Mataram Kingdom facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Mataram Kingdom

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 716–1016 | |||||||||

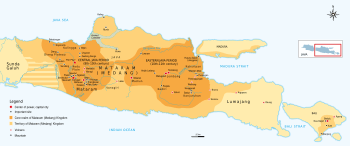

The Mataram Kingdom during the Central Java and Eastern Java periods

|

|||||||||

| Capital | Mamratipura Poh Pitu Tamwlang Watugaluh |

||||||||

| Common languages | Old Javanese, Sanskrit | ||||||||

| Religion | Hinduism, Buddhism, Animism | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

| Maharaja | |||||||||

|

• 716–746 (first)

|

Sanjaya | ||||||||

|

• 985–1016 (last)

|

Dharmawangsa | ||||||||

| Historical era | Medieval Southeast Asia | ||||||||

|

• Sanjaya ascends the throne (Sanjayawarsa)

|

716 | ||||||||

|

• Dharmawangsa defeat to Wurawari and Srivijaya

|

1016 | ||||||||

| Currency | Masa and Tahil (native gold and silver coins) | ||||||||

|

|||||||||

The Mataram Kingdom (Javanese: ꦩꦠꦫꦩ꧀) was an old Javanese kingdom. It was a mix of Hindu and Buddhist beliefs. This kingdom was very important from the 8th to the 11th centuries. It started in Central Java and later moved to East Java.

King Sanjaya founded the kingdom. It was ruled by two main families: the Shailendra dynasty and the Ishana dynasty. People in Mataram mostly grew rice. Later, they also became good at trading by sea.

Foreign visitors and old discoveries show that Mataram was a rich and busy place. The kingdom had a well-organized society and a rich culture. They built many amazing temples.

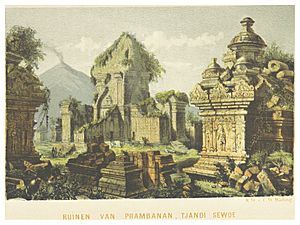

Between the late 700s and mid-800s, Mataram became famous for its art and buildings. Many temples were built in the heart of Mataram. Some of the most famous ones are Kalasan, Sewu, Borobudur, and Prambanan. These are all near the city of Yogyakarta today.

At its strongest, Mataram was a powerful empire. It controlled not only Java but also parts of Sumatra, Bali, southern Thailand, and even kingdoms in the Philippines and Cambodia.

Later, the ruling families split based on their religion. There was a Buddhist family and a Shivaist (Hindu) family. This led to a civil war. The Mataram kingdom then divided into two strong parts. The Hindu part stayed in Java, led by Rakai Pikatan. The Buddhist part joined the Srivijaya kingdom in Sumatra, led by Balaputradewa.

These two kingdoms remained enemies. In 1016, the Srivijaya family helped a local ruler named Wurawari. Wurawari attacked Mataram's capital in East Java. This attack destroyed the capital. Srivijaya then became the most powerful empire in the region. However, the Hindu family of Mataram survived. They took back East Java in 1019. Then, they started the Kahuripan kingdom under Airlangga. He was the son of Udayana Warmadewa from Bali.

Contents

- Discovering Ancient Mataram

- What's in a Name?

- History of the Mataram Kingdom

- The Ruling Families

- Government and Daily Life

- Culture and Society

- Mataram's Neighbors

- Mataram's Lasting Impact

- List of Mataram Rulers

- See also

Discovering Ancient Mataram

In the early 1800s, people found many ruins of huge temples. These included Borobudur, Sewu, and Prambanan. They were found in the Kedu and Kewu plains in Yogyakarta and Central Java. These discoveries made historians curious. They started digging to learn about this old civilization.

The Mataram area was the capital of the Central Javanese Mataram kingdom. This area is part of the historical land of Java. People from India called it Yawadvipa. The Khmer called it Chvea. The Chinese knew it as Shepo or Chao-wa. Arabs called it Jawi or Zabag. The native Javanese usually called their land Jawi (Java). The name of their country often came from its capital city.

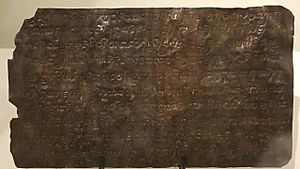

We don't have many old written records from Java. Most of what we know comes from prasasti (inscriptions). These are writings on stones or copper plates. They often tell about the rulers' political and religious actions. Many inscriptions talk about setting up Sima lands. These were special rice farms where taxes were used to build and maintain temples.

Some local stories and old writings on lontar (palm leaves) also help us. These often come from later times. They still give us clues about historical events.

Old Javanese mythology from the 1600s mentions a kingdom called Medang Kamulan. This name means "Medang the origin" kingdom. This might be a memory of the ancient "Medang" kingdom.

Today, we learn about ancient Javanese civilization from:

- Archaeological digs: Finding and studying old buildings like temples (candi). Also, discovering old treasures like the Wonoboyo hoard.

- Stone inscriptions: These tell about kings, their families, and temple funding. Important ones are Canggal, Kalasan, Shivagrha, and Balitung charter.

- Bas reliefs: Carvings on temple walls that show daily life. They show palaces, villages, markets, and people. Famous ones are on Borobudur and Prambanan.

- Native manuscripts: Stories about kings that match information from inscriptions. An example is the Carita Parahyangan.

- Foreign reports: Writings from Chinese, Indian, and Arab travelers and traders.

What's in a Name?

The name Mataram comes from the Sanskrit word mātaram. It means "mother" or "motherland." Old writings call it kaḍatwan śrī mahārāja i bhūmi i mātaram. This means "Maharaja's kingdom in Mataram." It shows Mataram as a mother figure, symbolizing life and nature.

The name Mataram Kingdom was first known during the time of King Sanjaya. An inscription from 732 AD, called the Canggal inscription, mentions him ruling Java. Later, in 880 AD, the Wuatan Tija inscription clearly uses the name "Mataram Kingdom." Other inscriptions mention places like Mamratipura and Poh Pitu as government centers in Central Java.

The name Medang also appeared in inscriptions. It showed that the Medang palace was in the Mataram Kingdom. "Medang" might come from the name of a local hardwood tree.

Even when the kingdom moved to East Java, the name Mataram was still used. For example, in 929 AD, the Turyan inscription mentions the capital in Tamwlang. Later, in 943 AD, the Paradah inscription says the capital moved to Watugaluh. Even in 995 AD, the Wwahan inscription still calls the kingdom "Mataram." This shows the name stayed even after the capital moved.

The name "Mataram" was used for this Hindu-Buddhist kingdom in the 8th century. It appeared again in the 16th century for an Islamic kingdom, the Mataram Sultanate. So, historians call this older kingdom "Ancient Mataram" to avoid confusion.

This ancient Javanese Mataram Kingdom is not the same as the Mataram city on Lombok island. That city was named by Balinese nobles in the 1800s. They often named their new places after their Javanese heritage.

History of the Mataram Kingdom

How Mataram Began and Grew

The earliest record of the Mataram Kingdom is the Canggal inscription. It dates back to 732 AD. This inscription was found near the Gunung Wukir temple in Canggal village. It tells how King Sanjaya set up a special stone (a symbol of the god Shiva) on a hill in Java. The inscription says Java was a rich island with lots of rice and gold.

Before Sanjaya, King Sanna ruled Java wisely. After Sanna died, the kingdom faced problems. Sanjaya, Sanna's nephew, became king. He took control of nearby areas. His rule brought peace and wealth to his people.

Sanjaya likely became king around 717 CE. This year marks the start of his rule. He started a new kingdom in Southern Central Java. But it seems to have continued from King Sanna's earlier kingdom. This older kingdom is linked to the temples in Dieng Plateau. These are the oldest buildings in Central Java. The kingdom before Mataram was likely Kalingga, located on Java's northern coast.

The story of Sanna and Sanjaya also appears in the Carita Parahyangan. This book was written much later, around the late 1500s. It mainly tells the history of the Sunda Kingdom. In this book, Sanjaya is Sanna's son. It says Sanna was defeated by King Purbasora of Galuh. Sanjaya then attacked Galuh to get revenge. He killed Purbasora and took back his father's kingdom. He ruled West Java, Central Java, East Java, and Bali. He also fought against the Malayu and Keling kingdoms. Even though this story might be romanticized, it seems to be based on real events.

The Golden Age of Mataram

The time from King Panangkaran to King Balitung (around 760 to 910 AD) was Mataram's golden age. This period lasted about 150 years. Javanese art and buildings flourished. Many grand temples and monuments were built. They filled the Kedu and Kewu Plain areas. The most famous temples are Sewu, Borobudur, and Prambanan. The Shailendra kings were known for building many temples.

King Sanjaya was a Hindu (Shivaist). But his successor, Panangkaran, was a Buddhist. This change in religion has puzzled historians. Some think there were two royal families, one Hindu and one Buddhist. Others believe there was only one family, the Shailendras. They think the royal family simply changed its main religion over time.

The Great Builders

Panangkaran (ruled 760–780 AD) was a very active builder. He started at least five major temple projects. The Kalasan inscription from 778 AD says that Kalasan temple was built for the goddess Tara. It was built at the request of a Buddhist teacher. Panangkaran also built a vihara (monastery) for Buddhist monks. He gave the village of Kalaça to the Buddhist community (sangha). Kalasan temple holds the image of Tara. The nearby Sari temple was probably the monastery.

Panangkaran also started building Abhayagiri Vihara, now known as Ratu Boko. This hilltop site was not just a religious place. It had gates, walls, and terraces. It might have been a fortified palace or a citadel. It was probably first a quiet Buddhist monastery. But later, it seems to have become a strong palace.

King Panangkaran likely also planned the huge Manjusrigrha temple. An inscription from 792 AD mentions it. But the king died before this grand temple complex was finished. It was completed in 792 AD, long after his death. This massive complex had 249 buildings. It was probably the kingdom's main temple for important ceremonies.

The Great Conquerors

Some records say Javanese ships attacked Tran-nam in 767 AD, and Champa in 774 and 787 AD. Panangkaran's successor was Dharanindra (ruled 780–800 AD), also known as King Indra. The Kelurak inscription (782 AD) calls him Wairiwarawiramardana, meaning "the slayer of brave enemies." A similar title is found in the Ligor B inscription in Southern Thailand. This suggests he was a strong warrior. He led naval expeditions overseas and brought Ligor under Shailendra control.

King Indra also continued building temples. He kept working on the Manjusrigrha temple (Sewu complex). The Karangtengah inscription (824 AD) says he built the Venuvana temple, which might be Mendut or Ngawen temple. He also likely started the building of Borobudur and Pawon temple.

Dharanindra became the Maharaja of Srivijaya. The connection between the Shailendra family in Java and the Srivijaya empire in Sumatra is complex. It seems that at first, the Shailendra family was under Srivijaya's influence. Later, the Shailendra kings became the main rulers of Srivijaya. It's not clear how this shift happened. It might have been through military campaigns or a strong alliance between the families.

Inscriptions like the Ligor inscription, Laguna Copperplate Inscription, and Pucangan inscription show Mataram's influence. It reached as far as Bali, southern Thailand, the Philippine islands, and the Khmer in Cambodia. In 851 AD, an Arab merchant named Sulaimaan wrote about Javanese Sailendras attacking the Khmers. They came by river after sailing from Java. The young Khmer king was punished, and his kingdom became a vassal of the Sailendra dynasty. In 916 CE, a Javanese kingdom invaded the Khmer Empire with 1000 ships. The Javanese won, and the Khmer king's head was brought to Java.

The Peaceful Ruler

Dharanindra's successor was Samaragrawira (ruled 800–819 AD). The Nalanda inscription (860 AD) says he was the father of Balaputradewa. He was also the son of Dharanindra. Unlike his father, Samaragrawira seemed peaceful. He enjoyed the wealth of Java and focused on finishing the Borobudur project. He made the Khmer prince Jayavarman the governor of Indrapura in Cambodia. This was a mistake, as Jayavarman later rebelled. He moved his capital and declared Cambodian independence from Java in 802 AD. Samaragrawira was also known as Rakai Warak in the Mantyasih inscription.

Some older historians thought Samaragrawira and Samaratungga were the same person. But later historians believe Samaratungga was Rakai Garung. He is mentioned as the fifth king of Mataram in the Mantyasih inscription. This means Samaratungga was Samaragrawira's successor.

Samaratungga (ruled 819–838 AD) is credited with finishing the massive Borobudur monument in 825 AD. Like Samaragrawira, Samaratungga was deeply influenced by peaceful Buddhist beliefs. He tried to be a kind and peaceful ruler. His successor was Princess Pramodhawardhani. She married the Hindu (Shivaite) Rakai Pikatan. He was the son of an important landlord in Central Java. This marriage was likely a political move to bring peace. It aimed to unite the Buddhist and Hindu groups and secure Shailendra rule in Java.

The rule of the Hindu Rakai Pikatan (ruled 838–850 AD) and his Buddhist queen Pramodhawardhani marked a shift. The Mataram court started to favor Hindu beliefs again. This is clear from the building of the grand Shivagrha temple complex. It was very close to the Manjusrigrha temple. However, relations between the religions seemed tolerant during Pikatan's rule. They built and expanded parts of the Plaosan temple complex. Plaosan temple might have been started earlier but was finished during Pikatan and Pramodhawardhani's time.

The Kingdom Divides

Balaputra did not agree with Pikatan and Pramodhawardhani's rule. Historians have different ideas about Balaputra's relationship with Pramodhawardhani. Some say he was her younger brother. Others say he was her uncle.

It's not known if Balaputra was forced out of Central Java because of a fight over who would be king. Or if he already ruled in Suvarnadvipa (Sumatra). Either way, Balaputra eventually ruled the Sumatran branch of the Shailendra dynasty. He became king in Srivijaya's capital, Palembang. Historians think this happened because Balaputra's mother, Tara, was a Srivijayan princess. This made Balaputra an heir to the Srivijayan throne. Balaputra later claimed to be the rightful heir of the Shailendra dynasty from Java. This was stated in the Nalanda inscription from 860 AD.

The Shivagrha inscription (856 AD) mentions a war against Pikatan's rule. But it doesn't say who the enemy was. Earlier historians thought it was Balaputradewa. But later historians think it was another enemy, as Balaputra was likely already in Srivijaya. The inscription only says the battle happened at a fortress on a hill. This hill is believed to be the Ratu Boko archaeological site. Pikatan's youngest son, Dyah Lokapala, also known as Rakai Kayuwangi, defeated the revolt. Because of his bravery, he was chosen as the crown prince instead of his older sibling, Gurunwangi.

This revolt might have taken over the capital in Mataram for a while. After winning, Pikatan felt the capital was unlucky because of the bloodshed. So, he moved the karaton (court) to Mamrati or Amrati. This place was in the Kedu Plain, northwest of Mataram.

Later, Pikatan gave his throne to his youngest son, Dyah Lokapala (ruled 850–890 AD). Rakai Pikatan retired and became a hermit named Sang Prabhu Jatiningrat. This event also included a ceremony for a Shiva statue in the main Prambanan temple. Some historians think the enemy was Rakai Walaing pu Kumbhayoni. He was a powerful Hindu landlord and part of the ruling family.

A Short Period of Peace

The Mataram kings after Pikatan—Lokapala, Watuhumalang (ruled 890–898 AD), and Balitung—were Hindu (Shivaist). Their rule seemed to be peaceful. The grand Shivagrha temple complex continued to grow. Hundreds of smaller temples surrounded the three main towers dedicated to Hindu gods. During their time, other Hindu temples like Sambisari, Barong, Ijo, and Merak temple were likely built. Barong and Ijo temples are interesting because they were built on hills. Their layout was different from earlier temples like Sewu and Prambanan. This new style likely influenced later East Javanese temples.

Kings Pikatan, Lokapala, and Watuhumalang ruled from Mamrati or Amrati. They were known as "Amrati Kings." We don't know the exact location of Mamrati. It was likely in the Kedu Plain (modern Magelang and Temanggung areas). Some think Amrati might be near the Wanua Tengah III inscription.

The name "Mataram" reappeared during Balitung's rule. This might mean the capital moved again. King Balitung moved his capital from Amrati to Poh Pitu. He renamed Poh Pitu to Yawapura. Its exact location is also unknown, but it was probably in the Kedu Plain. Balitung issued many inscriptions. These include Telahap (899), Watukura (902), Telang (904), Poh (905), Kubu-Kubu (905), Mantyasih (907), and Rukam (907).

The Mantyasih inscription (907 AD) is very important. It lists the kings of Mataram, starting from King Sanjaya. This inscription, known as "Balitung charter," helped us learn the names of the rulers. Balitung might have issued it to show his right to rule. He was likely related to the royal family, perhaps by marrying the previous king's daughter.

The Watukura inscription (902 AD) is the oldest to mention the position of Prime Minister. During Balitung's time, the position of Crown Prince was held by Mpu Daksa. The relationship between Balitung and Daksha is unclear. Daksha might have been the son of the previous king (Watuhumalang). Historians think Daksha's rebellion ended Balitung's rule.

The Telang inscription (904 AD) talks about the port of Paparahuan on the Bengawan Solo river. Building this port shows a growing interest in sea trade. This might mean the court's focus was shifting eastward.

The Kubu-Kubu inscription (905 AD) says Kubu-kubu village was given to two officials. This was for their bravery in conquering Bantan. Bantan's location is not clear. It might be Banten Girang in West Java, or even Bali. In old Javanese, Bantan means sacrifice, similar to Bali meaning offering.

The Mantyasih inscription (907 AD) also mentions gifts given to officials. This was for keeping peace during Balitung's wedding. In the Rukam inscription (907 AD), Balitung said taxes from Rukam village would fund a temple. This temple was for his grandmother, Nini Haji Rakryan Sanjiwana. This is likely the Sajiwan Buddhist temple near Prambanan. It was probably finished during Balitung's reign. It might have been a special temple for the deceased queen mother, Pramodhawardhani.

The rivalry between Balitung and Daksha might have come from an earlier fight over who would be king. After Balitung, the building of grand temples became less common.

King Daksha (ruled 910–919 AD) and his successor King Tulodong (ruled 919–924 AD) also ruled from Poh Pitu. The next king, Wawa (ruled 924–929 AD), moved the capital back to Mataram. The Sanggurah inscription (928 AD) found in Malang, East Java, is interesting. It says King Wawa gave special status to land near the Brantas river. This means that during Wawa's rule, the kingdom had expanded eastward. They set up new areas along the Bengawan Solo and Brantas rivers.

Overseas Connections

An Arab record from the 10th century, Ajayeb al-Hind, tells about an invasion in Africa. It was by people called Wakwak or Waqwaq. These were likely Malay people from Srivijaya or Javanese people from Mataram. In 945-946 CE, they arrived in Tanganyika and Mozambique with 1000 boats. They tried to take a fort but failed. They wanted goods like ivory and ambergris. They also wanted strong black slaves from Bantu people (called Zeng or Zenj).

Inscriptions from 931 AD and 1053 AD show that Mataram and later the Airlangga's era Kahuripan kingdom were very rich. They needed many workers to carry crops and send them to ports. Black workers were brought from Jenggi (Zanzibar), Pujut (Australia), and Bondan (Papua). They came to Java through trade or as war prisoners.

Moving Eastward

Around 929 AD, the center of the kingdom moved from Central Java to East Java. Mpu Sindok made this move and started the Isyana Dynasty. The exact reason for this move is not fully known. Historians have suggested several reasons: natural disasters, diseases, political fights, or economic reasons.

One idea, supported by Professor Boechari, is that a big eruption of Mount Merapi volcano caused the move. During King Wawa of Mataram's rule (924—929 AD), Merapi might have erupted. This event is known as Pralaya Mataram (the disaster of Mataram). Evidence for this is that several temples, like Sambisari and Kedulan, were buried under volcanic mud and ash.

Archaeologist Agus Aris Munandar thinks the move was for religious reasons. He says Merapi was seen as the sacred Mount Meru in ancient Javanese beliefs. Since their sacred mountain kept erupting, they moved. They looked for another sacred mountain, possibly Mount Penanggungan in East Java.

Another idea is that a disease outbreak forced people to find a new home. Or, it could have been economic reasons. The many temples built by the Shailendra kings might have put a huge financial burden on the farmers. People might have moved east to escape these demands.

A power struggle is also a possible reason. Some historians suggest the move was to avoid an invasion from Srivijaya in Sumatra.

However, economic reasons are also very likely. The Brantas river valley in East Java was a good location. The river provided easy access to ports on the north coast and the Java Sea. This was important for controlling sea trade routes, especially for the Maluku spice trade. Central Java's Kedu and Kewu Plains were fertile for rice farming but were more isolated from the coast.

Recent studies suggest the move was not sudden. Mataram likely already had settlements in East Java. The move was probably gradual and caused by many factors. The Sanggurah inscription (982 AD) from Malang, East Java, mentions King Wawa ruling the Malang area. This shows that East Java was already part of Mataram.

Whatever the true reasons, this move changed the kingdom greatly. Temple building decreased in size and number. The East Java period of Mataram has no grand temples like those in Central Java. It seems the kingdom no longer had the resources for such huge projects.

Building the Eastern Kingdom

The Turyan inscription (929 AD) says Sindok first moved the capital to Tamwlang. Then he moved it again to Watugaluh. Historians think these are the Tambelang and Megaluh areas near modern Jombang, East Java. Sindok started a new family, the Isyana dynasty, named after his daughter. But he was closely related to the Mataram royal family. So, his rule was a continuation of the Javanese kings.

During his rule, Sindok made many inscriptions. Most of them were about setting up Sima lands. These inscriptions show that Sindok was strengthening his power in East Java. Villages were declared Sima lands. This meant they had developed rice farming and could be taxed. They also swore loyalty to Sindok's kingdom.

The Anjukladang inscription from 937 AD is very important. It says Anjukladang village received Sima status. A temple was built there to thank them for fighting off invaders from Malayu. Malayu likely refers to Srivijaya. This means relations between East Javanese Mataram and Srivijaya had become very bad.

Expanding to Bali

Sindok was followed by his daughter, Isyana Tunggawijaya. The Gedangan inscription (950 AD) says Queen Isyana married Sri Lokapala, a nobleman from Bali. Her son, Makutawangsa Wardhana, became king around 985 AD. The Pucangan inscription (1041 AD) says King Makutawangsa Wardhana had a daughter named Mahendradatta. Dharmawangsa Tguh became king around the 990s.

Later, King Dharmawangsa moved the capital again to Wwatan, near modern Madiun. Dharmawangsa's sister, Mahendradatta, married a Balinese king, Udayana Warmadewa. This shows that Bali had become part of the Mataram Kingdom's influence, probably as a vassal. King Dharmawangsa also ordered the translation of the Mahabharata into Old Javanese in 996 AD.

The Collapse of Mataram

In the late 10th century, the rivalry between Srivijaya (Sumatra) and Mataram (Java) grew worse. This might have been because Srivijaya wanted to take back lands in Java. Or Mataram wanted to challenge Srivijaya's power. The Anjukladang inscription (937 AD) already mentioned an attack from Malayu (Srivijaya).

War with Srivijaya

In 990 AD, Dharmawangsa launched a sea invasion against Srivijaya. Chinese records from the Song period mention this. In 988, an envoy from Srivijaya went to China. After two years, he learned his country was attacked by Java. So, he couldn't go home. In 992, a Javanese envoy told the Chinese court that Java was fighting Srivijaya. In 999, the Srivijayan envoy sailed back to China. He asked the Chinese Emperor for protection against the Javanese.

Dharmawangsa's invasion made the Srivijayan king, Sri Cudamani Warmadewa, ask China for help. King Cudamani Warmadewa was a smart ruler. He gained China's political support during the invasion. In 1003, Chinese records say Srivijaya built a Buddhist temple to pray for the Chinese Emperor. They asked the emperor to name the temple and give it a bell. The emperor named it Ch'eng-t'en-wan-shou and sent a bell to Srivijaya.

After 16 years of war, in 1006, Srivijaya pushed back the Mataram invaders. They freed Palembang. This attack showed Srivijaya how dangerous Mataram could be. So, Srivijaya planned to destroy its Javanese enemy.

The Great Disaster

In return, in 1016–1017, Srivijaya helped Haji (king) Wurawari to rebel. Wurawari attacked and destroyed the Mataram Palace. King Dharmawangsa and most of the royal family were killed. Wurawari was a local ruler from the Banyumas area. This sudden attack happened during Dharmawangsa's daughter's wedding. The court was not ready and was shocked.

Javanese records call this disaster the pralaya (the debacle). It was the end of the Mataram kingdom. With Dharmawangsa dead and the capital fallen, the kingdom collapsed into chaos. Local leaders in Central and East Java rebelled. They formed their own small kingdoms. Raids and robberies were common. The country faced more unrest for several years.

Airlangga, the son of King Udayana Warmadewa of Bali and Queen Mahendradatta, survived. He was also King Dharmawangsa's nephew. He escaped and hid in the Vanagiri forest in Central Java. Later, he gathered support and reunited the parts of the Mataram Kingdom. He re-established the kingdom (including Bali) in 1019. This new kingdom was called the Kingdom of Kahuripan. Its capital was near the Brantas river, in East Java.

The Ruling Families

The Two Dynasties Idea

Historian Bosch suggested that King Sanjaya started the Sanjaya Dynasty. He believed two dynasties ruled Central Java: the Buddhist Shailendra and the Hindu Sanjaya dynasty. Inscriptions show Sanjaya was a strong follower of Shaivism (Hinduism). From its start in the early 700s until 928, the Sanjaya dynasty ruled. Sanjaya ruled the Mataram region near modern Yogyakarta and Prambanan.

However, around the mid-700s, the Shailendra dynasty appeared. They challenged Sanjaya's power. Most historians believe the Shailendra and Sanjaya dynasties lived together peacefully. The Shailendra, with their strong ties to Srivijaya, gained control of Central Java. They became the overlords of local Javanese lords (Rakai), including the Sanjayas. This made the Sanjaya kings of Mataram their vassals. We don't know much about the kingdom during this time because the Shailendra were so powerful. They built Borobudur, a huge Buddhist monument.

Samaratungga, the Shailendra king, tried to secure his family's power in Java. He made an alliance with the Sanjayas. He arranged for his daughter, Pramodhawardhani, to marry Rakai Pikatan.

Around the mid-800s, relations between the Sanjaya and Shailendra worsened. In 852, the Sanjaya ruler, Pikatan, defeated Balaputra. Balaputra was the son of the Shailendra king Samaratunga and Princess Tara. This ended the Shailendra presence in Java. Balaputra went back to the Srivijayan capital in Sumatra. There, he became the main ruler. Pikatan's victory was recorded in the Shivagrha inscription from 856 AD. This inscription was made by Rakai Kayuwangi, Pikatan's successor.

The Single Dynasty Idea

Some Indonesian historians disagree with the idea of two dynasties. Historian Poerbatjaraka suggested there was only one kingdom and one dynasty: the Mataram kingdom and the Shailendra dynasty.

This idea is supported by studies of the Sojomerto inscription and the Carita Parahyangan manuscript. Poerbatjaraka believes Sanjaya and his family belonged to the Sailendra family. They were originally Hindu (Shivaist). However, according to the Raja Sankhara inscription (now lost), Sanjaya's son, Panangkaran, became a Buddhist. Because of this, later Sailendra kings who ruled Mataram also became Buddhists. They supported Buddhism in Java until Samaratungga's rule ended.

Hinduism regained royal support with Pikatan's rule. This continued until the end of the Mataram Kingdom. During the reigns of Kings Pikatan and Balitung, the royal Hindu temple of Prambanan was built and expanded near Yogyakarta.

Government and Daily Life

The detailed carvings on Mataram-era temples show a complex Javanese society. It had different social levels and a refined culture.

The Capital City

During this time, cities as we know them today (centers of politics, religion, and trade) were not fully developed in ancient Java. True urban development happened later, in the 13th-century Majapahit's Trowulan.

The capital usually referred to the palace. This was a walled area called pura (Sanskrit) or karaton (Javanese). The king and his family lived and ruled there. The palace was a collection of wooden pavilions. These buildings have decayed over time, leaving only stone walls and bases. Ratu Boko shows what these secular buildings might have looked like. Ancient Javanese cities did not have walls like Chinese or Indian cities. Only the king's palace and temple compounds were walled and guarded. The nagara (capital) was more like many busy villages around the king's palace.

Religious centers, where temples stood, were not always the administrative or economic centers. Inscriptions show that land was given Sima status. Part or all of its rice tax went to building and maintaining temples. However, the Prambanan Plain had many temples close together. This area might have been Mataram's capital. Other experts think Prambanan was the religious center, but not the administrative one. They suggest other places in Muntilan as the political center.

Most of the time, the Mataram Kingdom's court was in Mataram. This was possibly in Muntilan or the Prambanan Plain near modern Yogyakarta. But during Rakai Pikatan's rule, the court moved to Mamrati. Later, under Balitung, it moved to Poh Pitu. Historians don't know the exact locations of Mamrati and Poh Pitu. But most agree they were in the Kedu Plain, near modern Magelang or Temanggung. Later, in the East Java period, other centers were mentioned: Tamwlang and Watugaluh (near Jombang), and Wwatan (near Madiun).

How the Government Worked

During this period, the Javanese government had two main levels. The central government was at the king's court. The other level was the wanua or village. Villages were like "islands" of houses and gardens in large rice fields. This village layout is still seen in modern Javanese desa.

The King was the supreme ruler, like a chakravartin. He had the highest power. He ruled the nagara (kingdom) from his puri (palace). Under the king were state officials called Rakai or Samget. They carried out the king's laws. The Rakais ruled a watak, which was a group of villages. A Rakai was like a regional landlord who managed many villages. They passed the king's orders to the Rama (village leaders).

As the kingdom grew, more officials were added. Most inscriptions from Mataram are about setting up sima lands. This shows how Javanese farming villages grew. A sima was a rice farm that produced extra rice for taxes. It was officially recognized by the king. Most sima lands were ruled by regional rakai or samget. Getting sima status gave a region more prestige. But it also meant recognizing the king's power and swearing loyalty. The Rakais could collect taxes, but some had to be sent to the king's court. Sometimes, sima land became tax-free. In return, the rice from it was used to build or maintain a religious building. This meant the rakai lost some tax income.

Besides ruling and defending, the king and royal family also supported arts and religion. They could start public projects, like irrigation or temple building. Their support for art and religion is seen in the many temples they sponsored. The kingdom built Borobudur, Prambanan, Sewu, and Plaosan temple complex.

The Economy

Most people were farmers, especially growing rice. But some had other jobs, like traders, artisans, soldiers, dancers, or musicians. Temple carvings show many scenes of daily life in 9th-century Java. Rice farming was the main part of the economy. Villages paid taxes to the court with their rice harvest. The fertile volcanic soil of Central Java and wet rice farming helped the population grow. This provided many workers for the kingdom's projects.

Economic activity was not just in one marketplace. Markets likely moved daily among villages, a system called pasaran. This system still exists in some rural Javanese villages today. People traded goods (barter) and also used money. The Javanese economy used money during this time.

The Wonoboyo hoard, a collection of gold items found in 1990, shows the wealth and art of Mataram. It included gold coins shaped like corn seeds. This suggests that money was used in the 9th-century Javanese economy. The coins had the letter "ta" engraved, short for "tahil," an old Javanese money unit.

Culture and Society

Society

We can learn about ancient Javanese society from temple carvings and old inscriptions. The kingdom had a complex society with different social groups. It also had a national government. Ancient Javanese society recognized the Hindu catur varna or caste system. This included Brahmana (priests), Kshatriya (kings and nobles), Vaishya (traders), and Shudra (servants). However, the caste system in ancient Java was less strict than in India.

Historians divide ancient Javanese society into groups:

- Commoners: Most of the people, mainly villagers. They wore simple clothes and few ornaments.

- The King and Royal Family: This included nobles and ruling elites. They wore fancy clothes and many gold jewels. Gods and goddesses in carvings also looked like nobles, but with a special glow around their heads.

- Royal Servants/Lower Nobles: These were king's helpers, guards, or officials. They wore long clothes and some jewelry, but not as much as the king.

- Religious Figures: Priests (brahmins) and Buddhist monks. Monks usually had shaved heads and robes. Brahmins often had beards and wore turbans.

Religion

Hinduism and Buddhism were the main religions. But common people likely also practiced local spiritual beliefs. At first, Mataram kings favored Shivaist Hinduism. King Sanjaya built a Shiva temple, as mentioned in the Canggal inscription. However, during King Panangkaran's rule, Mahayana Buddhism became popular. Temples like Kalasan, Sari, Sewu, Mendut, Pawon, and the grand Borobudur show this Buddhist growth. The kings supported Buddhism from Panangkaran to Samaratungga.

During Pikatan's rule, Shivaist Hinduism became popular again. This is seen in the building of the grand Shivagrha (Prambanan).

The kingdom respected the authority of priests (brahmins). Buddhism was also strong, with Buddhist monks living in monasteries like Sari and Plaosan. These religious leaders performed rituals in temples. The royal family also took part in spiritual life. Some kings, like Panangkaran, were deeply influenced by Buddhism. Rakai Pikatan even retired to become a hermit.

From the late 700s to the early 900s, many temples were built. This might have been due to strong religious belief, the kingdom's wealth, or political reasons. Some historians think building temples was a way to control local landlords (Rakai). By making them fund temples, the king limited their wealth. This stopped them from raising armies to challenge the king. Landlords might have agreed because refusing would harm their reputation.

Art and Architecture

We learn about ancient Javanese society from temple carvings and archaeological finds. The Wonoboyo hoard is a collection of golden artifacts. It shows the wealth, art, and skill of Mataram's ancient goldsmiths. These items are thought to be from King Balitung's time. They likely belonged to a noble or royal family member.

The earliest temple in Mataram, Central Java, was the Hindu Shivaist Gunung Wukir temple. It was built by King Sanjaya around 732 CE. About 50 years later, the oldest Buddhist temple, Kalasan, was built in the Prambanan area. This was linked to King Panangkaran in 778 CE. From then on, many temples were built. These included Sari, Manjusrigrha, Lumbung, Ngawen, Mendut, Pawon. The peak was the building of Borobudur, a huge stone mandala temple, finished around 825 CE.

The grand Hindu temple of Prambanan near Yogyakarta is a great example of Mataram art. It was started during King Pikatan's rule (838–850 AD) and expanded until Balitung's reign (899–911 AD). The Shivagrha inscription describes this temple dedicated to Shiva. It also mentions a project to change the course of the Opak river near the temple. Prambanan was dedicated to the Trimurti (Shiva, Brahma, Vishnu), the three main Hindu gods. It was the largest Hindu temple ever built in Indonesia. It shows the kingdom's great wealth and cultural achievements.

Other Hindu temples from Mataram include Sambisari, Gebang, Barong, Ijo, and Morangan. Even though Hinduism gained favor, Buddhism was still supported by the kings. The Sewu temple, dedicated to Manjusri, was probably started by Panangkaran. It was finished during Rakai Pikatan's rule. He was married to a Buddhist princess, Pramodhawardhani. Most people kept their old religions. Hindus and Buddhists seemed to live together peacefully. Buddhist temples like Plaosan, Banyunibo, and Sajiwan were built during King Pikatan and Queen Pramodhawardhani's rule. This might have been to promote religious harmony after earlier conflicts.

Literature

From the 9th to mid-10th centuries, Mataram saw a flourishing of art, culture, and literature. Hindu-Buddhist sacred texts were translated. Their ideas were adapted into Old Javanese writings and temple carvings. For example, the carvings on Mendut temple and Sojiwan temple tell popular Jataka Buddhist tales. These are stories about the Buddha's past lives.

The Borobudur carvings have the most complete Buddhist stories. They show the law of karma, the story of the Buddha, and tales of virtuous deeds.

The Hindu epic Ramayana is carved on the walls of Prambanan's Shiva and Brahma temples. Stories of Krishna from the Bhagavata Purana are on the Vishnu temple. During this time, the Kakawin Ramayana was written in Old Javanese. This version, also called the Yogesvara Ramayana, is thought to be by Yogesvara around the 9th century CE. He worked at the Mataram court. It has 2774 stanzas and mixes Sanskrit with old Javanese prose. The Javanese Ramayana is different from the original Indian version.

Mataram's Neighbors

Mataram had very close ties with Srivijaya in Sumatra. At first, their relationship was friendly. The Shailendra kings of Java and the Srivijayan kings seemed to have joined families. But later, their relationship turned into war. Dharmawangsa tried to capture Palembang but failed. Srivijaya then planned a strong revenge. On its eastern side, Mataram seemed to control neighboring Bali, bringing the island under its influence.

Khmer art and architecture during the early Angkor era were also influenced by Javanese art. The Bakong temple in Cambodia looks very similar to Borobudur. This strongly suggests that Bakong was inspired by Borobudur's design. There must have been travelers or missions between Kambuja and Java. They shared ideas and building techniques, including arched gateways.

The Kaladi inscription (around 909 CE) mentions Kmir (Khmer people of the Khmer Empire), Campa (Champa), and Rman (Mon). These were foreigners from mainland Southeast Asia who often came to Java to trade. This inscription suggests that a sea trade network existed between these kingdoms and Java.

The name of the Medang Kingdom is mentioned in the Laguna Copperplate Inscription from the Philippines' Tondo. This inscription, from around 900 CE, was found in Lumban, Laguna. It was written in the Kawi script and used Old Malay words. It also had some words that could be from Old Javanese or Old Tagalog. This suggests that people or officials from the Mataram Kingdom traded and had relations with regions as far as the Philippines. It shows that ancient kingdoms in Indonesia and the Philippines were connected.

Mataram's Lasting Impact

The Mataram kingdom era is known as the golden age of ancient Indonesian civilization. It left a lasting mark on Indonesian culture and history through its monuments. The grand Borobudur and Prambanan are a source of national pride for all Indonesians. They are like the Angkorian legacy for the Khmer people of Cambodia. Today, these monuments are major tourist attractions. Borobudur is the most visited tourist site in Indonesia.

Indonesia has never seen such a strong passion for building and temple construction again. This era showed amazing technical skill, labor management, art, and architectural achievement. From the late 700s to the late 800s, many impressive religious monuments were built. These include Manjusrigrha, Bhumisambharabudhara, and Shivagrha.

The Mataram era is called the classical period of Javanese civilization. During this time, Javanese culture, art, and architecture blossomed. They combined their local traditions with Hindu-Buddhist influences. By adding Hindu-Buddhist ideas to their culture, art, and language, the Javanese created their own unique style. This Javanese style of Sailendran art then influenced art in Sumatra and Southern Thailand.

During this period, many Hindu and Buddhist scriptures came from India to Javanese culture. For example, Buddhist Jataka tales and Hindu epics like Ramayana and Mahabharata were adapted into Javanese versions. These stories continue to shape Javanese culture and performing arts, such as Javanese dances and wayang (shadow puppet) art.

List of Mataram Rulers

Here are the kings and queens of the Mataram Kingdom:

| Years Ruled | King/Queen | Important Inscriptions and Events |

|---|---|---|

| 716–746 | Rakai Matarām Saŋ Ratu Sañjaya Narapati Raja Śrī Sañjaya (Sanjaya) |

Mentioned in Canggal inscription (732) and Mantyasih inscription (907). Declared himself a great ruler. |

| 746–784 | Śrī Mahārāja Dyaḥ Pañcapaṇa Kariyāna Paṇaṃkaraṇa Śrī Saṅgrāmadhanañjaya (Dyah Pancapana) |

Mentioned in Kalasan inscription (778) and Kelurak inscription (782). Built Buddhist temples like Tarabhawanam and Manjusrigrha. |

| 784–803 | Śrī Mahārāja Rakai Panaraban | Mentioned in Wanua Tengah inscription (908). |

| 803–827 | Śrī Mahārāja Rakai Warak Dyaḥ Manara (Dyah Manara) |

Mentioned in Wanua Tengah inscription (908). |

| 827–829 | Dyaḥ Gula (Dyah Gula) |

Mentioned in Wanua Tengah inscription (908). |

| 829–847 | Śrī Mahārāja Rakai Garuŋ | Mentioned in Wanua Tengah inscription (908). |

| 847–885 | Śrī Mahārāja Rakai Pikatan Dyaḥ Saladu Saŋ Prabhu Jātiniṅrat (Dyah Saladu) |

Mentioned in Shivagrha inscription (856) and Mantyasih inscription (907). Built a palace in Mamratipura and Hindu and Buddhist temples like Shivagrha and Plaosan. |

| 885–885 | Śrī Mahārāja Rake Kayuwaṅi Dyaḥ Lokapāla Śrī Sajjanotsawatuṅga (Dyah Lokapala) |

Mentioned in Shivagrha inscription (856) and Mantyasih inscription (907). |

| 885–885 | Śrī Mahārāja Dyaḥ Tagwas Śrī Jayakirtiwarddhana (Dyah Tagwas) |

Mentioned in Er Hangat (888) and Wanua Tengah (908). Ruled for a very short time. |

| 885–887 | Śrī Mahārāja Rake Panumwaṅan Dyaḥ Dewendra (Dyah Dewendra) |

Mentioned in Wanua Tengah inscription (908). Became king in August 885, then was forced out. |

| 887–887 | Śrī Mahārāja Rake Gurunwaṅi Dyaḥ Bhadra (Dyah Bhadra) |

Mentioned in Wanua Tengah inscription (908). Ruled for less than a month in 887. |

| 894–898 | Śrī Mahārāja Rake Wuṅkalhumalaŋ Dyaḥ Jbaŋ (Dyah Jbang) |

Mentioned in Wanua Tengah inscription (908). |

| 898–908 | Śrī Mahārāja Rake Watukura Dyaḥ Balituŋ Śrī Dharmmodaya Mahāsambhu (Dyah Balitung) |

Mentioned in many inscriptions, including Mantyasih inscription (907). |

| 908–919 | Śrī Mahārāja Rake Hino Dyaḥ Daksottama Bāhubajrapratipakṣakṣaya Śrī Mahottuṅgawijaya (Dyah Daksottama) |

Mentioned in Pangumulan (902) and Tihang (914) inscriptions. |

| 919–924 | Śrī Mahārāja Rakai Layaŋ Dyaḥ Tlodhong Śrī Sajjana Sannatanuraga Uttuṅgadewa (Dyah Tlodhong) |

Mentioned in Sukabumi (804) and Lintakan (919) inscriptions. |

| 924–929 | Śrī Mahārāja Rakai Paṅkaja Dyaḥ Wawa Śrī Wijayalokanāmottuṅga (Dyah Wawa) |

Mentioned in Sukabumi (927) and Sangguran (928) inscriptions. |

| The kingdom's center moved to East Java, led by the Ishana dynasty. | ||

| 929–947 | Śrī Mahārāja Rake Hino Dyaḥ Siṇḍok Śrī Īśānawikrama Dharmottuṅgadewawijaya (Dyah Sindok) |

Mentioned in Turyan (929) and Anjukladang (937) inscriptions. Moved the capital to East Java and started the Ishana dynasty. |

| 947–985 | Śrī Īśānatuṅgawijaya (Ishanatunga) |

Mentioned in Gedangan (950) and Pucangan (1041) inscriptions. |

| 985–990 | Śrī Makuṭawaṅśāwarddhana (Makutawangsa) |

Mentioned in Pucangan inscription (1041). |

| 990–1016 | Śrī Īśānadharmmawaṅśātguh Anantawikramottuṅgadewa (Dharmawangsa) |

Mentioned in Pucangan inscription (1041). The kingdom fell due to a revolt by Haji Wurawari. |

See also

In Spanish: Reino de Medang para niños

In Spanish: Reino de Medang para niños

| Toni Morrison |

| Barack Obama |

| Martin Luther King Jr. |

| Ralph Bunche |