Sultanate of Cirebon facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Sultanate of Cirebon

كسلطانن چيربون

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1447–1679 | |||||||||||

|

Flag

|

|||||||||||

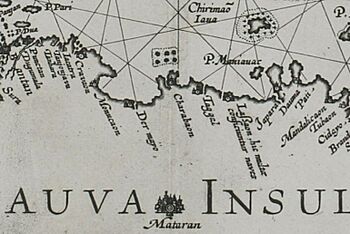

Map of Java from 1598 by Joannes van Doetecum the Elder, showing the city of Cirebon (Charabaon) with a flag on top of it.

|

|||||||||||

| Status | Vassal of the Sunda Kingdom (1445–1515) Puppet state of Demak (1479–1546) Vassal of the Mataram Sultanate (1613–1705) |

||||||||||

| Capital | Cirebon | ||||||||||

| Common languages | Sundanese, Javanese | ||||||||||

| Religion | Islam | ||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||

|

• 1447–1479

|

Prince Cakrabuana | ||||||||||

|

• 1479–1568

|

Syarif Hidayatullah | ||||||||||

|

• 1649–1677

|

Panembahan Ratu II | ||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||

|

• Prince Cakrabuana was appointed as the ruler of Cirebon

|

1447 | ||||||||||

|

• Cirebon Independence from Sunda Kingdom

|

1479 | ||||||||||

|

• Cirebon under the rule of Mataram Sultanate

|

1613 | ||||||||||

|

• First disintegration of the Cirebon Sultanate

|

1677 | ||||||||||

|

• The founding of Kasepuhan and Kanoman

|

1679 | ||||||||||

|

• Final loss of authority to colonial government

|

1679 | ||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

| Today part of | Indonesia | ||||||||||

The Sultanate of Cirebon was an Islamic kingdom in West Java, Indonesia. It was founded in the 15th century. Many people believe it was started by a leader named Sunan Gunungjati. He declared Cirebon independent in 1482, but the area had been settled since 1445. Sunan Gunungjati also helped create the Sultanate of Banten. Cirebon was one of the first Islamic states in Java, along with the Sultanate of Demak.

The capital city was near what is now Cirebon on Java's northern coast. During the 16th and 17th centuries, the sultanate grew strong. It became a major center for trade and learning about Islam. In 1677, the sultanate split into three royal families. A fourth family split off in 1807. Each family had its own palace, called a kraton. These palaces are Kraton Kasepuhan, Kraton Kanoman, Kraton Kacirebonan, and Kraton Kaprabonan. They still exist today and perform important cultural duties.

Contents

What Does "Cirebon" Mean?

There are a few ideas about where the name "Cirebon" comes from.

A Mix of Cultures

One idea is that Cirebon was first a small village. It grew into a busy port town called Caruban. In the Sundanese language, Caruban means "mixture." This name made sense because many different people lived there. They came from various ethnic groups, religions, and spoke different languages.

Shrimp and Water

Another idea is that the name comes from rebon. This is a Sundanese word for small shrimp found in the area. People in the village often fished for these shrimp. They used them to make shrimp paste. The water used to make shrimp paste was called cai rebon. This means "rebon water" in Sundanese. Over time, this name might have changed to Cirebon.

Cirebon's Story

Most of Cirebon's history comes from old Javanese stories called Babad. Important stories include Carita Purwaka Caruban Nagari and Babad Cerbon. Foreign visitors also wrote about Cirebon. For example, Tomé Pires, a Portuguese explorer, mentioned it in his book Suma Oriental around 1512–1515. Later, Dutch records also tell us about the sultanate. One of the royal families, the Keprabonan, also collected old writings to study Java's history.

How Cirebon Began

The area around Cirebon was once part of the Sunda Kingdom. This was a Hindu kingdom. A small fishing village called Muara Jati was located there. It was about 14 kilometers north of modern Cirebon. The village started to change from a Hindu fishing village to a busy Muslim port. This happened when a wealthy merchant named Ki Ageng Tapa became its leader.

Ki Ageng Tapa and His Family

Ki Ageng Tapa was a rich merchant in Muara Jati. The Sunda king made him the port master. Many Muslim traders came to this busy port. Ki Ageng Tapa and his daughter, Nyai Subang Larang, became Muslims. His daughter studied at an Islamic school.

Nyai Subang Larang married King Siliwangi, the Sunda King. They had three children: Prince Walangsungsang, Princess Rara Santang, and Prince Kian Santang. Even though Prince Walangsungsang was the oldest son, he did not become the next king. This was because his mother was not the main queen. Also, he had become a Muslim, while the kingdom's main religions were Sundanese ancestral beliefs, Hinduism, and Buddhism. His half-brother, whose mother was the main queen, became the next king.

In 1442, Prince Walangsungsang married Nyai Endang Geulis. He and his sister Rara Santang traveled to learn about spirituality. They met a Muslim scholar named Sheikh Datuk Kahfi from Persia. They learned about Islam from him. The Sheikh asked the Prince to start a new settlement. Prince Walangsungsang, with help from others, cleared the forests. He started a new village called Dukuh Alang-alang on April 8, 1445.

Ki Gedeng Alang-Alang (1445–1447)

The people of Dukuh Alang-alang chose Danusela as their village chief. He was known as Ki Gedeng Alang-alang. He made Prince Walangsungsang his deputy. But Ki Gedeng Alang-alang died just two years later, in 1447.

Prince Cakrabuana (1447–1479)

After Ki Gedeng Alang-Alang's death, Walangsungsang became the new ruler in 1447. He started a court and took the title Prince Cakrabuana. The port village attracted many new people from different places. It became a busy village renamed Caruban, meaning "mixture." This name showed how many different people lived there. In 1447, records show 346 settlers from various backgrounds, including Sundanese, Javanese, Sumatran, Indian, Arab, and Chinese people.

After a pilgrimage to Mecca, Prince Cakrabuana changed his name to Haji Abdullah Iman. He built a palace called Pakungwati Palace. This palace became his court in Cirebon. This makes him the founder of Cirebon. When his grandfather, Ki Gedeng Tapa, died, Cakrabuana inherited the Singapura settlement. He added it to Cirebon. He used his inheritance to make Pakungwati Palace bigger. His father, King Siliwangi, gave him the title Tumenggung Sri Mangana. Cirebon grew into a busy port. Cakrabuana sent gifts to the Sunda Pajajaran court to show respect.

The early period of Cirebon is often called the Pakungwati period. This refers to the Pakungwati Palace. It was built in a Javanese style, with pavilions and red brick walls. Prince Cakrabuana was the first ruler of Cirebon. He worked hard to spread Islam to the people of Cirebon and West Java.

Meanwhile, Princess Rara Santang also went on a pilgrimage. She met and married Sharif Abdullah from Egypt. She changed her name to Syarifah Mudaim. In 1448, she had a son named Sharif Hidayatullah. In 1470, Sharif Hidayatullah traveled to study in different places like Mecca and Baghdad. Later, he returned to Java. He learned from a scholar named Sunan Ampel and worked in the Demak Sultanate court. Then he came back to Cirebon. He asked his uncle, Prince Cakrabuana, to start an Islamic school in Cirebon.

Cirebon Grows Stronger

Sunan Gunung Jati (1479–1568)

In 1479, Prince Cakrabuana stepped down. His nephew, Sharif Hidayatullah, took over. Sharif Hidayatullah was the son of Princess Rara Santang. He married his cousin, Nyi Mas Pakungwati, Prince Cakrabuana's daughter. He is famous by his later name, Sunan Gunung Jati. He became the first Sultan of Cirebon and lived in Keraton Pakungwati.

In 1482, Sharif Hidayatullah sent a letter to his grandfather, King Siliwangi. The letter said that Cirebon would no longer pay tribute to Pajajaran. Prince Cakrabuana had always paid tribute to show that Sunda was Cirebon's ruler. By refusing to pay, Cirebon declared itself a free and independent state. This independence was marked on April 2, 1482. Today, this date is celebrated as the anniversary of Cirebon Regency.

By 1515, Cirebon was a strong Islamic state. The Portuguese explorer Tomé Pires wrote about it. He said Cirebon was a major port on Java's north coast. It was no longer under the Hindu Sunda Kingdom. He saw Cirebon as an important Muslim state, like Demak.

When Cirebon heard about an alliance between the Portuguese and Sunda in 1522, Gunungjati asked the Demak Sultanate for help. His son, Hasanudin, likely led an attack in 1527. They captured towns like Banten and Sunda Kelapa just as Portuguese ships arrived.

The Sultan of Demak made Hasanudin the king of Banten. He also offered Hasanudin his sister in marriage. This created a new kingdom, the Banten Sultanate. Banten became a province under Cirebon.

Under Gunungjati, Cirebon grew very quickly. It became a powerful kingdom in the area. The busy port city was a center for trade and for learning about Islam. Traders from faraway lands like Arabia and China came to Cirebon. Gunungjati is seen as the founder of the royal families that ruled both Cirebon and Banten. He is also known for spreading Islam in West Java. Scholars from his court taught Islam in many areas, including other coastal ports.

Many foreign traders came to Cirebon. China, especially, had close ties. Gunungjati even married Princess Ong Tien, who was said to be the daughter of the Chinese Emperor. This marriage helped create a strong friendship between China and Cirebon. It was good for trade and business. Princess Ong Tien changed her name to Nyi Rara Semanding. She brought many treasures from China. These treasures are still kept in Cirebon's royal museums today. Because of these close ties, many Chinese people moved to Cirebon. They formed one of the oldest Chinese communities in Java. Chinese influences can be seen in Cirebon's culture, like the famous Cirebon batik megamendung pattern, which looks like Chinese clouds.

As he got older, Gunungjati focused more on teaching Islam. He wanted his second son, Prince Dipati Carbon, to take over. But the prince died young in 1565. Three years later, Gunungjati also died. He was buried in the Gunung Sembung cemetery. People have called him Sunan Gunung Jati ever since.

Fatahillah (1568–1570)

After Gunungjati died, there was no clear successor. General Fatahillah, a trusted officer, took the throne. He had often managed the government when Gunungjati was away teaching Islam. Fatahillah ruled for only two years. He died in 1570 and was buried near Gunungjati.

Panembahan Ratu (1570–1649)

After Fatahillah's death, Gunungjati's great-grandson, Pangeran Mas, became king. He took the title Panembahan Ratu I. He ruled for more than 79 years. During his time, he focused on strengthening Islam. Cirebon became an important center for Islamic learning. Its influence reached the new Mataram Sultanate in Central Java. However, because the king was more interested in being a religious scholar, Cirebon did not try to control Mataram. Mataram then grew much more powerful.

By the 17th century, Mataram became a major power under Sultan Agung. Around 1617, Sultan Agung planned to attack Dutch settlements in Batavia. He asked Panembahan Ratu to be his ally. Cirebon then came under Mataram's influence. Sultan Agung needed support and supplies for his campaign. He asked Cirebon and other West Java leaders for help. However, some Sundanese nobles thought Agung's plan was actually to take their lands. They fought against Mataram. Agung then asked Cirebon to stop these rebellions. In 1618 and 1619, Cirebon defeated the rebels. These areas then came under Mataram's rule.

At this time, the Sultanate of Cirebon included areas like Indramayu, Majalengka, Kuningan, and the modern Cirebon Regency. Even though Cirebon was officially independent, it was largely controlled by Mataram. Mataram's rule brought Javanese culture to the Sundanese people. When Panembahan Ratu died in 1649, his grandson, Panembahan Girilaya, became the next ruler.

Cirebon's Decline

Panembahan Girilaya (1649–1677)

After Panembahan Ratu died in 1649, his grandson, Prince Karim, became the ruler. He was known as Panembahan Ratu II and later as Panembahan Girilaya.

During his rule, Cirebon was caught between two big powers: the Sultanate of Banten to the west and the Mataram Sultanate to the east. Banten thought Cirebon was getting too close to Mataram. Mataram, on the other hand, thought Cirebon was not fully committed to their alliance.

Cirebon had been under Mataram's influence since 1619. In 1650, Mataram asked Cirebon to make Banten submit to Mataram. Banten refused. So, Mataram told Cirebon to attack Banten. Cirebon sent 60 ships, but they were badly defeated. Around this time, Cirebon's relationship with Mataram became very tense. This led to Panembahan Adiningkusuma (Panembahan Girilaya) being killed in Mataram. His two sons, Prince Mertawijaya and Prince Kertawijaya, were held captive in Mataram.

The First Split (1677)

With Panembahan Girilaya gone, Cirebon had no ruler. Prince Wangsakerta, his youngest son, managed things. He was worried about his older brothers being held captive in Mataram. He went to Banten to ask Sultan Ageng Tirtayasa for help. The Sultan of Banten agreed. He saw this as a chance to improve relations with Cirebon. Sultan Ageng Tirtayasa secretly helped a rebellion against Mataram. He managed to rescue the two Cirebon princes.

However, Sultan Ageng Tirtayasa also saw a chance to make Cirebon weaker. He crowned both rescued princes as sultans. Prince Mertawijaya became Sultan Kasepuhan, and Prince Kertawijaya became Sultan Kanoman. By doing this, the Sultan of Banten caused Cirebon to split into several smaller states. Prince Wangsakerta, who had worked for 10 years to free his brothers, received only a small title and no land. This strategy was meant to keep Cirebon weak and prevent it from becoming a threat to Banten or an ally of Mataram.

The first split of Cirebon happened in 1677. All three sons of Panembahan Girilaya became rulers. They were called Sultan Sepuh, Sultan Anom, and Panembahan Cirebon. The title "Sultan" was given by the Sultan of Banten.

- Sultan Kasepuhan: Prince Martawijaya, also known as Sultan Sepuh Abil Makarimi Muhammad Samsudin (1677–1703). He ruled from Keraton Kasepuhan.

- Sultan Kanoman: Prince Kartawijaya, also known as Sultan Anom Abil Makarimi Muhammad Badrudin (1677–1723). He ruled from Keraton Kanoman.

- Panembahan Keprabonan Cirebon: Prince Wangsakerta, also known as Pangeran Abdul Kamil Muhammad Nasarudin or Panembahan Tohpati (1677–1713). He ruled from Keraton Keprabonan.

Sultan Ageng Tirtayasa made the two oldest princes sultans in Banten. Each sultan ruled their own people and lands. Sultan Sepuh ruled the old Pakungwati palace and made it bigger to become Keraton Kasepuhan. Sultan Anom built a new palace, Keraton Kanoman, nearby. Prince Wangsakerta, the youngest, was not made a sultan. He did not inherit land or people. His area became a school for Cirebon thinkers.

Since 1677, each of these three royal lines has had its own sultans or rulers. Usually, the oldest son becomes the next ruler.

The Second Split (1807)

For over a hundred years, the Cirebon royal families continued without major problems. But at the end of Sultan Anom IV's rule (1798–1803), there was a disagreement about who should rule next. One of the princes, Pangeran Raja Kanoman, wanted his own share of the kingdom. He formed his own kingdom called Kesultanan Kacirebonan.

The Dutch East Indies government supported Pangeran Raja Kanoman. They officially appointed him as Sultan Carbon Kacirebonan in 1807. However, the rulers of Keraton Kacirebonan were not allowed to use the title "Sultan." They used "Pangeran" instead. From then on, Cirebon had another ruler. The Sultanate of Cirebon was now split into four royal lines.

The Colonial Era

Since 1619, the Dutch East India Company had a strong base in Batavia. By the 18th century, they also controlled the mountainous region of Priangan. After the Dutch got involved in 1807, they took more control over Cirebon's internal affairs. All four kratons (palaces) lost their real political power. They became protectorates under the Dutch East Indies colonial government.

In 1906 and 1926, all Cirebon kratons officially lost their power over their city and lands. The Dutch government ended the sultanates' authority. They created the Gemeente Cheribon (Cirebon Municipality). The remaining Cirebon sultanates (Kasepuhan, Kanoman, Keprabonan, and Kacirebonan) now only had ceremonial roles.

Cirebon in Modern Indonesia

After Indonesia became independent, each Cirebon sultanate became part of the new republic. The real power was held by local government leaders. The royal families (Kasepuhan, Kanoman, Keprabonan, and Kacirebonan) still have ceremonial roles. They are important cultural symbols. Each royal family still has its own line of kings.

After the fall of President Suharto and the start of Indonesia's democratic era, some people wanted to create a new Cirebon province. This new province would cover the area of the old Cirebon Sultanate. It would be similar to the Special Region of Yogyakarta. However, this idea is still just a proposal. Because of a lack of money and care, all four Cirebon kratons are in poor condition. In 2012, the government planned to restore them.

Cirebon's Culture

In its early years, the sultanate actively spread Islam. Cirebon sent its religious scholars to teach Islam in West Java. Cirebon and Banten are known for bringing Islam to the Sundanese people in West Java and coastal Java. Because Cirebon is located where Javanese and Sundanese cultures meet, its culture shows influences from both. This can be seen in its art, buildings, and language. The Pakungwati Palace, for example, shows the influence of Majapahit architecture. The titles of its officials are also influenced by Javanese court culture.

As a port city, Cirebon attracted people from all over the world. Cirebon's culture is a "coastal Java" culture. It is similar to Banten, Batavia, and Semarang. It has strong influences from Chinese, Arabic-Islamic, and European cultures. Cirebon batik has bright colors and patterns that show Chinese and local influences. The Cirebon batik Megamendung pattern, which looks like Chinese clouds, is a good example of Chinese influence.

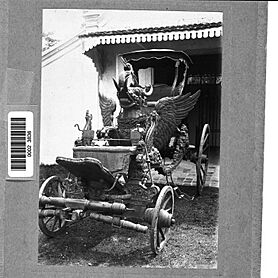

Some of Cirebon's royal symbols tell us about its history and influences. The Cirebon Sultanate's banner is called "Macan Ali" (Ali's panther). It has Arabic writing shaped like a panther or tiger. This shows both Islamic influence and the influence from the Hindu Sundanese King Siliwangi's tiger banner. The royal carriages, like Kasepuhan's Singa Barong and Kanoman's Paksi Naga Liman, combine three animals: an eagle, an elephant, and a dragon. These symbolize Indian Hinduism, Arabic Islam, and Chinese influences. These images are also often seen in Cirebon batik patterns.

The remaining Cirebon Sultanate palaces (Kasepuhan, Kanoman, Kaprabonan, and Kacirebonan) now work as cultural centers. They help preserve Cirebon's unique culture. Each still holds traditional ceremonies and supports Cirebon art. The Topeng Cirebon mask dance, inspired by Javanese stories, is a famous traditional Cirebon dance. Even though the royal families no longer have political power, they are still highly respected by the people of Cirebon.

Important Rulers of Cirebon

Here are some of the key leaders of the Cirebon Sultanate:

- Prince Cakrabuana: 1447–1479. He is seen as the founder of the Cirebon Sultanate.

- Sunan Gunungjati (Sultan Cirebon I): 1479–1568.

- Fatahillah: 1568–1570. He took over when the crown prince died.

- Panembahan Ratu I (Sultan Cirebon II): 1570–1649.

- Panembahan Ratu II (Sultan Cirebon III): 1649–1677.

In 1679, the Sultanate of Cirebon was divided into two main kingdoms, Kasepuhan and Kanoman. This happened because of power struggles among the royal family.

Images for kids

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |