Mandala facts for kids

A mandala is a special symbol used in Hinduism and Buddhism. The word "mandala" comes from an old language called Sanskrit and means "circle." These beautiful designs often show the whole universe. Most mandalas are shaped like a square with four "gates" or entrances. Inside the square, there's a circle with a dot in the middle. Mandalas are usually balanced and symmetrical, like a perfect circle.

People use mandalas for many spiritual reasons. They can help you focus your mind during meditation. They also help create a special, sacred space. Mandalas can guide you on a spiritual journey. They often represent a path from the outside world to your inner self.

In religions like Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, and Shinto, mandalas can be like maps. They might show gods, goddesses, or even heavenly places.

Contents

Sand Mandalas: Art That Disappears

Sand mandalas are amazing, colorful artworks made from tiny grains of sand. What makes them special is that they are ritually destroyed after they are finished. This tradition started in India many centuries ago. Today, it is mainly practiced in Tibetan Buddhism.

Each sand mandala is made for specific deities or spiritual figures. In Buddhism, these figures represent different states of mind. The mandala itself shows the "palace" of a deity. This also represents the deity's mind.

Monks create these mandalas after years of training. They first draw a detailed sketch. Then, they use colorful sand, often made from powdered stones. They pour the sand through special copper funnels called Cornetts. They gently tap the funnels to let the sand fall slowly. Each color used has a special meaning related to the deities.

While making the mandalas, the monks pray and meditate. Every grain of sand is said to represent a blessing. The destruction of the sand mandala is very important. It teaches about impermanence. This is the Buddhist belief that nothing lasts forever. It also shows that we shouldn't get too attached to things. After the mandala is destroyed, the sand is often poured into a river. This symbolizes the blessings returning to the world.

Mandalas in Ancient Cultures

Mayan Calendars

The ancient Maya people created calendars that looked a lot like mandalas. Their famous Tzolkʼin calendar, which had 260 days, had a circular design. It was similar in shape and purpose to the "Wheel of Time" sand paintings of Tibetan Buddhists.

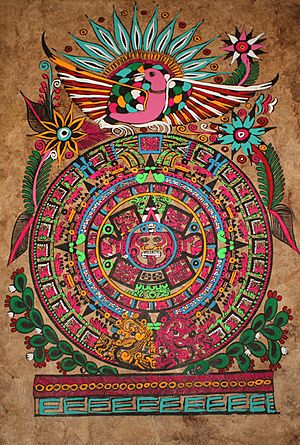

Aztec Sun Stone

The Aztec Sun Stone is a huge, carved stone. Many people think it represents the entire universe as the Aztec people saw it. In some ways, it looks like a giant mandala.

When the stone was first found, people thought it was mainly a calendar. Some of the circles on the stone show symbols for the days of the month. The stone also shows four past "suns" or eras that the Aztecs believed the Earth had gone through.

The Sun Stone also had deep religious meaning. One idea is that the face in the middle is Tonatiuh, the Aztec sun god. That's why it's called the "Sun Stone." Other experts believe the face might be Tlaltecuhtli, the Aztec earth goddess. Modern archaeologists think the stone was likely used for important ceremonies or rituals.

The stone might also have geographic meaning. Its four main points could represent the four directions or corners of the Earth. The inner circles might show space as well as time.

Finally, the stone could have a political meaning. It might have shown Tenochtitlan, the Aztec capital, as the center of the world. This would mean it was the center of power. Some small symbols on the stone might even refer to important historical events for the Aztec state.

Mandalas in Christianity

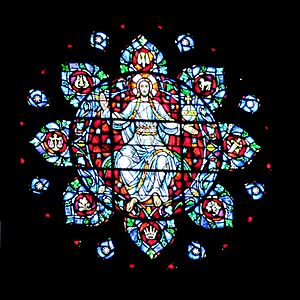

Some old Christian artworks and designs look like mandalas. For example, the Cosmati pavements are geometric mosaic designs from Italy in the 1200s. The Great Pavement at Westminster Abbey in England is one such example. It is believed to show divine and cosmic patterns.

Many drawings by Hildegard of Bingen, a famous Christian mystic, can also be seen as mandalas. Some images in esoteric Christianity, which explores deeper spiritual meanings, also have mandala-like qualities.

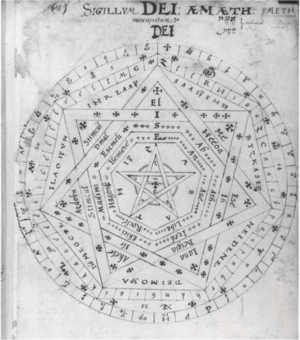

John Dee, an alchemist and mathematician, created a geometric symbol called the Sigillum Dei (Seal of God). This symbol showed a universal geometric order. It included the names of archangels.

The Layer Monument, a marble monument from the early 1600s in a church in Norwich, England, is another example. It uses alchemical symbols to create a mandala in Christian art.

Mandalas in Architecture

Buddhist architecture often uses mandalas as a blueprint for buildings. This includes temple complexes and stupas (dome-shaped structures). A great example is the Borobudur temple in Indonesia. It was built in the 800s.

Borobudur is a huge stupa surrounded by smaller ones. They are arranged on terraces that look like a stepped pyramid. When you look at it from above, it forms a giant Buddhist mandala. This design shows the Buddhist view of the universe and the nature of the mind. Other temples from the same time also have mandala plans. You can see similar designs in Cambodia, Thailand, and Myanmar.

Mandalas in Art

Mandalas first appeared as an art form in Buddhist art in India around the first century BCE. You can also see mandala-like designs in Rangoli art. These are colorful patterns made on floors in Indian households.

In modern times, especially in the New Age movement, a mandala is seen as a diagram or pattern. It represents the cosmos in a symbolic way. It can be like a small version of the universe. It also represents wholeness and how life is organized.

Mandalas in Archaeology

Recently, archaeologists made an exciting discovery in India using Google Earth. They found five giant mandalas in the valley of Manipur. These huge designs are made entirely of mud in paddy fields. The Maklang geoglyph, near Imphal, might be the world's largest mud mandala.

This site was only discovered in 2013 because its full shape can only be seen from satellite images. The local government now protects this paddy field as a historical monument. It covers a huge area, about 224,161 square meters. This square mandala has four large rectangular "gates" pointing in the main directions. Inside, there's an eight-petaled flower or star shape.

Other large mandalas have also been found in Manipur using Google Earth. These include the Sekmai mandala and the Phurju twin mandalas. More recently, in 2019, two other large mandala-shaped designs were reported.

Images for kids

-

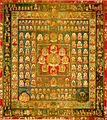

The Womb Realm mandala. The center square represents the young stage of Vairocana. He is surrounded by eight Buddhas and bodhisattvas (clockwise from top: Ratnasambhava, Samantabhadra, Saṅkusumitarāja, Manjushri, Amitābha, Avalokiteśvara, Amoghasiddhi and Maitreya)

-

Painted 17th-century Tibetan 'Five Deity Mandala', in the centre is Rakta Yamari (the Red Enemy of Death) embracing his consort Vajra Vetali, in the corners are the Red, Green, White and Yellow Yamaris, Rubin Museum of Art

-

Sandpainting showing Buddha mandala, which is made as part of the death rituals among Buddhist Newars of Nepal

-

Chenrezig sand mandala created at the House of Commons of the United Kingdom on the occasion of the Dalai Lama's visit in May 2008

-

Aerial view of the Boudhanath stupa resembles a mandala

-

7th century buddhist monastery in Bangladesh. Somapura Mahavihara

See also

In Spanish: Mandala para niños

In Spanish: Mandala para niños

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |