Restoration Society) was also founded in 1904 in Shanghai. It was led by Cai Yuanpei. One famous member was Qiu Jin, a woman who fought for women's rights.

Many smaller revolutionary groups existed across different provinces. There were also criminal organizations that were against the Manchu rulers, like the Green Gang and Hongmen. Sun Yat-sen himself was connected with the Hongmen, also known as Tiandihui (Heaven and Earth society).

Another group was the Gelaohui (Elder Brother Society). This group later became closely linked with the Communist Party.

The Tongmenghui

Sun Yat-sen successfully brought together the Revive China Society, Huaxinghui, and Guangfuhui in 1905. This created the unified Tongmenghui (United League) in Tokyo. Sun Yat-sen was the leader of this new, larger group. Most of its members were young, between 17 and 26 years old.

Later Revolutionary Groups

In 1907, some Tongmenghui members in Tokyo formed the Gongjinhui (Progressive Association). In 1911, another group, Zhengwu Xueshe, changed its name to Wenxueshe (Literary Society). These two groups played a big role in the Wuchang Uprising.

Many young revolutionaries also supported anarchist ideas. They believed that simply changing the government wasn't enough. They wanted big cultural changes in family, gender, and social values. Some anarchists, like Wang Jingwei, even thought assassination could help start the revolution. Others believed education was the best way.

Revolutionary Ideas

Many revolutionaries spread strong anti-Qing and anti-Manchu feelings. They reminded people of past conflicts between the Manchu rulers and the Han Chinese majority. In 1904, Sun Yat-sen stated his group's goal: "to expel the Manchu rulers, to revive China, to establish a Republic, and to distribute land equally." Many secret groups used the slogan "Resist Qing and restore Ming."

Who Supported the Revolution?

Many different groups supported the 1911 Revolution. These included students returning from other countries, members of revolutionary groups, Chinese people living abroad, soldiers from the new army, local leaders, and farmers.

Chinese People Living Abroad

Help from Overseas Chinese was very important. Many Chinese living in places like Singapore and Malaysia gave money to support the revolution. Sun Yat-sen was often called the "father of the Chinese revolution" because he reorganized many of these groups.

New Thinkers and Students

The Qing government started new schools and encouraged students to study abroad. Many young people went to places like Japan to study. These students became a new group of thinkers who greatly helped the revolution. Key figures like Huang Xing and Song Jiaoren had studied in Japan. Some, like Zou Rong, wrote books calling for the overthrow of the Manchu rulers.

Local Leaders and Businessmen

Local leaders and businessmen also became powerful. The Qing government tried to let them take part in politics in 1908. These middle-class people first supported a constitutional monarchy. But they became unhappy when the Qing government formed a cabinet mostly made up of Manchu imperial family members.

Foreign Supporters

Some foreigners also supported the 1911 Revolution. Japanese supporters were the most active, with some even joining the Tongmenghui. Miyazaki Touten was a close Japanese supporter of Sun Yat-sen. Homer Lea, an American, advised Sun Yat-sen on military matters.

The Japanese ultra-nationalist Black Dragon Society supported Sun Yat-sen's activities. They believed that overthrowing the Qing would help Japan take over Manchuria. They thought Han Chinese would not resist this takeover. The Black Dragon Society helped Sun Yat-sen unite anti-Manchu groups. They even hosted the first Tongmenghui meeting.

Soldiers of the New Armies

The New Army was created in 1901 after the Qing's defeat in the First Sino-Japanese War. These soldiers were well-trained and equipped. Revolutionaries began to recruit soldiers from these new armies starting in 1908. Sun Yat-sen and his followers secretly joined the New Army.

Key Uprisings and Events

Many uprisings happened, mostly linked to the Tongmenghui and Sun Yat-sen. All uprisings before the Wuchang Uprising failed.

The Wuchang Uprising

The Literary Society and the Progressive Association were key revolutionary groups in this uprising. It began with protests against the Qing government taking over local railway projects and giving them to foreign powers. Some New Army units were sent to Sichuan to stop these protests.

On September 24, the Literary Society and Progressive Association held a meeting in Wuchang. They set up a headquarters for the uprising. The leaders, Jiang Yiwu and Sun Wu, were chosen as commander and chief of staff. They planned the uprising for October 6, 1911, but had to delay it.

On October 9, a bomb accidentally exploded, which was being built by revolutionaries. Sun Yat-sen was in the United States at the time, getting support from Chinese people living abroad. The Qing governor tried to arrest the revolutionaries. But a squad leader named Xiong Bingkun and others decided to start the revolt right away. They launched it on October 10, 1911, at 7:00 p.m. The revolt was successful. Wuchang was captured by the revolutionaries on the morning of October 11. That evening, they formed the "Military Government of Hubei of Republic of China." Li Yuanhong was chosen as the temporary governor. Qing officials were killed by the revolutionary forces.

Changes in Government

Qing Court's Last Efforts

On November 1, 1911, the Qing government appointed Yuan Shikai as Prime Minister. On November 3, the Qing court passed the Nineteen Articles. This changed the Qing from a system where the emperor had all power to a constitutional monarchy. On November 9, Huang Xing even asked Yuan Shikai to join the Republic. But these changes came too late. The emperor was about to step down.

New Government in Nanjing

On November 28, 1911, the Qing army took back Wuchang and Hanyang. So, the revolutionaries held their first meeting in Hankou on November 30. By December 2, the revolutionaries captured Nanjing. They decided to make Nanjing the site of the new temporary government. At this time, Beijing was still the Qing capital.

North-South Peace Talks

On December 18, peace talks were held in Shanghai between the North and South. Foreign bankers did not want to give money to either the Qing government or the revolutionaries. This helped both sides agree to talk. Yuan Shikai sent Tang Shaoyi as his representative. The revolutionaries chose Wu Tingfang. With help from six foreign powers, Tang Shaoyi and Wu Tingfang began to negotiate.

They agreed that Yuan Shikai would make the Qing emperor step down. In return, the southern provinces would support Yuan as President of the Republic. Sun Yat-sen agreed to this plan to unite China under Yuan Shikai's government. They also decided that the emperor could keep his small court in the New Summer Palace. He would be treated like a ruler of a separate country and receive money.

The Republic Is Born

Republic of China Declared

On December 29, 1911, Sun Yat-sen was elected as the first temporary president. January 1, 1912, was set as the first day of the Republic of China. On January 3, Li Yuanhong was recommended as the temporary Vice-president.

During and after the revolution, many groups wanted their own flag for the new nation. The Wuchang military units wanted a nine-star flag. Others suggested Lu Haodong's Blue Sky with a White Sun flag. In the end, they agreed on the Five Races Under One Union flag. This flag had horizontal stripes representing the five main groups of the republic:

Even though the uprisings were against the Manchus, Sun Yat-sen and other leaders wanted all ethnic groups to be united.

Donghuamen Incident

On January 16, Yuan Shikai was attacked with a bomb in Beijing. This attack was organized by the Tongmenghui. About ten guards died, but Yuan was not badly hurt. He sent a message to the revolutionaries, promising his loyalty and asking them to stop trying to assassinate him.

The Emperor Steps Down

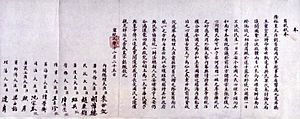

Zhang Jian wrote a proposal for the emperor to step down. On January 20, Wu Tingfang from the Nanjing government officially gave the abdication order to Yuan Shikai. On January 22, Sun Yat-sen announced he would resign as president if Yuan Shikai could get the emperor to step down. Yuan then pressured Empress Dowager Longyu, warning that the imperial family's lives might be in danger if they didn't abdicate. But if they agreed, the new government would honor the terms for the imperial family.

On February 3, Empress Dowager Longyu gave Yuan full permission to negotiate the abdication terms. Yuan then wrote his own version. On February 12, 1912, Puyi (who was six years old) and Empress Dowager Longyu accepted Yuan's terms and the emperor stepped down.

Debate Over the Capital

Sun Yat-sen wanted the temporary government to stay in Nanjing. On February 14, the Provisional Senate first voted to make Beijing the capital. They thought having the capital in Beijing would prevent the Manchus from trying to restore their rule. But Sun and Huang Xing wanted Nanjing to balance Yuan's power in the north.

The next day, the Senate voted again, and this time, they chose Nanjing. Sun sent a group to persuade Yuan to move to Nanjing. Yuan agreed to go south with them. However, on February 29, riots and fires broke out in Beijing. These were supposedly started by soldiers loyal to Yuan. This gave Yuan an excuse to stay in the north to keep order. On March 10, Yuan became the Provisional President of the Republic of China in Beijing. On April 5, the Provisional Senate in Nanjing voted to make Beijing the capital, and they moved there at the end of the month.

The Republican Government in Beijing

On March 10, 1912, Yuan Shikai became the second Provisional President of the Republic of China in Beijing. This government, known as the Beiyang Government, was not fully recognized by other countries until 1928. The first national election happened under the new constitution. The Kuomintang party was formed on August 25, 1912, and won most seats in the election. Song Jiaoren became premier. However, Song was killed in Shanghai on March 20, 1913, likely on Yuan Shikai's secret orders.

What Changed After the Revolution?

Social Impact

After the revolution, there was a strong anti-Manchu feeling across China, especially in Beijing. Thousands died in anti-Manchu violence. Old rules about where Han Chinese could live in the city disappeared as Manchu power fell.

Leaders like Empress Dowager Longyu, Yuan Shikai, and Sun Yat-sen tried to promote the idea of "Manchu and Han as one family." People started thinking about why China had been weak. This led to a new search for identity, known as the New Culture Movement. Sadly, Manchu culture and language almost disappeared by 2007.

Unlike revolutions in the West, the 1911 Revolution did not completely change society. The people who took part, like military leaders and local officials, still held power. Some even became warlords. There were no big improvements in how people lived. The writer Lu Xun noted in 1921 that not much had changed, except "the Manchus have left the kitchen." Economic problems were not fixed until much later.

The 1911 Revolution mainly got rid of the old system of feudalism in China. However, some old ways of thinking returned. For example, the concept of guanxi, or relying on personal connections, became very important.

Because of the anti-Manchu feelings, many Manchus became very poor. Manchu men struggled to find wives, so Han men married Manchu women. Manchus also stopped wearing their traditional clothes and practicing their customs.

Historical Meaning

The 1911 Revolution overthrew the Qing government and ended thousands of years of monarchy in China. Before this, old dynasties were always replaced by new ones. But the 1911 Revolution was the first to completely get rid of the monarchy and try to create a republic with democratic ideas. Sun Yat-sen famously said, "The revolution is not yet successful, comrades still need to strive for the future."

Since the 1920s, the two main Chinese parties – the Republic of China (ROC) and the People's Republic of China (PRC) – see the 1911 Revolution differently. Both Chinas recognize Sun Yat-sen as the "Father of the Nation." In Taiwan, he is seen as the "Father of the Republic of China." On the mainland, Sun Yat-sen is seen as the person who helped bring down the Qing, which was a necessary step for the Communist state founded in 1949. The PRC sees Sun's work as the first step towards the real revolution in 1949, which created a truly independent state.

See also

In Spanish: Revolución de Xinhai para niños

In Spanish: Revolución de Xinhai para niños

- 1911 (film)

- The Battle for the Republic of China

- Military of the Republic of China

- Republic of China calendar

- National Revolutionary Army

- Timeline of Late Anti-Qing Rebellions

- Qiu Jin

- Monarchy of China