Sunda Kingdom facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Sunda Kingdom

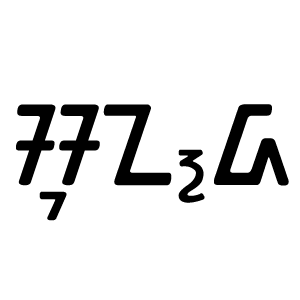

ᮊᮛᮏᮃᮔ᮪ ᮞᮥᮔ᮪ᮓ

Karajaan Sunda |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 669–1579 | |||||||||||||

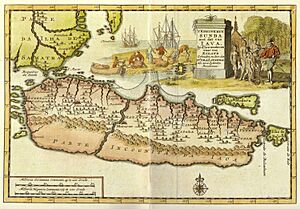

The territory of Sunda Kingdom

|

|||||||||||||

| Capital |

|

||||||||||||

| Common languages | Old Sundanese (main) Sanskrit |

||||||||||||

| Religion | Hinduism Buddhism Sunda Wiwitan |

||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||

| Maharaja | |||||||||||||

|

• 723–732

|

Sanjaya | ||||||||||||

|

• 1371–1475

|

Niskala Wastu Kancana | ||||||||||||

|

• 1482–1521

|

Sri Baduga Maharaja | ||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||

|

• Coronation of king Tarusbawa and change the name from Tarumanagara to Sunda

|

669 | ||||||||||||

| 1579 | |||||||||||||

| Currency | Native gold and silver coins | ||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

| Today part of | Indonesia | ||||||||||||

The Sunda Kingdom (Sundanese:

The Sunda Kingdom was strongest during the rule of King Sri Baduga Maharaja. He reigned from 1482 to 1521. People in Sunda still remember his time as a period of peace and wealth. Old writings like the Bujangga Manik manuscript say the kingdom's eastern border was the Pamali River and the Serayu River in Central Java. Most of what we know about the Sunda Kingdom comes from records from the 1500s. The people were mostly Sundanese, and their main religion was Hinduism.

What Does Sunda Mean?

The name Sunda comes from the old Sanskrit word su-. This word means "goodness" or "having good qualities." For example, suvarna means "good color" and is used for gold. Sunda is also another name for the Hindu god Vishnu. In Sanskrit, Sundara (for males) or Sundari (for females) means "beautiful" or "excellent."

A Dutch geologist named Reinout Willem van Bemmelen thought Sunda came from Shuddha. This Sanskrit word means "white" and "pure." So, Sunda can also mean bright, light, purity, cleanliness, and white.

The name Sunda is also found in Hindu stories about Sunda and Upasunda. These were two powerful brothers who could not be harmed by others. It is not clear if the kingdom's name came from this story.

By the 900s, people from other lands, like Indian explorers and Javanese neighbors, used "Sunda" to describe western Java. An old stone carving from 932 CE, called the Juru Pangambat inscription, confirms this. The Javanese also used the name for their western neighbors, who were sometimes rivals.

In the early 1200s, a Chinese report mentioned the pepper port of Sin-t'o (Sunda). This likely meant the port of Banten or Sunda Kalapa. By the 1400s and 1500s, after King Sri Baduga Maharaja made the kingdom stronger, "Sunda" became the name for the kingdom and its people. The Sunda Strait is named after the Sunda Kingdom because the kingdom once ruled the lands on both sides of the strait.

How We Know About Sunda

People in Sunda have kept the kingdom's stories alive through Pantun. This is an oral tradition where people chant poems about the golden age of Sunda Pajajaran. The legend of Prabu Siliwangi, the most famous king of Sunda, is also part of this tradition.

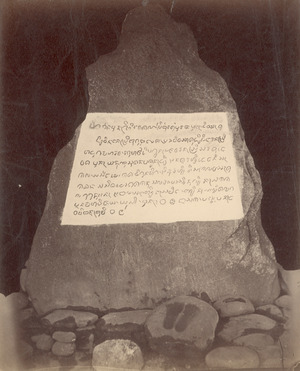

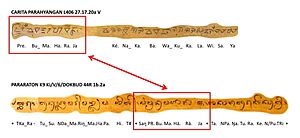

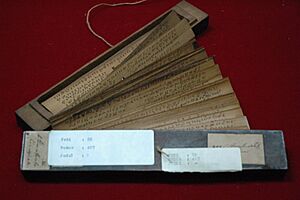

Several stone carvings, called inscriptions, talk about the kingdom. These include Juru Pangambat, Jayabupati, Kawali, and Batutulis. Most of what we know about the Sunda Kingdom comes from writings from the 1400s and 1500s. These include manuscripts like Bujangga Manik, Sanghyang Siksakanda ng Karesian, Carita Parahyangan, and Kidung Sunda.

Local Stories and Records

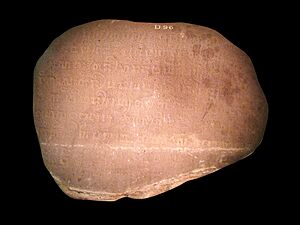

The first time "Sunda" was used for a kingdom was in the Kebon Kopi II inscription from 932 CE. This carving is in the Kawi script but uses the Old Malay language. It says:

This stone remembers the words of Rakryan Juru Pangambat (Royal Hunter), in 854 Saka, that the government's power is returned to the king of Sunda.

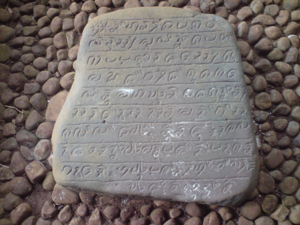

Another record is the Jayabupati inscription. It has 40 lines on four stones found near the Cicatih river in Cibadak, Sukabumi. This carving is also in Kawi script. It says King Jayabhupati of Sunda created a special holy area called Sanghyang Tapak. This inscription is from 1030 CE.

Copper plates from the 1400s also show the Sunda Kingdom existed. One plate says King Rahyang Niskala Wastu Kancana ordered that people in Jayagiri and Sunda Sembawa should not pay taxes. This was because they knew about the Hindu religion and worshipped the gods.

The Bujangga Manik manuscript is a key source about daily life in the Sunda Kingdom in the late 1400s and early 1500s. It describes places, culture, and customs in great detail. The story is about Jaya Pakuan, also called Bujangga Manik. He was a prince but chose to live a simple life as a Hindu holy man. The book tells about his two trips from Pakuan Pajajaran to central and eastern Java. He also visited Bali. The story was written before Islam became widespread in Sunda. It does not have any Arabic words or Islamic ideas.

Chinese Records

Chinese writings also mention the Sunda Kingdom. A report from 1178 to 1225 AD, called Chu-fan-chi, talks about the deep harbor of Sin-t’o (Sunda). It says:

People live all along the shores. They farm, and their houses are on poles. The roofs are made of palm leaves, and the walls are wooden boards tied with rattan. Both men and women wear cotton cloths around their waists. They cut their hair very short. The pepper from this country is small but heavy and better than pepper from Tuban. The country grows pumpkins, sugar cane, bottle gourds, beans, and eggplants. But because there is no strong government, people steal. So, foreign traders rarely go there.

This report says the Sunda Kingdom produced high-quality black pepper. The kingdom was in western Java, near the Sunda Strait. This matches today's Banten, Jakarta, and western West Java. The report also says the port of Sunda was controlled by the Srivijaya kingdom. This port was likely Old Banten, not Sunda Kalapa (today's North Jakarta). Its capital was 10 kilometers inland, near Mount Pulosari.

Another Chinese book from around 1430 AD, “Shun-Feng Hsiang-Sung,” says:

When sailing east from Sunda, along Java's north coast, ships sailed for three watches to reach Kalapa. Then they followed the coast past Tanjung Indramayu, finally sailing to reach Cirebon. Ships from Banten went east along Java's north coast, past Kalapa, past Indramayu head, past Cirebon.

This source suggests the port of Sunda was west of Kalapa, which was later known as the port of Old Banten.

European Records

European explorers, mostly Portuguese from Malacca, also wrote about the Sunda Kingdom. Tomé Pires (1513) mentioned a western Java kingdom that traded with them as Regño de Çumda, meaning "Kingdom of Sunda." Antonio Pigafetta (1522) also wrote about Sunda as a place that produced pepper.

Tomé Pires wrote in his report Suma Oriental (1513–1515):

Some people say the Sunda kingdom covers half of Java island. Others, who are more trusted, say it is a third part of the island and an eighth more. It ends at the Chi Manuk river. This river cuts across the whole island from sea to sea. So, when people of Java describe their country, they say it is bordered on the west by the island of Sunda. People believe that whoever crosses this strait (the Cimanuk river) into the South Sea is carried away by strong currents and cannot return.

The Portuguese report is from later in the kingdom's history, just before it fell to the Sultanate of Banten.

History of the Sunda Kingdom

The Sunda Kingdom's history lasted for almost 900 years, from the 600s to the 1500s. One of the oldest remaining structures is the 7th-century Bojongmenje Hindu temple near Bandung. It is one of the earliest temples in Java, even older than the Dieng temples in Central Java, and is linked to the Sunda Kingdom.

The early history is not very clear. We only have two manuscripts from much later times, like the Carita Parahyangan. We don't know much about its connection to Tarumanagara, an earlier kingdom in western Java. However, the history after the late 1300s is clearer. This is especially true after the reigns of King Wastu Kancana and Sri Baduga Maharaja. This is because there are more historical sources available. These include foreign reports, especially the Portuguese Suma Oriental. There are also several stone inscriptions, like Batutulis, and local writings like Bujangga Manik and Sanghyang Siksakanda ng Karesian.

Early Rulers

According to the Kebon Kopi II inscription from 932 CE, found near Bogor, a skilled hunter named Rakryan Juru Pangambat announced that power was returned to the king of Sunda. This inscription was written in Kawi alphabet but in Old Malay. Some historians think this means the Sunda Kingdom declared its freedom, possibly from Srivijaya.

The Sanghyang Tapak inscription, from 1030 CE, found near Sukabumi, says that King Maharaja Sri Jayabupati created a sacred place called Sanghyang Tapak. The style of this inscription is similar to those from the Mataram kingdom in East Java. This suggests that the Sunda Kingdom might have been influenced by Mataram at that time.

After Sri Jayabupati, no stone inscriptions have been found about the next rulers. We don't have much physical evidence from the 1000s to the 1300s. Most of what we know from this period comes from the Carita Parahyangan manuscript.

A Chinese source from around 1200, Chu-fan-chi, said that Srivijaya still ruled Sumatra, the Malay peninsula, and Sin-to (Sunda). It described the port of Sunda as important and busy. Pepper from Sunda was among the best. People farmed, and their houses were built on wooden poles. However, robbers were a problem. It seems that in the early 1200s, trade by sea was still controlled by Srivijaya.

Golden Age of Sunda

The name Sunda appeared in a Javanese source, the Pararaton. It reported that in 1336, Gajah Mada, a powerful prime minister, made the Palapa oath. He promised to unite the archipelago under Majapahit rule. The Pararaton recorded Gajah Mada saying:

"He, Gajah Mada the Patih Amangkubumi, does not wish to stop his fasting. Gajah Mada: "If (I succeed) in defeating (conquering) Nusantara, (then) I will break my fast. If Gurun, Seram, Tanjung Pura, Haru, Pahang, Dompo, Bali, Sunda, Palembang, Temasek, are all defeated, (then) I will break my fast."

Sunda was one of the kingdoms Gajah Mada wanted to conquer. By the early 1300s, the Sunda Kingdom had become quite wealthy and was involved in international trade.

King Prabu Maharaja

The Carita Parahyangan and Pararaton call him Prěbu Maharaja. He ruled from Kawali Galuh. He died in the Battle of Bubat in 1357. This happened because of a trick by the Majapahit prime minister, Gajah Mada.

Hayam Wuruk, the king of Majapahit, wanted to marry Princess Dyah Pitaloka. She was the daughter of Prabu Maharaja. The Sunda king and his family went to Majapahit for the wedding. They set up camp in Bubat square and waited for the ceremony. However, Gajah Mada saw this as a chance to make Sunda surrender to Majapahit. He insisted the princess be given as a sign of surrender.

The Sunda king was angry and insulted. He decided to cancel the wedding and go home. This led to a fight between the Sunda royal family and the Majapahit army. The Sundanese were outnumbered, and almost all of them died, including the princess. Tradition says Princess Dyah Pitaloka took her own life to protect her country's honor. After his death, Prabu Maharaja was called Prabu Wangi (meaning "King with a pleasant fragrance") because he bravely defended his honor. His successors were later called Siliwangi (meaning "successor of Wangi"). This story is the main part of the book Kidung Sunda, another source from Bali.

Niskala Wastu Kancana's Long Reign

The next king of Sunda was Niskala Wastu Kancana. He was the youngest son of Prabu Maharaja and the younger brother of Princess Dyah Pitaloka, who both died in the Bubat Incident. In 1371, Prince Wastu became king, known as Prabu Raja Wastu Kancana.

One of the Astana Gede inscriptions, from the late 1300s, says the king ordered walls and moats to be built around Kawali city. He also fixed up the Surawisesa palace. These defenses were probably built because of threats from other kingdoms, especially after the Bubat incident made relations with Majapahit very bad. Niskala Wastu then lived in the Kawali palace of Galuh. His rule is remembered as a long time of peace and wealth.

The Kebantenan I copper plate says King Rahyang Niskala Wastu Kancana ordered that people in Jayagiri and Sunda Sembawa should not pay taxes. This was because they knew about the Hindu religion and worshipped the gods.

According to the Batutulis inscription, Rahyang Niskala Wastu Kancana was buried in Nusalarang. The Carita Parahyangan manuscript also says "Prebu Niskala Wastu Kancana surup di Nusalarang ring giri Wanakusumah" (died in Nusalarang on Mount Wanakusumah). At this time, the capital was still in Galuh, specifically in Kawali city.

Ningrat Kancana's Short Rule

Niskala Wastu Kancana's son, called Tohaan di Galuh (Lord of Galuh) in Carita Parahyangan, became king after him. He is mentioned as Hyang Ningrat Kancana in the Kebantenan I inscription and Rahyang Dewa Niskala in the Batutulis inscription.

This new king ruled for only seven years and was then removed from power. Carita Parahyangan says "... kena salah twa(h) bogo(h) ka estri larangan ti kaluaran ..," which means "because of his wrongdoing, he fell in love with a forbidden outsider woman." It is possible this "forbidden outsider woman" was a Muslim, which would show that Islam was present in western Java at that time.

The Batutulis inscription says Rahyang Dewa Niskala was buried in Gunatiga. The Carita Parahyangan supports this, saying Tohaan di Galuh was nu surup di Gunung Tilu' (died or buried in Gunung Tilu, meaning "Three Mountains"). This matches the Gunung Tilu mountain range east of Kuningan town.

Sri Baduga Maharaja's Golden Age

Sang Ratu Jayadewata (ruled 1482 to 1521), also known as Sri Baduga Maharaja, was the grandson of Prabu Wastu Kancana. Jayadewata is often linked to the popular character Prabu Siliwangi in Sundanese oral stories.

King Jayadewata moved the government from Kawali back to Pakuan in 1482. It is not clear why the capital moved west. It might have been a move to keep the capital safe from the growing Muslim power of the Demak Sultanate in Central Java. By 1482, according to a Cirebon history, Cirebon declared its independence from Sunda. It no longer sent payments to the Sunda court.

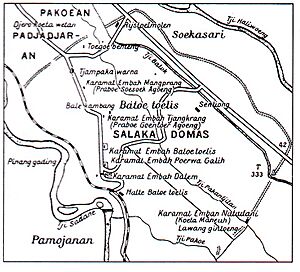

According to the Batutulis inscription, Sri Baduga Maharaja built defensive moats around Pakuan Pajajaran. He also built sacred mounds, created huts, and set up the holy Samya forest. This forest was a source of wood for offerings. He also built the artificial lake Talaga Rena Mahawijaya, which was likely a water reservoir. There was a good road to Sunda Kalapa (today's Jakarta), which was the most important harbor of the Sunda kingdom. When Tomé Pires visited Pakuan, Sri Baduga Maharaja was the king of Sunda.

King Jayadewata's rule is called the golden age for the Sundanese people. The kingdom became stronger and ruled all of western Java. It was also a time of great wealth. This came from good farming and the busy pepper trade in the area. However, this time of great wealth also marked the start of the Sunda kingdom's decline.

Decline of the Kingdom

During King Jayadewata's rule, some Sunda people had already become Muslims. Tomé Pires reported in 1513 that many Muslims lived in the port of Cimanuk (today Indramayu), the easternmost port of Sunda Kingdom. The port of Cirebon, just east of Cimanuk, was already a Muslim port ruled by Javanese at that time.

These new converts were probably the people mentioned in Carita Parahyangan as "those who felt no peace because of having strayed from Sanghyang Siksa." Still, at this time, Islamic influence had not yet reached the capital inland. Carita Parahyangan said that the capital was "safe from rough/coarse enemy, (as well as) soft/subtle enemy." "Coarse enemy" meant an invading army, while "subtle enemy" meant the spread of a new religion that could change the kingdom's spiritual order.

The kingdom was worried about the growing power of the Islamic Sultanate of Demak. This sultanate finally destroyed Daha, the last part of the Hindu Majapahit kingdom, in 1527. After this, only Blambangan in eastern Java and Sunda in western Java remained Hindu kingdoms. Meanwhile, in Sunda, Muslim influences began to spread.

Rise of Muslim Cirebon and Banten

The Bujangga Manik manuscript, written around the late 1400s, said the eastern border of the Sunda Kingdom was the Cipamali river in today's Brebes. However, the Portuguese Suma Oriental in 1513 reported that the eastern border was at the port of Chemano (Cimanuk), the mouth of the Manuk River. This means that between 1450 and 1513, the kingdom lost control of the area around Cirebon, between Brebes and Indramayu. This shows that Muslim Javanese people from the coast were moving west into what was once Sundanese land. The Demak Sultanate supported the rise of Cirebon.

Most details about the Sunda Kingdom and its relationship with the rising Cirebon Sultanate come from the Purwaka Caruban Nagari. This Cirebon history claims Cirebon as the true successor of the Sunda Kingdom.

According to Purwaka Caruban Nagari, a Sunda king, Prabu Siliwangi, married Nyai Subang Larang. She was the daughter of Ki Gedeng Tapa, the port master of Muara Jati (today Cirebon). They had three children: Prince Walangsungsang, Princess Rara Santang, and Prince Kian Santang. Even though Prince Walangsungsang was the king's first son, he did not become crown prince. This was because his mother, Nyai Subang Larang, was not the main queen. Another reason was that he became a Muslim, possibly influenced by his mother. In the 1500s in western Java, the main religions were Hinduism, Sundanese ancestral religion, and Buddhism. His half-brother, Prabuwisesa, the king's son from his third wife, was chosen as the crown prince.

Walangsungsang later moved to a settlement called Dukuh Alang-alang in 1445. After Ki Gedeng Alang-Alang died in 1447, Walangsungsang became the ruler of the town. He set up a court and took the new title Prince Cakrabuana. King Siliwangi sent his envoys to give Prince Carkrabuana the title Tumenggung Sri Mangana. The settlement, now called Cirebon, grew into a busy port. Cakrabuana was still loyal to his father and sent payments to the main Sunda court. At that time, Cirebon was still a small state within the Sunda Kingdom.

In 1479, Cakrabuana was followed by his nephew, Sharif Hidayatullah. He was the son of Cakrabuana's sister, Nyai Rara Santang. He married his cousin, Nyi Mas Pakungwati, Cakrabuana's daughter. He is famously known as Sunan Gunungjati. On April 2, 1482, Sunan Gunungjati declared that Cirebon would no longer send payments to Pajajaran. This marked the start of the Sultanate of Cirebon as independent from Sunda Pajajaran.

The king described in Purwaka Caruban Nagari as Prabu Siliwangi matches the historical figure of Dewa Niskala or Ningrat Kancana. He was called Lord of Galuh in Carita Parahyangan. Tohaan di Galuh was the son and heir of Niskala Wastu Kancana.

The pressure from Muslim states on Java's coast made the king of Sunda, Sri Baduga Maharaja, ask for help from the Portuguese in Malacca. In 1512 and again in 1521, he sent his son, Crown Prince Surawisesa, to Malacca. He asked the Portuguese to sign a treaty to trade pepper and build a fort at his main port of Sunda Kalapa. Sunan Gunung Jati's son later also started the Sultanate of Banten. This sultanate later became a threat to the Hindu Sunda Kingdom.

Treaty with the Portuguese (1522)

After Sri Baduga Maharaja died in 1521, the next king, Prabu Surawisesa Jayaperkosa, faced threats from the Cirebon and Demak sultanates. To deal with this, Surawisesa, who ruled from 1521 to 1535, made a treaty with the Portuguese from Malacca. The Portuguese would build a warehouse and fort at Sunda Kelapa. In return, they would get protection from the Islamic sultanates.

By 1522, the Portuguese wanted to work with the King of Sunda to get access to his valuable pepper trade. The commander of Malacca sent a ship to Sunda Kalapa with gifts for the king. Two old writings describe this treaty in detail. One is the original Portuguese document from 1522. The other is a report by João de Barros in his book Da Ásia.

The king welcomed them warmly. The crown prince had become King Prabu Surawisesa. This Sunda ruler agreed to be friends with the King of Portugal. He allowed them to build a fort at the mouth of the Ciliwung River. There, the Portuguese could load as much pepper as they wanted. He also promised to give 1,000 sacks of pepper to the Portuguese king each year, starting when the fort was built. The agreement was written in two copies and signed. In 1522, Henrique Leme and his group, along with the King of Sunda's representatives, put up a stone pillar at the mouth of the Ciliwung River to remember the treaty.

The Fall of Sunda Kalapa

This trade and defense treaty failed badly. The Portuguese did not build the fort in Kalapa as they promised. This delay was caused by problems in Goa. To make things worse, in 1527, Fatahillah, a military leader from Demak, captured the Sunda Kalapa harbor just before the Portuguese returned.

Fatahillah's army, made of troops from Cirebon and Demak, took Sunda Kalapa. The Sunda officials in the port were defeated. The harbor chief, his family, the royal minister, and all the people working in the harbor were killed. The port city was completely destroyed. Sundanese soldiers sent from Pakuan were too weak and retreated. The Sunda Kingdom had lost its most important port. Sunda Kalapa was then renamed Jayakarta by its Muslim conqueror.

Thirty Portuguese sailors, whose ship was wrecked by storms, swam to the beach at Kalapa. They were killed by Fatahillah's men. The Portuguese realized the government had changed when they were not allowed to land. Since they were too weak to fight, they sailed back to Malacca. A year later, a second attempt failed because sailors refused to work, angry about not being paid.

Because the Portuguese failed to help, Sunda had to fight for its own survival. Carita Parahyangan says that during his 14 years as king (1521–1535), King Sang Hyang (Surawisesa) fought in 15 battles. He won all of them, pushing back the Muslim forces from Cirebon and Demak. He fought in Kalapa, Tanjung, Ancol Kiji, Wahanten Girang, Simpang, Gunung Batu, Saung Agung, Rumbut, Gunung, Gunung Banjar, Padang, Panggoakan, Muntur, Hanum, Pagerwesi, and Medangkahyangan.

The war between Cirebon-Demak forces and the Sunda kingdom lasted almost five years. The king lost thousands of his soldiers. During this war, after Sunda Kalapa, the Sunda Kingdom also lost the Port of Banten. Sunan Gunungjati of Cirebon later made his son, Hasanuddin, the king of Banten. The Sultan of Demak then offered Hasanudin his sister's hand in marriage. Banten became the capital of this new sultanate, controlled by the Sultanate of Cirebon. Finally, in 1531, King Surawisesa of Sunda and Syarif Hidayatullah of Cirebon made a peace treaty.

After this great defeat and the loss of his two most important ports, Prabu Surawisesa set up the Batutulis inscription in 1533. This was to honor his late father. He probably hoped to get guidance and protection from his ancestors against the strong Muslim enemy. Because of the ongoing battles, he often could not stay in his palace in Pakuan Pajajaran.

Last Kings and the End of Sunda

Prabu Ratu Dewata, also known as Sang Ratu Jaya Dewata, became king after Prabu Surawisesa. He was not Surawisesa's son. His rule from 1535 to 1543 was difficult and full of problems. Islamic forces from Cirebon and Banten tried many times to capture the capital, Dayeuh Pakuan.

During Ratu Dewata's rule, the Carita Parahyangan reported several disasters. There was a sudden attack, and many enemies destroyed the city. A big battle happened in the main yard. In this battle, noble princes were killed. The chaos spread across the kingdom. Attacks also happened in Ciranjang and Sumedang. Another terrible event was the killing of the rishis, hermits, and Hindu priests who lived in holy places. It was said that the Hindu priests and hermits of mandala Jayagiri were captured and drowned in the sea. These attacks were likely from the Muslim states of Banten or Cirebon. This was a terrible blow to the spiritual heart of the Sundanese Hindu community.

The king, Prabu Ratu Dewata, could not control the kingdom. Instead of doing his duty to keep order, he became a Raja Pandita (priestly king). He spent his time in religious rituals, seemingly hoping for help from the gods. By this time, the Sunda Kingdom was isolated and only controlled inland areas.

The last kings of Sunda were known for being unable to rule well. King Ratu Sakti, who ruled from 1543 to 1551, was known as a cruel king.

The next king, Nilakendra, also called Tohaan di Majaya, ruled from 1551 to 1567. He was also not a good ruler. Instead of doing his kingly duties, he spent the kingdom's money on making the palace beautiful and enjoying luxuries.

Because of ongoing battles, Tohaan di Majaya could not even stay in his newly renovated palace. The last kings of Sunda could no longer live in Pakuan Pajajaran. In the 1550s, Hasanuddin, the sultan of Banten, successfully attacked Dayeuh Pakuan. He captured and destroyed the capital.

The remaining Sunda royals, nobles, and common people fled the fallen city. They went to the wild mountains. After Pakuan Pajajaran fell, the royal items of the Sunda Kingdom were taken to the eastern state of Sumedang Larang. Among these items was Makuta Binokasih Sanghyang Paké, the royal crown of Sunda. So, members of the Sunda dynasty started a smaller kingdom called Sumedang Larang. Sundanese nobles would survive there for a few more centuries until the Mataram Sultanate conquered it in the 1600s.

From 1567 to 1579, under the last king Raja Mulya, also known as Prabu Surya Kencana, the kingdom became much weaker. In Carita Parahyangan, his name is Nusiya Mulya. He ruled further inland in Pulasari, near Pandeglang. The kingdom fell apart, especially after 1576, due to constant pressure from Banten. It finally collapsed completely in 1579. After that, the Sultanate of Banten took over most of the former Sunda Kingdom's land. This ended a thousand years of Hindu-Buddhist civilization in West Java. By this time, Java had become more and more Islamic. Only the Blambangan kingdom on the eastern edge was the last Hindu kingdom in Java, until it fell in the early 1700s.

Capital Cities of Sunda

Throughout Sunda's history, the main center of power often moved. It shifted between the Western Priangan region, known as "Sunda," and the Eastern Priangan region, known as "Galuh." These two important places are near modern Bogor city and the town of Ciamis. The two most important capitals were Pakuan Pajajaran, the capital of Sunda, and Kawali, the capital of Galuh.

Kawali: An Eastern Capital

The capital of the Galuh Kingdom in the eastern Priangan region moved several times. In earlier times, the capital was near the Karang Kamulyan site, by the Citanduy river. By the early 1300s, the capital moved further northwest, to the area now called Astana Gede. This is near the current town of Kawali, Ciamis Regency. The city was on the eastern slope of Mount Sawal, near the source of the Citanduy river. A Kawali inscription was found here. Tradition says the palace in Kawali was called Surawisesa. King Niskala Wastu Kancana expanded and fixed it. Kawali was the kingdom's capital for many years until Sri Baduga Maharaja moved the government back to Pakuan in 1482.

Pakuan Pajajaran: The Main Capital

After the fall of Tarumanagara in the 600s, King Tarusbawa built a new capital city inland. It was near the source of the Cipakancilan river, in today's Bogor. According to Carita Parahyangan, a manuscript from the 1400s or 1500s, King Tarusbawa was simply called Tohaan (Lord/King) of Sunda. He was the ancestor of many Sunda kings who ruled until 723. Pakuan was the capital of Sunda during the rule of several kings. The court then moved to Kawali until Sri Baduga Maharaja moved it back to Pakuan in 1482.

The city was always lived in since at least the 900s. But it did not become politically important until King Jayadewata made it the royal capital of the Sunda kingdom in the 1400s. In 1513, the first European visitor, Tomé Pires, a Portuguese envoy, came to the city. His report said the city of Daio (Dayeuh is a Sundanese word for "capital city") was a great city. It had about 50,000 people.

Tradition says King Jayadewata ruled fairly from his beautiful palace, Sri Bima Punta Narayana Madura Suradipati, in Pakuan Pajajaran. His rule is celebrated as the golden age for Sundanese people.

After King Jayadewata (Sri Baduga Maharaja), Pakuan Pajajaran remained the royal capital for several generations. Dayeuh Pakuan Pajajaran was the capital of the Sunda Kingdom for almost 100 years (1482 – 1579). It was then destroyed by the Sultanate of Banten in 1579.

Pakuan, the capital city, was located between two parallel rivers, Ciliwung and Cisadane. Because of this, it was called Pajajaran (meaning "place laid between two parallel things") or Pakuan Pajajaran. Although old local and European records called the kingdom in western Java island the Sunda Kingdom, the Sundanese, especially after the the Sultanate of Banten and Cirebon were established, called the kingdom (without the coastal sultanates) the "Pakuan Pajajaran" Kingdom, or simply the Pakuan Kingdom or the Pajajaran Kingdom. The name Pajajaran is more familiar to people in West Java and the Javanese of the Mataram region (today's Yogyakarta and Solo).

How Sunda Was Governed and Its Economy

Government and Administration

Many historical records, including manuscripts, stone carvings, and foreign reports from China and Portugal, all call "Sunda" a kingdom. The terms "Pakuan" and "Pajajaran" or "Dayeuh" refer to its capital, which is today's Bogor. Proof of the kingdom's government was found in the Sanghyang Tapak inscription from 1030 CE. It mentions Prahajyan Suṇḍa (Sunda Kingdom) and calls Sri Jayabhupati haji ri Suṇḍa (the king of Sunda).

From studying the 1300s inscriptions in Astana Gede, historians believe the Sunda Kingdom's government followed the idea of Tri Tangtu di Buana. This means power was shared among three groups: Prebu (the king), Rama (village chiefs or regional elders), and Resi (holy priests who held religious power).

According to Tomé Pires (1513), the Sunda kingdom was ruled by a main raja (king). The right to the throne passed from father to son. However, if a king had no male heir, the next ruler was chosen from the lesser kings. These were rulers of regional towns or provinces. These lesser kings were called Tohaan (lord) and acted as local governors. Most of them were related to the main king, meaning they were part of the same royal family.

Much of what we know about the social order and government structure comes from the Sundanese manuscript Sanghyang siksakanda ng karesian, written around 1518. It describes a system of devotion:

According to Carita Parahyangan, all regional rulers (governors), village chiefs, government officials, and Hindu priests had to visit the capital every year. They would pay respect, taxes, or tribute to the court. Some parts of this manuscript say: "..., ti Kandangwesi pamwat siya ka Pakwan..." ("... from Kandangwesi the tribute was sent to Pakuan"), "..., anaking sang Prebu Rama, Resi samadaya sarerea siya marek ka Pakwan unggal tahun..." ("... my son the chief of the village, the rishis together all paid a visit to Pakuan every years").

Economy and Trade

The Sunda kingdom's economy relied on agriculture, especially growing rice. This is shown in Sundanese culture and their yearly ceremonies for planting crops and the Seren Taun rice harvest festival. The harvest ceremony also allowed the king's officials to collect taxes in the form of rice. This rice was stored in the state's Leuit (rice barn).

According to Siksakanda ng Karesian, Sundanese farmers during the Sunda Kingdom era knew about sawah, or wet-field rice cultivation. However, the most common way of growing rice in the kingdom seemed to be ladang, or dry-field rice. This is a simpler way of farming that does not need a complex social system to support it. This fits with the geography of West Java, which has many central plateaus. In contrast, Central and East Java have river valleys between volcanoes. As a result, West Java was less populated at that time. It had settlements, villages, or small communities that were quite isolated in highland valleys. This made it hard for the kingdom's central government to control them directly.

The kingdom was also famous as the world's main producer of high-quality pepper. The kingdom was part of a spice trade network in the islands. The ports of Sunda were involved in international trade in the region.

In Suma Oriental, written from 1512-1515, Tomé Pires, a Portuguese explorer, wrote about the ports of Sunda:

First the king of Çumda (Sunda) with his great city of Dayo, the town and lands and port of Bantam, the port of Pomdam (Pontang), the port of Cheguide (Cigede), the port of Tamgaram (Tangerang), the port of Calapa (Kelapa), and the port of Chemano (Chi Manuk or Cimanuk), this is Sunda, because the river of Chi Manuk is the limit of both kingdoms.

Another Portuguese explorer, Diogo do Couto, wrote that the Sunda kingdom was thriving and rich. It was located between Java and Sumatra, separated by the Sunda Strait. Many islands were along the coast of this kingdom within the strait. Bantam was about in the middle. All the islands had good timber but little water. A small island called Macar, at the entrance of Sunda Strait, was said to have much gold.

He also noted that the main ports of the Sunda kingdom were Banten, Ache, and Chacatara (Jakarta). These ports received twenty ships from China each year. These ships carried 8,000 bahars (about 3,000,000 kg) of pepper that the kingdom produced.

Bantam was located at 6° south latitude, in the middle of a bay. The town was about 850 fathoms long, and the seaport extended about 400. A river that could fit large ships flowed through the middle of the town. A smaller branch of this river allowed boats and small vessels.

There was a brick fort with walls seven palms thick. It had wooden defenses with two levels of cannons. The anchorage was good, with a muddy or sandy bottom and a depth of two to six fathoms.

Culture and Society

Religion and Beliefs

Hinduism was one of the first religions to influence West Java, starting with the Tarumanagara kingdom around the early 400s CE. West Java was one of the earliest places in Indonesia to be influenced by Indian culture. This also marked the start of Indonesia's historical period, as it produced the earliest inscriptions in Java. As Tarumanagara's successor, the Sunda Kingdom continued to be influenced by Hindu civilization.

The culture of the Sunda kingdom mixed Hinduism with Sunda Wiwitan. This was a local shamanism belief. There were also signs of Buddhism. Several old megalithic sites, like Cipari in Kuningan and the Pangguyangan menhir and stepped pyramid in Cisolok, Sukabumi, show that local shamanic beliefs and dynamism existed alongside Hinduism and Buddhism. The native belief, Sunda Wiwitan, still exists today among the Baduy or Kanekes people, who resist Islam and other foreign influences.

The Cangkuang Hindu temple in Leles, Garut, from the 700s, was dedicated to Shiva and built during the Galuh kingdom. Buddhist influence came to West Java through the Srivijaya conquest. This empire controlled West Java until the 1000s. The brick stupas in Batujaya show Buddhist influence in West Java, while nearby Cibuaya sites show Hindu influence.

The manuscript Carita Parahyangan clearly shows Hindu spirituality in Sunda Kingdom society. This manuscript begins with a legendary character named Sang Resi Guru, who had a son named Rajaputra. The manuscript was written by a Hindu scholar and uses Hindu ideas. The Hindu gods, such as Brahma, Vishnu, Mahesvara, Rudra, Sadasiva, Yama, Varuna, Kuvera, Indra, and Besravaka, were also mentioned in the old Sundanese manuscript of Sewakadharma, or Serat Dewabuda, from 1435 CE.

The Sundanese manuscript of spiritual guidance, the Sanghyang Siksakanda ng Karesian, also shows Hindu religious views. However, it seems to be mixed with some Buddhist spirituality. It says: " ... ini na lakukeuneun, talatah sang sadu jati. Hongkara namo Sewaya, sembah ing hulun di Sanghyang Panca Tatagata; panca ngaran ing lima, tata ma ngaran ing sabda, gata ma ngaran ing raga, ya eta ma pahayueun sareanana .., ", meaning " ... this must be done, the true message of the good-hearted. Blessed (should be) in the name of Shiva. Worship the servant to Sanghyang Panca Tatagata (Buddha), panca means five, tata means words, gata means body, yes, that is for the good of all."

During the Sunda Kingdom period, not many archaeological findings or records give full details about the people's religions. Still, some interesting things suggest that Hinduism, Buddhism, and local beliefs were combined. This is shown by the respect for the Hyang figure, who was seen as having a higher status than Hindu-Buddhist gods. The Sanghyang Siksakanda Ng Karesian manuscript (1518) says: "...mangkubumi bakti di ratu, ratu bakti di dewata, dewata bakti di hyang...", which means "...governor submits to the king, king submits to the gods, and gods submit to hyang..."

Ancient Sundanese society did not build temples with detailed carvings like those built by the Javanese in central and east Java. Also, their statues, like Shiva from Cangkuang temple and Ganesha from Karang Kamulyan, were very simple. They almost looked like primitive stone carvings. This suggests that Hinduism and Buddhism were not fully adopted by the ancient Sundanese people. They might have still followed their own traditional ancestral beliefs.

Art and Daily Life

The culture of the Sunda kingdom focused on farming, especially growing rice. Nyi Pohaci Sanghyang Asri, the goddess of rice, was seen as the main goddess in Sundanese beliefs. Priests were in charge of religious ceremonies. The king and his people took part in yearly ceremonies and festivals, such as blessing rice seeds and the harvest festival. The yearly Seren Taun rice harvest festival is still practiced today in traditional Sundanese communities.

According to the Bujangga Manik manuscript, the court culture of the Sunda palace and its nobles in Pakuan Pajajaran was very refined. However, no parts of the palace or buildings remain in the former capital. This is probably because they were made of wood and decayed over hundreds of years.

Portuguese sources give us a look into the culture and customs of the Sunda kingdom. In his report “Suma Oriental (1512–1515),” Tomé Pires wrote:

The Sunda kingdom is very rich. The land of Sunda has as many as four thousand horses that come there from Priaman (Sumatera) and other islands to be sold. It has up to forty elephants; these are for the king’s display. A lower quality gold, of six carats, is found. There is a lot of tamarind that the natives use for vinegar.

The city where the king spends most of the year is the great city of Dayo. The city has well-built houses of palm leaf and wood. They say that the king’s house has three hundred and thirty wooden pillars as thick as a wine barrel, and five fathoms (8 m) high, and beautiful timber work on top of the pillars, and a very well-built house. The city is two days journey from the chief port, which is called Kalapa.

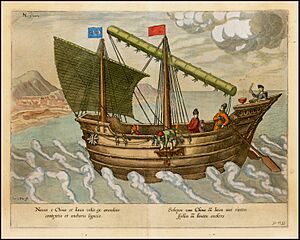

The people of the sea coast get along well with the merchants in the land. They are used to trading. These people of Sunda often come to Malacca to trade. They bring cargo lancharas, ships of a hundred and fifty tons. Sunda has up to six junks and many lancharas of the Sunda kind, with masts like a crane, and steps between each so that they are easy to navigate.

The people of Sunda were said to be honest. They, along with the great city of Dayo, the town and lands and port of Bantam, the port of Pontang, the port of Cheguide, the port of Tangaram, the Port of Tangaram, the port of Calapa, and the port of Chi Manuk, were fairly governed. The king was a great sportsman and hunter. The kingdom passed from father to son. The women were beautiful, and noblewomen were pure. This was not always true for women of lower classes. There were places like monasteries for women. Noble families would send their daughters there if they could not arrange a marriage for them as they wished. Married women, when their husband died, had to die with them to keep their honor. If they were afraid of death, they would go to these monasteries. The people were not very warlike. They were very devoted to their idols. They liked fancy weapons, decorated with gold and inlaid work. Their daggers (krises) were gilded, as were the tips of their spears.

Sunda's Relationships with Other Powers

The Sunda Kingdom is often seen as the kingdom that came after Tarumanagara. Tarumanagara also thrived in the same area of Western Java. It seems that in its early history, around the 900s to 1000s, the Sunda Kingdom was caught between two powerful groups. These were the Malay Srivijaya in Sumatra to the west and its Javanese neighbor to the east.

Early in its history, the kingdom seemed to be under the control of the Srivijaya kingdom. By the 900s, the kingdom seemed to break free. This is stated in the Rakryan Juru Pangambat inscription (932 CE). However, according to the Chinese Song Dynasty book Zhu Fan Zhi, written around 1225, Sin-t'o (Sunda) was still one of Srivijaya's 15 controlled areas.

The Kingdom of Sunda had relationships with its eastern neighbor, the various Javanese kingdoms. This was from the time of the Mataram kingdom in the 700s, all the way to Majapahit in the 1300s and Demak in the 1500s. The famous hero, King Sanjaya of Mataram, known as the Javanese Mataram King mentioned in the Canggal inscription (732), is also mentioned in the Sundanese manuscript Carita Parahyangan. It says he had roots in the Sunda Kingdom.

The Sanghyang Tapak inscription (1030) shows Javanese cultural influence. The style of writing, letters, language, and the king's title are similar to royal names in the East Javanese Mataram court. However, the relationships might not have been very peaceful. An 11th-century East Javanese inscription, Horren inscription, mentioned çatru Sunda. This means the village of Horren was attacked by "the enemy (from) Sunda."

The relationship between the Sundanese and Javanese kingdoms became very bad. A terrible event happened in Bubat square in Majapahit in 1357. All of the Sundanese royal party were killed, including the Sunda king Prabu Maharaja and Princess Tohaan Dyah Pitaloka Citraresmi. This tragedy severely hurt the relationship between the two kingdoms. It led to hostility for many years, and things never returned to normal.

The main enemies of the Hindu Sunda Kingdom were the Islamic states on Java's northern coast. These were the Demak, Cirebon, and later the Banten Sultanate. To protect the kingdom's government and spiritual order, and its economic interests against these Muslim Javanese states, King Sang Ratu Jayadewata asked for help from the Portuguese in Malacca.

The Sunda Kingdom is known as one of the first states in Southeast Asia to have diplomatic relations with a European nation. The Luso-Sundanese padrão (1522) is a stone pillar that remembers a treaty between the kingdoms of Portugal (based in Malacca) and Sunda. The treaty was for a pepper trade agreement and a political alliance. It was against their common enemies: the Islamic Demak and Cirebon.

Legacy of the Sunda Kingdom

Even though the Sunda Kingdom left few physical remains, it is still a part of Sundanese culture. Its stories are kept alive through the Pantun oral tradition, which involves chanting poetic verses.

According to tradition, the Sunda Kingdom under its legendary king, Prabu Siliwangi, is remembered as a time of wealth and glory for the Sundanese people. It is a source of historical identity and pride for the Sundanese, much like Majapahit is for the Javanese people. A pantun that mentions the Sunda Kingdom (often called Pakuan or Pajajaran) says:

Talung-talung keur pajajaran. Jaman keur aya keneh kuwerabekti. Jaman guru bumi dipusti-pusti. Jaman leungit tangtu eusina metu. Euweuh anu tani kudu ngijon. Euweuh anu tani nandonkeun karang. Euweuh anu tani paeh ku jenkel. Euweuh anu tani modar ku lapar

(Pantun Bogor: Kujang di Hanjuang siang, Sutaarga 1984:47)

Translation: It was better during the Pajajaran era, when Kuwera (the god of wealth) was still respected. The era when the earth guru was still honored. The lost era when the true meaning of teaching was given. No farmer had to take loans. No farmer had to sell their lands. No farmer died in vain. No farmer died from hunger.

Dinegara Pakuan sarugih. Murah sandang sarta murah pangan. Ku sakabeh geus loba pare. Berekahna Dewa Guru anu matak kabeh sarugih. Malah ka nagri lain geus kakocap manjur. Dewa Guru miwarangan ka Ki Semar: "maneh Semar geura Indit, leumpangan ka nagri pakuan!" (Wawacan Sulanjana: Plyte 1907:88)

Translation: In the prosperous kingdom of Pakuan, people had plenty of food and clothing. Rice was abundant. The blessing of Dewa Guru was on the land, so everyone was rich. The land's fame spread to other lands. Dewa Guru ordered Ki Semar: "Semar, go now, travel to the kingdom of Pakuan!"

Several streets in major Indonesian cities, especially in West Java, are named after Sundanese kings and the Sunda Kingdom. Examples include Jalan Sunda in Jakarta and Bandung, Jalan Pajajaran in Bogor and Bandung, and Jalan Siliwangi and Niskala Wastu Kancana in Bandung. Padjadjaran University in Bandung was named after Pakuan Pajajaran, the capital and popular name for the Sunda Kingdom. The TNI Siliwangi Military Division and Siliwangi Stadium were named after King Siliwangi, the famous king of Sunda. The West Java state museum, Sri Baduga Museum in Bandung, is named after King Sri Baduga Maharaja.

List of Sunda Kingdom Rulers

| Period | King's Name | Ruled Over | Capital | Source (Inscription or Manuscript) | Key Events |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 709 – 716 | Sena/Bratasena | Galuh | Galuh | Carita Parahyangan | |

| 716 – 723 | Purbasora | Galuh | Galuh | Carita Parahyangan | Purbasora, Wretikandayun's grandson, rebelled against Sena and took the throne of Galuh in 716. |

| 723 – 732 | Sanjaya/Harisdarma/

Rakeyan Jamri |

Sunda, Galuh, and Mataram | Pakuan | Canggal, Carita Parahyangan | Sanjaya, son of Sena's sister, married Tarusbawa's daughter and became king of Sunda. He took revenge for Sena against Purbasora in Galuh. Sanjaya later established the Sanjaya dynasty and Mataram Kingdom in central Java. |

| 1030–1042 | Prabu Detya Maharaja Sri Jayabupati | Sunda and Galuh | Pakuan | Jayabupati | Son-in-law of King Dharmawangsa of Mataram. Declared independence from Srivijaya. Established the sacred place of Sanghyang Tapak. |

| 1175–1297 | Prabu Guru Dharmasiksa | Sunda and Galuh | Saunggalah,

Pakuan |

Carita Parahyangan | His son, Rakeyan Jayadharma, married a princess from Singhasari. Their son, Wijaya, later started Majapahit. |

| 1340–1350 | Prabu Ragamulya Luhurprabhawa/

Aki Kolot |

Sunda and Galuh | Kawali | Carita Parahyangan | |

| 1350–1357 | Prabu Maharaja Lingga Buana/

Prabu Wangi |

Sunda and Galuh | Kawali | Pararaton, Carita Parahyangan, Kidung Sunda | His daughter, Dyah Pitaloka, was to marry King Hayam Wuruk of Majapahit. However, in the Battle of Bubat (1357), the Sunda king, princess, and most of the royal family died. Gajah Mada was blamed for this event. |

| 1357–1371 | Mangkubumi Suradipati/

Prabu Bunisora |

Sunda and Galuh | Kawali | Carita Parahyangan | Mangkubumi Suradipati ruled for a time because the crown prince, Niskala Wastu Kancana, was still a child. |

| 1371–1475 | Prabu Raja Wastu/

Niskala Wastu Kancana/ Sang Mokteng Nusalarang |

Sunda and Galuh | Kawali | Kawali inscription, Carita Parahyangan | The kingdom became wealthy under Niskala Wastu Kancana's long rule. He later divided Sunda and Galuh between his two sons. |

| 1475–1482 | Prabu Susuk Tunggal | Sunda | Pakuan | Carita Parahyangan | Sunda and Galuh became two equal kingdoms. |

| 1475–1482 | Ningrat Kancana/

Prabu Dewa Niskala |

Galuh | Kawali | Carita Parahyangan | Sunda and Galuh became two equal kingdoms. |

| 1482–1521 | Sri Baduga Maharaja/

Ratu Jayadewata |

Sunda and Galuh | Pakuan | Carita Parahyangan | Moved the capital back to Pakuan. The kingdom became strong and enjoyed peace, wealth, and stability. His rule is often called the "golden age" of Pajajaran. |

| 1521–1535 | Prabu Surawisesa Jayaperkosa/

Ratu Sang Hiang |

Sunda and Galuh | Pakuan | Batutulis, Carita Parahyangan, Luso Sundanese Treaty, Padrão | Asked for help from the Portuguese in Malacca in 1522 against the Sultanate of Demak. The treaty failed, and the Sunda Kingdom lost Sunda Kelapa to Fatahillah's forces. The Batu Tulis inscription was made in 1533 to honor his great father. |

| 1535–1543 | Ratu Dewata/

Sang Ratu Jaya Dewata |

Sunda and Galuh | Pakuan | Carita Parahyangan | The kingdom quickly declined and lost most of its land to Cirebon and Banten. |

| 1543–1551 | Ratu Sakti | Sunda and Galuh | Pakuan | Carita Parahyangan | The kingdom grew weaker under pressure from the Sultanate of Banten. |

| 1551–1567 | Nilakendra/

Tohaan di Majaya |

Sunda | Pakuan, Pulasari | Carita Parahyangan | Pakuan fell to the Sultanate of Banten invasion. |

| 1567–1579 | Raja Mulya/

Prabu Surya Kencana |

Sunda | Pulasari | Carita Parahyangan | The king lived in Pulasari, Pandeglang. The kingdom finally collapsed in 1576 under pressure from the Sultanate of Banten. |

See also

- Hinduism in Java

- History of Indonesia

- Pura Parahyangan Agung Jagatkarta

- Sundanese people

- List of monarchs of Java