Hongwu Emperor facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Hongwu Emperor洪武帝 |

|||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

A Seated Portrait of Ming Emperor Taizu, c. 1377 by an unknown artist from the Ming dynasty. Now located in the National Palace Museum, Taipei, Taiwan.

|

|||||||||||||||||

| 1st Emperor of the Ming dynasty | |||||||||||||||||

| Reign | 23 January 1368 – 24 June 1398 | ||||||||||||||||

| Enthronement | 23 January 1368 | ||||||||||||||||

| Successor | Jianwen Emperor | ||||||||||||||||

| Emperor of China | |||||||||||||||||

| Reign | 1368–1398 | ||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Ukhaghatu Khan Toghon Temür (Yuan dynasty) | ||||||||||||||||

| Successor | Jianwen Emperor (Ming dynasty) | ||||||||||||||||

| Born | Zhu Chongba (朱重八) 21 October 1328 Tianli 1, 18th day of the 9th month (天曆元年九月十八日) Eastern Township, Zhongli County, Hao Prefecture, Anfeng Lu, Henan Jiangbei Province, Yuan dynasty (present-day Randeng Community, Xiaoxihe Town, Fengyang County, Anhui Province); Ancestral home was Gusi Prefecture (present-day Xuyi County, Jiangsu Province) |

||||||||||||||||

| Died | 24 June 1398 (aged 69) Hongwu 31, 10th day of the 5th leap month (洪wu三十一年閏五月初十日) Western Palace, Nanjing Imperial Palace, Shangyuan County, Yingtian Prefecture, Zhili, Ming dynasty (present-day Nanjing, Jiangsu Province) |

||||||||||||||||

| Burial | 30 June 1398 Xiaoling Mausoleum, Nanjing |

||||||||||||||||

| Consorts |

Empress Xiaocigao

(m. 1352; died 1382) |

||||||||||||||||

| Issue |

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

| House | House of Zhu | ||||||||||||||||

| Dynasty | Ming dynasty | ||||||||||||||||

| Father | Zhu Shizhen | ||||||||||||||||

| Mother | Empress Chun | ||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Buddhism | ||||||||||||||||

| Signature |  |

||||||||||||||||

| Hongwu Emperor | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | 洪武帝 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | vastly martial emperor | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

The Hongwu Emperor (born Zhu Yuanzhang on 21 October 1328 – died 24 June 1398) was the first emperor of China's Ming dynasty. He ruled from 1368 to 1398. His personal name was Zhu Yuanzhang, and his courtesy name was Guorui.

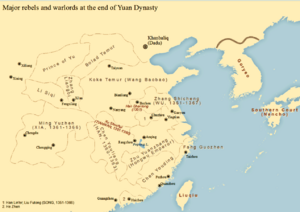

During the 14th century, China faced many problems like famine, plagues, and peasant revolts. Zhu Yuanzhang became a leader of the Red Turban forces. These forces took control of China, ending the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. The Yuan court then moved to the Mongolian Plateau.

Zhu Yuanzhang believed he had the "Mandate of Heaven", which meant he was chosen to rule. He started the Ming dynasty in early 1368. His army took over the Yuan capital, Khanbaliq (now Beijing), that same year. He trusted only his family, so he made his many sons princes in different parts of the empire. When his oldest son, Zhu Biao, died, Zhu Yuanzhang chose Zhu Biao's son to be the next emperor. However, this led to a conflict called the Jingnan Rebellion.

The Hongwu Emperor's time as ruler was known for being open to different groups and religions. For example, he ordered the repair and building of many mosques in cities like Xi’an and Nanjing. He even wrote a famous poem called "Baizi zan" that praised Islam.

Hongwu also made big changes to how the government worked. He got rid of the top government position, the chancellor. He also limited the power of court officials called eunuchs. He put in place very strict rules to stop corruption. He also created the Embroidered Uniform Guard, a famous secret police group in China. In the 1380s and 1390s, he removed many high-ranking officials and generals from power. Many people were punished severely during these times. His reign also saw harsh punishments for crimes and for those who spoke against him.

The emperor encouraged farming and lowered taxes. He also gave rewards for growing crops on new land and made laws to protect farmers' property. He took land from large estates and banned private slavery. At the same time, he made it hard for people to move freely around the empire. He also assigned jobs to families that would be passed down through generations. Through these actions, Zhu Yuanzhang tried to rebuild a country damaged by war. He wanted to control social groups and teach his people traditional values. This created a very organized society of farming communities that could support themselves.

Contents

Early Life of Zhu Yuanzhang

Zhu Yuanzhang was born into a very poor peasant family in Zhongli County. This area is now Fengyang, in Anhui Province. His father was Zhu Shizhen and his mother was Chen Erniang. He had seven older brothers and sisters. His parents sometimes had to give away some of his siblings because they didn't have enough food. When he was 16, a bad drought ruined the crops. A famine followed, which killed everyone in his family except him and one brother.

His grandfather, who lived to be 99, had served in the Southern Song army. This army fought against the Mongol invasion. His grandfather told him many stories about these battles.

After his family died, Zhu had no money. He followed his brother's suggestion and became a young monk at the Huangjue Temple, a local Buddhist monastery. But he had to leave the monastery because it ran out of money.

For the next few years, Zhu lived as a wandering beggar. He saw firsthand how hard life was for ordinary people during the last years of the Yuan dynasty. After about three years, he went back to the monastery. He stayed there until he was about 24 years old. During his time with the Buddhist monks, he learned to read and write.

How Hongwu Rose to Power

The monastery where Zhu lived was later attacked and destroyed by an army. This army was supposed to stop a local rebellion. In 1352, Zhu joined one of the many rebel groups fighting against the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. He quickly moved up in rank and became a commander. His rebel group later joined the Red Turbans. This group was a religious sect linked to the White Lotus Society. It followed traditions from Buddhism, Manichaeism, and other religions. Zhu was seen as a protector of Confucianism among the Han people. He became a key leader of the rebels trying to overthrow the Yuan dynasty.

In 1356, Zhu and his army took over Nanjing. This city became his main base and later the capital of the Ming dynasty during his rule. Zhu's government in Nanjing became known for being well-run. Many people fleeing from other dangerous areas moved to the city. Nanjing's population grew ten times larger over the next 10 years. Meanwhile, the Yuan government was weak because different groups were fighting for control. They didn't try hard to take back the Yangtze River valley. By 1358, central and Southern China were controlled by different rebel groups. The Red Turbans also split up. Zhu became the leader of a smaller group, while a larger group controlled the middle of the Yangtze River valley.

Zhu Yuanzhang was known as the Duke of Wu. He was technically under the control of Han Lin'er, who was the emperor of the Song dynasty.

Zhu was good at attracting talented people to work for him. One person, Zhu Sheng, advised him to "build strong walls, store up food, and wait to claim kingship." Another, Jiao Yu, was an artillery officer who wrote about gunpowder weapons. Liu Bowen became one of Zhu's main advisors and helped write a book about military technology.

From 1360, Zhu and another leader, Chen Youliang, fought a long war. They wanted to control the areas once held by the Red Turbans. A key battle was the Battle of Lake Poyang in 1363. This battle lasted three days. Chen's larger navy was defeated and retreated. Chen died in battle a month later. After this, Zhu stayed in Nanjing and directed his generals from there.

In 1367, Zhu's forces defeated Zhang Shicheng's group, which controlled areas like Suzhou and Hangzhou. This victory gave Zhu's government control over lands north and south of the Yangtze River. Other major warlords surrendered to Zhu. On 23 January 1368, Zhu declared himself emperor of the Ming dynasty in Nanjing. He chose "Hongwu" (meaning "vastly martial") as his era name.

In 1368, Ming armies moved north to attack areas still under Yuan rule. The Yuan emperor, Toghon Temür, left his capital, Khanbaliq (now Beijing), and northern China in September 1368. He retreated to the Mongolian Plateau. In 1371, the Ming dynasty defeated the Ming Xia dynasty in Sichuan.

The Ming army took control of Yunnan, the last Yuan-controlled province, in 1381. This meant that China was finally united under Ming rule.

Hongwu's Reign

Under Hongwu's rule, Chinese officials replaced Mongol and other foreign officials who had been in charge during the Yuan dynasty. The emperor brought back the Confucian civil service imperial examination system. Most government officials were chosen based on their knowledge of literature and philosophy. The Ming exams focused on the Four Books and the teachings of Zhu Xi. The Confucian scholar-bureaucrats, who had less power during the Yuan dynasty, got their important roles back in the government.

Hongwu also made "barbarian" (meaning Mongol-related) things illegal, like certain clothes and names. He also attacked palaces and buildings that the Yuan rulers had used. However, many of Hongwu's government ideas were actually similar to those of the Yuan dynasty. For example, he required community schools for basic education in every village.

Hongwu's legal system had many ways to punish people. One of his generals carried out massacres in some provinces to get revenge on people who fought against his army. Over time, Hongwu became very worried about rebellions. He also ordered the punishment of advisors who criticized him. Religious groups like Manicheanism and the White Lotus Sect, which helped in the revolts against the Yuan, were banned. It is said that he ordered the punishment of several thousand people in Nanjing after hearing someone speak disrespectfully about him. In one famous case, tens of thousands of officials and their families were punished for various charges.

When the Ming dynasty began, Hongwu gave noble titles to his military officers. These titles came with money, but they were mostly symbolic. Special rules were put in place to stop nobles from abusing their power.

Land Reforms

Hongwu came from a peasant family, so he knew how much farmers suffered under powerful officials and the wealthy. Many rich people used their connections to take land from peasants and bribe officials to make the poor pay more taxes. To stop this, he created two systems: Yellow Records and Fish Scale Records. These helped the government collect land taxes and made sure peasants didn't lose their land.

However, these changes didn't completely stop officials from harming peasants. As officials became more powerful and respected, they gained more wealth and didn't have to pay as many taxes. They used their power to take over peasants' lands, often by buying them cheaply or taking them if peasants couldn't pay back loans. Peasants often became tenants, workers, or had to find work elsewhere.

From the start of the Ming dynasty in 1357, Hongwu worked hard to give land to peasants. One way was by moving people to less crowded areas. For example, many migrants came from Hongtong County because it was very crowded. These migrants were gathered under a pagoda tree and taken to nearby provinces. Public projects, like building irrigation systems and dikes, were done to help farmers. Hongwu also reduced the amount of forced labor required from peasants.

In 1370, Hongwu ordered that some land in Hunan and Anhui be given to young farmers who had become adults. This was to stop landlords from taking the land. The order also said that the land titles could not be transferred. Later in his reign, he made a rule that anyone who farmed unused land could keep it without paying taxes. This policy was popular, and by 1393, the amount of farmed land reached a very high level, more than in any other Chinese dynasty. Hongwu also started planting 50 million trees near Nanjing, rebuilt canals, improved irrigation, and helped people move back to the North.

Social Rules

Under Hongwu's rule, rural China was organized into li, which were communities of 110 households. The role of community chief rotated among the ten largest households. The other households were divided into smaller groups called jia. This system was known as lijia. These communities were responsible for collecting taxes and providing labor for the local government. Village elders also had to watch over the community, report crimes, and make sure people were working in agriculture.

The Yuan dynasty's system of categorizing households was continued. The main types were civilian households, military households, craftsmen households, and salt worker households. These categories decided what kind of corvée labor a family had to do. For example, military households had to provide one adult man as a soldier and at least one more person for support roles in the military. These military, craftsmen, and salt worker households were hereditary, meaning they passed down through families. It was very rare to change to a civilian household. Families could also belong to other smaller categories based on their jobs, like physician households or scholar households. There were also categories that were not as good, like entertainer households.

Travelers needed to carry a luyin, a permit from the local government. Their neighbors had to know where they were going. Moving around the country without permission was banned, and those who broke the rule were sent away. This rule was strictly enforced during Hongwu's time.

Zhu Yuanzhang also made a law on 24 September 1392, saying that all men must grow their hair long. It was illegal to shave part of their foreheads, which was a Mongol hairstyle.

Military Power

The Hongwu Emperor knew that the Northern Yuan still posed a threat, even after they were driven out. He decided to change the traditional Confucian idea that military people were less important than scholars. He kept a strong army. In 1384, he reorganized it using a system called weisuo (guard battalion). Each military unit had 5,600 men, divided into five battalions and ten companies. By 1393, there were 1,200,000 weisuo troops. Soldiers were also given land to grow crops, and their positions were passed down through their families.

Training happened in local military areas. During wartime, troops from all over the empire were called up by the Ministry of War. Commanders were chosen to lead them into battle. After the war, the army was broken into smaller groups and sent back to their areas. Commanders had to give their power back to the state. This system helped stop military leaders from becoming too powerful. For large campaigns, the military was controlled by a civilian official, not a general.

Government Changes

Hongwu tried to take full control over all parts of the government. He wanted to make sure no group could become powerful enough to overthrow him. He also strengthened the country's defenses against the Mongols. He gathered more and more power into his own hands. He got rid of the Chancellor's job, which had been the head of the central government in past dynasties. He did this after blaming his chancellor, Hu Weiyong, for a plot. Many people say that Hongwu, wanting complete power, removed the only safeguard against bad emperors.

However, Hongwu couldn't run the huge Ming Empire all by himself. So, he created a new group called the "Grand Secretary". This group, like a cabinet, slowly took on the powers of the abolished prime minister. It eventually became very powerful.

Hongwu also noticed how much trouble court eunuchs had caused in previous dynasties. He greatly reduced their numbers. He forbade them from handling documents, made sure they couldn't read or write, and punished those who talked about state affairs. The emperor really disliked eunuchs. A tablet in his palace said: "Eunuchs must have nothing to do with the administration". However, his successors didn't follow this rule for long.

The Embroidered Uniform Guard was turned into a secret police group during Hongwu's time. It had the power to ignore court rules and could arrest, question, and punish anyone, even nobles and the emperor's relatives.

Through these repeated purges and changes, Hongwu completely changed China's old government structure. He greatly increased the emperor's absolute power.

Legal Changes

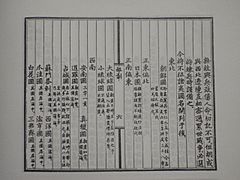

The legal code created during Hongwu's time was seen as a major achievement. The History of Ming says that as early as 1364, the emperor began to write a code of laws. This code was called Da Ming Lü ("Code of the Great Ming"). The emperor spent a lot of time on this project. He told his ministers that the code should be complete and easy to understand. This was to prevent officials from finding loopholes or purposely misinterpreting the laws. The Ming code focused a lot on family relationships. It was also a big improvement over the code of the Tang dynasty in how it treated slaves. Under the Tang code, slaves were treated like animals. If a free person killed a slave, there was no punishment. Under the Ming dynasty, the law protected both slaves and free citizens.

Later in his rule, however, the Code of the Great Ming was replaced by a much harsher legal system called Da Gao ("Great Announcements"). Compared to the Da Ming Lü, the punishments for almost all crimes were much tougher. More than 1,000 crimes could lead to capital punishment. Much of the Da Gao was about the government and officials, especially about stopping corruption. Officials who stole more than about 60 liang (about 30 grams) of silver were to be punished. Zhu Yuanzhang gave all people the right to capture officials suspected of crimes and send them directly to the capital. This was a first in Chinese history. Besides regulating the government, Da Gao also aimed to set limits for different social groups. For example, "idle men" who didn't change their lifestyles after the new law could be punished, and their neighbors sent away. Da Gao also included many sumptuary laws, which were rules about what people could wear or own.

Economic Policies

Hongwu believed that farming should be the country's main source of wealth and that trade was not as important. So, the Ming economic system focused on agriculture. This was different from the Song dynasty, which came before the Yuan dynasty and relied on traders for money. Hongwu also supported creating farming communities that could support themselves.

However, his dislike for merchants did not stop trade. In fact, trade grew a lot during Hongwu's time because industries across the empire expanded. This growth in trade happened partly because of poor soil and too many people in some areas. This forced many people to leave their homes and seek their fortunes in trade.

Although paper money was brought back during Hongwu's era, it didn't work well. Hongwu didn't understand inflation. He gave out so much paper money as rewards that by 1425, the government had to bring back copper coins. This was because the paper money was worth only a tiny fraction of its original value.

Education and Culture

Hongwu tried to remove Mencius from the Temple of Confucius because he thought some parts of his work were harmful. These included ideas like "the people are the most important element in a nation" and "when the prince regards the ministers as the ground or as grass, they regard him as a robber and an enemy." This effort failed because important officials objected. Eventually, the emperor ordered a shorter version of Mencius's work to be made, with 85 lines removed.

At the Guozijian (the national university), Hongwu emphasized law, math, calligraphy, equestrianism (horse riding), and archery. These subjects were also required in the Imperial Examinations, along with Confucian classics. Archery and horse riding were added to the exam in 1370. The area around the Meridian Gate of Nanjing was used for archery practice by guards and generals under Hongwu.

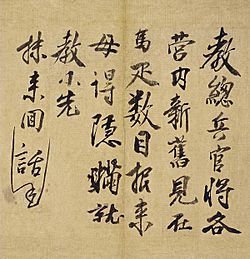

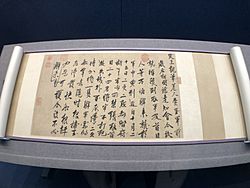

Hongwu wrote essays that were put up in every village across China. These essays warned people to behave or face serious consequences. His writings from the 1380s included the "Great warnings" and the "Ancestral Injunctions". He also wrote the Six Maxims, which later inspired the Sacred Edict of the Kangxi Emperor.

Around 1384, Hongwu ordered the translation of Islamic astronomical tables into Chinese. This work was done by a Muslim astronomer and a Chinese scholar. These tables became known as the Huihui Lifa (Muslim System of Calendrical Astronomy). They were published in China many times until the early 18th century.

Religious Policy

The Code of the Great Ming required Mongol and Central Asian Muslim women and men to marry Han Chinese after Hongwu passed the law.

Hongwu ordered the building of several mosques in provinces like Nanjing, Yunnan, Guangdong, and Fujian. He also had inscriptions praising the Islamic prophet Muhammad placed in them. He rebuilt the Jinjue Mosque in Nanjing, and many Hui people moved to the city during his rule.

Foreign Relations

Hongwu listed 15 countries that the Ming dynasty would not try to conquer. These included Japan, Srivijaya, Siam, Lewchew, and An Nam (Vietnam). He called these the "countries without conquest."

Vietnam

Hongwu did not like to interfere in other countries' affairs. He refused to help the Chams when Vietnam invaded Champa. He only criticized the Vietnamese for their invasion, as he was against military action abroad. He specifically warned future emperors to only defend against foreign groups and not to start wars for glory. In his 1395 ancestral instructions, the emperor clearly wrote that China should not attack Champa, Cambodia, or Annam (Vietnam).

"Japanese" Pirates

Hongwu sent a message to the Japanese saying his army would "capture and exterminate your bandits" and "put your king in bonds." However, many of the "dwarf pirates" raiding his coasts were actually Chinese. Hongwu's response was mostly to try and stop sea trade. Private foreign trade was made illegal and could be punished severely, even affecting the trader's family and neighbors. Ships, docks, and shipyards were destroyed, and ports were damaged. This plan went against Chinese traditions and caused problems. It used up resources and led to 74 coastal garrisons being set up. These were often staffed by local groups. Hongwu's actions reduced tax money, made both Chinese and Japanese people on the coast poorer, and actually increased piracy. Despite the policy, piracy had dropped to very low levels by the time it was officially ended in 1568.

Even so, Hongwu added the sea ban to his Ancestral Injunctions. It continued to be enforced for most of the rest of his dynasty. For the next two centuries, the rich farmlands of the south and the military areas of the north were connected only by the Jinghang Canal.

Despite his deep distrust, Hongwu listed Japan, along with 14 other countries, as "countries against which campaigns shall not be launched" in his Ancestral Injunctions. He advised his descendants to keep peace with them. This policy was broken by his son, the Yongle Emperor, who ordered several actions in Annam (now northern Vietnam). But it remained important for several centuries afterward.

Byzantine Empire

The History of Ming, written during the early Qing dynasty, describes how Hongwu met a merchant from Fulin (the Byzantine Empire) named "Nieh-ku-lun." In September 1371, Hongwu sent the man back to his home country with a letter announcing the founding of the Ming dynasty to his ruler. It is thought that the merchant was actually a former bishop from Beijing. The History of Ming says that contact between China and Fu lin stopped after this point. Diplomats from the great western sea (the Mediterranean Sea) did not appear in China again until the 16th century.

Death of the Hongwu Emperor

After ruling for 30 years, Hongwu died on 24 June 1398, at the age of 69. He was buried at Xiaoling Mausoleum on the Purple Mountain, east of Nanjing.

How Historians See Hongwu

Historians see Hongwu as one of China's most important emperors. As Patricia Buckley Ebrey says, "Seldom has the course of Chinese history been influenced by a single personality as much as it was by the founder of the Ming dynasty, Zhu Yuanzhang." He rose to power very quickly, even though he came from a poor background. In just 11 years, he went from being a monk with no money to the most powerful leader in China. Five years later, he became the emperor of China.

Family

Zhu Yuanzhang had many wives and concubines, including Empress Ma. He had 16 daughters and 26 sons with them.

See also

In Spanish: Zhu Yuanzhang para niños

In Spanish: Zhu Yuanzhang para niños