Srivijaya facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Srivijaya

Kadatuan Śrīvijaya

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 671–1025 | |||||||||

The maximum extent of Srivijaya around the 8th to the 11th century with a series of Srivijayan expeditions and conquest

|

|||||||||

| Capital | Palembang | ||||||||

| Common languages | Old Malay and Sanskrit | ||||||||

| Religion | Mahayana Buddhism, Vajrayana Buddhism, Hinduism and Animism | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy, mandala state | ||||||||

| Maharaja | |||||||||

|

• Circa 683 AD

|

Dapunta Hyang Sri Jayanasa | ||||||||

|

• Circa 775

|

Dharmasetu | ||||||||

|

• Circa 792

|

Samaratungga | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

|

• Dapunta Hyang's expedition and expansion (Kedukan Bukit inscription)

|

c. 671 | ||||||||

|

• Chola invasion of Srivijaya

|

1025 | ||||||||

| Currency | Early Nusantara coins | ||||||||

|

|||||||||

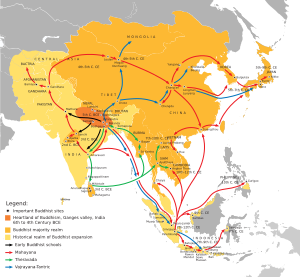

Srivijaya (Indonesian: Sriwijaya) was a powerful Buddhist kingdom based on the island of Sumatra in what is now Indonesia. It greatly influenced much of Southeast Asia. Srivijaya was a key place for spreading Buddhism from the 7th to the 11th century AD. It was the first major power to control a large part of western Maritime Southeast Asia.

Because of its location, Srivijaya became very good at using ocean resources. Its economy relied more and more on the busy trade routes in the region. This made it a center for trading valuable goods.

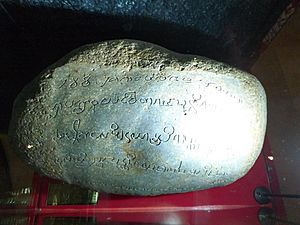

The first mention of Srivijaya is from the 7th century. A Tang dynasty Chinese monk named Yijing wrote that he visited Srivijaya in 671 AD. He stayed there for six months. The oldest known writing that mentions Srivijaya is the Kedukan Bukit inscription. It was found near Palembang, Sumatra, and is dated June 16, 682.

Between the late 7th and early 11th centuries, Srivijaya became a leading power in Southeast Asia. It often had rivalries with nearby kingdoms like Mataram, Khmer, and Champa. Srivijaya's main goal was to have good trade deals with China. These deals lasted from the Tang dynasty to the Song dynasty. Srivijaya also had religious, cultural, and trade connections with the Buddhist Pala Empire in Bengal and the Islamic Caliphate in the Middle East.

At first, people thought Srivijaya was mostly a sea-based empire. But new studies suggest it was mainly a land-based power. Its fleets helped move goods and support its land power. To deal with changes in sea trade and threats from losing control of its areas, kingdoms around the Malacca Straits developed naval strategies. These strategies were mostly to force trading ships to stop at their ports. Later, this turned into raiding other ships.

The kingdom ended in 1025 AD after several attacks by the Chola empire on its ports. After Srivijaya fell, it was mostly forgotten. It wasn't until 1918 that a French historian, George Cœdès, officially said it existed.

Contents

What Does Srivijaya Mean?

Srivijaya is a name that comes from Sanskrit. It means "shining victory" or "glorious." The word Śrī means "fortunate," "prosperous," or "happy." Vijaya means "victorious" or "excellence."

In the early 1900s, historians studying old writings thought "Srivijaya" was a king's name. In 1913, H. Kern was the first expert to find the name "Srivijaya" in a 7th-century Kota Kapur inscription. But he thought it meant a king named "Vijaya" with "Sri" as a royal title.

Later, after studying more writings and Chinese history, historians realized "Srivijaya" was the name of a polity or kingdom. It was a sea-based empire that controlled many semi-independent port cities in Southeast Asia.

How We Know About Srivijaya

Not much physical evidence of Srivijaya remains today. People in Indonesia and Maritime Southeast Asia didn't know much about Srivijaya's history. Foreign scholars helped bring its forgotten past back to light. Even people from Palembang, where the kingdom was based, hadn't heard of Srivijaya until the 1920s. This was when the French scholar, George Cœdès, shared his findings.

Cœdès noticed that Chinese writings about Sanfoqi and old Malay writings were talking about the same empire.

Historians learned about Srivijaya from two main sources. These are Chinese historical records and old stone writings found in Southeast Asia. The Buddhist traveler Yijing's story is very important. He described Srivijaya when he visited in 671 AD. The 7th-century siddhayatra writings found in Palembang and Bangka Island are also key historical sources. Some old tales and legends, like the Legend of the Maharaja of Zabaj and the Khmer King, also give clues about the kingdom. Some Indian and Arabic stories also vaguely describe the great wealth of the king of Zabag.

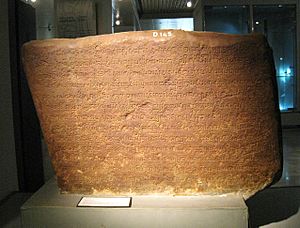

Most of Srivijaya's history was put together from stone writings. Most of these were in Old Malay using the Pallava script. Examples include the Kedukan Bukit, Talang Tuwo, Telaga Batu, and Kota Kapur. Srivijaya became a symbol of Sumatra's early importance. It was seen as a great empire that could stand against Java's Majapahit kingdom. In the 20th century, both empires were used by thinkers to show that an Indonesian identity existed before the Dutch East Indies colonial state.

Srivijaya, and Sumatra, were known by different names to different people. The Chinese called it Sanfotsi or Che-li-fo-che. There was also an older kingdom called Kantoli, which might have been Srivijaya's ancestor. The Arabs called it Zabag or Sribuza. The Khmers called it Melayu. The Javanese called it Suvarnabhumi, Suvarnadvipa, Melayu, or Malayu. These different names made it hard to discover Srivijaya's history.

Where Was the Capital?

Palembang: A Key City

The Kedukan Bukit inscription, from 683 AD, says Srivijaya was first set up near today's Palembang. This was on the banks of the Musi River. It mentions that Dapunta Hyang Sri Jayanasa came from Minanga Tamwan. Where Minanga Tamwan was exactly is still debated. The idea that Palembang was Srivijaya's first capital was suggested by Cœdes.

Many old items have been found west of modern Palembang city. These include Chinese ceramics, Indian pottery, and the remains of stupas (Buddhist shrines) at Bukit Seguntang. Many Hindu-Buddhist statues have also been found in the Musi River area. These findings support the idea that Palembang was Srivijaya's center.

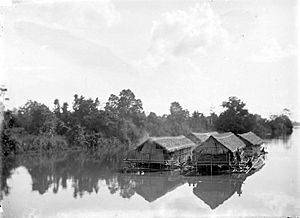

However, Palembang has few signs of old city settlements. This is likely because Palembang is a low-lying area that often floods. Experts think the old Palembang settlement was a group of floating houses made of wood, bamboo, and straw roofs. A Chinese record from the 13th century confirms this. It says that the people of Sanfo-tsi (Srivijaya) lived in scattered houses on the water, on rafts made of reeds. It was probably only the king's court and religious buildings that were on land.

In 1984, an aerial photo near Palembang showed old canals, moats, ponds, and artificial islands. This suggests where Srivijaya's city center might have been. Many items like inscription pieces, Buddhist statues, beads, and Chinese ceramics were found. This confirms that many people once lived there. By 1993, Pierre-Yves Manguin showed that Srivijaya's center was along the Musi River. This area is now part of Palembang. Palembang is called Jù gǎng (Giant Harbour) in Chinese, which might show its past as a great port.

Recent discoveries from the muddy bottom of the Musi River seem to confirm Palembang as Srivijaya's trade center. In 2021, local fishermen found many treasures. These included old coins, gold jewelry, Buddhist statues, gems, colorful beads, and Chinese ceramic pieces. Sadly, these treasures were quickly sold to international dealers before experts could study them.

Jambi: Another Possible Center

Some scholars believe Srivijaya's center was in Muaro Jambi, not Palembang. In 2013, archaeologists found several religious and living sites at the Muaro Jambi Temple Compounds. This suggests that Srivijaya's first center was in Muaro Jambi Regency, Jambi, on the Batang Hari River.

The Muaro Jambi site has eight excavated temples and covers about 12 square kilometers. It stretches 7.5 kilometers along the Batang Hari River. There are also 80 mounds of temple ruins that are not yet restored. The Muaro Jambi site was Mahayana-Vajrayana Buddhist. This suggests it was a Buddhist learning center. Chinese sources also said Srivijaya had thousands of Buddhist monks.

Muaro Jambi has more archaeological sites than Palembang, with many brick temples along the Batang Hari river. No similar temples have been found in Palembang. Supporters of the Muaro Jambi theory say that old descriptions and findings fit Jambi better than the marshy Palembang. They also argue that Jambi, at the mouth of the Batang Hari river, was a center for gold trade. This could explain Srivijaya's famous wealth.

Other Possible Locations

Some theories suggest that Dapunta Hyang came from the east coast of the Malay Peninsula. They think that Chaiya District in Surat Thani Province, Thailand, was Srivijaya's center. There is clear evidence of Srivijayan influence in art there. Because many remains, like the Ligor stele, were found in Chaiya, some scholars tried to prove it was the capital. The city's name, Chaiya, might come from the Malay word "Cahaya," meaning "light." Some Thai historians think it was the capital, but most scholars disagree.

History of Srivijaya

How Srivijaya Began and Grew

The Sacred Journey

Around 500 AD, the Srivijayan empire started to form near today's Palembang, Sumatra. The Kedukan Bukit inscription (683 AD) says that Dapunta Hyang Sri Jayanasa and his group founded Srivijaya. He went on a sacred journey called siddhayatra. He led 20,000 troops and 312 people in boats, plus 1,312 foot soldiers, from Minanga Tamwan to Jambi and Palembang. Many of these fighters were likely sea people, known as the orang laut.

To become powerful, Srivijaya first had to control Southeast Sumatra. This area had many small, independent areas ruled by local chiefs called Datus. Dapunta Hyang Sri Jayanasa launched a sea conquest in 684 AD. He wanted wealth, power, and "magical powers." Under his rule, the Melayu Kingdom was the first to join Srivijaya. This probably happened in the 680s. Melayu, also called Jambi, was rich in gold and highly respected. Srivijaya knew that taking over Melayu would make it more powerful.

The empire had three main parts. These were the capital region around Palembang, the Musi River basin (which provided valuable goods), and other river areas that could become rivals. Areas up the Musi River had many goods that Chinese traders wanted. The ruler directly managed the capital. Local chiefs, or datus, controlled the inland areas. They formed alliances with the Srivijaya maharaja (king). Force was used against rival river systems, like the Batang Hari River in Jambi.

The Telaga Batu inscription, found in Palembang, is also a 7th-century siddhayatra writing. It was likely used in a loyalty ceremony. The stone has seven nāga (snake) heads on top. At the bottom, there is a spout for liquid, probably poured during the ritual. The ritual included a curse against anyone who betrayed Kadatuan Srivijaya.

The Talang Tuwo inscription is another siddhayatra writing. Found in Bukit Seguntang, Palembang, it talks about King Jayanasa creating the beautiful Śrīksetra garden. This garden was for the well-being of all living things. The Bukit Seguntang site was likely where this garden was.

Taking Over Regions

The Kota Kapur inscription from Bangka Island says that Srivijaya conquered most of southern Sumatra and nearby Bangka. It reached as far as Palas Pasemah in Lampung. The writings also say that Dapunta Hyang Sri Jayanasa led a military campaign against Java in the late 7th century. This was when Tarumanagara in West Java and the Kalingga in Central Java were declining. So, the empire grew to control trade in the Strait of Malacca, the western Java Sea, and possibly the Gulf of Thailand.

Chinese records from the late 7th century mention two kingdoms in Sumatra and three in Java as part of Srivijaya. By the end of the 8th century, many kingdoms in western Java, like Tarumanagara and Kalingga, were under Srivijaya's influence.

The Golden Age

In the second half of the 8th century, the Srivijayan area seemed to be ruled by the Sailendra dynasty from Central Java. Some Arabic sources say that Zabag (the Javanese Sailendra dynasty) ruled over Sribuza (Srivijaya). But it's not clear if Srivijaya's capital moved to Java or if Srivijaya just became part of Java.

Control of Malay Peninsula

During the same century, Langkasuka on the Malay Peninsula became part of Srivijaya. Soon after, Pan Pan and Tambralinga, north of Langkasuka, also came under Srivijaya's influence. These kingdoms on the peninsula were important trading nations. They moved goods across the Kra Isthmus.

The Ligor inscription says that Maharaja Dharmasetu of Srivijaya ordered three temples built. These were for the Bodhisattvas Padmapani, Vajrapani, and Buddha in the northern Malay Peninsula.

Sailendra Dynasty's Influence

The Sailendras of Java formed a connection with the Srivijayan rulers in Sumatra. Then, they gained power in the Mataram Kingdom of Central Java. The exact nature of this relationship is unclear. Arabic sources mention that Zabag (Java) ruled over Sribuza (Srivijaya).

In Java, Dharanindra's successor was Samaragrawira (ruled 800–819). The Nalanda inscription (860 AD) says he was the father of Balaputradewa. Unlike Dharanindra, Samaragrawira seemed peaceful. He focused on completing the Borobudur project. He appointed the Khmer Prince Jayavarman II as governor in the Mekong delta. This later proved to be a mistake. Jayavarman II rebelled and declared Khmer independence from Java in 802 AD.

Dewi Tara, the daughter of Dharmasetu, married Samaratunga. He was a Sailendra family member who became the king of Srivijaya around 792 AD. By the 8th century, the Srivijayan court was almost in Java. The Sailendra king became the Maharaja of Srivijaya.

After Dharmasetu, Samaratungga became the next Maharaja of Srivijaya. He ruled from 792 to 835 AD. He did not expand militarily. Instead, he focused on strengthening Srivijaya's control of Java. He oversaw the building of the huge Borobudur monument, which was finished in 825 AD. Samaratungga seemed to be deeply influenced by peaceful Mahayana Buddhist beliefs. His successor was Princess Pramodhawardhani. She married the Shivaite Rakai Pikatan. This marriage was likely an effort to bring peace and secure Sailendra rule in Java.

Srivijaya Returns to Palembang

Prince Balaputra did not agree with Pikatan and Pramodhawardhani ruling in Central Java. Historians have different ideas about Balaputra and Pramodhawardhani's relationship. An older idea says Balaputra was Samaratungga's son, making him Pramodhawardhani's younger brother. Later historians say Balaputra was Samaragrawira's son and Samaratungga's younger brother, making him Pramodhawardhani's uncle.

It is not known if Balaputra was forced out of Central Java because of a fight over who would rule. Or if he already ruled in Suvarnadvipa (an old name for Sumatra). Either way, Balaputra eventually ruled the Sumatran part of the Shailendra dynasty. He became king in the Srivijayan capital of Palembang. Historians think this happened because Balaputra's mother, Tara, was a Srivijayan princess. This made Balaputra the heir to the Srivijayan throne. Balaputra, the Maharaja of Srivijaya, later claimed to be the rightful heir of the Shailendra dynasty from Java. This was stated in the Nalanda inscription from 860 AD.

Between 820 and 850 AD, trade at Canton was disrupted. The ruler of Jambi (Melayu Kingdom) became independent enough to send envoys to China in 853 and 871 AD. Melayu Kingdom's independence happened when Sailendran Balaputradewa was forced out of Java and later took the Srivijayan throne. The new maharaja sent a mission to China by 902 AD. Two years later, the weakening Tang dynasty gave a title to a Srivijayan envoy.

In the early 10th century, there was a lot of trade between the overseas world and the Chinese kingdoms of Min and Nan Han. Srivijaya greatly benefited from this. Around 903 AD, the Muslim writer Ibn Rustah was so impressed by the Srivijayan ruler's wealth. He said no other king was richer, stronger, or had more income. The main cities of Srivijaya were then Palembang, Muara Jambi, and Kedah.

War with Java

In the 10th century, the rivalry between Srivijaya and the Javanese Mataram kingdom grew stronger. This conflict was probably because Srivijaya wanted to get back the Sailendra lands in Java. Or it was because Mataram wanted to challenge Srivijaya's power in the region. In East Java, the Anjukladang inscription from 937 AD mentions an attack from Malayu. This refers to a Srivijayan attack on the Mataram Kingdom of East Java. The people of Anjuk Ladang were rewarded for helping the king's army fight off the invading forces. A victory monument was built in their honor.

In 990 AD, King Dharmawangsa of Java launched a sea invasion against Srivijaya. He tried to capture the capital, Palembang. Chinese Song records mention this Javanese invasion. In 988 AD, a Srivijayan envoy was sent to the Chinese court. After staying in China for about two years, the envoy learned that his country had been attacked by She-po (Java). This made him unable to return home. In 992 AD, an envoy from She-po (Java) arrived in China. He explained that their country was in a continuous war with San-fo-qi (Srivijaya). In 999 AD, the Srivijayan envoy sailed from China to Champa to try to go home. However, he heard no news about his country. The Srivijayan envoy then sailed back to China and asked the Chinese Emperor for protection for Srivijaya against the Javanese invaders.

Dharmawangsa's invasion made the Maharaja of Srivijaya, Sri Cudamani Warmadewa, seek help from China. Warmadewa was known as a smart ruler with good diplomatic skills. During the crisis from the Javanese invasion, he got China's political support by pleasing the Chinese Emperor. In 1003 AD, a Song record said that an envoy from San-fo-qi was sent by King Shi-li-zhu-luo-wu-ni-fo-ma-tiao-hua (Sri Cudamani Warmadewa). The Srivijayan envoy told the Chinese court that a Buddhist temple had been built in their country to pray for the Chinese Emperor's long life. He asked the emperor to name the temple and send a bell for it. The Chinese Emperor was happy. He named the temple Ch'eng-t'en-wan-shou and immediately sent a bell to Srivijaya.

In 1006 AD, Srivijaya's alliance proved strong. They successfully fought off the Javanese invasion. This attack made the Srivijayan Maharaja realize how dangerous the Javanese Mataram Kingdom was. So, he planned to destroy his Javanese enemy. In return, Srivijaya helped Haji (king) Wurawari of Lwaram to revolt. This led to an attack and destruction of the Mataram palace. This sudden attack happened during Dharmawangsa's daughter's wedding. The court was unprepared and shocked. With Dharmawangsa's death and the fall of Mataram's capital, Srivijaya helped cause the collapse of the Mataram kingdom. This left Eastern Java in chaos and violence for several years.

Decline of Srivijaya

Chola Invasion

One reason for Srivijaya's decline was attacks by pirates and foreign raiders. These attacks disrupted trade and safety in the region. Rajendra Chola, the Chola king from Tamil Nadu in South India, launched sea raids on Srivijaya's ports in 1025 AD. His navy quickly sailed to Sumatra using monsoon winds. They made a surprise attack and raided 14 of Srivijaya's ports. The attack caught Srivijaya off guard. They first looted the capital city of Palembang. Then they quickly moved to other ports, including Kadaram (modern Kedah).

The Cholas were known for both piracy and foreign trade. Sometimes, their sea voyages led to outright plunder and conquest as far as Southeast Asia. An inscription of King Rajendra says he captured the King of Kadaram, Sangrama Vijayatunggavarman. He also looted many treasures, including the Vidhyadara-torana, Srivijaya's jeweled 'war gate.'

According to the 15th-century Malay records, Rajendra Chola I married Onang Kiu, the daughter of Vijayottunggavarman, after his successful naval raid in 1025. This invasion forced Srivijaya to make peace with the Javanese kingdom of Kahuripan. The peace deal was arranged by Vijayottunggavarman's exiled daughter. She had escaped the destruction of Palembang and went to the court of King Airlangga in East Java. She became Airlangga's queen, named Dharmaprasadottungadevi. In 1035, Airlangga built a Buddhist monastery called Srivijayasrama for his queen.

The Cholas continued raiding and conquering parts of Sumatra and the Malay Peninsula for the next 20 years. The expedition of Rajendra Chola I left a strong impression on the Malay people. His name is even mentioned (as Raja Chulan) in the medieval Malay chronicle, the Sejarah Melayu (Malay Annals). Even today, Chola rule is remembered in Malaysia. Many Malaysian princes have names ending with Cholan or Chulan.

Rajendra Chola's overseas expeditions against Srivijaya were unique in India's history. India usually had peaceful relations with Southeast Asian states. The reasons for the sea expeditions are not clear. Nilakanta Sastri suggests the attacks were probably because Srivijaya tried to block Chola trade with the East. Or, it might have been Rajendra Chola's simple desire to extend his military victories to well-known countries to gain fame. New research suggests the attack was a pre-emptive strike for trade reasons. Rajendra Chola's naval attack was a smart move for power.

The raids greatly weakened Srivijaya's power. This allowed other regional kingdoms, like Kediri, to form. These kingdoms focused on farming rather than sea trade. Over time, the main trading center shifted from Palembang to Jambi, which was the center of Malayu.

Under Chola Influence

Sanfoqi sent a mission to China in 1028. But this likely referred to Malayu-Jambi, not Srivijaya-Palembang. No Srivijayan envoys went to China between 1028 and 1077. This shows that Srivijaya's power had faded. It's very possible that Srivijaya collapsed in 1025. In the centuries that followed, Chinese records still mentioned "Sanfoqi." But this term probably referred to the Malayu-Jambi kingdom. The last old writing that mentions "Srivijaya" is from the Tanjore inscription of the Chola kingdom in 1030 or 1031.

Chola control over Srivijaya lasted for several decades. Chinese records mentioned Sanfoqi Zhu-nian guo, meaning "Chola country of Sanfoqi." This likely referred to Kedah. Sanfoqi Zhu-nian guo sent missions to China in 1077, 1079, 1082, 1088, and 1090 AD. It's possible that the Cholas put a prince in charge of the Tamil-controlled area of the Malacca Straits.

There is also evidence that Kulottunga Chola, the grandson of Emperor Rajendra Chola I, was in Srivijaya in his youth (1063). He helped restore order and keep Chola influence there. The Cholas left several inscriptions in northern Sumatra and the Malay Peninsula. Tamil influence can be seen in art, like sculptures and temple architecture. This shows government activity rather than just trade. Chola's hold on northern Sumatra and the Malay Peninsula weakened in the 12th century. After that, Kedah disappeared from Indian sources.

Government and Economy

How Srivijaya Was Governed

The 7th-century Telaga Batu inscription shows how complex and organized Srivijaya's government was. It lists many official titles. These include rājaputra (princes), kumārāmātya (ministers), bhūpati (regional rulers), senāpati (generals), nāyaka (local leaders), pratyaya (nobles), hāji pratyaya (lesser kings), dandanayaka (judges), and many others.

When it was formed, the empire had three main areas. These were the capital region around Palembang, the Musi River basin (which provided valuable goods), and rival river areas. These rival areas were brought under Srivijayan power through raids and conquests. Examples include the Batanghari river area (Malayu in Jambi). Several important ports were also included, like Bangka Island, ports in Java, Kedah and Chaiya in the Malay Peninsula, and Lamuri and Pannai in northern Sumatra. There are also reports of Srivijayan attacks on Southern Cambodia and ports of Champa.

After expanding, the Srivijayan empire became a collection of several Kadatuans (local areas). These areas swore loyalty to the main ruling Kadatuan, led by the Srivijayan Maharaja. The political system is described as a mandala model. This was common for classical Southeast Asian Hindu-Buddhist kingdoms. It was like a group of kingdoms or areas under one main power, the central Kadatuan Srivijaya.

The relationship between the central kadatuan and its member kadatuans changed over time. Smaller trading ports were controlled by local rulers who worked for the king. They also collected resources from their regions for export. A part of their income had to be paid to the king. They were not allowed to interfere with international trade. But sometimes, they would secretly trade to keep more money. Some sources say the Champa invasion weakened the central government. This forced the local rulers to keep international trade money for themselves.

Besides using force and loyalty oaths, the royal families often formed alliances through marriages. For example, a smaller area might become more powerful over time. Then its ruler could claim to be the maharaja of the main kadatuan. The relationship between Srivijaya in Sumatra and the Sailendras in Java shows this political change.

Srivijaya's Economy

Trade and Commerce

Srivijaya's main goal in foreign trade was to get good deals for the large Chinese market. This lasted from the Tang dynasty to the Song dynasty. To be part of this trade, Srivijaya sent many envoys to China. They wanted to gain favor with the Chinese court. By 1178, a Srivijayan mission to China showed Srivijaya's role in getting products from Borneo, like camphor.

Srivijaya quickly became a huge empire controlling the two main passages between India and China. These were the Sunda Strait from Palembang and the Malacca Strait from Kedah. Arabic records say the Srivijayan Maharaja's empire was so vast that the fastest ship couldn't travel around all its islands in two years. The islands mentioned produced camphor, aloes, sandal-wood, and spices like cloves, nutmegs, cardamom, and cubebs. They also had ivory, gold, and tin. All these goods made the Maharaja as rich as any king in Medieval India.

River System Model

Besides trade deals, Srivijaya's economy might have used a "riverine system model." This means controlling river systems and river-mouth centers. This ensured the kingdom controlled the flow of goods from inland areas. It also controlled trade in the Malacca Straits and international trade routes. Srivijaya's control of river-mouth centers on the Sumatra, Malaya, and western Java coasts gave Palembang power over the region. They did this through loyalty oaths to local leaders, sharing wealth, and alliances with local chiefs. They didn't use direct force as much.

Goods Traded

Srivijaya's port was an important entrepôt (a place where goods are collected, traded, and shipped). Valuable goods from the region and beyond were traded there. These included Rice, cotton, indigo, and silver from Java. Aloes, resin, camphor, ivory, rhino tusks, tin, and gold came from Sumatra and the Malay Peninsula. Rattan, rare timber, camphor, gems, and precious stones came from Borneo. Exotic birds, rare animals, iron, sappan, sandalwood, and rare spices like clove and nutmeg came from the Eastern Indonesian islands. Chinese ceramics, lacquerware, brocade, fabrics, silks, and artworks were also traded.

What goods were actually from Srivijaya is debated. This is because so many goods passed through the region from India, China, and Arabia. Foreign traders stopped in Srivijaya to trade with other merchants. It was an easy meeting place for traders from different regions. This trade system suggests that Srivijaya's own products might have been less than what old records say. Foreign goods might have piled up in Srivijaya, making it seem like they were from there.

Ceramics were a major trade item between Srivijaya and China. Broken pieces of pottery have been found along the coasts of Sumatra and Java. It's thought that China and Srivijaya might have had a special ceramics trade. This is because certain ceramic pieces are only found in Guangzhou (China) or Indonesia, but nowhere else along the trade route.

The empire used gold and silver coins. They had the image of a sandalwood flower (which Srivijaya controlled) and the word "vara" (glory) in Sanskrit. Other items like porcelain, silk, sugar, iron, rice, and spices could be used for bartering. Some Arabic records say that the king converted trade profits into gold and hid it in a royal pond.

Trade with Arabia

Srivijaya also traded with Arabia. In a likely story, King Sri Indravarman sent a letter to Caliph Umar ibn AbdulAziz in 718 AD. The messenger returned to Srivijaya with a Zanji (a black female slave from Zanj), a gift from the Caliph. Later, a Chinese record mentioned Shih-li-t-'o-pa-mo (Sri Indravarman). It said the Maharaja of Shih-li-fo-shih sent a ts'engchi (Chinese for Zanji) as a gift to the Chinese Emperor in 724 AD.

Arab writers in the 9th and 10th centuries thought the king of Al-Hind (India and parts of Southeast Asia) was one of the world's four great kings. This might have included kings from Sumatra, Java, Burma, and Cambodia. Arab writers always described them as very powerful, with huge armies and vast treasures of gold and silver. Trade records from these centuries mention Srivijaya. But they don't talk about regions further east. This suggests that Arab traders didn't go to other parts of Southeast Asia. This further shows Srivijaya's important role as a link between the two regions.

A Sea-Based Empire?

For some time, Srivijaya controlled the sea trade in the Strait of Malacca. This was part of the Maritime Silk Road. This has led some historians to say that Srivijaya, which controlled many semi-independent port cities, was a Thalassocracy (a sea-based empire). However, the true nature of Srivijaya's navy and sea power is still being studied and debated.

Srivijaya benefited from the profitable sea trade between China and India. It also traded in products like Maluku spices within the Malay Archipelago. As Southeast Asia's main trading hub, Srivijaya constantly managed its trade networks. It was always careful about potential rival ports from nearby kingdoms. Most of the money from international trade was used to pay for the military. The military's job was to protect the ports. Some records even describe using iron chains to prevent pirate attacks.

Srivijayan settlers might have colonized parts of Madagascar. The migration to Madagascar is thought to have happened 1,200 years ago, around 830 AD. A new DNA study suggests that native Malagasy people today might be descended from 30 founding mothers who sailed from Indonesia 1,200 years ago. The Malagasy language has words borrowed from Sanskrit, changed by Javanese or Malay. This hints that Madagascar might have been settled by people from Srivijaya.

Before, people thought Srivijaya was a strong sea power. They believed that a successful state in the Malacca Strait had to be good at international sea activities. But studies show this might not be true. Information about Srivijaya's sea activity is limited. The navy is only mentioned in incomplete sources.

The Kedukan Bukit inscription (683 AD) says that only 312 people used boats out of a total force of 20,000. This force also included 1312 land soldiers. The large number of land troops shows that the Srivijaya navy mainly provided support. In the 8th century, Srivijaya's naval power grew. But it still mostly played a role in logistical support.

Also, there are no specific terms for general or military ships. This suggests the navy was not a permanent part of the state in the Malacca Strait. Even when nearby powers like Java (10th to 14th centuries) and Chola India (11th century) built up their navies, Srivijaya's navy was relatively weak. For example, Chinese records say that between 990 and 991, a Srivijayan envoy couldn't return home because of a war between Java and Srivijaya. However, Javanese, Arab, and South Asian people could still trade with China. This shows that the Javanese navy was strong enough to seriously disrupt Srivijaya's communication with China. The conflict likely happened in rivers and estuaries around Palembang, not on the open sea.

Srivijaya's response to Javanese attacks seemed defensive. A Chinese record from around 1225 AD says: "In the past, [this state] used an iron chain as a barrier to prepare against other robbing parties (arriving on vessels?). There were opportunities to release (i.e. draw) it by hand. If merchant ships arrive, it has to be released."

The states in the Malacca Straits couldn't defend against sea threats in the early 11th century. Between 1017 and 1025, the Cholas raided major Malay ports. They looted the Kedah treasury and captured Srivijayan rulers. This further showed that the states in the Malacca Straits couldn't defend themselves from sea attacks.

So, until the 11th century, Srivijaya was mainly a land-based kingdom in terms of its military. Only after the Chola attacks and more Chinese merchants came to Southeast Asian waters did the role of these navies begin to change.

After the Chola attack, there's little information about naval problems in the Malacca Strait. The Chinese term for Srivijaya, Sanfoqi, was still used. But after 1025, it probably referred to the Malayu Dharmasraya kingdom. New records from 1178 AD say: "This country (Sanfoqi) has no products, but its people are well trained in warfare. When they put medicine on their body, they can't be hurt. In offensive naval warfare, their attacks are unmatched. Therefore, neighboring countries are aligned with it. If foreign ships passing through the vicinity do not call in this state, [vessels] are sent to teach them a lesson and to kill. Therefore, the state is rich..."

Similar information is found in a record from around 1225 AD: "All are excellent in maritime and land warfare... If merchant ships cross [the vicinity] and do not enter [i.e. call at the port], then ships are dispatched to do battle [with them]. They have to die (i.e. the persons onboard the merchant ships have to be killed). Hence, this state (Sanfoqi) is a great shipping centre."

These records suggest that sea and river warfare became very different in the late 12th and 13th centuries. The navy's role in the government's survival also changed.

At the same time, the 12th century saw the decline of empires around the Malacca Straits. Kedah fell out of Sanfoqi's influence in the 11th century. By the early 13th century, other areas had direct trade with China. Jambi became independent from Sanfoqi in the early 13th century.

After Singhasari attacked Malayu in 1275, many Malay port-states appeared. Each tried to trade directly with foreign merchants. So, developing a more active navy was a response to changing trade and the declining power of these states.

Srivijayan Explorers

Srivijaya's main area was in and around the Malacca and Sunda straits, and in Sumatra, the Malay Peninsula, and Western Java. But between the 9th and 12th centuries, Srivijaya's influence seemed to spread far beyond this core. Srivijayan sailors may have reached as far as Madagascar. The migration to Madagascar is thought to have happened around 830 AD. The Malagasy language has words borrowed from Sanskrit, through Javanese or Malay. This suggests that Madagascar might have been settled by people from Srivijaya.

Culture and Society

Srivijaya-Palembang was important for trade and for practicing Vajrayana Buddhism. This is known from Arab and Chinese historical records. Srivijaya's own historical writings, in Old Malay, are mostly from the second half of the 7th century. These writings show a system where the king was served by many high-ranking officials. Srivijayan society was complex, diverse, and wealthy. It had refined tastes in art, literature, and culture. It had complex rituals influenced by Mahayana Buddhist faith. Their social order can be seen in the writings, foreign accounts, and temple carvings from that time. Their artistic skill is shown by the many Srivijayan Art Mahayana Buddhist statues found in the region. The kingdom had a complex society with different social levels and a national government. They used metal for jewelry, coins, and status symbols.

Art and Culture

Trade helped art spread. Some art was heavily influenced by Buddhism. This helped spread religion and ideas through art trade. The Buddhist art and buildings of Srivijaya were influenced by Indian art from the Gupta Empire and Pala Empire. This is clear from the Indian Amaravati style Buddha statue in Palembang. This statue, from the 7th and 8th centuries, shows how art, culture, and ideas spread through trade.

Old records say that Srivijaya's capital had a complex and diverse society with a refined culture. It was deeply influenced by Vajrayana Buddhism. The 7th-century Talang Tuwo inscription describes Buddhist rituals and blessings for creating a public park. This writing helps historians understand the practices and their importance in Srivijayan society. Talang Tuwo is one of the world's oldest writings about the environment. It shows how important nature was in Buddhist religion and Srivijayan society. The Kota Kapur Inscription mentions Srivijaya's military power against Java. These writings were in the Old Malay language. This was the language used by Srivijaya and is the ancestor of modern Malay and Indonesian language.

Since the 7th century, Old Malay has been used in Nusantara (the Malay Archipelago). This is shown by Srivijayan writings and other old Malay writings found in coastal areas. Traders helped spread the Malay language because it was used among them. Soon, Malay became a common language spoken by most people in the archipelago.

However, despite its economic, cultural, and military strength, Srivijaya left few old buildings in Sumatra. This is unlike the Sailendras of Central Java, who built many monuments like Kalasan, Sewu, and Borobudur. The Buddhist temples from Srivijaya in Sumatra are Muaro Jambi, Muara Takus, and Biaro Bahal.

Some Buddhist sculptures, like Buddha Vairocana, Boddhisattva Avalokiteshvara, and Maitreya, were found in many places in Sumatra and the Malay Peninsula. These include a stone Buddha statue from Bukit Seguntang, Palembang. Also, Avalokiteshvara from Bingin Jungut in Musi Rawas, and a bronze Maitreya statue from Komering, all in South Sumatra. In Jambi, a golden Avalokiteshvara statue was found in Rataukapastuo. In the Malay Peninsula, a bronze Avalokiteshvara statue was found in Bidor, Malaysia, and another in Chaiya, Southern Thailand. The different materials but common Buddhist theme show how Buddhism spread through trade.

After the Bronze and Iron Ages, many bronze tools and jewelry spread throughout the region. Different styles of bracelets and beads show where they came from. Chinese artworks were a main trade item, spreading art styles in ceramics, pottery, fabrics, and silks.

Religion in Srivijaya

Remains of Buddhist shrines (stupas) near Palembang help us understand Buddhism in this society. Srivijaya and its kings were important in spreading Buddhism. They established it in places they conquered, like Java, Malaya, and other lands. People on pilgrimages were encouraged to spend time with monks in the capital city of Palembang on their way to India.

Besides Palembang, three other Buddhist sites are notable in Srivijaya's Sumatra. These are Muaro Jambi by the Batang Hari River in Jambi province. Also, Muara Takus stupas in the Kampar River valley of Riau province. And Biaro Bahal temple compound in the Barumun and Pannai river valleys, North Sumatra province. These Buddhist sites were likely sangha communities. They were Buddhist learning centers that attracted students and scholars from all over Asia.

In the 5th century AD, the Chinese monk Faxian visited the region. 250 years later, the monk Yijing stayed in Srivijaya for six months and studied Sanskrit. Yijing said that in Palembang, there were over 1000 monks studying and training traveling scholars. These travelers were going from India to China and vice versa. They often stayed in Palembang for long periods, waiting for monsoon winds to help their journey.

Srivijaya was a strong center of Vajrayana Buddhism. It attracted pilgrims and scholars from other parts of Asia. These included the Chinese monk Yijing. He visited Sumatra many times on his way to study at Nalanda University in India in 671 and 695 AD. The 11th-century Bengali Buddhist scholar Atisha also played a big role in developing Vajrayana Buddhism in Tibet. Yijing and other monks practiced a pure form of Buddhism. He is also credited with translating Buddhist texts that have many rules for the religion. I Ching reported that the kingdom had over a thousand Buddhist scholars. He wrote his memoir about Buddhism in Srivijaya. Travelers to these islands said that gold coins were used in coastal areas but not inland. Srivijaya attracted priests from as far away as Korea.

A notable Srivijayan Buddhist scholar was Dharmakirti. He taught Buddhist philosophy in Srivijaya and Nalanda. The language in many writings found near Srivijaya included Indian Tantric ideas. This shows the connection between the ruler and the idea of a bodhisattva (someone who will become a Buddha). This is the first time we see evidence of a Southeast Asian ruler being seen as a religious leader.

One thing researchers have noticed is that Srivijaya didn't focus much on art and architecture. While nearby regions have complex buildings, like the Borobudur temple built under the Sailendra dynasty, Palembang has few Buddhist stupas or sculptures.

Besides Buddhism, Hinduism was also practiced in the Srivijayan kingdom. This is known from the discovery of the Bumiayu temple ruins. This was a red brick Shivaist Hindu temple complex built and used between the 8th and 13th centuries AD. The Bumiayu temple site is on the banks of the Lematang River, a branch of the Musi River. This temple complex was probably built by a local area within Srivijaya's influence. The fact that a Hindu temple was found in the area of the Srivijayan Buddhist empire suggests that both Hinduism and Buddhism existed peacefully among the people.

The styles of Shiva and Agastya statues found in Bumiayu temple 1 date from around the 9th to 10th centuries. By the 12th to 13th centuries, it seems that the religion in Bumiayu shifted from Hinduism to Tantric Buddhism.

Srivijaya's Connections with Other Powers

Even though old records and archaeological evidence are few, it seems that by the 7th century, Srivijaya controlled large parts of Sumatra, western Java, and much of the Malay Peninsula. At first, Srivijaya controlled a group of semi-independent port cities. It did this by forming alliances and gaining loyalty from these areas. As the main port in the region, Srivijaya had a special "ritual policy" in its relations with powerful areas in South Asia, Southeast Asia, and especially China.

The oldest accounts of the empire come from Arab and Chinese traders. They wrote about the empire's importance in regional trade. Its location was key to becoming a major connecting port between China, the Middle East, and Southeast Asia. Controlling the Malacca and Sunda Straits meant it controlled both the spice route traffic and local trade. It charged a toll on passing ships. Palembang, a port accessible by river, became very wealthy. Instead of traveling the whole distance from the Middle East to China, which took about a year, it was easier to stop in Srivijaya. It took about half a year from either direction to reach Srivijaya. This was much more efficient. This idea is supported by evidence from two shipwrecks. One was off the coast of Belitung, an island east of Sumatra. The other was near Cirebon, a coastal city on Java. Both ships carried various foreign goods.

The Melayu Kingdom was the first rival power to be absorbed into the empire. This began Srivijaya's control of the region through trade and conquest from the 7th to 9th centuries. The Melayu Kingdom's gold mines in the Batang Hari River area were a vital economic resource. They might be the origin of the word Suvarnadvipa, the Sanskrit name for Sumatra. Srivijaya helped spread Malay culture throughout Sumatra, the Malay Peninsula, and western Borneo. Its influence lessened in the 11th century.

According to Sung-shih, a Song dynasty record, Srivijaya sent its envoys for the last time in 1178. Then in 1225, Chau Ju-kua mentioned that Palembang (Srivijaya) was a vassal kingdom of Sanfotsi. This means that between 1178 and 1225, the Srivijaya kingdom in Palembang was defeated by the Malayu kingdom in Jambi. So, the empire's center moved to Muaro Jambi in its last centuries.

Srivijaya often fought with, and was eventually taken over by, the Javanese kingdoms of Singhasari and later, Majapahit. This wasn't the first conflict with the Javanese. Historian Paul Michel Munoz says the Javanese Sanjaya dynasty was a strong rival of Srivijaya in the 8th century.

The Khmer Empire might have been a tributary state (paying tribute) in its early days. The Khmer king, Jayavarman II, spent years in the Sailendra court in Java. He returned to Cambodia to rule around 790 AD. Influenced by the Javanese culture, he declared Cambodian independence from Java. He ruled as devaraja (god-king), starting the Khmer empire and the Angkor era.

Some historians claim that Chaiya in Surat Thani Province in southern Thailand was, at least for a time, Srivijaya's capital. But this is widely debated. However, Chaiya was probably an important regional center of the kingdom.

Srivijaya also had close ties with the Pala Empire in Bengal. The Nalanda inscription, dated 860, records that Maharaja Balaputra built a monastery at the Nalanda university in Pala territory. The relationship between Srivijaya and the Chola dynasty of southern India was friendly at first. In 1006, a Srivijayan Maharaja, King Maravijayattungavarman, built the Chudamani Vihara in the port town of Nagapattinam. However, during the rule of Rajendra Chola I, the relationship worsened as the Chola dynasty began to attack Srivijayan cities.

The reason for this sudden change is not fully known. Some historians suggest that the Khmer king, Suryavarman I, asked Emperor Rajendra Chola I for help against Tambralinga. After learning of this alliance, the Tambralinga kingdom asked the Srivijaya king, Sangrama Vijayatungavarman, for help. This led to the Chola Empire fighting the Srivijaya Empire. The conflict ended with a Chola victory. Srivijaya suffered heavy losses, and Sangramavijayottungavarman was captured in the Chola raid in 1025. During the reign of Kulothunga Chola I, Srivijaya sent an embassy to the Chola dynasty.

Srivijaya's Lasting Impact

Even though Srivijaya left few old buildings and was almost forgotten, its rediscovery by Cœdès in the 1920s showed that a large political power could have existed in Southeast Asia long ago. Modern Indonesian historians see Srivijaya as a source of pride and an example of how ancient globalization, foreign relations, and sea trade shaped Asian civilization.

Perhaps the most important legacy of the Srivijayan empire was its language. Unlike some other kingdoms of its time, which used Sanskrit, Srivijayan writings were in Old Malay. This raised the status of local languages compared to Sanskrit. Sanskrit was only known by a few people, like priests and poets. But Old Malay was a common language in Srivijaya. This language policy probably came from the more equal nature of Mahayana Buddhism in Srivijaya, unlike the strict social classes of Hinduism. For centuries, Srivijaya, through its growth, economic power, and military strength, helped spread Old Malay throughout the Malay Archipelago. It was the language used by traders in various ports and markets. The language of Srivijaya likely led to the importance of today's Malay and Indonesian language. These are now official languages in Brunei, Malaysia, and Singapore, and the unifying language of modern Indonesia.

Today, in Indonesian art, the songket weaving art is strongly linked to Palembang. This has led historians to look for the origin of songket and its possible link to Srivijaya. Studies of the Bumiayu temple complex in South Sumatra show that songket was known there since the 9th century AD. A fabric pattern known today as lepus in Palembang songket can be seen on a statue from the Bumiayu temple complex. This shows that the pattern has been around since the 9th century. This study suggests that the tradition of weaving with gold threads is a heritage from the Srivijaya empire.

Modern Indonesian thinkers also use the name Srivijaya, along with Majapahit, as a source of pride in Indonesia's past greatness. Srivijaya has become a focus of national pride and local identity, especially for the people of Palembang and South Sumatra province. For the people of Palembang, Srivijaya has also inspired the Gending Sriwijaya song and traditional dance.

In Indonesia, Srivijaya is a street name in many cities. It is now linked with Palembang and South Sumatra. Srivijaya University, founded in 1960 in Palembang, was named after Srivijaya. Other things named after this ancient empire include Kodam Sriwijaya (a military unit), PT Pupuk Sriwijaya (a fertilizer company), Sriwijaya Post (a newspaper), Sriwijaya Air (an airline), Gelora Sriwijaya Stadium, and Sriwijaya F.C. (a football club). On November 11, 2011, during the opening ceremony of the 2011 Southeast Asian Games in Gelora Sriwijaya Stadium, a huge dance performance called "Srivijaya the Golden Peninsula" was held. It featured traditional Palembang dances and a life-sized replica of an ancient ship to show the empire's glory. In popular culture, Srivijaya has inspired many fictional films, novels, and comic books. For example, the 2013 film Gending Sriwijaya takes place three centuries after Srivijaya fell. It tells a story about court drama and efforts to bring back the fallen empire.

Kings of Srivijaya

| Date | Name | Capital | Important Events and Records |

|---|---|---|---|

| 683 | Dapunta Hyang Sri Jayanasa | Srivijaya | Kedukan Bukit Inscription (683), Talang Tuwo inscription (684), and Kota Kapur Inscription (686) writings.

Conquered Malayu, expedition to Java (results unknown). |

| 702 | Sri Indravarman | Srivijaya | Sent envoys to China in 702, 716, 724.

Sent envoys to Caliph Muawiyah I and Caliph Umar bin Abdul Aziz. |

| 728 | Rudra Vikrama | Srivijaya | Sent envoys to China in 728, 742. |

| No information for the period 742–775 | |||

| 775 | Dharmasetu or Vishnu | Unknown (under Javanese Sailendra dynasty's influence) | Nakhon Si Thammarat (Ligor), Vat Sema Muang. |

| 775 | Dharanindra | Unknown (under Javanese Sailendra dynasty's influence) | Ligor, started building Borobudur in 770,

conquered South Cambodia. |

| 782 | Samaragrawira | Unknown (under Javanese Sailendra dynasty's influence) | Ligor, mentioned in Arabian texts (790), continued building Borobudur. |

| 792 | Samaratungga | Unknown (under Javanese Sailendra dynasty's influence) | Karangtengah inscription (824), lost Cambodia in 802, completed Borobudur in 825. |

| 835 | Balaputradewa | Srivijaya | Forced out of Java.

Nalanda inscription (860). |

| No information for the period 835–960 | |||

| 960 | Sri Udayadityavarman | Srivijaya | Sent envoys to China in 960, 962. |

| 980 | Haji | Srivijaya | Sent envoys to China in 980, 983. |

| 988 | Sri Cudamani Warmadewa | Srivijaya | Sent envoys to China in 988, 992, 1003, 1004.

Javanese King Dharmawangsa attacked Srivijaya, built a temple for the Chinese Emperor, mentioned in Tanjore Inscription (1044), built a temple at Nagapattinam with money from Rajaraja Chola I. |

| 1006, 1008 | Sri Maravijayottungavarman | Srivijaya | Built the Chudamani Vihara in Nagapattinam, India in 1006.

Sent envoys to China in 1008, 1016. |

| 1017 | Sumatrabhumi | Srivijaya | Sent envoy to China in 1017. |

| 1025 | Sangrama Vijayatunggavarman | Srivijaya | Chola invasion of Srivijaya, captured by Rajendra Chola.

Mentioned in Chola Inscription on the temple of Rajaraja, Tanjore. |

| 1028 | Sri Deva | Palembang | Sent envoy to China in 1028.

Built Tien Ching temple for the Chinese Emperor. |

| 1045 | Samara Vijayatunggavarman | Srivijaya | Madigiriya inscription, Bolanda inscription. |

| 1078 | Kulothunga Chola I | Unknown (under Chola dynasty's influence) | Sent envoy to China in 1077. |

Images for kids

-

An ancient Javanese ship shown on the Borobudur temple.

See also

In Spanish: Srivijaya para niños

In Spanish: Srivijaya para niños