Mataram Sultanate facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Sultanate of Mataram

|

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1586–1755 | |||||||||||||

|

Flag

|

|||||||||||||

The maximum extent of Mataram Sultanate during the reign of Sultan Agung Anyokrokusumo (1613–1645)

|

|||||||||||||

| Capital | Kota Gede (1586–1613) Karta (1613–1645) Plered (1646–1680) Kartosuro (1680–1755) |

||||||||||||

| Common languages | Javanese | ||||||||||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam (syncretized) | ||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||

| King (Susuhunan / Sultan) | |||||||||||||

|

• 1586–1601 (first)

|

Senopati | ||||||||||||

|

• 1743–1749 (last)

|

Pakubuwono II | ||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||

|

• Coronation

|

1586 | ||||||||||||

|

• Treaty of Giyanti

|

13 February 1755 | ||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

| Today part of | Indonesia | ||||||||||||

|

The incident is referred to in Javanese as Palihan Nagari.

|

|||||||||||||

The Sultanate of Mataram was a powerful Javanese kingdom on the island of Java. It was the last big independent Javanese kingdom before the Dutch took control. Mataram was the main power in Central Java from the late 1500s to the early 1700s.

The kingdom was strongest during the time of Sultan Agung Anyokrokusumo (1613–1645). After he died in 1645, Mataram started to lose its power. By the mid-1700s, it had lost much land and power to the Dutch East India Company (VOC). By 1749, it had become a kingdom controlled by the Dutch.

Contents

What's in a Name?

The name Mataram was never the official name of the kingdom. Javanese people often called their land Bhumi Jawa or Tanah Jawi, meaning "Land of Java". Mataram refers to the flat areas south of Mount Merapi in present-day Yogyakarta. Specifically, it points to the Kota Gede area, which was the capital of the Sultanate.

It was common in Java to name a kingdom after its capital city. There were two kingdoms in this area called Mataram. The later one is often called Mataram Islam or "Mataram Sultanate" to tell it apart from an older Hindu-Buddhist kingdom from the 800s.

How We Know About Mataram

We learn about the Mataram Sultanate from Javanese historical stories called Babad. We also get information from the Dutch Dutch East India Company (VOC). The Javanese Babad stories sometimes mix history with myths and legends. For example, some stories say that Panembahan Senapati, an early king, had a special connection with the mythical Ratu Kidul, the queen of the Southern Seas. These stories were used to make the rulers seem more powerful and legitimate.

It's hard to know the exact dates for events before Sultan Agung's time. But for events after 1628, especially those involving the Dutch, the dates are more certain.

Mataram's Story

How Mataram Began and Grew

Starting the Kingdom

Javanese stories say that the Mataram kings came from a person named Ki Ageng Sela. In the 1570s, one of his family members, Kyai Gedhe Pamanahan, was given the land of Mataram. This was a reward from the King of Pajang, Sultan Hadiwijaya, for defeating his enemy. Pajang was near modern-day Surakarta. Mataram was first a smaller state under Pajang. Pamanahan was often called Kyai Gedhe Mataram. A kyai is a respected Muslim religious leader.

After Sultan Hadiwijaya died in 1582, there were big power struggles in Pajang. Pamanahan's son, Sutawijaya (also known as Panembahan Senapati), took over around 1584. He started to make Mataram independent from Pajang. Under Sutawijaya, Mataram grew a lot by fighting against Pajang. The new Pajang Sultan, Arya Pangiri, was not popular. Prince Benowo, Hadiwijaya's son, asked Sutawijaya for help to get his throne back. Mataram and Prince Benowo attacked Pajang and defeated it. In 1586, Pajang ended, and Mataram became the new powerful kingdom.

Mataram Becomes Strong

Senapati became king and took the title "Panembahan". He started to expand his kingdom. In 1586, the rich port city of Surabaya fought against him, but Senapati couldn't capture it. He then conquered other cities like Madiun (1590-1) and Kediri (1591). He also took control of Cirebon and Galuh in West Java in 1595. His attempt to conquer Banten in 1597 failed. Panembahan Senapati died in 1601 and was buried in Kota Gede. He had built a strong foundation for the new kingdom.

His son, Panembahan Anyokrowati (around 1601–1613), faced many rebellions. He also fought against Surabaya, which was a major power in East Java. In 1612, Surabaya rebelled again. Anyokrowati attacked areas around Surabaya but couldn't conquer the city itself.

The first time Mataram met the Dutch East India Company (VOC) was during Anyokrowati's rule. The Dutch were mostly trading from coastal towns. Anyokrowati died in 1613 while hunting and was given the title Panembahan Seda ing Krapyak (His Majesty who Died in Krapyak).

The Golden Age

Anyokrowati's son, Raden Mas Rangsang, became king in 1613. In 1641, he took the title Sultan Agung Anyokrokusumo ("Great Sultan"). Sultan Agung's rule is remembered as the best time for Mataram. It was a golden age for Javanese power before European countries took over.

Conquering Surabaya and the East

Sultan Agung was a skilled military leader who wanted to unite all of Java under Mataram. He greatly expanded Mataram's land from 1613 to 1646. He captured many port cities in northern Java. Surabaya, with its strong defenses and swamps, was Mataram's toughest enemy. In 1614, Surabaya formed an alliance and attacked Mataram. Sultan Agung fought them off and conquered Malang. He also took Lasem in 1616 and Tuban, a big port city, in 1619.

Surabaya was very hard to defeat. Sultan Agung tried to weaken it by attacking its allies. He captured Sukadana in southwest Kalimantan in 1622 and the island of Madura in 1624. After five years of war, Agung finally conquered Surabaya in 1625. He didn't invade directly but surrounded the city, cutting off its food supply until the people surrendered.

With Surabaya under control, Mataram ruled most of Central and Eastern Java, plus Madura and Sukadana. Sultan Agung made his power stronger by arranging marriages between his nobles and Mataram princesses. He also married a Cirebon princess to make Cirebon a loyal ally. By 1625, Mataram was the undisputed ruler of Java.

Campaigns in the West

In West Java, Banten and the Dutch settlement in Batavia were still free from Agung's control. Agung wanted to unite all of Java, so he saw the Dutch in Batavia as a threat.

In 1628, Agung and his armies started to attack Batavia. It was hard because his troops didn't have enough supplies. Agung tried to set up farms and send rice by ship to feed his army. But the Dutch found and destroyed these supplies. Many Mataram troops suffered from hunger. In the end, Agung's attempt to take Batavia failed.

Putting Down Rebellions

After the failed Batavia campaign, some parts of Mataram rebelled. In 1630, Mataram crushed a rebellion in Tembayat. From 1631 to 1636, they had to stop rebellions in West Java. Some historians think these rebellions happened because Agung's failure at Batavia made him seem less powerful. But rebellions had happened even before that.

Sultan Agung also launched a "holy war" against the Hindu kingdom of Blambangan in eastern Java. Blambangan was supported by Bali. Blambangan surrendered in 1639 but later became independent again.

In 1641, Sultan Agung received permission from Mecca to use the title "Sultan". His Islamic name became "Sultan Abdul Muhammad Maulana Matarami".

In 1645, Sultan Agung started building Imogiri, his burial place, south of Yogyakarta. Many Javanese royals are still buried there today. Agung died in 1646. He left behind a large empire covering most of Java and some nearby islands.

Mataram's Decline

Power Struggles

Sultan Agung's son, Susuhunan Amangkurat I, became king. He tried to make Mataram stable by killing local leaders who didn't respect him enough. He also closed ports and destroyed ships in Javanese coastal cities. This hurt Java's sea trade and made Mataram an inland kingdom. Amangkurat I was known as a ruthless king. He even killed thousands of religious scholars and their families because he thought they were plotting against him.

Unlike his father, Amangkurat I was not a strong military leader. He made a peace agreement with the Dutch in 1646. He moved the capital from Karta to a grander palace in Plered.

By the mid-1670s, people were very unhappy with the king, and a revolt began. The Crown Prince (who would become Amangkurat II) felt unsafe. He secretly helped Raden Trunajaya, a prince from Madura, start a rebellion in East Java. Trunajaya's rebellion quickly grew strong and captured the king's palace in Plered in 1677. The king escaped with his oldest son, Amangkurat II. Trunajaya looted the palace and went back to his stronghold in Kediri.

Amangkurat II and Dutch Control

Amangkurat I died in 1677 while trying to get Dutch help. So, Amangkurat II became king. He had no army or money. To get his kingdom back, he made big promises to the Dutch East India Company (VOC). The Dutch agreed to help him because a stable Mataram, owing them a lot, would be good for their trade.

The Dutch forces defeated Trunajaya in 1678. In 1681, the Dutch and Amangkurat II forced Prince Puger, who had taken the throne, to step down. In 1680, Amangkurat II officially became king with Dutch support. In return, Mataram had to give the Dutch the port city of Semarang and other areas like Bogor and Priangan. Cirebon also became a Dutch protectorate. Amangkurat II moved the capital to Kartasura. The Dutch built a fort there to control the new capital.

The Dutch now had strong control over Amangkurat II. He wasn't happy about it, especially with the Dutch taking over the coast. But he couldn't do much because he owed them so much money and feared their military power. He tried to secretly weaken the Dutch, for example, by helping people the Dutch wanted to catch. One such person was Untung Surapati. In 1685, the Dutch sent Captain Tack to capture Surapati. But the king tricked Tack, and Tack was killed. The Dutch didn't react strongly because they had their own problems in Batavia. By the end of his rule, Amangkurat II was not trusted by the Dutch.

Wars of Succession

Amangkurat II died in 1703. His son, Amangkurat III, became king. But the Dutch decided to support his uncle, Pangeran Puger, instead. This started the First Javanese War of Succession. The war lasted five years. In 1705, Pakubuwono I's forces and the Dutch captured Kartasura. Amangkurat III ran away. In 1708, Amangkurat III surrendered and was sent away to Ceylon (Sri Lanka).

With Pakubuwana I as king, the Dutch gained much more control over Central Java. In 1705, he agreed to give the Dutch Cirebon and eastern Madura. The Dutch also got Semarang as their main base. They could build forts anywhere in Java and had a monopoly on textiles. Mataram had to pay a yearly tribute of rice, wood, indigo, and coffee. These tributes made Pakubuwana I the first true puppet ruler of the Dutch.

The last years of Pakubuwana I's rule (1717-1719) saw more rebellions in East Java. The murder of Jangrana II in 1706 caused his brothers to rebel with help from Balinese fighters. The Dutch captured Surabaya in 1718. But many areas in East Java joined the rebellion.

In 1719, Pakubuwana I died. His son, Amangkurat IV, became king, but his brothers fought him for the throne. This started the Second Javanese War of Succession. The rebels even attacked the palace in 1719. The Dutch helped Amangkurat IV. By 1723, most rebels had surrendered or were sent away. These wars showed that even with their strong military, the Dutch couldn't easily control all of Java.

Court Problems and the Chinese War

After 1723, things seemed calmer. The Javanese nobles learned that working with the Dutch military made them almost unbeatable. In 1726, Amangkurat IV died. His son, Pakubuwana II, became king without much trouble. But there were still many arguments and plots within the court. The king often changed his mind about who to support.

A big problem came from Batavia. In 1740, the Dutch massacred about 10,000 Chinese people in Batavia. Many Chinese fled and started a rebellion.

In 1741, Chinese rebels appeared in Central Java. They captured several towns. The Javanese first helped the Dutch, but then the Chinese ambushed them. The Dutch were in a difficult spot. They decided they had to support Pakubuwana II to keep Java stable for trade.

In September 1741, the king secretly ordered his officials to help the Chinese attack the Dutch. But Dutch reinforcements arrived. By November, the Dutch had pushed back the Chinese and Javanese forces. This made Pakubuwana II change sides again and start talking with the Dutch.

In 1742, the rebels made Raden Mas Garendi, a descendant of Amangkurat III, their new king, calling him Sunan Kuning. In June 1742, the rebels captured Kartasura, forcing Pakubuwana II to flee. The Dutch focused on clearing the northern coast of rebels. By October 1742, the coast was clear. In December, the Dutch helped Pakubuwana II return to Kartasura.

The Chinese war ended in 1743. Mataram had lost much land. By 1743, Mataram only included areas around Surakarta, Yogyakarta, Kedu, and Bagelen.

Mataram is Divided

Because the palace in Kartasura was captured, Pakubuwana II built a new one in Surakarta (Solo) and moved there in 1746. But he was still not safe. Raden Mas Said, also known as Pangeran Sambernyawa ("Soul Reaper"), continued to rebel. He would later start the Mangkunagara princely house in Solo.

Pakubuwana II's brother, Pangeran Mangkubumi, defeated Mas Said in 1746. Mangkubumi wanted a reward, but the king's advisor told the king not to give it. Then, the Dutch governor-general, van Imhoff, visited the palace. He insisted that Pakubuwana II give the Dutch control over coastal and some inland regions. Pakubuwana II agreed. Mangkubumi was very unhappy because the king didn't ask other royal family members. Van Imhoff also insulted Mangkubumi in front of everyone. This made Mangkubumi furious, and he started his own rebellion in May 1746, with Mas Said's help.

In 1749, Pakubuwana II became very sick. He asked the Dutch to take control of the kingdom. On December 11, 1749, Pakubuwana II signed an agreement giving Mataram's "sovereignty" to the VOC.

On December 15, 1749, the Dutch announced Pakubuwana II's son as the new king, Pakubuwana III. However, three days earlier, Mangkubumi also declared himself king in Yogyakarta. His rebellion grew stronger. The Dutch realized they couldn't stop it by force. By 1754, everyone was tired of fighting and ready to talk.

The kingdom of Mataram was divided in 1755 by the Treaty of Giyanti. This treaty split control of Central Java between the Yogyakarta Sultanate, led by Mangkubumi, and Surakarta, led by Pakubuwana. Mas Said was still fighting. In 1756, he almost captured Yogyakarta. But he realized he couldn't defeat all three powers (Solo, Yogya, and the Dutch) alone. In 1757, he surrendered and was given land near Solo, which became the Mangkunegaran Palace. He was given the title "Pangeran Arya Adipati Mangkunegara". This agreement brought peace until 1812.

Mataram's Culture

Even though Mataram was an Islamic Sultanate, it didn't fully adopt Islamic culture. Its political system was a mix of older Javanese Hindu traditions and Islamic ideas. During Sultan Agung's rule, he blended Islam with Hindu-Javanese traditions. He also introduced a new calendar in 1633 that combined Islamic and Javanese practices.

Many Javanese cultural elements, like gamelan music, batik cloth, kris daggers, wayang kulit (shadow puppets), and Javanese dance, were developed and made into their current forms during this time. These traditions were passed down to the later courts of Surakarta and Yogyakarta.

Islam in Java was adapted to the local culture. This made it easier for Javanese people to accept Islam, and it spread quickly and naturally.

Javanese Kingship

Javanese kingship was different from Western kingship. It wasn't based on the idea of being chosen by the people or by God. Instead, the Javanese kingdom was seen as a "mandala," or a center of the world. The king was the central figure. Kings were thought of as semi-divine beings, a mix of divine and human qualities. The kingdom's identity came from the line of these semi-divine kings, not just from its land or people.

List of Mataram Kings

The kings of Mataram first used the title panembahan, then susuhunan. The title sultan was only used from 1641-1645 during the reign of Anyokrokusumo.

- Danang Sutawijaya (Panembahan Senopati) : 1586–1601

- Raden Mas Jolang (Susuhunan Anyokrowati / Sunan Krapyak) : 1601–1613

- Raden Mas Jatmika (Susuhunan Anyokrokusumo / Sultan Agung) : 1613–1645)

- Raden Mas Sayyidin (Susuhunan Amangkurat I / Sunan Tegalarum) : 1646–1677

- Raden Mas Rahmat (Susuhunan Amangkurat II / Sunan Amral) : 1677–1703

- Raden Mas Sutikna (Susuhunan Amangkurat III / Sunan Mas) : 1703–1704

- Raden Mas Darajat (Susuhunan Pakubuwono I / Sunan Ngalaga) : 1704–1719

- Raden Mas Suryaputra (Susuhunan Amangkurat IV / Sunan Jawi) : 1719–1726

- Raden Mas Prabasuyasa (Susuhunan Pakubuwono II / Sunan Kumbul) : 1726–1742

- Raden Mas Garendi (Susuhunan Amangkurat V / Sunan Kuning) : 1742–1743

- Raden Mas Prabasuyasa (Susuhunan Pakubuwono II / Sunan Kumbul) : 1743–1749

- Raden Mas Gustisuriyakusuma (Susuhunan Pakubuwono III / Sunan Prabhu) :1749-1755

Mataram was divided in 1755, after the Third Javanese War of Succession. This event is called 'Palihan Nagari' in Javanese.

Mataram's Lasting Impact

The Mataram Sultanate was the last big native kingdom in Java. After it broke apart, it formed the courts of Surakarta and Yogyakarta, and the princedoms of Mangkunegaran and Pakualaman. These areas were later fully controlled by the Dutch.

For people from Yogyakarta and Surakarta, the Mataram Sultanate, especially Sultan Agung's time, is remembered with pride. It was a glorious past when Mataram almost united all of Java and nearly drove out the Dutch. However, for people from areas that Mataram conquered, like Surabaya, Madura, and West Java, the Mataram era is remembered as a time when Central Java ruled over them, sometimes harshly.

In art and culture, the Mataram Sultanate left a huge mark on Javanese culture. Many Javanese cultural elements, like gamelan, batik, kris, wayang kulit, and Javanese dance, were shaped during this period. These traditions are still carefully kept by the royal courts today. During Mataram's peak, Javanese culture spread widely, influencing parts of West and East Java.

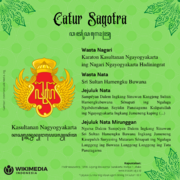

Catur Sagotra

Catur Sagotra means "four entities with one root kinship." It refers to the four royal families that came from the Islamic Mataram dynasty. These are the Kasunanan Surakarta, Kasultanan Yogyakarta, Kadipaten Mangkunagaran, and Kadipaten Pakualaman.

The idea of Catur Sagotra started in 2004. It was a shared idea among the four Javanese kings at that time. The goal of Catur Sagotra is to unite these four royal families through their shared culture and history from their Mataram ancestors.

See also

- List of Sunni Muslim dynasties

- List of monarchs of Java